Legislative studies are one of the key research areas of political scientists. The field is concerned with the heart of democratic governance: understanding and explaining parliaments and the actions of representatives. Parliaments’ records on various means of parliamentary communication such as written and oral requests, motions and reports constitute one of the main data sources for scholars. Based on texts, researchers address topics as diverse as representation and responsiveness, parliamentary agendas and parliamentary organization (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014; Bailer Reference Bailer2011; Bird Reference Bird2005; Celis Reference Celis2006; Elsässer et al. Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2017; Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Proksch and Slapin2013; Koß Reference Koß2015; Manow Reference Manow2013; Metz and Jäckle Reference Metz and Jäckle2016; Mügge et al. Reference Mügge, van der Pas and van de Wardt2019; Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2011). While providing numerous interesting insights into the functioning of democratic decision-making and democracy, scholars regularly need to narrow the scope of their work due to data restrictions: they can only study short time horizons, single types of text documents or a fixed policy area, because processing written parliamentary documents is resource intensive. In the absence of comprehensive data sets covering all written parliamentary communication in a country, political scientists get only a glimpse of the full picture. In this research note, we enrich researchers’ data sources by introducing a data set that includes records of all written communication that have been published by the German parliament.

Our data set contains the full official record of the Bundestag, covering the period between 1949 and 2017 and amounting to a total of 131,835 documents.Footnote 1 It includes requests, responses and briefings, reports, bills and decrees, as well as proposals submitted by groups of or individual legislators, party parliamentary groups, committees or the government. In addition to entailing the documents’ titles and full texts, our data set also provides document-related details, such as the date of submission in addition to the names of the authors. We thus provide scholars in the field with easy access to original texts and related metadata that can be analysed in both quantitative and qualitative terms and complement existing databases concerned with parliamentary speeches or roll-call voting behaviour. To date, no comparable collection of data exists for Germany or, to our best knowledge, any other parliamentary democracy. In compiling the complete written communication of the German federal legislature over a 70-year period, we therefore present the most comprehensive data set of its kind that will allow new ground to be broken for empirical political science research.

Our data opens the opportunity to study a whole set of innovative and timely research questions. The broad variety of document types enables scholars to consider how their study object varies with the nature of the written communication. We clarify how the data set can enhance the state of research in legislative studies through two brief example analyses. In the first example, we demonstrate how the data set contributes to the field of legislative career studies. We explore the role of support for minor interpellations and motions by individual members of parliament (MPs) for reaching committee chair positions. In the second example, we highlight this potential line of research for the field of women's representation by analysing the degree to which male and female legislators engage with issues related to children and childcare. We reveal how the gender gap in the share of related oral questions changes over seven decades.

Review of existing data on parliamentary activities

A growing number of longitudinal data sets are concerned with the activities in both national and supranational legislative bodies. The data can be divided into three different categories (see Figure 1): for one, researchers have gathered comprehensive information about legislators’ roll-call voting behaviour for a growing number of parliaments. These data enable legislative scholars to analyse MPs’ voting patterns, examining, for example, the German Bundestag between 1949 and 2013 (Sieberer et al. Reference Sieberer, Saalfeld, Ohmura, Bergmann and Bailer2018), the Dutch Second Chamber between 1945 and 2017 (Louwerse et al. Reference Louwerse, Otjes and van Vonno2017) or the European Parliament between 1979 and 2009 (Hix et al. Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2009). Second, there exist numerous data sets containing the minutes of plenary proceedings for democracies around the world. GermaParl, for instance, contains annotated full texts of the Bundestag plenary sessions’ protocols over six legislative periods (Blätte Reference Blätte2017). The most extensive collection of plenary protocols can be found in the ParlSpeech data set, which contains more than 6.3 million speeches held in the parliaments of nine different Western democracies between 1987 and 2019, as well as additional information concerning the speaker or the plenary agenda (Rauh and Schwalbach Reference Rauh and Schwalbach2020). Several other databases cover additional countries or different time spans, such as Portugal 1976–2019 (Almeida et al. Reference Almeida, Marques-Pita and Gonçalves-Sá2020) or Iceland 1911–2017 (Steingrímsson et al. Reference Steingrímsson, Helgadóttir, Rögnvaldsson, Barkarson, Guðnason and Calzolari2018). On the supranational level, the EuroParl data set contains speeches held in the European Parliament between 1996 and 2011 (Koehn Reference Koehn2005).

Figure 1. Different Types of Data on Parliamentary Activities

While the content of plenary debates and MPs’ voting behaviour have thus become increasingly relevant and accessible research objects, a third category of data stemming from legislative activities has attracted less attention: written communication as part of parliaments’ official record, including requests, reports or bills, for instance. However, these documents provide a rich and valuable source of information for political scientists and could shed light on diverse parliamentary activities such as legislative oversight or policymaking. Existing empirical analyses of written communication therefore inevitably remain limited: they usually focus on a single type of document and/or a very limited time span, examining only a snapshot of the complete variety and history of written communication in a given legislative body.

To some extent, this lack of data has been addressed by a growing number of web pages that provide full text access to parliamentary documents in PDF or XML format. Most prominently for the German case, the parliament itself publishes all official publications since 1949 as PDF documents at pdok.bundestag.de. While this tool allows to identify a subsample of documents through keywords searches, it does not provide standardized ways to download relevant documents or any type of background information on the matches. Addressing this shortcoming, additional web pages focus on single types of documents, such as Kleineanfragen.de on written requests (2013–2019) or offenegesetze.de on the full text of bills (1949–2019). While this enables researchers to limit their study objects to some relevant text formats in an easier manner, the time- and computation-intensive task to reformat the documents into information ready for analysis with standard statistical software remains up to the users.

Several researchers went to the effort of reformatting parts of the data – for example, presenting analyses of oral questions of MPs of immigrant origin between 1987 and 2009 (Wüst Reference Wüst2014) and all oral questions between 2002 and 2013 (Bailer and Ohmura Reference Bailer and Ohmura2018), federal legislation between 1976 and 2005 (Miller and Stecker Reference Miller and Stecker2008) or all motions between 1976 and 2002 (Manow and Burkhart Reference Manow and Burkhart2007). Still, only a small share of the overall information is accessible and even these limited data are dispersed over a broad variety of sources.

This lack of a comprehensive processed data set ready for text analysis is not unique to the German case. To name just a few examples, researchers studied the topics of bills submitted to the US Congress between 1994 and 2002 (Gerrity et al. Reference Gerrity, Osborn and Mendez2007) or the content of parliamentary questions in the UK House of Commons over a five-year period (Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2011) and the Second Chamber of the Netherlands over 20 years (Otjes and Louwerse Reference Otjes and Louwerse2018). However, there was no complete data set covering the full variety of written communication of a national parliament for even one complete legislative period – a blank space we fill for the German case.

A new data set on written parliamentary communication

Our data set (at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/7EJ1KI) contains all written communication published by the German Bundestag between 1949 and 2017 in a manner easily accessible to researchers applying text analysis. To develop it, we made use of the Bundestag website's open data repository (Bundestag 2018), where the parliamentary archive has made available all of the parliament's written communication during the first 18 legislative periods. Overall, this database covers 131,835 documents, which can be downloaded as XML files. These files contain not only the text of the respective document, but also a variety of metadata, which we retrieved using the statistical software R, and especially the R packages XML (Lang Reference Lang2019) and stringr (Wickham Reference Wickham2019). For each document, this allows us to include: (1) the full text; (2) information describing the document in detail (type of document, subject line, date of submission, running number (Drucksache), legislative period); and (3) author information (name(s), party/institutional affiliation(s)).

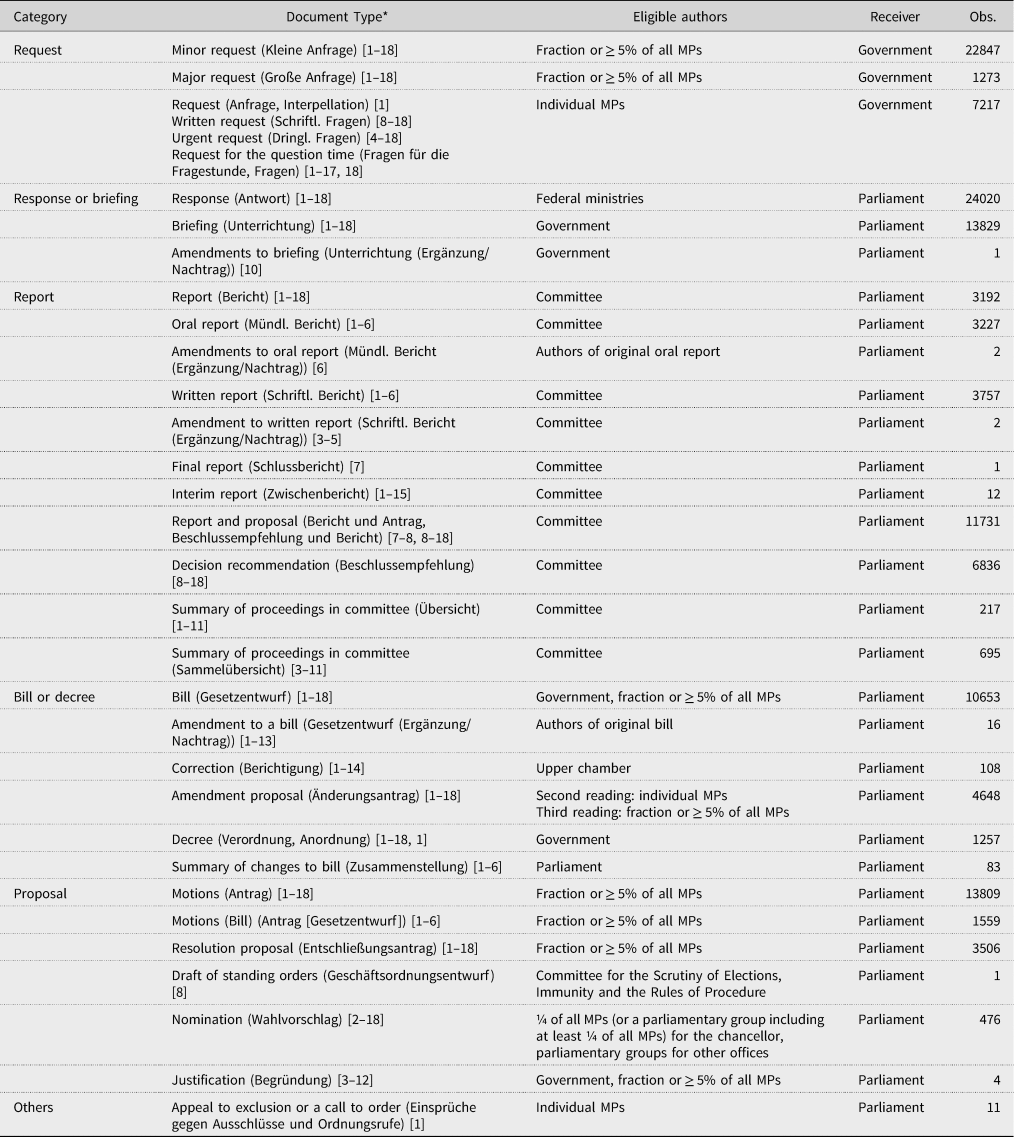

We identify six substantially different types of documents: requests, responses, reports, bills and decrees, motions, and others. They vary in the eligible authors, the intended receivers and the type of content they provide, making them a rich and valuable source of information. Details on every type of document are provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Types of Documents Included in the Data Set with Details

Note: *German original wording indicated in parentheses, electoral periods for which each type of document is available indicated in brackets.

The first type of document, requests, is submitted by members of parliament to the government. Individual MPs can file written and oral questions, groups of MPs and party parliamentary groups can also submit larger requests that might be put on the agenda of plenary debates. Second, responses or briefings contain information from the executive for the legislature either on request or on its own initiative. Furthermore, reports are summaries of discussions of bills or motions in the leading committees. Various types exist, including written and oral, final and interim reports. They might also contain additional legislative proposals or decision recommendations for the legislature. The fourth type, bills or decrees, contains any legislative initiative to be voted on by parliament. This includes laws and bylaws submitted by the government, parliamentary groups or more than 5% of all MPs, but also corrections to bills proposed by the upper chamber (Bundesrat). Other issues to be voted on are summarized under our fifth type as proposals. This category contains initiatives in which sections or groups of MPs ask the government to act on certain issues or revisions of current legislative drafts within the executive. In this category, we also include point-of-order proposals and nominations for the election of the chancellor, (vice-)presidents of parliament and clerks. Last, the documents include appeals to exclusion or a call to order summarized as ‘others’. Throughout all types of documents, the data set also includes a small number of amendments.

Figure 2 indicates the frequency of each document type in every year. It shows that, overall and on average, a positive time trend exists, meaning that the amount of written communication in parliament increased over time. The positive time trend also holds for most document types, albeit with considerably more variation. While the number of bills or decrees only increased slightly and stagnated from the 1970s, the number of requests and responses or briefings continues to grow steadily. Most of the fluctuation over time can be explained by the electoral cycle.

Figure 2. Frequency of Document Type per Year in the Data Set

Bearing in mind the needs future researchers might have when working with these data, we provide several add-ons. First, we suppose that many researchers will want to combine our data with additional information about representatives such as gender, party ideology, electoral safety or parliamentary posts. Comprehensive information on German legislators’ characteristics was recently published by Henning Bergmann et al. (Reference Bergmann, Bailer, Ohmura, Saalfeld and Sieberer2018) and – where appropriate – we provide an identifier that allows the two data sets to be merged. The combination of data including MPs’ names, but also their entry into parliament, enables users to merge our data with other sources of information about German MPs they might have. Further, if all written questions are summarized in a single document, scholars might want to make use of text fragments by single authors rather than overall published documents. We therefore provide a reshaped data set with text units per author as observations, separating requests where necessary. The data package thus provides researchers with two data sets ready for analysis.

Branches of research analysing written parliamentary communication

This data set covering all written communication in the German Bundestag contains a broad variety of study objects relevant to substantially diverse sets of research. Scholars might be interested in analysing topics as diverse as parliamentary agenda, parties (or parliamentary groups), individual MPs, committees or governments. For that purpose, one might extract simple frequencies of occurrences, topics, representative claims or sentiments from the records. In this section, we discuss how our data set can contribute to ongoing and new debates in various fields of literature such as representation, politics and gender, legislative careers and professionalization, or comparative agenda studies. We cluster our review of the literature along the three key research interests: parliaments, parties and representatives. While a complete review of each set of literature would go beyond the scope of this research note, the following brief overview aims to inform how the availability of data restricts research agendas and to inspire readers by showing how our comprehensive data set might allow them to address some of these topics.

Parliaments

The content, change and evolution of parliamentary agenda control takes centre-stage in a vast body of research in political science. To begin with, researchers aim to understand the evolution of the functioning of legislatures by investigating parliaments’ procedural reforms. Through analyses of governing parties’ reactions to obstructive behaviour by the opposition, scholars reveal centralization or delegation tendencies of agenda control and their origins (Koß Reference Koß2018). Furthermore, scholars ask if and how political parties use parliamentary questions strategically to increase issue salience rather than employing them as a means to bridge information asymmetry and monitor the government's actions (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Proksch and Slapin2013; Otjes and Louwerse Reference Otjes and Louwerse2018).Footnote 2 A number of studies focus on amendments made to bills throughout the legislative process in parliament to determine committees’ and interest groups’ influence on policymaking (Eising and Spohr Reference Eising and Spohr2017) or how the degree of cooperation between government and opposition hinges on the majority constellation in an upper chamber (Manow and Burkhart Reference Manow and Burkhart2007; Miller and Stecker Reference Miller and Stecker2008). Moreover, studies shed light on the internal structure and hierarchy within parliamentary groups in parliament by analysing co-authorship of parliamentary questions and interpellations (Metz and Jäckle Reference Metz and Jäckle2016). Lastly, scholarly work in this field examines sponsorship and co-sponsorship of bills to reveal under which circumstances MPs choose to table or support motions, and under which conditions the proposals are successful (Bratton and Rouse Reference Bratton and Rouse2011; Fowler Reference Fowler2006; Tam Cho and Fowler Reference Tam Cho and Fowler2010).

For research studying agendas and procedural reforms of parliaments, complete time-series data for a single country would enable scholars to illustrate the presence and change of observed patterns over time. Further, analysing various types of written communications for the same legislature might reveal to what extent our knowledge depends on the nature of the communication that researchers decide to study and whether well-established relationships change if different types of documents are taken into account. A comprehensive data set makes it possible to reveal the different strategies that governing and opposition parties or party parliamentary groups apply when enquiring through individual or group requests, asking the government to act through motions, or suggesting concrete legislation through bills and decrees.

Parties

Studies concerning parties’ policy positions increasingly rely on the written word. Originally starting with party manifestos (Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2019), scholarly work throughout the 2000s showed that analyses of parliamentary speeches also reveal parties’ ideological and policy positions (Laver et al. Reference Laver, Benoit and Garry2003; Lowe et al. Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011; Slapin and Proksch Reference Slapin and Proksch2008). To give just two brief examples of how researchers made use of this innovative approach: Sven-Oliver Proksch and Jonathan Slapin (Reference Proksch and Slapin2010) ask how national parties position themselves in the European Parliament, revealing that traditional left–right partisan divisions constitute the principal latent dimension of spoken conflict rather than European integration or nationality. Julian Bernauer and Thomas Bräuninger (Reference Bernauer and Bräuninger2009) study to what extent intra-party heterogeneity in policy positions persists and they find (albeit limited) support for diversity mirroring individuals’ fraction membership. Given that access to speech time in plenum is limited in most countries, studying further written communication by party parliamentary groups, groups of representatives and single legislators promises more nuanced insights into the policy positions of small parties and backbenchers.

A related set of research engages with the changing role and positions of political parties in the light of a ‘populist zeitgeist' (Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, Lange and van der Brug2014). Increasing numbers of studies investigate if there is a ‘contagion effect' of right-wing populism that causes mainstream parties to adopt populist positions or style of communication (Manucci and Weber Reference Manucci and Weber2017; Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, Lange and van der Brug2014). Our data set can help researchers interested in populism to answer these questions, moving the scope of analysis beyond political demands and statements made in election manifestos or political speeches. Scholars can use our data to assess whether a contagion effect can be found in parties’ legislative work, whether their parliamentary questions or draft bills become more populist programmatically or rhetorically over time and with the increasing success of the Alternative for Germany.

Representatives

Aiming to uncover the substance of MPs’ legislative action, researchers study the topics of or analyse representative claims in parliamentary requests, legislative drafts and speeches. One question that concerns a large and continually growing group of literature is the degree of responsiveness of parliamentary work or to what extent representatives aim to promote the policy demands of the people as a whole (see e.g. Bailer Reference Bailer2011; Elsässer et al. Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2017; Gilens Reference Gilens2005; Manow Reference Manow2013) or subgroups such as women, immigrants or ethnic minorities (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014; Bird Reference Bird2005; Celis Reference Celis2006; Mügge et al. Reference Mügge, van der Pas and van de Wardt2019; see e.g. Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2011; Wüst Reference Wüst2014). Many of these latter studies ask to what extent Anne Phillips's famous theory of the ‘politics of presence‘ (Reference Phillips1995) – which states that members of traditionally excluded groups will promote group interests – finds empirical support. Others draw attention to the role of context, questioning to what extent electoral incentives such as varying modes of election or composition of the electorate moderate the effect of group identities on legislative behaviour (Lončar Reference Lončar2016; Wallace Reference Wallace2014). Conceding that an investigation into only one type of document from a parliament's official record does not provide a satisfactory assessment of MPs’ legislative actions, many scholars dealing with the substantive representation of certain social groups call for further analyses resting on a broader database (Mügge et al. Reference Mügge, van der Pas and van de Wardt2019). This would enable students of representation to develop an integrated model of representatives’ parliamentary work in all its facets. Due to the longitudinal format, our data set will further allow researchers in the field to move beyond analyses of the status quo and ask to what extent representation changes as a consequence of factors such as the mediatization and personalization of politics.

A related set of studies follow the constructivist tradition aiming to reveal how representation works and on what grounds members of parliaments represent. To answer questions about the nature of the representative process, researchers look at representative claims (Saward Reference Saward2006; Wilde Reference Wilde2013) – that is, statements put out by legislators (or possibly other actors) in which they claim to speak for a group of people (Bird Reference Bird2015; Celis Reference Celis2006; Lončar Reference Lončar2016). In this tradition, Lucy Kinski (Reference Kinski2018), for instance, asks whether we observe a process of Europeanization of representation and she reveals that national representatives claimed to speak for the European citizens rather than their national electorate when debating the European Financial Stability Facility in Austria, Germany and Ireland. So far, studies in this tradition tend to focus on analyses of plenary debates only, often in the context of a specific topic since it requires in-depth analysis. However, whom representatives claim to represent might vary according to the audience addressed in certain types of written communication. Studies that take different types of parliamentary record into account might reveal new patterns of claim-making in parliamentary questions or justifications for legislative drafts that have so far been overlooked.

Example analyses

To give the reader a more precise idea of how this data set can enrich the field of legislative studies, this final section of the research note presents two brief examples. First, we demonstrate how MPs’ legislative productivity can be measured across the different document types, comparing future chairpersons to their party colleagues, with the intention of identifying typical career patterns of politicians. Second, we highlight how the exceptionally long time coverage of our data might enrich research on the representation of women.

Legislative careers: progressive ambition and legislative output – does diligence pay off?

Research on legislative career patterns has been greatly influenced by ambition theory (Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1966). Joseph Schlesinger's seminal work distinguished three different types of ambition among legislators: discrete, static and progressive. Whilst representatives exhibiting discrete ambition only want to hold their office or mandate for the specified term, static-ambitious legislators do seek re-election, but do not aspire to higher or more prestigious positions. An MP with progressive ambition, in turn, aims to move up the career ladder to a position or ‘an office more important than the one he now seeks or is holding' (Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1966: 10). Schlesinger argued that the different types of ambition should also manifest in distinct legislative behaviour and attitudes.

This supposed link has been of interest to various scholars. Analysing attitudes of European and Israeli MPs, Ulrich Sieberer and Wolfgang Müller (2017) assume that progressively ambitious representatives should voice greater support for behaviour that would allow them to maximize their individual visibility. They find that MPs striving for higher positions are indeed more likely to favour personal over party-centred campaigns and ascribe greater importance to appealing to party leadership at the national or regional level compared with the local party base (Sieberer and Müller Reference Sieberer and Müller2017). Furthermore, Rebekah Herrick and Michael Moore (Reference Herrick and Moore1993) confirmed that legislators who would eventually occupy leadership positions within the House of Representatives of the US rank among the most active MPs – for example, with regard to speechmaking or bill sponsorship – even during their first term in office.

Even though parliamentary dynamics in Germany (or any parliament with strong party discipline) differ widely from the US, legislative initiatives imply a high visibility for the legislators involved and could arguably attract those with a progressive ambition and a desire to stand out from their colleagues. In the German case, the assignment of speech time runs through a process of coordination among the leaders of party groups, and bills are almost without exception introduced by the government or party groups. This also holds true for other types of legislative initiatives. Nevertheless, groups of MPs in the Bundestag can theoretically table motions and minor or major requests independently from their party through a quorum of 5% of all members and they occasionally do take such action (Ismayr Reference Ismayr2012). We hence aim to see whether legislators with progressive ambition are more likely to engage in activities independent of or opposed to their party group.

To test this expectation, we analyse the frequency with which MPs submit motions and interpellations, under the condition that they were tabled by groups of MPs without the support of a party group.Footnote 3 We compare MPs who would in a future electoral period chair a select committee with the figures for all MPs in the respective period. Not least because the Bundestag represents a working parliament, committee chairs can be considered important and prestigious leadership positions in the German legislative branch. Members eventually chairing a select committee in parliament can thus be expected to exhibit relatively high levels of progressive ambition, which should in turn find expression in an above-average legislative output, as well as the desire to gain visibility and reputation. The analysis covers the first to 16th legislative periods and, during this time, the number of minor interpellations without the support of a party group amounts to 1,730, while the number of different motions meeting this criterion comes to 1,145.Footnote 4

Figure 3 allows us to compare the mean number of non-party interpellations and proposals of all future committee chairpersons to the overall average per MP. First, the results show that the mean values for both types of communication fluctuate strongly over the course of the period under investigation. While the sixth electoral period saw record numbers of 21.8 interpellations per MP and 30.8 per future committee chairperson, almost no interpellations without the support of a party group were tabled between the ninth and 11th as well as between the 14th and 16th electoral period. Similarly, the mean numbers of non-party motions also differ substantially over time, and scarcely any were put forward during the sixth, eighth and ninth electoral periods. Where the means are not close to zero, however, we find some support for our expectation: with very few exceptions, MPs who would eventually go on to chair a select committee are indeed more inclined than the average legislator to table non-party motions or interpellations. Taking legislative matters into one's own hands thus appears to be a practicable strategy to gain visibility and reputation, even though it involves bypassing a party group and its leaders.

Figure 3. Average Number of Non-Party Interpellations and Proposals by All MPs

Since both motions and interpellations represent instruments more frequently employed by opposition parties, a closer look at the effect of the governmental context and MPs’ party background is desirable. Figures 4a and 4b present the mean numbers of non-party interpellations and proposals supported by future chairpersons of the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) and Social Democrats (SPD) in comparison with their party colleagues. The results indicate that the legislative output of interpellations and proposals is indeed influenced by the governmental context: the mean number of non-party interpellations put forward by CDU/CSU MPs increased sharply when the SPD first led the government in the sixth electoral period.

Figure 4a. Average Number of Non-Party Interpellations and Proposals by CDU/CSU MPs

Figure 4b. Average Number of Non-Party Interpellations and Proposals by SPD MPs

When social democrat Gerhard Schröder succeeded Christian democrat Helmut Kohl in the 14th electoral period, MPs belonging to the new governing party tabled substantially fewer proposals than in previous years and virtually none without support of the whole party parliamentary group. More importantly, though, future committee chairpersons of both the CDU/CSU and the SPD were more active than their party colleagues in almost all electoral periods that saw a relevant number of non-party motions tabled independent of their role as opposition or government party member. As our results are consistent both over time and across different types of documents, they lend support for our hypothesis that legislators with progressive ambition are more likely to engage in legislative activities independent of their party group. The new data set hence provides researchers with a rich source to test established arguments such as ambition theory.

Representation: are gendered patterns in questioning activity stable over time?

An extensive set of literature studies gender differences in the behaviour of representatives in Germany (Höhmann Reference Höhmann2019) and beyond (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014; Baumann et al. Reference Baumann, Debus and Müller2015; Bratton Reference Bratton2005; Childs Reference Childs2001; Lovenduski and Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris2003; Swers Reference Swers2002). This set of contributions shows that women set different issues on the parliamentary agenda – albeit to different degrees depending on factors such as the electoral context or the ideological position of their party. Female legislators more frequently than their male colleagues engage with issues that pertain to the equal treatment of men and women, child and health care, education and redistribution. Studies in this field usually compare women's representation by investigating rather short time horizons. However, potential moderating factors for the relationship between representatives’ gender and their legislative activity might vary over time, thereby leading to different findings depending on the investigated time period. The share of women in parliaments (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup1988; Frederick Reference Frederick2009), the presence of critical feminist actors (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009) or specific events such as abuse scandals and salient cases of rape might reinforce or mitigate gendered behavioural patterns of politicians. The time-series format of our data set allows to test whether and to what extent differences in legislative behaviour driven by gender changed over time.

To demonstrate how our data set allows researchers to answer this and similar research questions, we study oral questions submitted by legislators. Various studies use parliamentary requests to capture MPs’ legislative priorities in systems with high levels of party discipline, because single MPs can submit them autonomously, and use this to give information about the priorities of individuals. We identify all questions that include the keywords child (or children (Kind in German)) as well as any word combination including this word fragment (such as childcare (Kinderbetreuung) or child benefit (Kindergeld)). Engaging with children's well-being, their safety, education and care can be labelled a women's issue according to traditional role models, because it relates to education and childcare.Footnote 5

The lower part of Figure 5 presents for every plenary meeting the share of all questions submitted by male and female legislators that are in one way or the other concerned with children. As suggested by the theory, we observe that, since the late 1940s, women in the German parliament were more likely than men to submit requests on this subject. The visible fluctuation before the 1970s is mostly explained by cases in which female legislators did not submit any questions for a plenary meeting. However, the longitudinal data also reveal that the strength of this gender gap in questioning priorities decreased over time. It was most pronounced in the early decades, but, while persistent, is considerably smaller in more recent years. Notably, this modification is not a consequence of increasing numbers of questions submitted by men, but actually decreasing significance of the topic in women's questioning activity.

Figure 5. Oral Questions Submitted by Male and Female Representatives Including the Keyword 0 ‘Child’ in Germany between 1949 and 2017

Note: Figures show average of all men/women in parliament.

Overall, this descriptive analysis indicates that context matters for studies of representation. The policy priorities of male and female legislators shift over time. These insights suggest that studies of women's representation in the 1960s, 1980s and 2000s would reach very different conclusions about the extent of gender differences in parliamentary activities. Our data set thus enables researchers to develop a more nuanced, context-sensitive picture of how legislative behaviour more broadly changed over time.

Conclusion

The new data set presented in this research note covers all parliamentary material published by the German Bundestag after 1949, with the exception of debates. The rich data enable researchers working with requests, responses and briefings, reports, bills or decrees, proposals and other types of parliamentary activities undertaken by MPs and government members to ask a whole new range of research questions. Over and beyond, this new material allows us to test whether established empirical insights might be generalized over time and for various types of plenary documents. The examples presented here showed how this data set might enrich research on legislative careers and women's representation, and the data will constitute a valuable source for a broad set of scholarship engaging with parliaments, parties and representatives.

Even though in-depth analyses of the texts are possible for German-speakers only, most information is accessible even for those who are not (that) familiar with the German language. This includes, for example, the frequency of occurrence, such as who asks how many parliamentary questions (addressing which ministry), or co-sponsorship of legislative drafts or proposals. Furthermore, single or multiple keywords can provide, at least to some degree, access to the substance of the documents in the data set for non-German speakers.

This data set makes Germany the only case for which all parliamentary material is available for scholarly work. We would like to strongly encourage other scholars to provide the service to the discipline and prepare comprehensive data sets for other countries, because merging our data with similar projects in the future will allow for yet another new comparative research agenda.

Acknowledgements

Both authors contributed equally to this paper. We would like to thank Dzaneta Kaunaite, Jonas Dietrich and Emily Brandes for their assistance on this project. Moreover, this article benefited from useful comments by three anonymous reviewers and the participants of the inaugural meeting of the research group on parliaments of the German Political Science Association in Frankfurt in October 2019. Tobias Remschel holds a Georg-Christoph-Lichtenberg scholarship, funded by the Ministry for Science and Culture of Lower Saxony, Germany.