Prominent scholars of political behavior concede that retrospective, accountability-based voting informs electoral decisions (Reference DownsDowns 1957; Reference KeyKey 1966; Reference FiorinaFiorina 1981; Reference AndersonAnderson 2007; Reference Healy and MalhotraHealy and Malhotra 2013). However, recent studies of the electoral effects of indiscriminate events relating to the weather (Reference Gasper and ReevesGasper and Reeves 2011; Reference Sinclair, Hall and AlvarezSinclair, Hall, and Alvarez 2011; Reference Cole, Healy and WerkerCole, Healy, and Werker 2012; Reference Fuchs and Rodriguez-ChamussyFuchs and Rodriguez-Chamussy 2014; Reference Fair, Kuhn, Malhotra and ShapiroFair et al. 2017), shark attacks (Reference Achen and BartelsAchen and Bartels 2004a), and sporting events (Reference Healy, Malhotra and MoHealy, Malhotra, and Mo 2010; Reference MillerMiller 2013) have called into question the assumption of rationality often presumed to accompany retrospective voting. Collectively, the findings of these studies suggest that, beyond rewarding or punishing incumbent politicians for outcomes or performance within their control (in accordance with conventional retrospective voting theories), voters sanction politicians for haphazard, apolitical events with adverse public consequences. Is this practice universal? Under certain circumstances, do voters leverage alternative electoral mechanisms? As Sinclair, Hall, and Alvarez (Reference Sinclair, Hall and Alvarez2011) suggest, we know little about alternative implications of electoral behavior in the face of haphazard, apolitical events.

This article evaluates the operation of a competing rational prospective theory of voting through a study of the politics of the Zika virus in Brazil. Specifically, we consider whether the coincidence of Brazil’s 2015–2016 Zika epidemic and the unanticipated emergence of pressing challenges to infant health—an issue often perceived to be a “women’s issue”—influenced voting behavior in ways other than through the incumbent vote share. More pointedly, we consider whether exposure to the Zika virus affected voters’ political support for female mayoral candidates in local Brazilian elections. Through studying the politics of the Zika virus, we shed light not only on the utility of rational prospective voting but also on the ill-understood circumstances that motivate Latin Americans to apply gender stereotypes in their assessments of political leaders (Reference SetzlerSetzler 2019).

The first case of the mosquito-borne Zika virus in Brazil was documented in May of 2015. By November of that year, the number of reported cases of the virus burgeoned, and the Brazilian government declared a national emergency. The Zika outbreak continued unabated in the following year, during which period 170,535 cases of Zika were reported (BBC 2017). It was not until the spring of 2017 that the national emergency terminated.

The Zika epidemic was especially alarming to both the Brazilian government and the public alike due to its strong link to microcephaly, a birth defect characterized by abnormalities in the size of infants’ heads. The Zika virus and accompanying crisis in infant health primed issues that female politicians are perceived to be especially adept at addressing in the months leading up to the 2016 local elections in Brazil (Reference Alexander and AndersenAlexander and Andersen 1993; Reference Huddy and TerkildsenHuddy and Terkildsen 1993). We leverage the quasi-random experiment afforded by the indiscriminate outbreak of the 2015–2016 Zika epidemic to estimate the effect of the virus (resulting in a primed “women’s issue”) on political support for female candidates in the 2016 Brazilian local elections.

Our primary analysis is a difference-in-difference analysis that compares female mayoral candidates’ vote shares in the 2012 and 2016 Brazilian municipal elections across municipalities with varying levels of exposure to the Zika virus. We find that municipalities with more exposure to the Zika virus witnessed a statistically significantly greater increase in the female vote share from 2012 to 2016 than municipalities with less exposure to the Zika virus. Specifically, we learn that if the number of cases of Zika per 100,000 residents increases by 10 percent in the two months prior to the 2016 mayoral election, then the vote share for female mayoral candidates is predicted to increase by 0.579 percent. The effect is larger if we restrict our sample to consider solely cases of Zika among pregnant women. Although the magnitude of our results is small and unlikely to change electoral outcomes, in light of the impeachment of Brazil’s first female president and the anti-women backlash surrounding her removal from office (Reference Romero and KaiserRomero and Kaiser 2016), that we observe any effect of exposure to the Zika virus is indicative of the electoral salience of the priming of “women’s issues” in advance of electoral contests.

Where Politics and Gender Collide: A Review

Retrospective voting and beyond

Scholars have long sought to understand the many factors that influence voting behavior and, through their research findings, have largely conceded that theories of retrospective voting explain voting behavior in a multitude of contexts (Reference DownsDowns 1957; Reference KeyKey 1966; Reference FiorinaFiorina 1981; Reference AndersonAnderson 2007; Reference Healy and MalhotraHealy and Malhotra 2013).Footnote 1 Theories of retrospective voting posit that voters’ electoral decisions are informed by their evaluations of incumbent performance. Specifically, positive evaluations of incumbent performance lead voters to reward incumbent politicians or parties, and negative evaluations of incumbent performance lead voters to punish incumbent politicians or parties. Numerous studies provide compelling evidence in support of this theory of retrospective voting, especially in subsets of the literature assessing economic voting.

Newer scholarship extends conventional research on retrospective voting to consider its leverage in explaining voting behavior in the aftermath of indiscriminate, apolitical events relating to the weather (e.g., Reference Gasper and ReevesGasper and Reeves 2011; Reference Sinclair, Hall and AlvarezSinclair, Hall, and Alvarez 2011; Reference Cole, Healy and WerkerCole, Healy, and Werker 2012; Reference Fuchs and Rodriguez-ChamussyFuchs and Rodriguez-Chamussy 2014; Reference Fair, Kuhn, Malhotra and ShapiroFair et al. 2017), shark attacks (Reference Achen and BartelsAchen and Bartels 2004a), and sporting events (Reference Healy, Malhotra and MoHealy, Malhotra, and Mo 2010; Reference MillerMiller 2013). As previously documented, many of these studies largely confirm the continued operation of retrospective voting in the form of voters punishing incumbent politicians for the uncontrollable, adverse effects of floods, animal attacks, and painful athletic defeats. Such observations have led many to deduce that voters fail to exhibit rational behavior at the polls.

This article studies an epidemic comparable in nature to events traditionally studied in this part of the retrospective voting literature with the intention of probing the often-made assumption of voter irrationality. Specifically, it reevaluates the literature-informed expectation that voters behave irrationally as a consequence of haphazard frustration with apolitical calamities. It considers whether, under certain circumstances, voters practice restraint in sanctioning elected officials for circumstances beyond their control. This articles asks whether such indiscriminate events can, instead of activating retrospective voting and indiscriminate sanctioning of the incumbent, induce voters to practice rational prospective voting.

Rational prospective voting, contrary to retrospective voting, affirms that voters make levelheaded electoral decisions on the basis of how they anticipate a candidate or party to perform in the future. We assess whether, in the face of hardship stemming from a quasi-random epidemic, voters renounce haphazard, retrospective punishment of incumbents in favor of making rational decisions arrived at through the sensible activation of prospective voting. The literature-informed, gendered nature of the adverse effects to infant health stemming from the Zika epidemic in Brazil demands that we assess the activation of prospective voting informed by heuristics on gender stereotypes. In what follows, we provide a brief overview of the knowledge accumulated on political gender stereotypes in an effort to justify our focus on this particular heuristic.

Gender stereotypes: Perceptions and realities

In recent decades, a sizable literature on gender stereotypes relating to politics—chiefly in the context of the developed world—has emerged. Gender stereotypes relating to politics primarily concern personality traits, ideological affinities, and issue competencies. With respect to personality traits, female politicians are perceived to be more empathetic, compassionate, helpful, and consensus building and less corrupt than their male counterparts (Reference Alexander and AndersenAlexander and Andersen 1993; Reference Huddy and TerkildsenHuddy and Terkildsen 1993; Reference Morgan, Carlin, Singer and ZechmeisterMorgan 2015; Reference Funk, Hinojosa and PiscopoFunk, Hinojosa, and Piscopo 2019). Female politicians, in comparison with their male counterparts, are also more likely to be thought of as political outsiders (Reference Funk, Hinojosa and PiscopoFunk, Hinojosa, and Piscopo 2019). Male politicians, by contrast, are considered more assertive, dominant, and ambitious (Reference Eagly and KarauEagly and Karau 2002; Reference DolanDolan 2010; Reference BauerBauer 2015).

In terms of ideological affinities, female politicians are considered more liberal than male politicians (Reference Huddy and TerkildsenHuddy and Terkildsen 1993; Reference McDermottMcDermott 1997; Reference Herrnson, Celeste Lay and StokesHerrnson, Lay, and Stokes 2003; Reference Lloren, Rosset and WüestLloren, Rosset, and Wüest 2015). Although much of the empirical support underlying this connection stems from studies of developed countries, Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson (Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2009) and Morgan and Buice (Reference Morgan and Buice2013) identify an intricate relationship between the Latin American Left and women’s movements, feminist policies, and support for female political leaders. Their scholarship serves, in part, to corroborate the overarching stereotype derived from observations of the developed world.

Finally, regarding issue competencies, male politicians, are perceived as especially proficient policy makers in the areas of the economy, agriculture, employment, fiscal affairs, crime, and security (Reference LawlessLawless 2004; Reference Herrnson, Celeste Lay and StokesHerrnson, Lay, and Stokes 2003). Female politicians, by contrast, are generally perceived as especially adept policy makers in education, health, and other issues relating to “children and family” (Reference LeeperLeeper 1991; Reference Alexander and AndersenAlexander and Anderson 1993; Reference Huddy and TerkildsenHuddy and Terkildsen 1993; Reference Herrnson, Celeste Lay and StokesHerrnson, Lay, and Stokes 2003). The scholarly literature finds the connection between female representatives and issue spaces pertaining to education, health, and “children and family” to be universal. Research conducted on the Latin American region substantiates this claim.

According to Morgan (Reference Morgan, Carlin, Singer and Zechmeister2015), in Latin America, the interconnectedness of female politicians and family emphasis is especially pronounced. In her seminal book, Chaney (Reference Chaney1979, 21) argues that female politicians in the region view themselves as “supermadre[s], tending the needs of [their] bigger family in the larger casa of the municipality or even the nation.” Schwindt-Bayer (Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006) finds that although female legislators’ perceptions of their roles as politicians have evolved since the time of Chaney’s (Reference Chaney1979) writing, female legislators continue to place higher priority on “women’s issues” and children and family concerns than do their male legislative counterparts.

Gender stereotypes in each of the aforementioned areas may be formed on the basis of or reinforced by cross-gender disparities in legislation, bill introduction, or general behavior in campaigns and in the legislature (Reference Herrnson, Celeste Lay and StokesHerrnson, Lay, and Stokes 2003; Reference Chattopadhyay and DufloChattopadhyay and Duflo 2004; Reference Franceschet and PiscopoFranceschet and Piscopo 2008; Reference Schwindt-BayerSchwindt-Bayer 2010; Reference Lloren, Rosset and WüestLloren, Rosset, and Wüest 2015; Reference Hinojosa, Carle and WoodallHinojosa et al. 2018).Footnote 2 In the Latin American context, specifically, Franceschet and Piscopo (Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008) find that women are gendering the legislative agenda, and Schwindt-Bayer (Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010) claims that women provide substantive representation to other women as a function of their emphasis on women’s issues.

Especially pertinent to our research is Brollo and Troiano’s (Reference Brollo and Troiano2016) finding that, in Brazil, the election of female mayors results in better congenital health outcomes for women than the election of male mayors. In an effort to learn about the effects of the gender of elected officials, Brollo and Troiano (Reference Brollo and Troiano2016) exploit a quasi-experiment afforded by close election results to overcome endogeneity challenges relating to gender. They find that when female candidates win local elections, there is an increase in the share of pregnant women attending at least one prenatal care visit and a decrease in the share of women giving birth prematurely. Brollo and Troiano (Reference Brollo and Troiano2016) both demonstrate the utility of quasi-experimental research designs in uncovering unprecedented insights on gender politics and provide a compelling reason for voters to logically anticipate an intimate connection between the gender of elected officials and issues prioritized in office.

Despite the accumulation of literature attempting to identify perceived gender personality traits, ideological affinities, and issue competencies and to compare attitudinal and behavioral differences across male and female lawmakers, less is known about whether and the conditions under which gender stereotypes inform voters’ political behaviors and electoral choices (Reference LawlessLawless 2004; Reference DolanDolan 2010, Reference Dolan2014; Reference HayesHayes 2011; Reference Morgan and BuiceMorgan and Buice 2013; Reference BauerBauer 2015; Reference SetzlerSetzler 2019). Some scholars have attempted to fill this void with studies assessing the conditions under which political parties or voters activate gender stereotypes relating to personality characteristics. Funk, Hinojosa, and Piscopo (Reference Funk, Hinojosa and Piscopo2019, Reference Funk, Hinojosa and Piscopo2017) find that political parties are more likely to nominate women as public political trust in institutions falls because women are considered both political outsiders and less corrupt and more honest than men are. However, it is unclear whether similar behaviors emerge in political contexts afflicted by unforeseen natural disasters and epidemics. The standard belief is that female candidates are more successful when they capitalize on “gender issue ownership,” meaning that they run “as women” and emphasize “women’s issues” (Reference Herrnson, Celeste Lay and StokesHerrnson, Lay, and Stokes 2003). Whether this belief holds in light of unforeseen natural disasters and epidemics (and if it does, whether it resonates with voters and shapes electoral decisions) remains unknown.

From Zika to Electoral Support for Women: A Sequential Logic

Our research assesses whether exposure to the plausibly indiscriminate Zika virus encourages rational prospective voting, activates the use of gender stereotype-based heuristics, and results in increased electoral support for female candidates. In an effort to assess these relationships, we investigate the sequential logic and mechanism as outlined here:

Electoral season exposure to Zika → Learning of adverse implications of virus for infant health → Considerations about candidates’ competencies → Increased support for female candidates

First, a subset of Brazilian voters is exposed to the Zika virus during an electoral season. Second, voters rationally seek out information about the virus and its adverse implications. Third, upon learning about the detrimental implications of the virus for infant health, voters consciously or subconsciously activate heuristics to help them understand which types of political candidates are most adept policy makers in the areas of infant health. Finally, using rational prospective voting informed by gender-stereotype-based heuristics, voters cast their ballots in favor of female mayoral candidates. In what follows, we provide evidence of these four steps.

Electoral season exposure to Zika

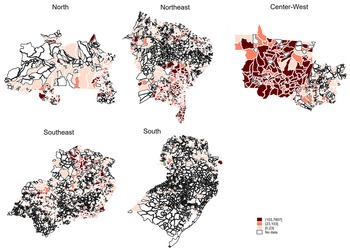

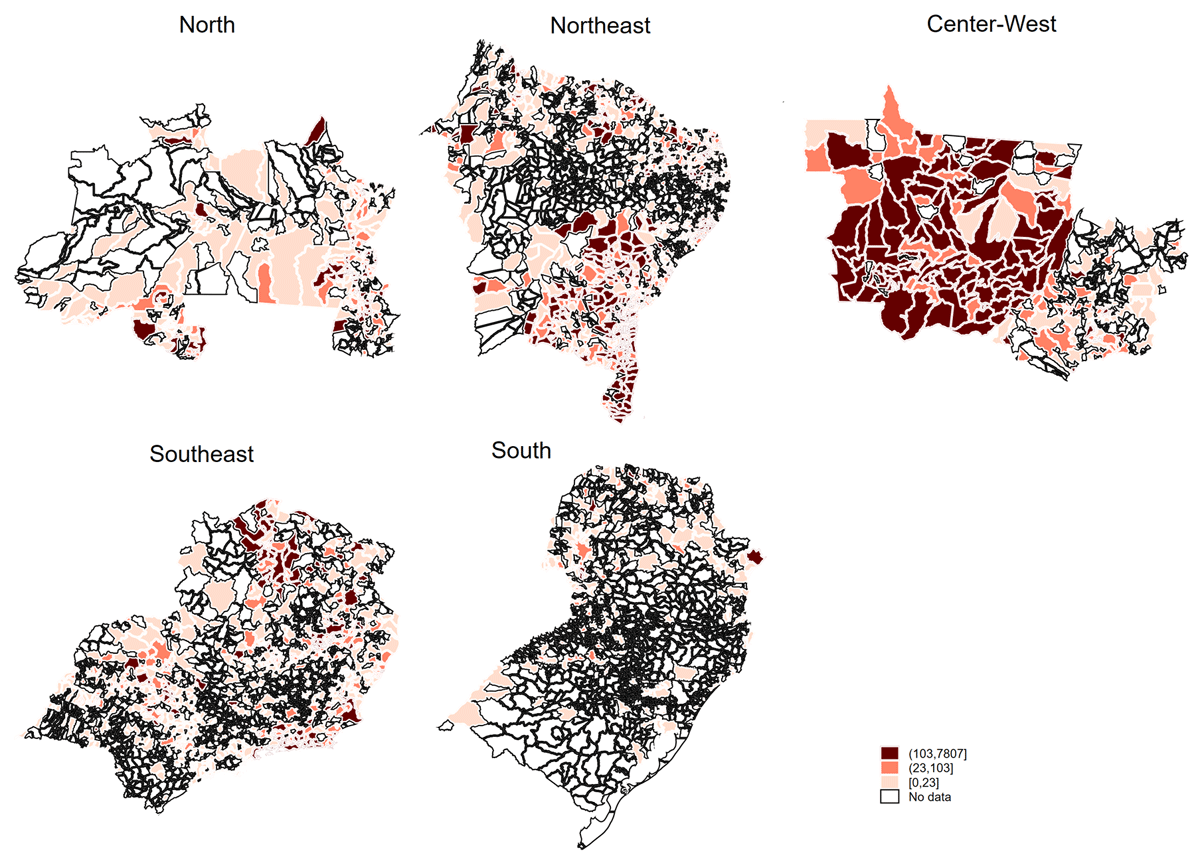

Since its most recent democratic transition, Brazil has held regularly scheduled local, state, and national elections. Local contests elect mayors and municipal representatives, and state and national contests elect presidents, governors, senators, and state and federal representatives. Local, state, and national elections are held every four years, but local contests are separated from state and national elections by two years. Brazil held local elections in 2016, a year dominated by a Zika epidemic–induced national emergency and immense public concern with the virus. Although outbreaks of the Zika virus were primarily concentrated in the Northeast and Center-West, the epidemic reached all of the country’s regions. Figure 1 depicts the spatial distribution of the reported total number of cases of the Zika virus in municipalities in each of Brazil’s five regions.

Figure 1 Cases of Zika per 100,000 people in 2016 by Brazilian region. Municipalities are distinguished by quartiles associated with the number of reported cases of the Zika virus in 2016. The darker the shading, the higher the number of reported cases of Zika. Municipalities shaded in white had no reported cases.

In total, 170,535 Zika cases were reported in 2016 (BBC 2017) and by April 30, 2016, 1,912 cases of microcephaly—a devastating condition linked with the Zika virus and marked by abnormalities in infants’ head size and brain development—were reported. Victims of microcephaly are understood to experience seizures, developmental delays, intellectual disabilities, difficulties with movement and feeding, as well as hearing loss and vision problems. These injurious effects cripple the lives of babies with microcephaly and may prove life threatening.Footnote 3 The virus-generated outbreak of microcephaly attracted the widespread attention of the Brazilian public and compelled Brazilians to rationally seek out information about the unfamiliar epidemic.

Learning of adverse implications for infant health

Figure 2 shows 2015 and 2016 Google searches from Brazil on the Zika virus as well as on two other infectious diseases transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito (the mosquito that transmits the Zika virus), Chikungunya and Dengue. This figure indicates that, prior to the first reported case of Zika in Brazil in May 2015, there were virtually no internet searches for the Zika virus in the country. The number of Zika searches initially peaked in November 2015, the month in which the Brazilian government declared a national emergency. In the “mosquito season” summer months of the following year, searches on Zika reached unprecedented levels. In early 2016, searches on the Zika virus outnumbered those on Chikungunya. Although searches on Dengue outnumbered searches on Zika in raw number, in terms of the ratio of searches to reported cases, the public did significantly more research on the Zika virus. In the first four months of 2016, the number of reported cases of Dengue in Brazil was approximately seven times greater than the number of reported cases of Zika (BBC 2017; Reference HerrimanHerriman 2016). The normalized scores of searches for Dengue in the same period, by contrast, was less than double the normalized scores of searches for Zika. We interpret this as a strong signal that the public sought out information about the Zika virus. The ubiquity of information available connecting the virus to microcephaly permits us to make the logical inference that Zika-informed Brazilian voters connected the virus with adverse implications for infant health in advance of the 2016 elections.Footnote 4

Figure 2 Google searches for Zika, Chikungunya, and Dengue. Normalized scores of search intensity; 100 indicates peak intensity for given search terms.

The Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) provides us with the resources to confirm that exposure to and rationally conducted research about the virus instilled in Brazilian voters the intimate connection between the virus and risks to infant health.Footnote 5 We use pertinent data from the 2017 LAPOP survey wave to assess whether survey respondents with personal exposure to Zika (i.e., respondents who either were diagnosed themselves or had someone close to them diagnosed with the virus) were more likely to perceive Zika as a serious threat to public health.

To do this, we implement a logistic regression analysis to estimate the effect of exposure to Zika on the probability of a respondent considering Zika to be a serious or very serious threat to health.Footnote 6 The results depicted in Table 1 confirm that exposure to Zika increases concern with the virus.

Table 1 Effect of exposure to Zika on concern with the virus.

Note: This regression controls for gender and age.

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1.

Our results suggest that voters exposed to Zika are 1.33 times more likely to consider Zika to be a serious threat to health in Brazil than their counterparts without exposure to the virus. This outcome requires Zika-exposed voters to have responded rationally to the emerging epidemic and to have judiciously sought out and acquired information about the virus. Exposure to, knowledge about, and concern with the virus plausibly led voters to factor the virus into their 2016 political decision-making calculations.

Considerations of candidates’ competencies

Despite the overlap between the Zika epidemic and Brazil’s 2016 electoral season, few Brazilian mayoral candidates discussed the issue in their campaigns (O Globo 2016).Footnote 7 This silence is especially puzzling given that Brazilian municipalities are partially responsible for controlling outbreaks of the virus and that mayors are the principal actors entrusted with legal, budgetary, and administrative matters within their jurisdictions (Reference WamplerWampler 2004).Footnote 8 Campaign silence on the issue meant that voters concerned with the virus were left to their own devices to discern which candidates would best address pressing challenges to infant health generated by the virus.

In an environment with limited information about candidates’ stances on both the virus and the appropriate methods of response, a large body of extant research on voter behavior suggests that Brazilian voters likely would have activated heuristics to help them make informed decisions.Footnote 9 More concretely, the gendered nature of the Zika-primed issues suggests that voters likely would have considered gender stereotypes relating to issue competencies. As described previously, female politicians are typically perceived as more adept policy makers in areas relating to infant health and family matters than their male counterparts are (Reference LeeperLeeper 1991; Reference Alexander and AndersenAlexander and Anderson 1993; Reference Huddy and TerkildsenHuddy and Terkildsen 1993; Reference Herrnson, Celeste Lay and StokesHerrnson, Lay, and Stokes 2003; Reference Brollo and TroianoBrollo and Troiano 2016). Insofar as this global stereotype extends to Brazil in light of the Zika virus, Brazilian voters would plausibly have come to the conclusion that female mayoral candidates were better equipped than their male counterparts to respond to the virus-imposed challenges to infant health.Footnote 10 In the section that follows, we assess the implication of this and the expected result of rational prospective voting in light of an indiscriminate epidemic.

Greater support for female mayoral candidates

In an effort to assess whether Brazilian voters practiced rational prospective voting in response to the Zika epidemic, we estimate the effect of exposure to the virus on support for female mayoral candidates. We focus on mayoral elections because Brazilian mayors are charged with developing and overseeing policies to control and respond to the outbreak of Zika. If Brazilian voters did, in fact, practice rational prospective voting, voters in Zika-prone areas will have voted in favor of female candidates at higher rates than voters residing in less Zika-prone areas.

To supplement our primary analysis, we also conduct placebo tests to capture the influence of potential endogenous factors related to the number of vector-borne mosquitos in Brazilian municipalities (e.g., underdevelopment, poor sanitation quality, climate). These tests allow us to assess whether the relationship between Zika-prone municipalities and support for female candidates exists through a channel other than that advanced in this article. Our placebo tests consider Chikungunya and Dengue. Chikungunya and Dengue are diseases transmitted by the same mosquito as that transmitting Zika (Aedes aegypti) but without adverse implications for pregnancy and infant health. If our logic holds, exposure to these viruses should not affect support for female politicians. To reiterate, we posit that exposure to the Zika virus will increase support for female candidates through rational prospective voting achieved through the activation of gender stereotype-based heuristics. Our placebo tests test the robustness of this argument.

To test our hypotheses, we collected municipality-level monthly data reports of Zika, Chikungunya, and Dengue cases for 2016 from the information technology department of the Brazilian Unified Health System (DATASUS) and data on the gendered distribution of the vote share from the 2012 and 2016 Brazilian mayoral elections from the Superior Electoral Court.Footnote 11 This data permits us to study the relationship between exposure to the Zika virus and the female vote share and to confirm that confounding variables related to the transmitting Aedes aegypti mosquito do not manufacture a spurious relationship. To assess our relationship of primary interest between exposure to the Zika virus and the female vote share, we implement difference-in-difference analyses with a continuous treatment variable following Acemoglu, Autor, and Lyle’s (Reference Acemoglu, Autor and Lyle2004) example.

Difference-in-difference analyses are valuable for the enterprise of assessing whether and the conditions under which exposure to an indiscriminate epidemic with gender-based issue implications influences the gendered vote share given that they control for the possibility of differences in baseline preferences regarding candidate gender.Footnote 12 Although to our knowledge gender disparities in baseline preferences have not been investigated in the Brazilian context, the revelation of such preferences in alternative contexts renders it necessary to account for the possibility in our analysis (Reference SanbonmatsuSanbonmatsu 2002; Reference BauerBauer 2015).

Specifically, we estimate variants of the following difference-in-difference model for each of the twelve months in 2016:

where VoteSharemt represents the vote share for female mayoral candidates in municipality m and election year t (2012 or 2016), given that municipality m had female mayoral candidates in both election years and had at least one Zika case reported in the 2016 month corresponding with the model.Footnote 13 Postt is a dummy variable equal to 1 when t = 2016 and 0 otherwise, and log(Zikam) is the logarithm of the number of reported cases of Zika per 100,000 residents in municipality m in the 2016 month corresponding with the model. Vector Xmt includes population, gross domestic product per capita, the vote share for female municipal council candidates, and municipal ideology as control variables.Footnote 14 Λm represents municipal fixed effects. Finally, ∈mt is the error term. The coefficient β 2 is the primary parameter of interest. It represents the effect of the Zika virus on the vote share for female mayoral candidates. We estimate similar models albeit with log(Chikungunyam) and log(Denguem) substituted for log(Zikam) to conduct our placebo tests.

Figure 3 contains the results of our primary difference-in-difference analyses. Our results suggest that the relationship between Zika outbreaks in the months leading up to the 2016 Brazilian mayoral elections and support for female mayoral candidates is positive and statistically significant. If the number of cases of Zika per 100,000 residents increases by 10 percent in August and September combined, then the vote share for female mayoral candidates is predicted to increase by 0.579 percent (Appendix Table A2).Footnote 15 By contrast, cases of Zika reported both earlier in the year and after Election Day (October 2) do not influence support for female mayoral candidates. These results confirm the utility of rational prospective voting in this Brazilian electoral climate. Further supporting this evidence is the fact that we do not find any significant effects of reported cases of Chikungunya and Dengue on the share of the vote cast for female mayoral candidates. The results of our placebo tests permit us to rule out the possibility that confounding variables relating to the transmitting Aedes aegypti mosquitos drive our primary results, thus substantiating the logic advanced in this article. Robustness checks further promote our argument.

Figure 3 Impact of cases of Zika, Chikungunya, and Dengue on support for female mayoral candidates. Vertical black lines represent 95 percent confidence intervals.

Robustness Checks, Falsification Tests, and Alternative Explanations

In an effort to provide additional evidence supporting our argument that exposure to the Zika virus activates rational prospective voting, we re-estimate our primary models with a sample restricted to cases of Zika among pregnant women reported in August and September combined. If our anticipated mechanism—that Brazilians exposed to the virus vote based on the perception that Zika is a “women’s issue” due to its link to infant congenital disabilities—is correct, then we should observe larger effects of exposure to Zika on the female vote share in municipalities with high incidence of the virus among pregnant women. We also should not observe any relationship between exposure to Chikungunya and Dengue and the female vote share.

Table 2 confirms our expectations. Column one suggests that the relationship between public exposure to the Zika virus and support for female mayoral candidates is positive and statistically significant when the analysis is restricted to consider solely municipalities with infected pregnant women. Additionally, it communicates that the effect of reported cases of Zika on the electoral support for female mayoral candidates is larger in magnitude when the analysis is restricted to consider solely municipalities with infected pregnant women (as compared to all municipalities with reported cases). If the number of reported cases of pregnant women diagnosed with Zika per 100,000 residents increases by 10 percent, then the vote share for female mayoral candidates is predicted to increase by 0.95 percent. By contrast, reported cases of Chikungunya or Dengue among pregnant women do not influence the female vote share.Footnote 16 These findings provide additional evidence in favor of rational prospective voting in response to an indiscriminate epidemic.

Table 2 Effect of public exposure to Zika, Chikungunya, and Dengue on share of the vote for female mayoral candidates restricted to municipalities with infected pregnant women.

Note: Regressions consider number of cases of each disease per 100,000 residents in August and September combined.

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1.

The main identification assumption of difference-in-differences analyses is the anticipated presence of parallel trends in outcomes in the absence of treatment. Although our analysis in Figure 3 reassures this requirement—as prior to July, Zika-prone areas did not show significantly more support for female candidates than less affected areas—we provide additional evidence of parallel trends by computing the percent of votes received by female candidates in 2008 and, subsequently, measuring whether or not disease outbreaks in 2016 predict the difference in the female vote share between 2008 and 2012. Our results indicate that municipalities with Zika outbreaks in 2016 did not exhibit trends of increasing female political success prior to 2016. Put differently, our analysis suggests that prior to the intervention of the virus, Zika-exposed and non-Zika-exposed municipalities exhibited parallel political trends. Table 3 contains our results.Footnote 17

Table 3 Effect of exposure to Zika, Chikungunya, and Dengue on share of the vote for female mayoral candidates, falsification test (2008 vs. 2012).

Note: Regressions consider number of cases of each disease per 100,000 residents August and September combined.

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1.

In our final effort to introduce evidence of rational prospective voting in light of the Zika epidemic, we dispel alternative explanations that could underlie our results. Our main argument is that, in the face of the Zika epidemic, Brazilian voters used rational prospective voting. We posit that rational prospective voting led Brazilian voters to utilize gender stereotypes relating to the “women’s issue” of congenital health to make electoral decisions and to provide increasing support to female political candidates (Reference Brollo and TroianoBrollo and Troiano 2016). Our theoretical framework differs from that highlighted in a previously reviewed, robust literature that discerns retrospective voting behaviors in light of indiscriminate events relating to the weather (e.g., Reference Cole, Healy and WerkerCole, Healy, and Werker 2012; Reference Fuchs and Rodriguez-ChamussyFuchs and Rodriguez-Chamussy 2014; Reference Gasper and ReevesGasper and Reeves 2011; Reference Fair, Kuhn, Malhotra and ShapiroFair et al. 2017), shark attacks (Reference Achen and BartelsAchen and Bartels 2004a), or sporting events (Reference Healy, Malhotra and MoHealy, Malhotra, and Mo 2010; Reference MillerMiller 2013). Throughout this article, we have dismissed the possibility that exposure to the Zika virus activated retrospective voting. In this section, we test this alternative theoretical supposition directly.

The rich literature on retrospective voting in light of haphazard events would predict that aggrieved voters exposed to the Zika virus would sanction incumbent politicians. If incumbents in municipalities with greater exposure to the Zika virus were disproportionately male, then our findings might simply reflect voters’ haphazard punishment of male candidates. In what follows, we demonstrate that areas with greater exposure to the Zika virus were not more likely to have had male incumbents. In doing this, we confirm the unlikelihood of voters irrationally punishing male incumbents out of frustration relating to the Zika virus instead of rewarding female policy makers with perceived competencies in the area of infant health. Our finding goes against the conventional wisdom of retrospective voting in light of indiscriminate circumstances.

Retrospective voting could also operate and underlie our observed primary results in more dubious ways. If political parties—anticipating conventional retrospective voting and the accompanying punishment of male incumbent politicians—proactively nominated or provided additional financial support to female candidates, these actions, too, could serve as signals of retrospective voting at work. We consider these two possibilities in turn.

A robust literature on strategic politics and political ambition suggests that potential candidates condition their decision to compete for office on their evaluated propensities of winning.Footnote 18 Numerous factors contribute to political candidates’ propensities for success. Among these, political-party nomination and backing are fundamental. Recent literature shows that, at least in the context of Latin America, political parties are increasingly likely to nominate female candidates when confronted with electoral environments that bode poorly for male candidates (e.g., environments characterized by widespread public distrust and pervasive corruption) (Reference Funk, Hinojosa and PiscopoFunk, Hinojosa, and Piscopo 2017, Reference Funk, Hinojosa and Piscopo2019). Insofar as the Zika virus fostered a similar environment, it is plausible that it altered political-party gatekeepers’ strategic calculations surrounding political nominations to the benefit of female candidates. On the basis of this logic, one might suspect that the Zika virus would, by way of political-party nominations, alter female candidates’ calculations to contest political office. However, in our forthcoming analysis, we show that this was not the case; women were not more likely to contest mayoral elections in municipalities with more reported cases of the Zika virus.

In another effort to consider more dubious retrospective voting mechanisms, we consider the probable reality that campaign funding discrepancies across candidates disparately affected by the Zika virus underlie our observed results. That money drives politics is common knowledge. This relationship is especially pronounced in democratic societies with comparatively expensive elections. In Brazil—where elections are among the most expensive in the world (Reference MainwaringMainwaring 1999; Reference SamuelsSamuels 2001)—Samuels (Reference Samuels2001) finds that candidates with more financial resources do better than candidates with fewer financial resources. It is plausible that the Zika-permeated climate surrounding the 2016 elections in Brazil impacted political parties’ strategic calculations not only on who to nominate but also on how to optimally distribute financial resources. Along these lines, it is possible that political parties made resources disparately available to female candidates on the basis of their municipalities’ levels of exposure to the Zika virus and, by doing so, differentially impacted female candidates’ propensities of electoral success.

However, forthcoming analyses designed to probe these alternative explanations confirm that women running for mayor in municipalities with more reported cases of Zika did not have disproportionately more financial resources than their counterparts in municipalities with less reported cases of Zika. If well-funded female candidates were more likely to compete in municipalities with more cases of Zika because they perceived that these municipalities would offer them better opportunities to be elected, then our results would be biased upward; municipalities with higher incidences of Zika would also have wealthier female candidates who were more equipped to win elections. However, we show that the financial resources of female mayoral candidates, on average, were similar across municipalities with disparate levels of exposure to the Zika virus. This result further confirms that neither retrospective voting nor the anticipation of it underlies our observed results.

Aside from alternative explanations related to retrospective voting theories, it is plausible that our primary result of a positive relationship between exposure to the Zika virus and support for female candidates may be driven by increasing support for abortion and political parties with pro-abortion stances or by obscure virus-motivated electoral turnout patterns. In what follows, we document the logic underlying and the literature supporting each of these alternative explanations and foreshadow the minimal empirical support we find to back them.

We consider the possibility that instead of increasing support for female candidates as a function of rational prospective voting, Brazilian voters’ increased support for female candidates stemmed from a purposeful uptick in support for pro-abortion political parties (many of which also advocate for the increased political representation of women). Research finding that the Zika virus had a fertility-depressing effect (Reference Senters and SchneiderSenters and Schneider 2019) conjectures that the Zika epidemic also influenced support for abortion. Further supporting this presumption is research by Aiken et al. (Reference Aiken, Gomperts, Trussell, Worrell and Aiken2016) finding that, in light of the Zika virus, Latin Americans’ abortion requests to Women on Web skyrocketed and, at the height of the epidemic, Brazilians discussed the possibility of legalizing abortion for pregnant women diagnosed with the virus.Footnote 19 Rodrigo Janot, Brazil’s then attorney general, went so far as to initiate a bill in September 2016 to legalize abortion for pregnant women diagnosed with Zika (Veja 2016). If voters exposed to Zika were disproportionately likely to favor pro-abortion policies—as Cohen and Evans (Reference Cohen and Evans2018) found—and to support pro-abortion parties, and if women were disproportionately likely to belong to these parties, then our results would be overestimated.

However, our analyses show that exposure to Zika did not influence preferences for pro-abortion parties with which female candidates may have been more commonly affiliated. We demonstrate that exposure to Zika does not predict support for pro-abortion parties. This result suggests that voters privileged candidates capable of responding to existing problems to infant health over parties committed to inducing change that would mitigate similar future challenges.

Finally, we consider the possible operation of obscure virus-motivated turnout patterns. If voters with more exposure to Zika were more concerned about the virus, it is plausible that this concern may have mobilized them to turn out to vote and to support female candidates and that voters with less exposure to the virus were no more mobilized than usual. Insofar as exposure to Zika is a mobilizing force for nonregular voters in municipalities with more exposure to the virus, it could explain the observed relationship between the virus and the female vote share. However, we show that turnout is unaffected by exposure to Zika and, therefore, is unlikely to underlie our primary observed relationship. Given that voting is mandatory in Brazil, this finding was to be expected, but this confirmation provides additional support for our main argument.

We consider and dispel each of the aforementioned alternative explanations with similar difference-in-difference models to those used in our primary empirical analysis. The models used in this section are variants of Equation 1, albeit with dependent variables corresponding with our considered alternative explanations. The data associated with our dependent variables comes from the Superior Electoral Court and Duke University’s Democratic Accountability and Linkages Project.Footnote 20 Table 4 contains these results.

Table 4 Dispelling alternative explanations underlying the relationship between exposure to Zika and the vote share of female candidates.

Note: Regressions consider number of cases of Zika per 100,000 residents in August and September combined.

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1.

As Table 4 depicts, none of the introduced alternative explanations are supported. In Table 4, we show that incumbent mayors in Zika-prone areas were not more likely to be male. We also show that political parties in Zika-prone areas are neither more likely to support female candidates nor to financially invest more in them. These results dispel the possibility that retrospective voting underlies our result of a positive relationship between exposure to the Zika virus and support for female candidates. In Table 4, we show that pro-abortion parties did not receive significantly more support in Zika-prone areas. Finally, we show that turnout is unaffected by exposure to the virus. In sum, these results increase confidence in our supposition that gender stereotypes relating to issue competencies underlies our observed relationship between Zika exposure and the female vote share and that, in the face of the Zika virus, Brazilian voters utilized rational prospective voting.Footnote 21

Discussion and Conclusion

Recent political behavior scholarship has questioned often-made assumptions of voter rationality through studies of electoral behavior in light of haphazard, apolitical events. These studies’ findings deduce that grieving voters sanction incumbent politicians for events or outcomes largely outside of incumbent control. We revisited this finding to determine whether, instead of invoking irrational responses, such indiscriminate events can sometimes induce voters to practice rational prospective voting. We evaluated the operation of rational prospective voting through studying the politics of the Zika virus.

Specifically, we leveraged the quasi-random experiment afforded by the indiscriminate outbreak of the 2015–2016 Zika epidemic to estimate the effect of the virus and its primed salience of the “women’s issue” of infant health on political support for female candidates in the 2016 Brazilian local elections. With difference-in-difference analyses, we demonstrated that areas with higher incidences of Zika in the months immediately preceding the 2016 local elections witnessed greater increases in the female vote share in between the 2012 and 2016 elections than areas with lower incidences of the virus. We further confirmed the validity of our results by demonstrating the robustness of our results, the compelling satisfaction of regression assumptions, and the incredibility of alternative explanations.

Our results confirm that, in light of indiscriminate events with adverse consequences, voters do not always default to vote retrospectively and to sanction incumbent politicians. Instead, they suggest that, when confronted with pressing challenges outside of incumbent control, voters may vote both rationally and prospectively. To our knowledge, this finding is largely unprecedented, especially in the context of the developing world in which less mature voters are sometimes assumed to exhibit more erratic electoral behaviors. Moreover, it confirms that normative democratic electoral behaviors are not out of reach, even in developing contexts. Beyond elucidating the complex calculations underlying voting behavior, we shed light on the ill-understood circumstances that lead Latin Americans to apply gender stereotypes when assessing their political leaders (Reference SetzlerSetzler 2019) and, arguably more pointedly, the conditions favorable to female candidates’ electoral prospects. Increasing the political representation of women is understood to be an important requisite for mitigating pervasive gender inequalities and is, consequently, a global policy priority. Despite near-ubiquitous commitment to enhancing female political representation, progress on this front has remained slow (especially in the Latin American context; see Reference Basabe-SerranoBasabe-Serrano 2020). While gender electoral quotas, for example, have helped spur some advances in female representation (Reference WylieWylie 2018; Reference SacchetSacchet 2018), they have not proved be-all, end-all solutions to the challenge of female underrepresentation in politics (Reference HtunHtun 2002).

Insofar as the priming of “women’s issues” results in favorable electoral prospects for female politicians, political gender imbalances may be mitigated in the short run. If women elected in response to the (un)intended priming of “women’s issues” prove their capabilities once in office and incur additional public support as a result, the priming of “women’s issues” may instill increased political representation in the longer term.Footnote 22 Speaking to this, Speck (Reference Speck2018, 57) finds that “in the municipalities in which a female mayor was elected, the probability of having first-time female candidates in the next election is 1.8 times higher than in the last electoral contest.” If future research investigates and determines that women are proactive in their mandates to address the challenges that contributed to their election (e.g., female candidates elected in response to the emerging challenges associated with the Zika virus),Footnote 23 female candidates ought to claim ownership and continuously raise the salience of issues that voters perceive them to be especially adept at addressing. In sum, the Zika virus and accompanying priming of “women’s issues” serves as an important example of a circumstance with the potential to generate both short- and long-term yields for women’s political representation.

Although we have focused on evaluating the utility of rational prospective voting in the Brazilian context because of the opportunity to do so afforded to us by the quasi-random Zika outbreak, we believe that our results generalize beyond Brazil. We expect that voters might practice rational prospective voting to the benefit of political candidates with perceived competencies on primed issues more broadly. We anticipate this type of electoral behavior to be particularly prevalent in countries with institutions that, like Brazil’s, empower individual politicians vis-à-vis political parties and incentivize political candidates to cultivate the personal vote (e.g., open-list proportional representation systems). However, irrespective of adopted institutions, the widespread extrapolation of rational prospective voting hinges on the absence of conflicting primed issues (e.g., in the context of our project, the priming of “men’s issues” alongside of the priming of “women’s issues”). Future research should further probe the real-world, long-lasting implications of the Zika virus and leverage the recently emergent COVID-19 pandemic to test the generalizability of rational prospective voting.Footnote 24

Overall, this article probes and extends an already-saturated literature on political behavior. We discern that, even under arguably unlikely circumstances, voters eschew retrospective voting in favor of prospective voting and that haphazard, apolitical events can have important and desirable implications for electoral outcomes. As the buzz around elections takes on different forms in response to unpredictable epidemics, devastating natural disasters, and/or terrorist attacks, scholars should explore the political effects.

Additional File

The additional file for this article can be found as follows:

• Appendix. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.916.s1

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this paper are the authors’ alone and in no way represent the opinions, standards, or policy of the United States Air Force Academy or the United States government. PA#: USAFA-DF-2020-380.