This review has three connected purposes: to provide an overview of some of the key interventions in anglophone literature on Latin America's Cold War produced since the early 1990s; to offer a new, multi-layered analytical model; and finally to use the example of Mexico to demonstrate both the weaknesses of the current literature and the potential utility of a new approach. At its heart are two seemingly simple questions: what, and when, was the Cold War in Latin America? Unlike some of the authors cited below, this review argues these do not have straightforward answers – if they even have answers at all.Footnote 1 In this, as in other respects, it takes its cue from Tanya Harmer's recent observation that

[W]hat the Cold War meant in a Latin American context or to Latin Americans is still relatively unclear. Scholarship is largely fragmented between different countries and time periods. There is little agreement about when the Cold War in the region began and ended, whether it was imposed or imported and precisely how it evolved over time. Some argue that the very concept of the Cold War is irrelevant in a Latin American context. Others contend that the region's Cold War set something of a precedent for what happened elsewhere. In short, we still have a lot to learn.Footnote 2

Indeed, the growing literature on Latin America's Cold War has spawned a paradox, which Alan McPherson has summed up neatly: ‘the more historians find out about the Cold War in [Latin America], the more the Cold War itself fades into the background’ – a point that many Latin American scholars have, I think, well understood for some time.Footnote 3 From these ‘hot zones’ often regarded as mere peripheries, nuclear codes and presidential summits seem so very far away. Vanni Pettinà recently synthesized these ‘problems of interpretation and chronology’ and this review builds upon some of the structural points he has raised.Footnote 4 His definition of the period as one during which the region saw ‘a substantial increase in US interventionism, dramatic internal polarization, and the long term strengthening of conservative forces’ is a very useful point of departure.Footnote 5 Pettinà's motivation ‘to evaluate the ways in which Latin American actors adapted to the regional changes that were produced by mutations in the US hegemonic project, global and regional, registered after the confrontation with the USSR began’ is shared here, though I pay particular attention to the links between such changes and adaptations, and longer-term structures and processes.Footnote 6

In attempting to map a route towards possible answers to some of these quandaries, this review offers a new interpretative and chronological framework for Latin America's Cold War. It stresses both the importance of underlying and long-standing economic, political, and ideological conflicts, and the need to consider regional particularities and different scales of analysis. At what point do the specificities of, say, Guerrero's Cold War negate the idea of Mexico's Cold War, undermining in turn the idea of Latin America's Cold War, and ultimately pulling the rug from under the concept of the global Cold War? It is clear, then, that it is not enough to ask when the Cold War took place in Latin America, importing frameworks from elsewhere. We must ask, instead, when, and how, the Cold War was Latin American. This article rejects the general weighting of the anglophone literature towards ‘late’ and ‘mostly peripheral’ interpretations, and its latter sections use Mexico to illustrate an ‘early’ interpretation of Latin America's Cold War which emphasizes the under-appreciated importance of the 1940s and the significance of longer-term continuities.

I

We begin with the question of definition. This seems, on the face of it, alluringly straightforward. Most of us, after all, think we know what the Cold War was more generally, so ought we not just find its manifestations in Latin America and fold them into broader narratives? The Cuban Revolution and attempts to defeat it; Allende's government and Pinochet's coup; the Sandinistas’ victory in Nicaragua: these all feel unequivocally like Cold War events or processes. Yet things get murkier when we think about the Brazilian military coup of 1964, or the US invasion of the Dominican Republic in 1965. Were the Costa Rican civil war and the Colombian Bogotazo of 1948 Cold War conflicts? And looking beyond the received wisdom of leftist narcosis in 1950s Latin America, we find a panoply of ideas, movements, and parties which intersect with the broader global conflict in awkward and surprising ways.Footnote 7 With just a little interrogation, all that is solid melts into air.

In what remains the most rigorous effort to address these issues of definition, Tanya Harmer has offered four qualifications. The first is that the adjective ‘cold’ is inappropriate in our context: Latin America's conflicts ‘left hundreds of thousands dead, tortured or disappeared, forced millions into exile and yet millions more to change their way of life’.Footnote 8 As a corollary, ‘war’ might not be much use either, for while ‘there was violence on all sides, more often than not it was the state that carried out the majority of this violence’.Footnote 9 Harmer's second point is that, in sharp contrast to Europe and several other regions, ‘revolution and counter-revolution characterized the Cold War’ here. Third, this was a complicated and internationalized conflict: ‘events in one country had an impact across the region’. And finally, US ‘intervention’ ‘underpinned’ Latin American's Cold War.Footnote 10 This builds upon Greg Grandin's assertion that ‘what most joined Latin America's insurgencies, revolutions, and counterrevolutions into an amalgamated and definable historical event was the shared structural position of subordination each nation in the region had to the United States’.Footnote 11 These specificities have increasingly led scholars to speak of Latin America's Cold War rather than of the Cold War in Latin America, treating it as a distinctive regional event with its own particular dynamics, and not just another iteration of a global conflict driven by superpower rivalry.Footnote 12 Recent scholarship, such as the work of Harmer, Grandin and Gilbert Joseph, and Daniela Spenser, has also urged us to think of the ‘long Cold War’, a protracted conflict with its origins well before the 1954 Guatemalan coup or the 1959 Cuban Revolution.Footnote 13

In response to this call to consider the longue durée, I suggest that we should take a geological approach to Latin America's Cold War. This reveals several stacked layers of conflict. While some very much bring to mind an Atlanticist vision of the mid- to late twentieth-century Cold War (capital C, capital W) – capitalism versus socialism, for instance, and the contraposition of US- and USSR-led blocs – others are much older, and have far less (if anything at all) to do with a Washington–Moscow bipolarity. For how can we think about Guatemalan, Cuban, Chilean, or Nicaraguan attempts at revolution without factoring in long-standing tensions between landowner and peasant and state and citizen, or between the US quest for pseudo-imperial hegemony and local assertions of national sovereignty? While different conflicts stacked up over time, all were, in one way or another, struggles over the mode of economic production whose origins long predated Latin America's Cold War. It is clear that this conflict did not begin in 1492, 1810, or 1898. Some of its major constituent parts, however, did. The processes and structures which gave this conflict its own set of unique conditions are mostly very old indeed.Footnote 14 It is thus fair to cast the new alignments and conflicts of Latin America's Cold War as a new and distinct phase in a much longer bundle of struggles for control of the region's population, land, and natural resources. This new phase, it would appear, began not in the late 1950s, but a decade earlier, in the 1940s. Explanations which overlook 1917, 1948, and 1959 as linked points in an escalating pattern of regional conflict are thus likely too narrow in temporal focus, just as are those that set aside pre-1917 structures of property rights, empire, citizenship, race, gender, and labour.

Those seeking to assert control over Latin America's resources were, after the region's opening to US capital in the later nineteenth century, almost always an – often asymmetrical – alliance between local elites and US interests. As Greg Grandin argued early this century in an excoriating critique of the ‘myopic obsession[s]’ of diplomatic history and grand abstractions of new left revisionism, ‘in nearly every…nation the conflict that emerged in the immediate period after World War II between the promise of reform and efforts taken to contain that promise profoundly influenced the particular shape of Cold War politics in each country’.Footnote 15 For Grandin, as for other scholars of the time, Latin America's Cold War was a complex and multi-scalar conflict driven not just by transregional and regional processes, but also by the way they interacted with particular national and sub-national trajectories. There is little room here for what Gilbert Joseph has described as the ‘veritable obsession with first causes, with blame, and with the motives and roles of US policy-makers [which] often served to join realist historians and the New Left Revisionist critics at the hip’.Footnote 16

Though coming from a rather different standpoint, Max Paul Friedman also called for greater attention to ‘Latin American agency’, making a persuasive case for foregrounding local power structures and elite actions and retreating from the reflexive assignation of both blame and ultimate power upon the United States.Footnote 17 For, as noted below, it is the recurring entanglement of local repressive elites with the United States which made for such a powerful combination.Footnote 18 American support made the former ‘especially intransigent in defending their privileges while discrediting them further to nationalist reform movements’, even as they retained the ability ‘to distort local conflicts even further than U.S. “hegemons” wished them to’.Footnote 19 Despite these arguments’ weight, an older received wisdom persists in some quarters.Footnote 20

II

Indeed, it remains the case that Latin America is still largely overlooked as a site of Cold War conflict – especially prior to the 1959 Cuban Revolution. Though this is changing, much greater attention has been paid over the last two decades to conflicts in Asia and Africa.Footnote 21 And while scholars have recently conceded the importance of the Guatemalan coup of 1954, there remains a broad narrative of ‘lateness’.Footnote 22 Key contributions such as the three-volume Cambridge history of the Cold War relegate pre-1959 Latin America to just a few paragraphs – sometimes, and uncomfortably, as a footnote to narratives of decolonization.Footnote 23 Similarly, popular histories like those of Ian Buruma and Victor Sebestyen entirely omit the region perpetuating the idea that the Cold War simply had not arrived there yet.Footnote 24 When scholars do examine the region, it is often through the lens of US–USSR conflict, tracing what Jürgen Buchenau has described as ‘the loud repercussions of international conflict’.Footnote 25 This is an awkward fit, for as Tanya Harmer has argued, this was not a ‘bipolar superpower struggle projected from outside’, but a ‘unique and multisided contest between regional proponents of communism’ – to whom we can add economic nationalists and perceived communists – and advocates of capitalism.Footnote 26

There are important exceptions to this trend. Leslie Bethell and Ian Roxborough have argued that the Cold War began in Latin America in 1948, while Darlene Rivas has made the case that the 1947 Rio Pact and the creation in 1948 of the Organization of American States ‘were…a product of the Cold War and US efforts to protect the hemisphere from “Soviet” communism’ – though with the qualifier that ‘their origins were in Latin American attempts to contain the United States and to provide a means for collective…action’.Footnote 27 In their work, the US–USSR conflict is thus overlaid on an existing tension between national sovereignty and US influence, with anti-communism papering over the cracks. At a more general level sits Odd Arne Westad's latest work, which aims to drag us out of the George Kennan world in which we have all been living. In many ways, Westad's book marks a welcome departure within scholarship on the ‘global Cold War’. It notes the deep roots of conflict in Latin America, dating back to the nineteenth century and the supplanting of British economic dominance by that of the United States. It explicitly makes the case for the 1920s and 1930s as part of the same battle as later struggles with which we are more familiar. And it also makes clear that the Cold War wove an international conflict – or, rather, an aggregation of US offensives, whether economic, diplomatic, or military – with long-standing domestic tensions over class, ethnicity, and nationalism. Going further, Westad wonders whether ‘the roots of the Latin American Cold War fed on high levels of inequality and social oppression’. In describing the violence of the late Cold War, Westad notes that its victims were mostly ‘labor organizers, journalists, student leaders, or human rights activists’, not doctrinaire leftists. This resonates with one of this article's central claims: Cold Warriors of the classic ’45–’89 vintage folded in a series of long-standing grievances and conflicts under the totalizing banner of anti-communism. And yet a note of criticism can be struck. Like Friedman, Westad concludes that ‘the United States did not have subservient ideological allies in power in Latin America’. This is true – and Westad is certainly correct that ‘a Betancourt, a Barrientos, or even otherwise despicable creatures such as a Videla or a Pinochet, were not straw men for the United States’.Footnote 28 But does this really matter, when both sides shared the same enemies? In the end, the apocryphal ‘our son of a bitch’ foreign policy dominated.

Despite such works, the years between 1945 and 1954, in particular, are overlooked. There are two reasons for this neglect. Far from suggesting an absence of Cold War context, both can be seen as results or symptoms of the Cold War. The first is that the Second World War weakened Communist party ties to the Soviet Union. The relationship between the Comintern and Latin American communists had been ambivalent for some time.Footnote 29 And though Soviet interest did not disappear entirely, it goes without saying that an under-resourced and under-informed USSR had higher priorities elsewhere. This renders the region relatively uninteresting for those who think of the Cold War as a bipolar superpower conflict.Footnote 30 While Soviet interest in the region eventually (re-)grew, sensitivity to regional specificity did not: Moscow remained markedly nervous of talk of revolution, as did many orthodox communists, particularly in northern Latin America.

The second is that Latin America's leftist parties were, with few exceptions, in retreat from 1948 onwards.Footnote 31 In some cases – Mexico, Brazil, Argentina – this happened rather earlier. Many communist parties split, saw precipitous declines in membership, and even went underground. The Mexican Communist party, for instance, collaborated in its own oppression to a quite remarkable extent, but the difference between its treatment by Lázaro Cárdenas in the mid-1930s and Miguel Alemán in the late 1940s is striking.Footnote 32 There were local ideological and geopolitical reasons for these shifting fortunes, but the shift, after the Rio Treaty, towards anti-communist domestic policy across much of Latin America was vital – doubly so after the outbreak of the Korean War.

What we are left with, then, is a period of US geopolitical dominance and anti-communism in most local political contexts. The impression given by the breakdown of negotiations over a hemispheric economic settlement was that the United States was in some way ignoring Latin America, but as Steve Niblo put it, this was an ‘indifference based on supremacy’.Footnote 33 By the late 1940s, the argument had been won. In many ways, this was the first battlefield of the post-1945 Cold War for the US, and it was one which brought a swift victory. Under the terms of this victory, ‘the donkey work of “containment” [was] largely undertaken by Latin American elites, while the principal costs [were] borne by Latin American societies’.Footnote 34 The lack of ongoing, large-scale conflict between ‘communist’ and ‘anti-communist’ forces, however, should not exclude this period from Cold War narratives. Rather, the successful outsourcing of anti-communism between 1945 and the Guatemalan coup should be seen as one chapter in that narrative.

Thus, as Stephen Rabe suggests, Eisenhower's charge that Truman had no policy for Latin America was an over-reach. While their emphases were different, both presidents used various means at their disposal to ‘wage cold war’ in or through the region.Footnote 35 Truman's decision to work with dictators and to favour ‘security concerns’, whether it ‘frustrat[ed], demoraliz[ed], [or] even radicaliz[ed] Latin American progressives’, ultimately served Cold War grand strategy.Footnote 36 Peter Smith concurs, seeing 1950 as ‘a turning point in American attitudes toward the region’ with the National Security Council memorandum on ‘Inter-American military collaboration’ bringing significant military aid, regardless of the nature of the recipient government. The United States’ over-riding consideration throughout this period remained the securing of regional allies to confront global communism. Grandin is surely right that ‘it was on Kennedy's watch that the United States, building on hemispheric military relations established during World War II, helped lay the material and ideological foundations for subsequent Latin American terror states’.Footnote 37 But regional political elites’ receptiveness had its roots in the 1940s in Mexico, the 1930s in Brazil, El Salvador, or Nicaragua, or even earlier in Chile and Argentina. Though the Castroist challenge quickened the pace of conflict, its fundaments were already in place.

Those local and regional studies that have emerged have acquired a magnified significance to our understanding of both the importance of the Cold War for Latin America and the importance of Latin America for the Cold War. One cannot overlook, for instance, the impact of Aaron Coy Moulton's work, which has recentred the conversation around the Caribbean Basin. In a series of articles, Moulton has cemented the idea of the region as its ‘own backyard’, crafting a careful balance between broader structures and local agency in the region. Luis Trejos Rosero has made a similar case for a rather different set of structures and agents in Colombia – again bringing together a raft of older conflicts under the unifying banner of ‘anti-communism’ – as has Marcelo Casals for Chile.Footnote 38 In similar fashion, Robert A. Karl's recent work has revealed both the need to delve deeper into local dynamics, and the difficulty of inserting these patterns into broader narratives. His account of Colombia's ‘forgotten peace’ is an exemplary piece of scholarship, combining tremendous research with a healthy scepticism for received truths and a keen sensitivity for his subject's ongoing relevance.Footnote 39 While this essay largely focuses on problematizing the Cold War's beginning in the region, Karl's work reminds us that pinpointing its end can be just as tricky. But it is also a reminder of the need to account for particularities, both national and sub-national. When we consider the immanence of the peace–violence dyad across Colombia's modern history, attempts to insert the country into a grand supra-national narrative may seem entirely quixotic. More than this, the specificities of local conflicts and processes – around peace and citizenship in particular – render even a national approach deeply problematic. Here one might draw parallels with Alexander Aviña's work on the Mexican state of Guerrero.Footnote 40 Just as importantly, Karl shows that conflict over land, the contested nature of citizenship, engagement with the law, and relationships with ideas and ideology are all complicated and interwoven.Footnote 41

III

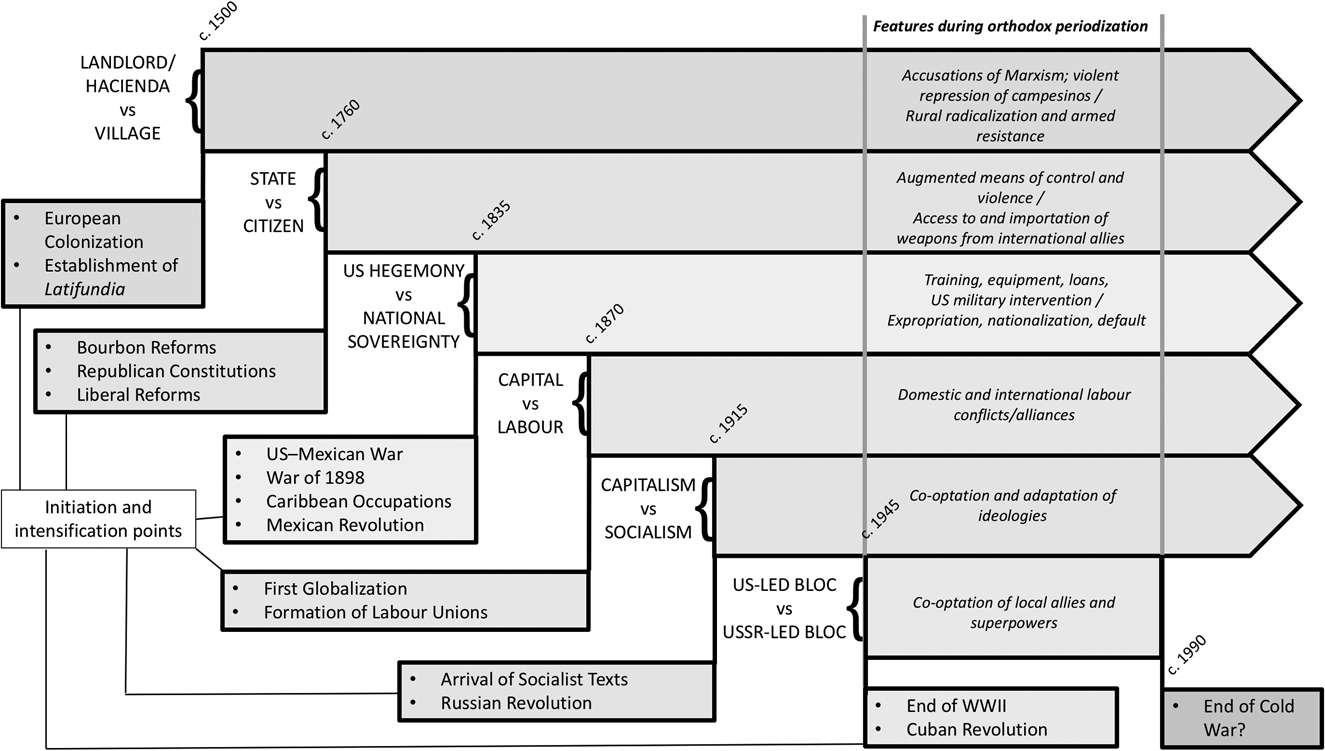

Perhaps the best way to think about this complex skein of conflicts is to see it as a set of layers (see Figure 1). In doing so, I build on the work of Greg Grandin, who pointed in a groundbreaking 2004 study to three interwoven struggles that defined Latin America's Cold War: a local left–right conflict, into which the US either inserted itself or was invited; a wider battle between social democratic norms and a deeply conservative, often murderously racist authoritarianism; and, broadest of all, the (by then) almost two-hundred-year-old confrontation between enlightenment and counter-enlightenment.Footnote 42 This interweaving gave Latin American conflicts a heterodox, patchwork nature that ideological frameworks birthed in the global north-west have continually struggled to integrate. As Corey Robin put it, ‘the entire continent was fired by a combination of Karl Marx, the Declaration of Independence and Walt Whitman.’Footnote 43 Even the term ‘left–right conflict’ must be used with caution, as a cursory reading of the Costa Rican civil war, for instance, makes abundantly clear. Thus, though I borrow Grandin's organizing principle of layers, I propose going rather further, and suggest six layers of conflict: between landowner and peasant; state and citizen; US hegemony and national sovereignty; capital and labour; capitalism and socialism; and, finally, between a US-led bloc and a USSR-led bloc.

Fig 1. The Cold War as a ‘layered stack’ of Latin American conflicts

The first layer to consider is that of the long-standing conflict between landowners and peasants – and between the region's latifundias or haciendas and its villages. While imperial rule and slavery were present in the pre-colonial Americas, European conquest folded multiple political and economic repressions into a fairly unified (albeit uneven) system. As the initial encomienda tribute system gave way to the more procrustean repartimiento, the infamous latifundia, large rural estates characterized by unfree labour, were constructed. In many areas, political economy came to be defined by the hacienda–village dyad, a symbiotic – if asymmetric – mechanism for extracting resources and exercising power. This relationship continued to define most of rural Latin America – until the late twentieth century home for the majority of the region's population – throughout colonial times and into the national period. Relationships between hacienda and village, and more generally between landowner and peasant, embedded norms around race, gender, land, and labour – some of which still persist – which were certainly important local determinants of Cold War era conflicts. As Knight has shown for late nineteenth-century Mexico, in areas where the hacienda–village relationship remained important, it acted as a potential brake on local capitalist development, relying as it did ‘on combinations of coercion, corporal punishment, monopoly of land, “paternalism”, and political backup’.Footnote 44 Victor Figueroa Clark, meanwhile, reminds us that we must leave Eurocentric assumptions about peasants and landlords at the Atlantic shore. ‘Although the campesinos lived in conditions that bore a superficial resemblance to feudal structures’, he writes, ‘they were also often indigenous and therefore held a different worldview, particularly toward private property and the land’. As for the bourgeoisie, ‘[o]utside the Southern Cone…rather than being a productive capitalist class, [it] tended to be dependent upon large foreign-owned enterprises and foreign capital’.Footnote 45

This lends weight to the contention that, where these socio-economic structures persisted, the systemic struggle between capitalism and communism central to certain interpretations of the Cold War is inherently limited in relevance. Mid-twentieth-century capitalists, like mid-nineteenth-century Liberals, often wished to ‘unlock’ the potential profit of these seemingly feudal institutions rather than intervene to preserve unwaged, unfree labour, while many communists overlooked rural and/or indigenous labour regimes as pre-capitalist, and therefore politically irrelevant – a position considerably easier to maintain when fortified with prejudices of racial hierarchy and urban superiority. Thus, the label of ‘progressive’ or ‘reformer’ is not easily applied.Footnote 46 By contrast, hacendados – on the whole authoritarian, conservative, and white – and their military allies used Cold War conflicts as a means of strengthening or re-establishing paternalistic, repressive, often violently abusive, and even genocidal dominance over rural villagers.Footnote 47 This was understood and – naturally – used as propaganda by the left; Che Guevara notably identified ‘the permanent roots of all social phenomena in America’ as ‘the latifundia system, underdevelopment and “the hunger of the people”’.Footnote 48 This takes us all the way back to Bartolomé de Las Casas, who sounded positively Kolkoesque even in 1561, writing that ‘our work was to exasperate, ravage, kill, mangle and destroy; small wonder, then, if they tried to kill one of us now and then’.Footnote 49

The second long-standing conflict is between the state, an entity which developed and mutated in particular phases – notably under the Bourbon Reforms of the 1760s, the creation of republican constitutions in the independence period, and liberal reforms in the mid- to late nineteenth century – and its putative citizens.Footnote 50 Timo Schaefer neatly sums up the developments – formalizations is perhaps a better word – that took place during the nineteenth century in his survey of legal cultures in post-independence Mexico. This was a period, he writes, which ‘began with the Declaration of the Rights of Man and ended with the triumph of new class- and race-based hierarchies’.Footnote 51 In a similar vein, Elizabeth Dore has demonstrated persuasively that for women, nineteenth-century liberalism represented ‘one step forward [and] two steps back’.Footnote 52 This transformation did not happen in a political vacuum. To quote Schaefer again, ‘any vestige of the liberal ideal collapsed in the second half of the century under the pressure of economic modernization schemes premised on elite control over indigenous land and labor’.Footnote 53 It is important to stress, then, that the legal-constitutional process by which colonial subjects passed through a contested and unevenly experienced period of revolutionary semi-autonomy to become frequently oppressed subjects of modernizing republics happened – for most of the region – before the shift to domestic capitalism was complete – if, indeed, it is.

Some parts of this process, particularly the formalization of unfree labour regimes in majority-indigenous areas, represented returns to pre-existing conflicts. Others – including the hollowing-out of individual and communal rights in the face of novel, aggressively enforced conceptions of property – were new, or at least given new vitality by the means available to a late nineteenth-century state. And none went away: in all of our ‘definitive’ Cold War conflicts, personal or communal rights faced off against private or blended elite interests, while race and class informed battles over ongoing labour exploitation. Crucial to this model, I think, is Schaefer's notion of ‘revolutionary liberalism’. The simple idea of equal treatment before the law is fundamental in so many manifestations of Latin America's Cold War; its frequent denial underpinned myriad grievances.

Schaefer concludes that three kinds of legal manipulation – whether the creation of legal exceptions or elite interference with the law – developed in late nineteenth-century Mexico. The first comprised attempts to deny townspeople – often, but not always, mestizo, not usually well-off, but with a good working legal-constitutional knowledge – the ‘full exercise of their legal rights guaranteed by successive Mexican constitutions’.Footnote 54 The second was the blurring of lines between private and public roles such that wealth (often, though not only, meaning landownership) brought with it the assumption of pseudo-legal-constitutional roles in census-taking, policing, and the definition or transference of property rights. The net result was ‘a creeping privatisation of law’ which naturally favoured the class holding the gavel. The third was the fact that while, formally, the repressive apparatuses of state were embedded in the legal-constitutional order, both de facto ‘concrete institutional arrangements’ and the collective belief of Mexicans in general reveal the existence of armed forces operating outside the law.Footnote 55

In each of these three areas, the conflict between state and citizen – which sometimes mapped onto that between ‘the elite’ and ‘the people’ – would have ruinous Cold War consequences. Bolstered by modern military training, equipment, and materiel, a colonial-era zealotry on matters of race, and the US's implicit backing, it was states that ultimately prosecuted the Cold War in Latin America. In McPherson's words: ‘the overwhelming…burden of the violence should be attributed to conservative military states’.Footnote 56 As Grandin's account of the Panzós massacre in Guatemala, in which ‘between five hundred and seven hundred Q'eqchi’-Mayan women, men, and children’ were killed, suggests, ordinary people were aware of their rights and theoretical means of recourse, but a combination of ‘privatised law’ and ‘armed forces operating outside the law’ prevented such recourse, by hook or by crook. Schaefer's ideas thus have application far beyond nineteenth-century Mexico.

The next dyad to consider is that of US hegemony and national sovereignty. Caitlin Fitz has demonstrated the shift in US political culture from ‘the idea of a united republican hemisphere’ towards one of superiority and ‘rightful’ dominance.Footnote 57 While for Fitz the intellectual change occurred in the 1820s, its most obvious practical unveiling was in the US–Mexican War two decades later. Having provoked Mexico into military conflict, President Polk had no qualms about placing the blame on the United States’ southern neighbour, insisting ‘we are called upon by every consideration of duty and patriotism to vindicate with decision the honor, the rights, and the interests of our country’.Footnote 58 The framing of a war of conquest as springing from ‘duty and patriotism’ is important, and the precise nature of that duty and patriotism in the 1840s bears closer examination as it frames many later interventions.Footnote 59 This war came shortly after journalist John L. O'Sullivan coined the idea of manifest destiny, asserting that the United States was free ‘to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions’.Footnote 60 What followed – filibustering, occupations, imposition of leaders – revealed a conflict within Latin America's polities – and, at times, its elites – between those urging national sovereignty, whether in a diplomatic or economic sense, though the latter is conceptually slippery, and those urging co-operation – or, for opponents, collaboration – with the US. In vulgar terms, this was a struggle between – often nationalist – anti-imperialism and – often comprador – colonialism, with the latter finding encouragement and support in a US with a very clear sense of its ‘own’ backyard.

During Latin America's Cold War, the banner of anti-imperialism was wafted rather feebly by the Soviet Union (and to a degree China), but the most notable promoter and corraller of Latin American national liberation movements was Cuba. This purposing of national liberation as the left position necessitated a folding of non-communist figures such as José Martí and Augusto Sandino into doctrinaire revolutionary narratives, marking the Cold War as a new, albeit relatively distinct, phase in another older conflict. However, this fracture could be subsumed within, or subordinated to, other conjunctural priorities. Thus, Mexico's economic nationalism – particularly in the petroleum sector – was tolerated for many decades, outweighed by the solidity of the government's anti-communism and the lack of serious challenge to either capitalism or to US regional dominance.Footnote 61 That said, it is worth at least considering whether the additional pressure of the final layer – the formalized US–USSR conflict and the muscular and ill-informed anti-communism it fostered – would have prevented a cardenista politics being tolerated by the United States after 1945. The panic induced in diplomatic correspondence over the National Liberation Movement in 1961 suggests so.Footnote 62

In a recent essay, Stuart Schrader makes a compelling case for seeing US–Latin American relations since 1898 as a ‘Long counterrevolution’.Footnote 63 Schrader suggests ‘the persistence of a strong relationship between security objectives and political economy’, reminding us that the heuristic distinction between conflicts over sovereignty and those between capital and labour is always somewhat artificial. Indeed, ‘US security assistance in the region…was marked by sovereignty's abrogation’, and its economic policy by a twin commitment to fostering ‘the most basic forms of economic development while also repressing revolutionary movements that might rebel against the prevailing socioeconomic order’.Footnote 64 This was evident – if unevenly so – during the early Cold War, just as it was in earlier decades. Daniel Immerwahr's recent How to hide an empire reminds us that ‘empire might be hard to make out from the mainland, but from the sites of colonial rule themselves, it's impossible to miss’. Even absent formal colonization, ‘clearly this is not a country that keeps its hands to itself’.Footnote 65 A final note of caution here: national sovereignty is just as slippery a concept as hegemony or imperialism. While diplomats could agree on a common principle of ‘non-intervention’ in theory, there are enough instances of elite factions inviting or facilitating intervention, or other less dramatic breaches of ‘sovereignty’, as to render the principle problematic at best, and meaningless at worst. To return to an earlier point, Latin America has never lacked elite actors ready to amplify or leverage their strength by calling upon US resources.

With the onset of capitalism in the region comes another layer of conflict – that between capital and labour. Here, though, is one of the thorniest sites of contention in both political economy and historiography; the question of when Latin America was capitalist is even more vexed than that of the timing and nature of its Cold War. The problem lies not so much in the realm of capital as it does in that of labour. For various reasons, not least the institutions and mechanisms introduced by European occupiers, there were severe distortions in the labour market, which is a way of saying that many (usually indigenous) Latin Americans were set to work in conditions which approximated – both at the time and in hindsight – to slavery.Footnote 66 While critics may have exaggerated – or rather over-generalized – the ‘black legend’ of indebted peonage, its existence – and, a fortiori, that of ‘voluntary peonage’ – throws a significant spanner in any Marxian efforts to locate incipient markets.Footnote 67 This is apparent from a plethora of cases, not least recent work such as that of Casey Lurtz on the integration of Chiapas and its coffee-growing economy into the capitalist circuit by 1920, or Andrew Torget's study of the Texas borderlands.Footnote 68 There are, of course, studies of Latin American labour which feel more familiar to a (globally) north-western audience. While still attentive to local specificities, the works of Ernesto Semán and Paulo Drinot offer fruitful comparisons with those on, say, Italian or US labour.Footnote 69

Yet it is important to recognize that the onset of Latin America's capital–labour conflicts took place – broadly – many decades, and in some places, a century, before it was defined by the dichotomy of capitalism and socialism. This dislocation was far more dramatic than the lag between, say, continental European industrialization and the growth of socialist ideology and organizations.Footnote 70 While versions of the capital–labour conflict had been playing out across the region throughout the later nineteenth century, the framing of a distinct, though closely associated, conflict – of capitalism against socialism (and/or, in many areas, anarchism) emerged more fitfully as leftist ideas arrived via oral, textual, and organizational transmission. Both Marxism and anarchism arrived and spread in Latin America in the second half of the nineteenth century, though there were some Fourierist interlopers as early as the 1840s. These ideologies put down roots, syncretizing in places and dogmatizing in others, and provoked the ire of both elites and populist or nationalist alternatives.Footnote 71 Without this endogenous oppositional lineage, the anti-communism of the 1940s and 1950s could not have expanded so easily. That said, the rapid growth of support for socialist ideas in general, and membership of communist organizations in particular, no doubt stiffened opponents’ resolve. Between 1935 and 1947, aggregate Communist party membership in Latin America is estimated to have grown from 25,000 to 500,000.Footnote 72

Counter-mobilization was swift. Paulo Drinot has shown that a ‘creole anti-communism’ was securely in place in Peru by the mid-1930s; Mexico made a similar institutional turn a few years later.Footnote 73 By the mid-1940s, it was clear that the US had begun to overtly ‘encourage and reward’ communism's opponents.Footnote 74 Anti-communism had a devastating effect. As Figueroa Clark puts it, ‘[w]hile the repression of subaltern challenges…was not new, and while communists were not the only targets, their presence in all of the key…moments of conflict combined with elite fear of communism to ensure that communists were particularly hard hit by repression’.Footnote 75

The historiography bears testament to the amplitude of this conflict. While many anti-communist Latin Americans, like the Montoneros and their rallying cry of ‘a socialist country without Yankees or Marxists’ have insisted upon an anti-Marxist socialism often combining radicalism and nationalism, both historical actors and scholars have embraced the simple dichotomy of ‘The’ Cold War. As Patrick Iber has noted recently: ‘to simplify enormous and complex bodies of scholarship to their barest essences, orthodoxy held communism primarily responsible, while revisionism blamed capitalism’.Footnote 76 And yet we should keep in mind that ‘the politics and culture of anti-communism cannot be divorced in any meaningful way from the political economy of the Cold War’.Footnote 77 More broadly, the temporal consonance of ‘Latin America's efforts to overcome its inequitable and stunted development and the United States’ rise, first to hemispheric and then to global hegemony’ contributed to shaping a ‘century of revolution’, a long Cold War in which the conflict between ‘reds’ and ‘whites’ was a consistent thread.Footnote 78 In a more direct fashion, Pettinà synthesizes recent historiography on this dichotomy, it – problematically – seeing ‘the Cold War principally as a dispute between two competing visions of modernity: capitalist and socialist’.Footnote 79 While this layer of conflict is certainly important, I agree that to place it above all other factors is to obscure variance over both time and space.

Finally we arrive at the geopolitical conflict many generalists would consider the bona fide Cold War – that in which the United States and its allies engaged, against a bloc of nations led by the Soviet Union. However, we are immediately forced to problematize this binary, as no Latin American nations were formally associated with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The Soviet Union, in particular, was ‘more of an active bystander than a main participant’.Footnote 80 In Latin America – with the exception of Cuba – this conflict was contingent, illusory even. Affiliations to or affinities with the Soviet bloc were often tenuous, particularly for subnational manifestations of the armed left, various incarnations of which drew upon pre-1945 traditions and organizations. Such affinities are also complicated by ‘south–south’ relationships, most notably in the case of Cuban support for anti-colonial struggles in Africa.Footnote 81

I am therefore not sure I would go quite as far as Gabriel García Marquez, who claimed in 1982 that ‘superpowers and other outsiders have fought over us for centuries in ways that have nothing to do with our problems’.Footnote 82 The Cold War powers did try to fold Latin America's problems into their conflict. However, the only coherent consonances that did exist were between some Latin American elites and some parts of the US state apparatus. As I have suggested, these pre-dated the Cold War, but were re-badged, beefed up, and made more Manichean from the late 1940s. As Grandin suggests, local ideological concerns came together in this period with global geopolitical considerations, with baleful effects: ‘in many countries the promise of a postwar social democratic nation was countered by the creation of a Cold War counterinsurgent terror state’.Footnote 83 Socio-economic demands born out of local structural conditions but encouraged by a wider democratic moment were opposed by existing elites augmenting their pre-Cold War strength with new methods and technologies, new allies, and a more coherent ideology.

This ‘layered stack’ model is designed to provoke discussion, and will necessarily need modification and augmentation. Four areas already seem to demand further interrogation, though perhaps as contextual factors rather than separate axes of conflict. Race, its conceptions, and its hierarchies, are woven inextricably into Latin America's political economy. The conflict outlined between landowner and peasant is, almost everywhere throughout the region, profoundly racialized, though with significant variation between Mexico, Central America, the Andes, Brazil, the Caribbean, and southern South America.Footnote 84 Moreover, racial thought has shaped access to labour markets, geographical mobility, and remuneration. Racial preconceptions were not the preserve of the right: long-standing leftist befuddlement with indigeneity and autonomy had profound effects in our period.Footnote 85 Furthermore, while racialized slavery as such was essentially outlawed across the region by the end of the nineteenth century, its legacy lived on throughout the Cold War, not least in the persistent repression and marginalization of Afro-Latino communities.

Alongside race must be considered gender. Latin America's Cold War had distinctly gendered facets, many in place before the Second World War. These are teased out in studies such as Elizabeth Quay Hutchison's account of domestic workers’ shifting political solidarities in Cold War Chile, or Margaret Power's analysis of the 1964 Chilean election, in which long-standing social attitudes rooted in religion and class were repurposed, the anti-communism being old, but nimble. In similar fashion, Benjamin Cowan has traced the roots of Brazil's Cold War gender politics to the Vargas era, Isabella Cosse has foregrounded the nineteenth-century roots of ‘a family type based on the indissolubility of marriage, gender inequality, and patriarchal power’ for Argentine Cold War guerrilleras, and Michelle Chase has examined Cuban women's revolutionary agency both before and after 1959.Footnote 86

While the literature on religious change and conflict in Latin America remains somewhat fissiparous, possibly reflecting its subject matter, divisions between – very broadly – conservative Catholic hierarchies and grassroots radicalism and, latterly, the rise of evangelical Protestantism are now fairly well covered in the historiography. Whether they quite fall into the Chomskyian framing of a continental Cold War battle between liberation theology and CIA-funded Pentecostalism remains rather more contentious.Footnote 87 Nevertheless, the role of the Catholic right in underpinning vernacular pre-Cold War anti-communism is clear, as Romain Robinet has shown in his work on Mexican organizations like the Federal District Student Confederation and National Union of Catholic Students, established respectively in 1916 and 1931.Footnote 88

Finally, we cannot neglect violence and its growing historiographical prominence. The emergence of radical left-wing guerrilla groups and the development of better-educated, better-equipped militaries certainly pre-dates the orthodox periodization of the Cold War in many parts of Latin America. As McPherson put it: ‘much of the violence perpetrated in the Cold War was not necessarily of the Cold War’.Footnote 89 The 1930s, for instance, saw a plethora of such developments, with the growth of the Sandino- and Martí-led movements pitted in an asymmetric confrontation with militaries that were increasingly autonomous, not just of national states and elites, but after 1970, of the US. Stephen Neufield and Thom Rath have shown that military modernization stretches back into the pre-revolutionary and revolutionary periods respectively in the Mexican case, playing a crucial role in state formation; Erik Ching has traced similar developments for the case of El Salvador.Footnote 90 Another aspect of state formation – the dyadic tension between democracy and dictatorship – may also deserve special consideration. Though I remain uncomfortable with these as primary categories of organization, Bethell and Roxborough, McPherson, and many others make a strong case for thinking around this axis of conflict.Footnote 91

IV

I now turn to the Mexican case, and in particular the idea that Mexico's Cold War was delayed, or even absent. In 2010, Hal Brands made an implicit case for a late Cold War for Mexico, beginning only with the 1959 Cuban Revolution. Renata Keller took up this claim in 2014, making rather more persuasively the case that ‘in Mexico, the Cold War began when the Cuban Revolution intensified the pre-existing struggle over the legacy of the Mexican Revolution’.Footnote 92 To Keller, the contestation movements that emerged during the ‘early years of the global Cold War’ ‘were not yet connected to that geopolitical confrontation’, but ‘independent responses to specific conditions in Mexico’.Footnote 93

In arguing for the Cold War's late arrival, Brands and Keller concur with Bethell and Roxborough that ‘to the extent that US policy figured in the conservative restoration, it was as a matter of neglect and indifference, rather than pro-authoritarian intervention’.Footnote 94 Yet in Mexico, the US neither neglected nor was indifferent to the campaign, election and presidency of Alemán in 1945–6, On the contrary, it began by seeking reassurances that he was genuinely anti-communist and rapidly moved to cement good relations by arranging the first presidential visit since the Mexican–American War of 1846–8. In its wake, Alemán agreed to a substantial opening up of Mexico to US capital. The evisceration of the political left in 1945–7 was followed by the charrazo, the defeat of radical labour between 1948 and 1951.Footnote 95 In 1950, fearing that leftist opposition to his government might use primaries to infiltrate the Institutional Revolutionary Party, Alemán declared a ‘systematic anti-Communist campaign’ and outlawed primaries.Footnote 96 These processes – an ever closer relationship between the US and Mexican governments defined in opposition to the Soviet Union and under the rubric of the Rio Treaty, a populist anti-communism with charges of fifth column membership, an agreement to open the Mexican market to US capital and imports, and the repression of radical left opponents of such changes – cannot, I think, be conceived of separately from the Cold War. McPherson concurs, noting that ‘Latin America was fully engaged in Cold War-related ideology and violence for a full decade before the Cuban Revolution, if not earlier in places such as Mexico.’Footnote 97 Iber goes further still, arguing that ‘studies’ that begin with the Cuban Revolution are ‘at least ten if not forty years too late’.Footnote 98

We can push this claim beyond culture: the Cold War diplomatic and economic dances took place early, were settled quickly, and placed Mexico firmly at the side of the United States. As Niblo suggests, the alliance was clear by the time of the Bretton Woods conference of 1944.Footnote 99 Despite rumblings of official discontent about Guatemala in 1954, and statements – however insincere – of concern about US policy towards revolutionary Cuba, Mexico's geopolitical relationship to its northern neighbour was such that critical rhetoric could not escalate into the sort of direct opposition seen before the Second World War.Footnote 100 And yet, while Mexico's structural position was overdetermined, Christy Thornton's forthcoming monograph shows that Mexican officials used what means they had – primarily the promotion of multilateralism – to contain their northern neighbour's looming power.Footnote 101

Nevertheless, the Cold War was normalized by the mid-1950s. The charrazo had absterged supposedly communist elements from Mexican labour, and the covert oficialista anti-communism of the mid-1940s was now more explicit. Jaime Pensado has noted the anti-communist nature of attacks on student leaders during the 1956 strikes, which described them as ‘dangerous puppets’ of the ‘International Communist Party’ (sic).Footnote 102 Similarly, Renata Keller shows very clearly that the re-radicalized railway workers’ movement of 1958–9 was deliberately framed as being under Soviet control.Footnote 103 Of course, we can go back further, and it makes a great deal of sense to examine the degree to which regional anti-communism appeared in the wake of the Russian Revolution – and in some cases, earlier still. Here, Daniela Spenser's works provide an invaluable guide to the genesis and course of Latin America's ‘long Cold War’.Footnote 104

V

There is no doubt that for Latin America, the 1945–54 period falls under the contextual shade of the geopolitical Cold War. However, historians must go further and examine the local and ideological contexts. In the case of Mexico, a North American, anti-communist, anti-worker, pro-business alliance blossomed between Presidents Alemán and Truman. In the Caribbean Basin, Moulton's argument that anti-dictatorial and pro-dictatorial transnational networks made ‘their own Cold War’ seems incontestable, and fits neatly as an earlier chapter of Harmer's Inter-American Cold War.Footnote 105 For the region as a whole, the Rio Treaty of 1947 tied Latin American foreign policy to that of the US, implicitly pitting it against the USSR. My hope is that future synoptic accounts of the Cold War include a chapter – unpalatable though it may be – detailing local and international anti-communist forces’ successful prosecution of the early Cold War. The relative dearth of left-wing governments and the weakness of labour movements and guerrillas in this period has seemed to stem scholarly curiosity, but just because the ‘right’ side was winning does not mean that the Cold War was not happening. In 2013, McPherson urged scholars to ‘question our most basic findings, even the finding that the Cold War pervaded Latin America’.Footnote 106 For my part, I still believe it did. As the ‘layered stack’ model suggests, the Cold War streamlined, bludgeoned, and bundled together a panoply of other, older conflicts. But in the broadest sense, we can detect a headline-level clarity even when the most cursory local digging throws up all manner of uncomfortable oddities.