The Oslo Accords, signed between the government of Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization in 1993, mark a significant turning point in the history of the Middle East as it was assumed to herald Palestinian self-determination and regional stability. Since then the administrative, social and not least cultural environment of the territories has structurally transmogrified through international development aid flows and neo-liberal policies even as Palestinians are no closer to realizing these objectives. Moreover, despite the general academic consensus that internationally sanctioned peace-building programmes undercut these ambitions instead of stimulating them, the vocabulary of conflict resolution through development remains a paradigmatic model for Palestinian and foreign governments. Consequently, several studies have argued that Euro-American development experts, who emerged after the post-Cold War termination of competing bilateral financial assistance, should be included in the assortment of powerful agents that economically and politically transmuted the region.Footnote 2

The objective of this article, following the growing consensus on the negative repercussions of neo-liberal state building and development, is to offer a critical evaluation of the impact of foreign aid on theatre in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT). Despite an overwhelming body of governmental and non-governmental documentation and literature on theatre in conflict zones, the institutional links between ‘culture’ and ‘conflict’ are seldom problematized. By first historicizing the institutionalization of Palestinian theatre and subsequently analysing its imbrication in the human rights industry through the example of the Freedom Theatre, this article complicates the conception of development as a neutral, disinterested, technocratic exercise divorced from arts practice. As a corollary, it will also complicate the dominant narrative that theatre in conflict zones facilitates empowerment, decolonization and cultural resistance. Although foreign aid provided the material conditions for the institutionalization of Palestinian theatre, in accordance with broader geopolitical strategic goals it concurrently promoted a structural dependency that undercut Palestinian anti-colonial agency. Just as Palestinian economic development has been described as skewed, stalled or impoverished, so also Palestinian cultural development has neutralized cultural resistance and generated a ‘phantom sovereignty’ directed towards international development experts. By historicizing how the performing arts were subsumed within the aegis of development in the OPT in the aftermath of the Oslo Accords, this study argues that the resultant restructuring of theatre through its ‘NGOization’ has jeopardized the objective of national liberation instead of promoting it.

The beginnings of international funding to Palestinian theatre

In 1984, the Ford Foundation, the first international agency to fund theatre in the ‘developing world’, granted $416,000 to the El-Hakawati theatre. In its battle to win the Cold War, the foundation had, by then, established an advanced ‘cultural-development’ model for soft-power activities in emerging countries.Footnote 3 As I have argued elsewhere, American foundations who were the first to recognize that ‘there may be more to development than socio-economic considerations alone’ facilitated the development of a transregional knowledge economy through the creation of networks of aid-dependent artists and cultural institutions.Footnote 4 While the foundation had several decades of experience in South Asian theatre, its foray into the arts of the Middle East in the 1980s was unprecedented.

Before 1984, theatre in Palestine had an extensive history. Prior to the Nakba of 1948, indigenous performance forms such as the dabkah, al-hakawati (travelling storyteller), sunduq al-dunia (magic box) and khayyal az-zill (shadow theatre) were a mainstay of the Palestinian landscape. Although the war of 1948 has been described as a setback to the theatre movement, the Palestinian theatre revived after the war of 1967. This event marked not only the Israeli occupation of East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza, but also the rise of Palestinian nationalism and ‘cultural resistance’ that took several forms – from adult education to the revival of performance traditions and folklore.Footnote 5 Grass-roots organizations emerged that (along with trade associations and a student activist movement in universities in Bethlehem, Jerusalem and Nablus) prompted an unparalleled mobilization of Arab society and consolidated a Palestinian theatrical movement.Footnote 6 In 1972 François Gaspar, known to the world as François Abu Salem, established al-Balalin (the Balloons). Along with other troupes such as Dababis (Pins) and Sunduq al-’Ajab (the Wonder Box), al-Balalin marked a significant turning point in the Palestinian theatre movement. Companies performed plots from the Thousand and One Nights in the Palestinian vernacular rather than classical Arabic, using indirect allusions to contemporary events in order to avoid censorship.Footnote 7 ‘It was a Palestinian theatre, by Palestinian people, serving a Palestinian cause, before Palestinian audiences.’Footnote 8 But their productions, according to a Ford Foundation report, were amateurish. None had a regular budget, rehearsal hall or staff, and their actors worked full-time in other jobs and rehearsed in the evenings and on weekends. Most of the groups allegedly died out by the 1980s, although one managed to continue: the El-Hakawati Theatre Company, established by Abu Salem in 1977 after the disbanding of al-Balalin and a second company that he helped establish, Bilaleen (Without Mercy).Footnote 9 It is with the founding of the El-Hakawati Theatre that the ‘institutionalization’ of Palestinian theatre commences, characterized by the establishment of playhouses, professional actor-training schools, regional and international cultural networks and the creation of big-budget theatre productions.

Raised in Jerusalem but holding French citizenship, Abu Salem was responsible for training the company and developing its improvisational style of production as he was the only one in the troupe who had formal theatre training, having studied at the Centre de l'Est in Strasbourg and worked with the Théâtre du Soleil in Paris.Footnote 10 Accordingly, Abu Salem functioned as a cultural interlocutor between Europe and the OPT, a role repeatedly emphasized in press reportage and theatre scholarship, even as another member of the troupe, Jackie Lubeck, brokered the first funding agreements between the theatre and international foundations.Footnote 11 By 1984, the troupe had produced at least five plays; its membership had grown from seven to fifteen persons; its tour schedule in Israel, the West Bank and Europe had ‘tripled’; and its annual operating budget was $82,650 (including $15,000 for rent and $48,000 for the salaries of ten full-time technicians and actors).Footnote 12 Through savings and donations from wealthy Palestinians, the group managed to rent the previously burned-down Al-Nuzha movie theatre in Jerusalem in October 1983. Lubeck initially approached the Ford Foundation for assistance with the theatre's renovation programme but was then directed by Ford's officers towards soliciting funding for its theatre programme as a whole.Footnote 13 At this time, Ford had merely a fledgling arts programme in North Africa.Footnote 14 After seeking advice from its geopolitically strategic India office, Ford's Cairo office decided to fund El-Hakawati in order to develop ‘networks for training, support and management of the arts in different third world settings’.Footnote 15 Lubeck, unsure of what the troupe could solicit funding for, asked foundation officer Ann Lesch for ‘hints’.Footnote 16 After in-person meetings in Jerusalem in May 1984, it was agreed that core support of $100,000 over a two-year period would be divided into operational costs (including supporting productions and the salaries of full-time staff) and workshops for children and adults, thus setting in motion a format for theatrical activity in the OPT and other conflict zones that exists to this day.Footnote 17

As early as April 1984, Linn Cary, assistant programme officer and subsequently assistant to the president of the Ford Foundation, asked, ‘what is the relation of the workshop programs to the overall objectives of the theatre? The workshops’, Cary wrote, ‘would certainly not serve to advance them as a professional theatre group’.Footnote 18 Despite these concerns, additional support of approximately $300,000 was granted by Ford to both workshops on topics as diverse as poster and fabric design, as well as theatre productions, in 1986, 1988 and 1990. In so doing, Ford facilitated the development of the institutionalized Palestinian theatre from the beginning as both ‘professional’ and ‘community-focused’, a double character epitomized by El-Hakawati's then confused identity between company and non-profit organization.Footnote 19 Therefore, while the troupe toured to rave reviews across Europe and North America,Footnote 20 it also ‘familiarized children with playing theatre games’.Footnote 21

The growth of the theatre was nevertheless not ‘entirely smooth’.Footnote 22 In 1989 during the First Intifada, the troupe distanced itself from the activities of the Al-Nuzha theatre. The playhouse had, by then, become a community arts and cultural centre, its Board of Directors having created a set of activities independent of those of the troupe.Footnote 23 This significant change transpired because El-Hakawati had ‘rarely been in Palestine’ due to its extensive touring schedule and was therefore accused ‘of catering primarily to a Western audience, leaving out the Palestinian community in the Occupied Territories behind’.Footnote 24 As Abu Salem poignantly prophesied of the future Palestinian theatre,

El-Hakawati is a moving project … it goes wherever it can go, wherever it can survive, in terms of its identity and in terms of its economical survival. We have hardly ever chosen being abroad. Strange. I think, that sounds like the essence of what it is like to be a Palestinian, a Palestinian refugee.Footnote 25

The ‘fundamentally diverse’ visions of the Al-Nuzha theatre – as a community centre for diverse groups and a rehearsal space for El-Hakawati – thus spelled the break-up of the first ‘professional’ Palestinian theatre company.Footnote 26 Although Abu Salem relocated to Europe, the precedent that he had laid was swiftly followed. While the new Al-Masrah for Palestinian Culture and Arts set up at the Al-Nuzha theatre received funding from Ford to produce plays for children,Footnote 27 many of the erstwhile members of El-Hakawati set up a new company in 1992, The Jerusalem ‘Ashtar’ for Theatre Training and Performing Arts.

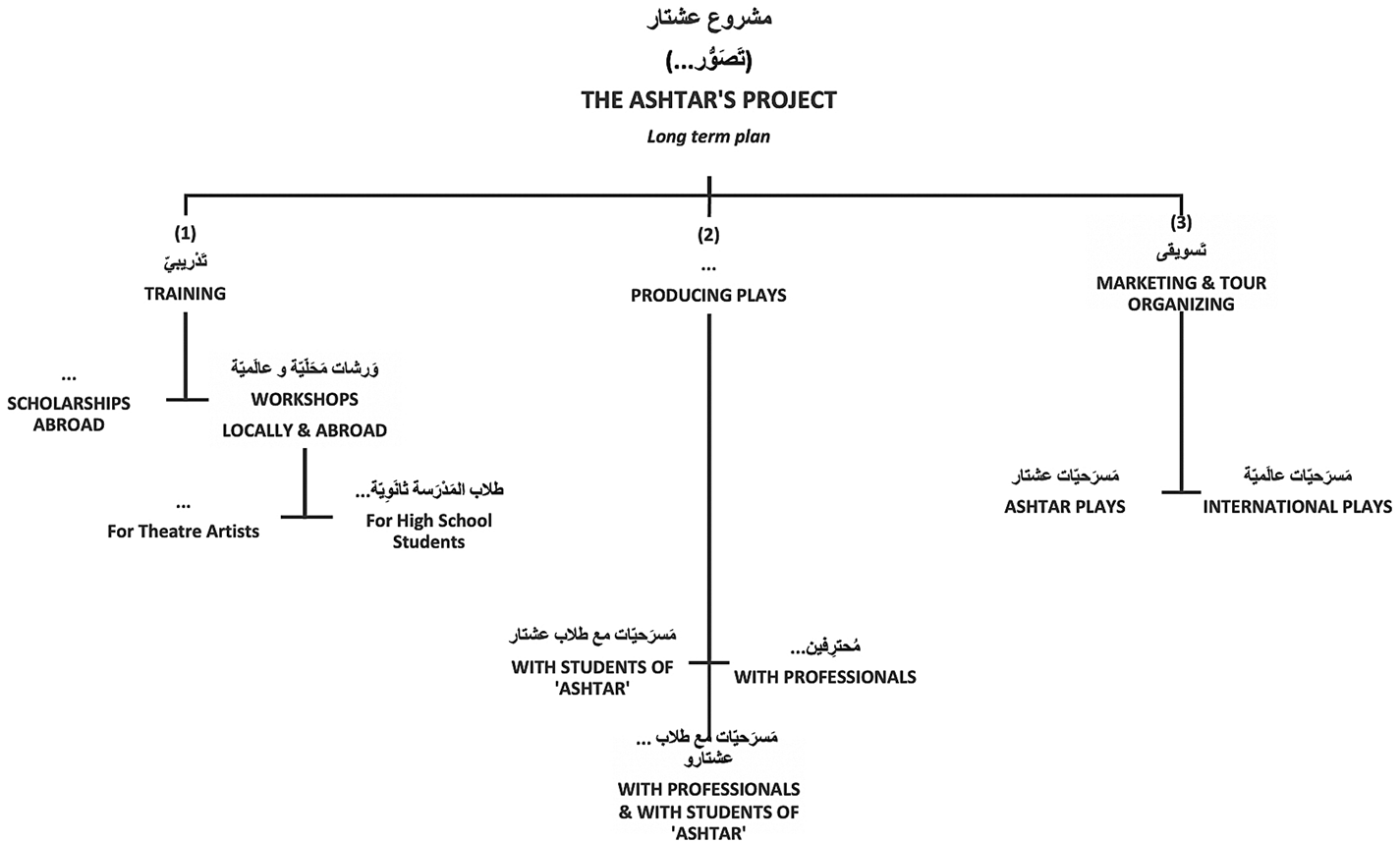

Having received core expertise in fundraising, theatre production, international touring and community work at El-Hakawati, Edward Muallem and Iman Aoun approached Ford for $40,000 in support for a theatre pedagogy programme. Ashtar therefore further developed the children's workshop/professional-production model instituted by El-Hakawati through both experimental plays and workshops in secondary schools that would ostensibly give ‘students a framework in which they can explore and develop their feelings, learn skills for coping in a society oppressed by occupation, and … mitigate the destructive influences of a violent environment’.Footnote 28 A neatly prepared graph thus summarized Ashtar's programmatic foci (Fig. 1).Footnote 29

Fig. 1 Graph of the long-term plan of the Ashtar Project. (Illegible terms denoted with …). ‘Ashtar for Theatre and Performing Arts, Educational Project, Year II, 1993’. Rockerfeller Archive Center.

Significantly, Ashtar's grant applications – which stipulated target audiences for its workshops; professional collaborators in the US and Europe; ‘human’, ‘educational’, ‘artistic’, ‘cultural’ and ‘economic’ aims; the involvement of women in their staff; and comprehensive budgets, timelines and financial reports – were more professional, reflecting an awareness of the changing philanthropic landscape of the OPT and a considerable effort to make Palestinian theatre legible within a development optic.Footnote 30 Accordingly, Ashtar managed to procure funding from the Associazione Ricreativa e Culturale Italiana (ARCI), Caritas Switzerland and Cassinelli Vogel Foundation, even as it was negotiating grants with the American Consulate, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), the British Council and Pro Helvetia.Footnote 31 During the tempestuous period during and shortly after the signing of the Oslo Accords, many of these organizations established a physical presence in the OPT, thereby contributing to a sudden spurt in cultural activity. While the Ford Foundation broadened its field of action, European agencies such as SIDA, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and numerous other government representations began funding a growing number of theatres – now restructured as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) – in the territory administered by the new Palestinian Authority (PA). No longer subject to the Israeli Committee for Censorship of Plays and Films and the Israeli two-tiered permit system to stage plays in the West Bank, the centre of gravity of Palestinian culture shifted from East Jerusalem to the West Bank. While Ashtar and the Al-Kasaba Theatre moved base to Ramallah, Lubeck founded Theatre Day Productions (TDP) in November 1995. Other centres, such as the Alrowwad Cultural and Theatre Training Center (1998) in Aida Refugee Camp, Bethlehem; Al-Harah in Beit Jala, Bethlehem (2005); the Freedom Theatre in Jenin Refugee Camp (2006); and Yes Theatre in Hebron (2008), followed. Moreover, with the shift in performing-arts funding, from self-funding and private funding to development aid, theatre NGOs began to operate on a professional scale, building or renting theatres, theatre schools and/or cultural centres; employing salaried staff members; and developing programmes, budgets and grant applications. What, however, does this short history of the institutionalization of Palestinian theatre tell us about a new mode of Palestinian performance? What had cultural resistance to the Israeli occupation become and who, above all else, was the Palestinian theatre's audience?

Human development

Criticisms of applied theatre are not new. The instrumentalization of theatre by development experts in the service of ‘social change’, ‘empowerment’ and ‘good governance’ and the concomitant devastation of political language, socialization of intellectual elites and normalization of particular values have been critiqued by scholars such as Tim Prentki, Syed Jamil Ahmed, Joseph Odhiambo and Jane Plastow.Footnote 32 However, I would argue that theatre which operates in the service of development assumes a distinct function in conflict zones, of which the Palestinian case is paradigmatic. In the aftermath of the American triumph in the Cold War, the language of cultural development, a descriptor for soft-power activities in non-Western states, swiftly transmuted from the consolidation of an American presence through cultural preservation to the strengthening of ‘human rights’ through the arts. This change was brought about through a shift in the World Bank's conception of development from structural-adjustment programmes (SAPs), which highlighted continuous economic growth through privatization and the liberalization of markets, to ‘human’ or ‘social’ development.Footnote 33 In the 1990s, critics lambasted SAPs, a neutral, universal developmental force ‘disembodied from culture’,Footnote 34 as inimical to ‘development’. Instead, the UNDP's seminal first Human Development Report (1990) delineated ‘the essential truth that people must be at the centre of all development’.Footnote 35 The report, as Toufic Haddad notes, spearheaded the disaggregation of the role of the state in development by Western donor governments, the United Nations and international financial institutions (IFIs).Footnote 36 Previously, ‘social priorities’ such as basic education were part of a state-centred model of development informed by national economic policies and public social-welfare systems. With the liberal-peace model, their delineation as isolated problems disassociated from territorial conflict, political sovereignty and wider economic development allowed for numerous developmental agents to focus on them independently. Hence development as conceived by the World Bank functions as an ‘anti-politics machine’ involving recognition of topics associated with the political situation (for example, Israel's destruction of Palestinian agricultural industries); then endeavouring to insulate the economic dimensions from the political (separating lack of water and poor produce from deliberate diversions of water, Israeli control of Palestinian markets and so on). This is followed by efforts to solve the former rather than the latter (in this case, through an emphasis on environmental issues).Footnote 37 The ‘civic’ thus replaces the ‘national’ and ‘political’, discursively evincing the neo-liberal belief that armed conflicts can be absolved through the power of global finance.Footnote 38

Accordingly, as Leila Farsakh contends, foreign aid in the OPT is guided by the strategic goal of peace building or terrorism fighting rather than economic development, reinforcing what Sara Roy has influentially termed ‘de-development’.Footnote 39 While definitions of ‘underdevelopment’, Roy argues, allow for structural transformation and improvement, de-development not only warps the development process but also comprehensively undermines it. By addressing the externalities of the conflict, the structural determinants of de-development – the expropriation of critical Palestinian resources, the progressive integration of the Palestinian economy with the Israeli market and restrictions on the development of Palestinian national institutions – are disregarded and settler colonial reality is further entrenched.Footnote 40 Underdevelopment, as Adam Hanieh notes, ‘thus becomes the fault of the oppressed themselves, not a situation primarily conditioned by the prevailing structures of power; the oppressed must rise to the challenge of unlocking an innate potential for development’.Footnote 41 The ‘local’ or ‘individual’ rather than the ‘national’ or ‘communal’ becomes the site for empowerment, for good governance and for peace building and state building, providing legitimacy to international development interventions, the caretaker government of the PA and NGOs working towards the fulfilment of ‘human rights’.Footnote 42 The controlled, partially self-governed PA paid for by the international community, according to Raja Khalidi and Sobhi Samour, ‘is replete with seductive appeals to plurality; accountability; equal opportunity; the empowerment of its “citizens”’, thus faithfully reflecting the agenda of the World Bank even as it functions merely nominally as a democratic entity.Footnote 43 Similarly, the rise of development brokers had a direct bearing on the Palestinian landscape, transforming grass-roots organizations with strong ideological leanings into professional entities with links to the international community and/or the PA – even as human rights violations that could not be named as such gathered breakneck speed. ‘Apolitical (and therefore, actually, extremely political)’, the depoliticization of NGOs through capital interferes with traditionally self-reliant indigenous people's movements, turning resistance into ‘a well-mannered, reasonable, salaried, 9-to-5 job. With a few perks thrown in’.Footnote 44 But what does this have to do with theatre and performance?

Palestinian performance

Of critical importance is the use of the language of performance in development literature on Palestine: from the ‘“stagiest” approach to achieving Palestinian rights’, the masking of reality by Fayyadism, the transformation of Palestinians into ‘spectators to their own ongoing tragedy’, and the ‘shared charade’ of human rights that ‘was a pretence, a façade that everyone recognized as such but was feigning to keep up nevertheless.’Footnote 45 Imbricated in Palestinian notions of performance is the conceptual distinction between ‘human rights’ (e.g. rights to freedom of movement and assembly) and the ‘human rights industry’, described by Lori Allen as the complex of organizations and actions that operate under the name of human rights, comprising the experts employed by these institutions, the methods they use and the system of aid that this industry produces and relies on.Footnote 46 It is the human rights industry that predominantly conditions institutionalized Palestinian representational forms before the world: from individual claims of Palestinian humanity and modern citizenship to the performance of human rights and statehood by the proto-government of the PA. Consequently, performances of universal human rights not only shape Palestinian calls for justice to the international community, but also simultaneously produce an ‘ideological mask’ to legitimize the state before international bodies – even as popular nationalist politics and forms of representation are rendered illegitimate.Footnote 47 As Palestinians view the PA as complicit in the occupation, the NGOs as wilful players reliant on a steady cash flow and the international donor community as incapable of stopping Israeli atrocities and opponents of true democratic freedoms, their co-enactments of human rights are perceived as disciplinary mechanisms that normalize Palestinian subjects and supplant anti-colonial politics, thereby producing a ‘bad-faith society’ of peoples disbelieving these performances.Footnote 48 Paradoxically, therefore, while the language of human rights espoused by the PA, NGOs and donors makes Palestinian humanity globally legible, validating the administrative and economic viability of a Palestinian state-to-be, it draws local attention to the fragility of its claims due to its depoliticization of the Palestinian struggle.

At stake, therefore, according to Allen, are two contesting moral economies, political imaginaries or forms of ideological claim-making, the one directed inward based on populist ideals and local legitimacy and the other outward based on compliance with international human rights law.Footnote 49 Similarly, Rania Jawad describes a Palestinian performance-based logic, one based on confronting colonial power directed to local Arab spectators, the other on instituting neo-liberal governing institutions that speaks to Western-dominated organizations.Footnote 50 Despite often being critical of the NGO-ization of Palestinian culture, theatre practitioners are, due to the necessity of funding, largely compelled to adopt visible signs of adherence to the second, humanitarian frame. A 1998 report by Ashtar states that ‘theatre groups nowadays are mostly concerned with raising certain existential topics like Democracy, Human Rights … by presenting them as they surface in the social, political and economic issues of daily life’.Footnote 51 Not dissimilarly, the ‘main vision’ of Al-Harah is ‘to assist in building and maintaining a civil society that promotes human rights, democracy and freedom of expression’.Footnote 52 Through workshops and community projects, theatre directed at community welfare transforms into a mission civilisatrice where Palestinians are socialized into a normative, rights-based culture defined by terms such as ‘civil society’, ‘democracy’ and ‘gender equality’. By adhering to the criteria of normality set by Western-dominated IFIs, individual Palestinians – the target of artistic interventions – assume the burden of finding solutions to the social ruin caused by settler colonialism. In this regard, a train of development experts, from the World Bank's technocrats, through representatives of donor networks, down to grant writers and arts managers, ensure that Palestinian theatres like the PA, which they typically despise, mutually work towards the building of a neo-liberal Palestinian state. Simultaneously, the arts are increasingly divorced from pre-existing political attempts (e.g. Islamist) to address the structural domination of Palestinians by both the Israeli occupation and a suppressive neo-liberal regime.

While the humanitarian logic of artistic workshops intended to stimulate social change is palpable, a more nuanced figuration appears in professional Palestinian theatre productions such as the Freedom Theatre's interpretation of Waiting for Godot (2011). When the actor Eyad Hourani pronounces, ‘I'm waiting for all of us to be human’, humanity becomes a performance where to be Palestinian is not to be human but to pass as human through an act of sociopolitical translation.Footnote 53 Performed in a mix of Arabic and English in the Jenin refugee camp, the English subtitles for the benefit of international audiences correspond with an epistemological resignification of cultural practice through a humanitarian framing. The potent idea that Palestinians have been misrepresented on the global stage and need to reclaim their narrative shapes the claims actors make and who they make those claims to. Critical here, however, as Jawad notes, is the risk of associating the language of human rights with that of anti-colonial protest.Footnote 54 The logic of ‘I'm just like you and I too am deserving of human rights’, equivalent to the peace- and state-building discourse of the PA, grants the global witness, typified by international donor bodies, the ability to assess Palestinian enactments of humanity, thereby denuding the language of protest of political power. For example, the governments of Norway and Denmark withdrew funding from a cultural centre in Burqa as the centre was named after Dalal Mughrabi, a female freedom fighter who spearheaded the 1979 massacre of Israeli civilians on a highway near Tel Aviv.Footnote 55 Subsequently, the Swiss government stopped sponsoring the Palestinian NGO Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law Secretariat through which funds had been channelled to the centre, and in 2017 Belgium stopped its sponsorship of Palestinian schools as one such institution had been named after Mughrabi.Footnote 56 Implicit in the penalization of Palestinians for commemorating their heroes is a warning to recipients of international funding – that free speech is not free. Accordingly, between the polarities of victimhood and agency and through appeals to developmental universalisms, Palestinian humanity becomes intellectually coherent or legible for a global audience and Palestinian theatre becomes a site of general equivalence and international exchange even as local publics are increasingly estranged.

Phantom state, phantom resistance

The Freedom Theatre, a ‘community-based theatre and cultural centre’, in many ways is prototypical of the post-Oslo predicament of Palestinian theatre.Footnote 57 It was established in 2006 by Jonatan Stanczak, Zakaria Zubeidi and Juliano Mer-Khamis, the son of a Jewish mother and Palestinian father who received international acclaim as an exceptionally gifted actor and director. The Freedom Theatre was built on the foundations laid by Juliano's Jewish mother Arna, who established the Care and Learning Project in Jenin refugee camp and subsequently the Stone Theatre (named after the stones children would volley at Israeli armed vehicles). A culture of both peace and sumud (steadfastness) was implicit in the agenda of the centre, which not only functioned as a place of refuge for children through games and cultural activities but also helped disseminate prohibited resistance pamphlets. After her centre was bulldozed in 2002 with the Israeli invasion of the camp, many of Arna's children became leaders in the armed struggle against the Israeli occupation and, bar Zachariah Zubeidi, became martyrs by the end of the Second Intifada.Footnote 58

The Freedom Theatre was thrown into the spotlight when Juliano was assassinated on 4 April 2011, a few months before his predecessor, Abu Salem, the architect of the institutionalized Palestinian theatre, committed suicide. As the murderer was never found, Juliano's death has since been the subject of intrigue: from speculations of a killer contracted by discontented, influential figures in Israel or the PA, angered upholders of Islamic tradition, to petty personal vengeance. It is, however, difficult to dispute that support from the camp during and after his murder was lacking. Juliano's killer, who absconded in broad daylight from the middle of the camp, was neither obstructed nor seen by any of its sixteen thousand residents. Moreover, acts of mourning for martyrs in Jenin, marked by public processions attended by hundreds of people carrying pictures of the dead, were visibly absent in the camp.Footnote 59 The question, therefore, that I wish to begin to try to answer is not who killed Juliano, but rather why the camp, the people for whom the Freedom Theatre was ostensibly built, neither mourned him nor cooperated with the investigation.

Although the Freedom Theatre has been branded through militant terms such as ‘cultural intifada’ and ‘cultural resistance’, and although the theatre often emphasizes that its founders did ‘not attempt to replace other forms of resistance in the struggle for liberation – rather to join them’, the messages that it conveyed to donors, volunteers, international visitors and spectators through its interviews, publications and programmes were mixed.Footnote 60 When the American philanthropist Charles Annenberg visited the theatre before granting one of its first substantial donations of $200,000, Juliano argued, ‘I don't think the gun can free Palestine but I believe that culture, poems, songs, books can free Palestine and it already free a lot of people’.Footnote 61 Similarly, in a BBC interview he averred, ‘we are fighting a lot of fundamentalists that see what we are doing as a disgrace … We are fighting a lot of enemies, before, before we get to the Israeli soldiers.’Footnote 62 More significantly, at the Kunst.Kultur.Konflikt conference, Christa Meindersma, director of the Prince Claus Fund, quoted a student from the Freedom Theatre: ‘The theatre has given me the chance to become an actor instead of a martyr.’Footnote 63 The influence and the success of art in a crisis can hardly be expressed more clearly, the report of the conference concluded.Footnote 64

Perhaps Juliano and his teachers and students merely mouthed the words that development experts and government heads such as Meindersma wished to hear – a conscious self-ventriloquism. Perhaps above all else they desired a world-class, professional theatre in the camp and used all means to realize that challenging goal. Or perhaps they truly believed that they needed to ‘liberate the minds first and then liberate the land’.Footnote 65 However, the idea of cultural resistance subsuming violent conflict by means of a ‘universal’ freedom that would ‘achieve liberation from all the elements of the occupation, including the internal social oppression’, was a precarious one in a place that was proud of its militant past.Footnote 66 Although the theatre was vociferous in its critique of the PA and the Israeli occupation,Footnote 67 its primary focus on the individual and local, the ‘occupation from within’ as the site of cultural resistance, echoed the discursive and performative elements of Fayyadism that highlight the role of the individual in ensuring the smooth development of a liberal market and flourishing consumer economy.Footnote 68 The seemingly activist orientation of creating change agents, ‘civic imagination’ and leadership, effecting empowerment and decolonizing the mind to build credible partners for peace, typifies the ‘human-development’ model where the externalities of the conflict are cyclically addressed. The language of the human rights industry and its attendant moral economy thus reconfigures the language of resistance, such that the redressal of underdevelopment is aimed at one's own ‘oppressive culture’ rather than at a systemic imbalance of power. De-politicized phantom state building in line with the neo-liberal aims and ambitions of the World Bank thus augurs a soft phantom resistance whose energy is directed at proving the modernity; that is, the humanity of Palestinians and their capacity to sustain the Oslo peace process before the international community. When directed inward, weaponized terms such as ‘internal occupation’ and ‘internal siege’ become flaccid, emptying the theatre of emancipatory potential and undermining ‘cultural resistance’ such that its purchase on the external Israeli occupation is mitigated. Foreign aid places the predominant emphasis of resistance against and liberation from an intolerant, backward society, generating a spectral ‘cultural resistance’ for the audience of the international community, a caricature of protest against the Israeli occupation onstage. By citing the global language of human rights, national non-recognition becomes embedded in its apparent converse, the performance of emancipation,Footnote 69 and a ‘bad-faith society’ of to-be-reformed peoples disbelieving in the theatre's progressive mission is further entrenched.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the gender focus of the Freedom Theatre. Nearly all donor bodies, following the development agenda of the post-Washington consensus, emphasize ‘the promotion of gender-aware dialogue’, a policy that had a significant impact on Palestinian theatre that increasingly developed programmes ‘to promote social change with regards to gender-related stereotypes and prejudices’.Footnote 70 According to Hala Al-Yamani and Abdelfattah Abusrour, Juliano believed that ‘the struggle against the occupier must be accompanied with our struggle for liberating women’. In Juliano's own words, ‘How can I be liberated of Israeli occupation when I oppress my sister or my wife?’.Footnote 71 In written and video interviews in English, female students of the theatre's acting school often note how resistance for them entails fighting against societal ‘norms and traditions’.Footnote 72 Similarly, the website of the MDG Fund under the poignant heading ‘Palestinian Identity Unfolds on Two Stages’ describes the theatre's Waiting for Godot thus:

As the West Bank Palestinian leadership was preparing for its September statehood bid at the United Nations General Assembly, 20-year-old Mariam Abu Khaled was getting ready for a different drama … ‘On stage, I can do whatever I want,’ says Mariam, who came of age in the decade following the second Palestinian Intifada against Israeli occupation … Not only was the fabric of Palestinian cultural life shattered, but Palestinian society, always skeptical about girls’ involvement in theatre, had become increasingly conservative … ‘Art has the power to make girls feel better inside,’ says Miriam. She says it encourages her to take risks and to challenge the status quo that perpetuates the Palestinians’ political stalemate and that limits women's rights and equality. Her friend Batool agrees: ‘Today I have two struggles; to free myself as a Palestinian from Israeli occupation and to free myself as a woman in my society.’Footnote 73

The juxtaposition of the Palestinian bid for statehood with the ostensible achievement of the normative Millennium Development Goals (MDG) through theatre implies that the figure of the Palestinian woman was, first and foremost, a locus for demonstrating the capacity of Palestinians to reform their despotic culture and subsequently administer their own state.Footnote 74 It is the modernization of women through the theatre that will ‘challenge the status quo that perpetuates the Palestinians’ political stalemate’, bringing to fruition the project of peace building and state building. As in the nineteenth-century colonial ‘women's question’, the indigenous woman here becomes the sign of an inherently oppressive tradition and the site for its reconfiguration.Footnote 75 Suzanne Bergeron notes, in the context of the World Bank's appropriation of feminist discourse, that the developmental target category of ‘women’ is founded on a ‘colonial effect’, a formulaic account of Third World women as helpless, marginal and deprived – and consequently requiring expert humanitarian assistance.Footnote 76 By taking the freethinking, progressive Western woman as the norm against which the Palestinian woman is evaluated, development discourse abjures a comprehensive understanding of empowerment and liberation which comprises a dialogue on the circumstances in which Palestinians can assume operative political power to effect policy change. Modernization theory is repetitively enacted: ‘human rights are considered modern and non-Western cultures are hastily equated with inequality, patriarchy and religious fundamentalism’, even as local publics retreat further into alternative forms of social cohesion.Footnote 77

Juliano was not unaware of the risks of the project of emancipating Palestinian women through theatre. His chastising of female international volunteers who sunbathed on the theatre's roof in full view of the adjacent mosque, his rules prohibiting female staff members to socialize in public after sunset in the aftermath of the contentious Animal Farm (2009), and the videotaped premonitions of his death indicate that he recognized the danger if not the intractable contradictions in using development and peace-building aid to set up a professional, world-class acting school in the conservative Jenin refugee camp.Footnote 78 Shortly before his next production, an adaptation of Alice in Wonderland (2011), he confided,

now we are going to do our next scandal which is Alice in Wonderland, but our Alice is not a stupid girl who finds out that there is a caterpillar, our Alice is going to rebel. Tradition, religion, schools, papa and mamma, she is going to say, give me a break guys, I have my own way. That's dangerous.Footnote 79

Thus Alice, the only woman not wearing a hijab, escapes her engagement party and arranged marriage, symbols of the tyrannical tradition that oppresses women. On reaching Wonderland, she is declared leader of a subjugated people, yet she must persuade these people that she is not their true leader. Eventually, the White Queen, the true messiah emerges, and Alice returns to her real life and tells her betrothed that she refuses to marry him: ‘her engagement ring freed Wonderland, and Wonderland freed her from the ring’.Footnote 80 ‘Are the oppressors’, Samer Al-Saber asks, ‘the Israeli occupiers, the camp's traditionalists, or both?’ Shortly before the play's first performance on 23 January 2011, the student Mariam Abu Khaled, dressed as the Red Queen, advertised the production by shouting through a megaphone from the roof of Juliano's car. She was told by onlookers not to show her face in the area again.Footnote 81 A few weeks later, the now familiar refrain of ‘the suspicious theatre … whose only goal is to spread corruption and Western culture’, was echoed in pamphlets drafted by unknown militant groups.Footnote 82 A week after the last performance, Juliano was no more.

Conclusion

If Juliano's ambition was to create an outstanding professional Palestinian theatre school, he succeeded. Many of his pupils, the future leaders of a future Palestinian state, now pursue remarkable professional careers in theatres in Germany, the UK and the Middle East. Few have continued their work in Jenin, in stark contrast to his mother's students. Read against this narrative of rupture and exile, the theatrical notion of the ‘cultural intifada’ or ‘cultural resistance’, ‘a movement that harnesses the force of creativity and artistic expression in the quest for freedom, justice and equality’, becomes an oxymoron.Footnote 83 As Abu Salem prophesied, the Palestinian theatre ‘goes wherever it can go, wherever it can survive, in terms of its identity and in terms of its economical survival. We have hardly ever chosen being abroad’.Footnote 84 Operating both as utopia and as heterotopia, depending on who is doing the spectating, the Palestinian theatre appears mirror-like where resistance and statehood manifest as real and unreal; apparitions refracting but not existing in reality. Not unsurprisingly, Palestinian recipients of EU cultural funding thus condemn, ‘You want us to look the same as you’.Footnote 85 By deflecting a core local constituency of intellectuals from the origins of the conflict to the externalities, liquid capital smooths over the impenetrability of borders, global humanity is standardized, resistance is fetishized, and culture is subsumed within a larger ecosystem of funding, normalization and biopolitical governmentality. ‘To be free is to be able to criticise, to be free is to be able to express yourself freely, to be free is to be free first of all of the chains of tradition, religion, nationalism, then you can start for yourself,’ Juliano once said.Footnote 86 Who was Juliano speaking to? Who was his audience? And who was he? Was he, as he was often made out to be, a wilful ‘infant terrible’ [sic] desiring an unalloyed, absolute freedom from the PA, Israel, Islamic tradition and all societal norms,Footnote 87 or a scapegoat in the complex clockwork of Euro-American soft power at the dawn of the Arab Spring? If the latter, isn't everyone in the wide parasitic network of the human rights industry – heads of government representations, global development experts, international theatre scholars, and ex-volunteers – who derived social and economic capital from parachuting into Palestinian lives, winning for them chimerical rights and freedom, to a degree complicit in his death (Fig. 2)?

Fig. 2 Image of a scene from Variations on a Love Song (2010), co-directed by Giovanni Papotto and the author during their time as volunteers at the Freedom Theatre. Photograph by Lazar Simeonov.

‘I think it is extraordinary that we live in a world where a foundation like yours can help a group like El-Hakawati’, Abu Salem wrote.Footnote 88 He spoke only too soon.