INTRODUCTION

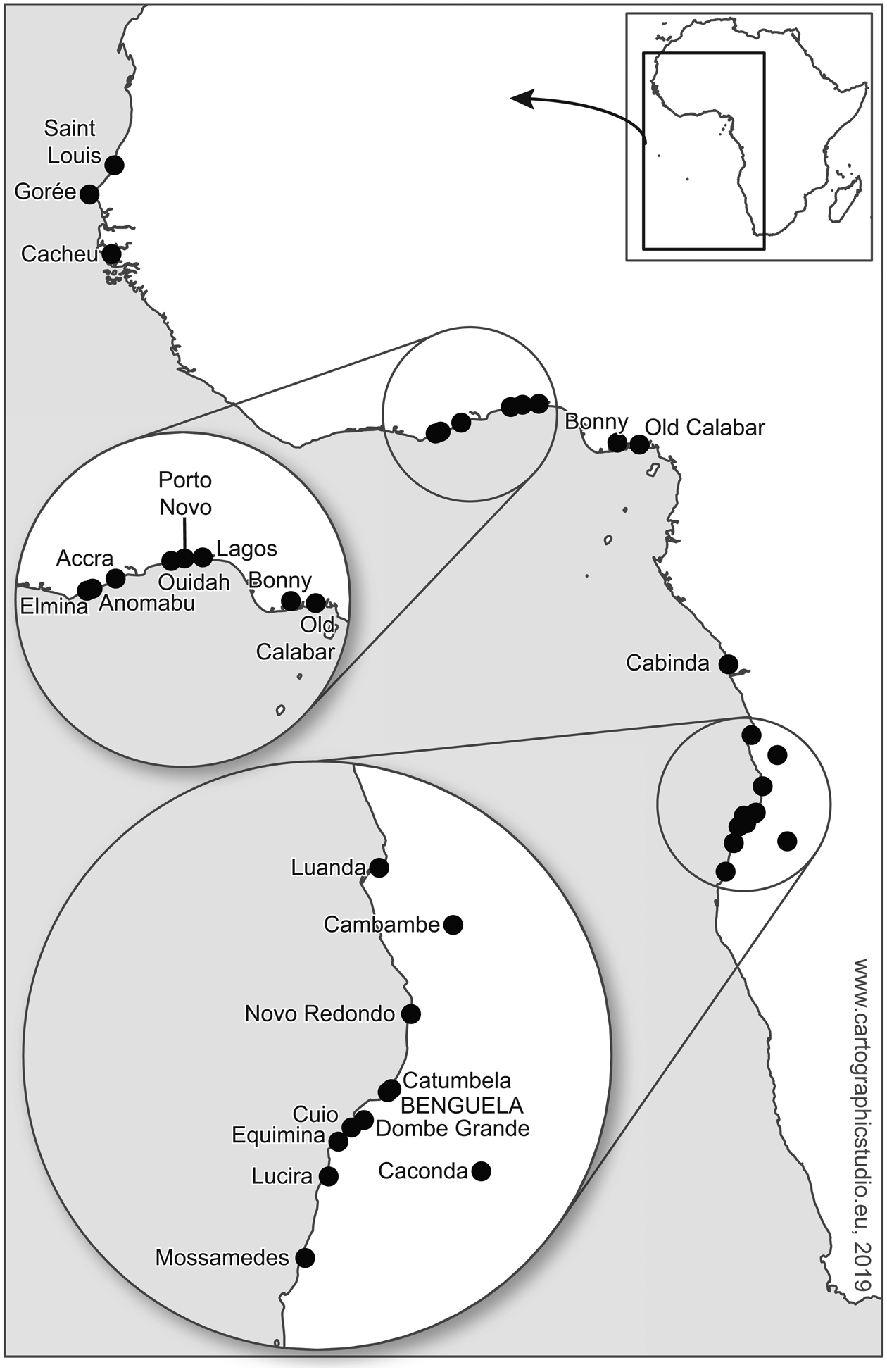

Urbanization and slavery have a long and intertwined history in West Central Africa and predate the early contact with Europeans in the late fifteenth century. Urban areas were located inland, away from the coast, yet they were important spaces of interaction and exchange, acting as political and economic centers.Footnote 1 With the expansion of the Atlantic world, smaller settlements along the African coast became important commercial centers and new towns emerged, linked to internal markets and European cities and ports in the Americas. These new towns included the ports of Saint Louis and Gorée in Senegambia; Elmina and Anomabu along the Gold Coast; Cacheu on the Upper Guinea Coast; Ouidah, Porto Novo, and Lagos in the Bight of Benin; Bonny and Old Calabar in the Bight of Biafra; and Luanda, Cabinda, and Benguela in West Central Africa.Footnote 2 The population of all these towns grew in the context of engagement with the Atlantic world and the expansion of the transatlantic slave trade. However, it is important to stress that urbanization in Africa predated the arrival of Europeans and the transatlantic slave trade, although further archeological research is necessary to provide more information on the nature and importance of West Central African urban centers.

In the era of Atlantic commerce, urban spaces on the African coast became centers of wealth concentration with the emergence of new commercial elites that profited from the sale of human beings along with ivory and gold. Several African ports had a sizable female population due to the pressures and dynamics of the slave trade but also the opportunities available in coastal towns. During the eighteenth century, population estimates indicate that women constituted the majority in coastal centers. For example, in the town of Cacheu on the Upper Guinea Coast there were 514 women and 386 men in 1731.Footnote 3 Luanda had 5,647 women and 4,108 men among its residents in 1781.Footnote 4 There were 1,352 women and 892 men in Benguela in 1797.Footnote 5 More information is available for port towns in the nineteenth century, as for the towns of Ouidah and Accra where women comprised the majority of the population.Footnote 6 Free and enslaved women played important economic roles in these coastal centers as traders, farmers, shopkeepers, and nurses, among other activities.Footnote 7 Similar to urban centers elsewhere along the Atlantic basin, slavery was central to the organization of the space and production of goods that attended populations in transit.Footnote 8 Unlike other ports on the African coast, in West Central Africa the expansion of slavery was also intimately linked to the consolidation of the Portuguese colonial establishment in Luanda, Benguela, and inland fortresses. The construction of colonial infrastructure, including administrative centers, fortresses, and ports, relied on the exploitation of unfree labor, as I have discussed elsewhere.Footnote 9

This study examines the expansion of slavery in Benguela during the nineteenth century. This period was a moment of profound transformation along the African coast, with the decline and abolition of slave exports as well as the expansion of slave labor in coastal and inland urban centers. Despite a historiography that celebrates the nineteenth century as the age of emancipation, liberty, and democratic revolutions, as framed by Robert Palmer, Eric Hobsbawm, and Janet Polasky, this study stresses the expansion and strengthening of the institution of slavery rather than its decline.Footnote 10 The eighteenth- and nineteenth-century liberal revolutions that swept the North Atlantic did not represent the end of African labor exploitation or even of slavery in West Central Africa. In fact, during the nineteenth century, slavery expanded in Luanda and Benguela as well as in other African urban centers, related to the transition to the so-called legitimate trade in natural resources such as ivory, and cash crops such as coffee, cocoa beans, and cotton.Footnote 11 Regaining, acquiring, or consolidating freedom became even more difficult for those who remained in bondage in West Central Africa. Individuals who petitioned for emancipation did not necessarily encounter supportive colonial officials or individuals who could help them in their quest for freedom.Footnote 12 In many ways, urban centers were not about opportunities and freedom but were threatening spaces. Several studies indicate that free Africans were kidnapped, enslaved, and deported to the Americas while conducting business, visiting friends or relatives, or transiting alone through coastal towns.Footnote 13

The Portuguese empire abolished slave exports from West Central Africa in 1836, yet the use of local enslaved people expanded after this date. Local merchants and recently arrived immigrants from Portugal and Brazil set up plantations around Benguela, making extensive use of unfree labor. Cotton and sugarcane plantations were established in order to meet international demand for raw materials in the context of industrialization. In urban centers such as Benguela, enslaved labor use also expanded until slavery was abolished in 1869, and a system of apprenticeship was put in place.Footnote 14 This process of the “slow death” of slavery has received some scholarly attention for other locations in Africa, but not much has been written about this transition in West Central Africa.Footnote 15 While in recent decades Roquinaldo Ferreira, Samuël Cöghe, Jelmer Vos, and Vanessa S. Oliveira have published important studies on the end of the slave trade and the expansion of unfree labor in commercial agriculture in Angola, much more research is needed, particularly regarding areas away from coastal centers and on the experiences of individuals in resisting forced labor.Footnote 16 In addition to exploring the expansion of slavery, this study examines the activities enslaved people performed and the nature of slave labor and resistance in Benguela. By looking at individual cases it is possible to interrogate the differences that existed in terms of gender, analyzing the type of labor performed by enslaved men and women, and how slavery changed over time. Relying on primary sources from the Arquivo Nacional de Angola, the Tribunal da Comarca de Benguela (both in Angola), and the Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (Portugal), this study discusses slavery in Benguela, helping us to analyze its meaning and limitations to the “age of liberty”, and slavery's direct relationship with colonialism on the African coast.Footnote 17

BENGUELA AND THE AGE OF ABOLITION

The nineteenth century was a period of profound transformations.Footnote 18 Although the French, American, and Saint Domingue revolutions led to the reorganization of states, economies, and labor in different spaces, it was not a period of liberty everywhere and to everyone in the Atlantic world.Footnote 19 The “universal cry of liberty”Footnote 20 did not reach West Central Africa until the end of the nineteenth century, and it certainly did not endorse political emancipation for Africans. In the colony of Angola, which also included the administration of the town of Benguela and its interior, arguments about slave exporting and its consequences for the stagnation of local agricultural production occupied some of the debate between metropolis and colony in the early decades of the nineteenth century. Different colonial authorities reported that the growing slave trade in the early nineteenth century affected the consolidation of agricultural production and local industries. In 1805, for example, the Catholic priest Boaventura José de Melo reported that the colonies of Benguela and Angola exported people who could produce food locally “due to the surplus of land and propitious environment”.Footnote 21 The governor of Angola in 1826, Nicolau Abreu Castelo Branco, personally encouraged the production of sugarcane to replace the export of captives, and recommended that the Portuguese Crown reward any trader engaged in new economic activities with an honorary induction into the Order of Christ.Footnote 22 The Portuguese empire envisioned exploiting the production of cotton and indigo in addition to sugarcane, but also tapping into natural resources such as beeswax, gum copal, and orchil lichen – products in high demand from industries in Europe and North America.Footnote 23 In all these industries coerced labor would respond to the demand for increased production.

Despite British pressure to bring the slave trade to an end and the progressive abolition of slavery in the Americas, there were protests that without enslavement it would be very difficult to maintain production since the local population was considered “unwilling to cooperate” and rebellious; it was claimed that the only way to obtain labor was through force and violence.Footnote 24 The debates about colonialism, agricultural expansion, and new economic plans after the 1836 slave export ban continued into the 1840s, despite the fact that the slave trade remained alive in part due to the demand in markets such as Cuba and Brazil. In 1844, José Joaquim Lopes de Lima, the colonial administrator in Goa and Timor, claimed “the infamous trade hurt our interest in Africa, stealing our hands who are employed in strange lands”, making reference to the use of African enslaved labor in Brazil.Footnote 25 Pamphlets and booklets were published to advance the idea that enslaved people should remain in West Central Africa to help consolidate Portuguese colonialism and agricultural production.Footnote 26 Projects were approved to financially support agricultural expansion, relying, ironically, on the labor of enslaved people. For example, the Projeto de Regulamento da Companhia de Agricultura e Indústria de Angola e Benguela (Project to Regulate the Agriculture and Industry Companies of Angola and Benguela) suggested shifting the focus from captive exports to a less lucrative though “noble” economic enterprise: the production of coffee, sugarcane, and natural resources within the Portuguese colonies in Africa.Footnote 27 In many ways, the 1836 slave export ban led to the expansion of slavery locally, similar to what happened elsewhere in the Atlantic world, and leading to what historians have called the second slavery period.Footnote 28 Plantations spread in Benguela and surrounding areas, such as Catumbela, Dombe Grande, and Cuio, as can be seen in Figure 1.Footnote 29

Figure 1. The Western African coast, with details to locations mentioned in the text.

In the 1850s, the newly appointed governor of Benguela, Vicente Ferrer Barruncho, was particularly interested in the development of a cash crop economy. In an 1856 report written a few months after his arrival in Benguela, he described the region of Dombe Grande as “excellent for agriculture. It could be even better if the heathens [gentio] were not so devoted to their customs and habits and neglectful of hard labor. […] All the flour consumed in Benguela comes from this location”. He observed that one example of prosperity was the Equimina farm, owned by Ignácio Teixeira Xavier, whom he described as an entrepreneur. In Equimina, Barruncho claimed, Teixeira Xavier

produced aguardente, but not sugar. […] Labor was employed in the production of manioc, potato and maize. […] I saw how the slaves are well employed and treated. Only 46 slaves were used, which included carpenters and a blacksmith. In the production of orchil lichen, 63 slaves are employed. In the coast town of Lucira, Teixeira Xavier employs 52 of his slaves in fishing.Footnote 30

The governor suggested that Benguela residents should follow Teixeira Xavier's business model, employing enslaved and free labor for the advancement of plantation agriculture.

Barruncho's suggestions conformed with Portuguese colonial policies. With the end of transatlantic slave exports, the Portuguese administration encouraged the diversification of the economy, favoring the export of local staples such as orchil lichen. However, Barruncho's model entrepreneur, Teixeira Xavier, was later accused of smuggling enslaved labor overseas and using his plantations as a façade for his illegal business. This case shows how legitimate commerce in raw materials and tropical goods developed hand in hand with the smuggling of human beings. The governor of Angola, José Sobrinho Coelho do Amaral, accused Barruncho of involvement in the illegal slaving scheme, suggesting that Teixeira Xavier's legal activity camouflaged contraband trade in slaves.Footnote 31 The trader John Monteiro, who visited Benguela a few years later, argued that “only a very large number of cruisers on the Angolan coast could have prevented the shipment of slaves, as every man and woman, white or black, was interested in the trade, and a perfect system of communication existed from all points, overland and by sea”.Footnote 32 Thus, the expansion of agricultural production in Benguela and elsewhere in West Central Africa was connected to the growth of enslaved labor locally and contraband trade in human beings.

Slavery expanded in public and private spaces, including in official economic and household activities, and continued to exist as a legal institution until 1869. However, individuals continued to be enslaved well into the 1870s. In 1873, for example, Bento Augusto Ribeiro Lopes seized two free women in Benguela and put them to work on his farm in Catumbela.Footnote 33 Although the practice had been officially abolished, individuals like Ribeiro Lopes enslaved people without fear of any reprehension, a clear indication that the age of abolition had not reached West Central Africa, and Benguela in particular.

THE ENSLAVED POPULATION

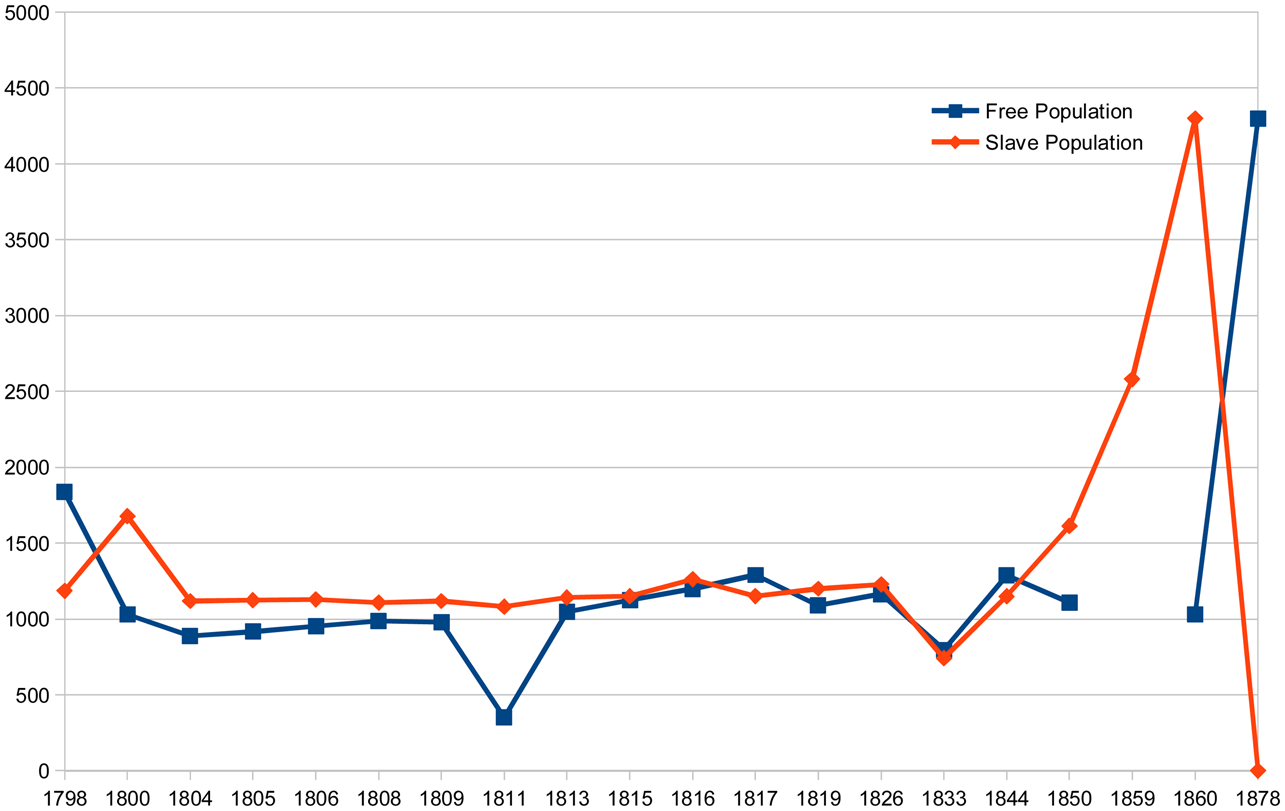

Slavery was central to the economy of Benguela. Residents took part in the slave trade and profited from the auxiliary businesses. Enslaved labor was also vital to the organization of colonial urban space, and unfree people had represented a high proportion of the population of Benguela since its foundation in 1617.Footnote 34 The collection of mapas populacionais, or population counts, since the end of the eighteenth century has made it possible to analyze the size of the free and unfree populations of Benguela. In 1798, for example, there were 1,185 enslaved people in Benguela out of a total population of 3,023 people (see Figure 2). In 1804, the first population account available for the nineteenth century indicates a decline in the overall population, with 889 free people and 1,118 enslaved people identified as living in Benguela. The higher proportion of enslaved individuals than free people continued until the end of the decade. In 1811, the population count identified a surprisingly small free population of 351 individuals, compared to 1,081 enslaved people in the urban center. The population estimates do not include captives in transit, only those who resided in Benguela. These figures lead to questions about the violence and security necessary to control uprisings and flights.Footnote 35

Figure 2. Benguela population by status, 1798–1833.

By 1813, the ratio of free and unfree people was more balanced, as can be seen in Figure 2. By then, the free population was calculated at 1,010 people, while the unfree was 1,141 – a ratio of almost 1:1 that continued until 1826. In the last population counts available prior to the 1836 slave export ban, 796 free and 741 enslaved people lived in Benguela.

Both free and enslaved populations declined in the 1833 population estimate, probably as a result of rearrangements in the slave trade, including the British ban on slave exports in 1808, the ban north of the equator in 1814, and the first attempt to bring slave imports to an end in Brazil in 1826.Footnote 36 Despite these efforts, people continued to be captured, enslaved, and exported from West Central Africa, and Benguela was no exception. However, the shifts in Atlantic commerce did affect the organization of the population of Benguela.

As can be seen in Figure 2, there was an increase in the number of enslaved people in Benguela after the 1836 ban. In 1844, 1,288 and 1,150 free and enslaved people lived in Benguela respectively. While there was a decline in the number of free people (1,106), mainly fewer men, the unfree population jumped to 1,614 people in 1850, representing a ratio of 1:1.5. The size of the slave population in 1859 is derived from the slave register rather than a specific population count, and thus the size of the free population is not certain, but it is important to remember that the end of slave imports in Brazil in 1850 provoked a major population reconfiguration in Luanda.Footnote 37 A similar process seems to have occurred in Benguela, as suggested by the 1860 population count that shows 1,029 free people and 4,298 enslaved people in the town. With the abolition of slavery in Portuguese possessions in 1869, information about enslaved people was no longer collected in the population count. After 1869, the category “slave” disappeared from the estimates, giving the illusion that all people who lived in territories under Portuguese control were free. This masks the fact that slavery remained alive under the name of contrato in the Portuguese empire well into the twentieth century.Footnote 38 By 1878, the Benguela population count listed only free people, numbering 4,298, creating the illusion that everyone enjoyed the same degree of freedom.

THE INSTITUTION OF SLAVERY IN BENGUELA

Since the 1960s, scholars have often discussed the nature of slavery in Africa, with some emphasizing how the institution differed from what developed in the Americas and elsewhere, in terms of skin-color classification, social stigma, and social insertion of slave descendants.Footnote 39 Recent scholarship has emphasized the ways in which slavery continues to shape political and economic access to modern societies, and that slavery in Africa was much closer to slavery in the Americas than scholars were willing to recognize in the 1970s.Footnote 40 There is no doubt that the form of slavery that developed in Angola was shaped by local societies, but also by the fact that the territories were part of the Portuguese empire. In some respects, particularly notions of skin-color classification and emancipation, slavery in Angola had more in common with experiences in Brazil than elsewhere on the continent. During the nineteenth century, the apprenticeship regimes, notions of social mobility, and status and racial classification corresponded to what was happening in Brazil and in the Caribbean during the same period.Footnote 41 This also shows how ideas circulated in the Atlantic world, influencing how colonial officials perceived and operated within legal slave systems.Footnote 42

Enslaved labor was essential to running the colonial center of Benguela. In 1800, for example, the Brazilian-born governor Félix Xavier Pinheiro de Lacerda owned four enslaved children employed as domestic servants. Also serving in his house were an enslaved man called Eusébio and a freed black man, José, who worked as a cook, showing that free and enslaved people worked side by side.Footnote 43 In 1811, the governor of Benguela, António Rebello de Andrade Vasconcelos e Souza, had at least two young girls working as domestic slaves.Footnote 44 In Benguela and in the interior, colonial authorities and residents employed enslaved people, both male and female, in house gardens, especially in the cultivation of maize, beans, manioc, and pumpkin to provide the town's food supply.Footnote 45 Besides these domestic uses within household compounds, enslaved people were also employed as soldiers under Portuguese and African law. In the case of the Portuguese forces, officials employed enslaved males to march in front of the battalion; the military considered them dispensable soldiers. Despite their status as unfree persons, they carried weapons and were used to protect the free population who lived within the colonial centers as well as the long-distance trade caravans traveling inland.Footnote 46

Before and after the 1836 slave export ban, enslaved people worked in mines in West Central Africa. In the interior of Angola, the Cambambe mines required a large number of workers, some of them with skilled training as blacksmiths.Footnote 47 In Benguela, the most important mines were those that extracted sulfur as well as salt. These relied on laborers provided by local authorities, the sobas, who were forced to provide free and coercive labor to the colonial state as a tribute. While sulfur was mined for export, salt was shipped inland and utilized as currency to acquire products such as ivory or wax.Footnote 48 Salt produced in the Benguela region was also exported to Luanda, where it supplied local needs in addition to vessels departing for the Americas.Footnote 49

In a town where no animal transport existed, the colonial state employed enslaved people to convey all kinds of products and people.Footnote 50 Groups of three or four enslaved men carried people in palanquins, unloaded the cargo from anchored ships, and carried both loads and passengers to the decks.Footnote 51 The movement of a passenger to or from a boat required the labor of four slaves to prevent the passenger from getting his or her clothes wet.Footnote 52 Porters provided transportation inside the town and carried all sort of products, including toilet waste.Footnote 53 Porters also carried the luggage of Portuguese administrators and ecclesiastical leaders who were moving to the interior.Footnote 54 Enslaved men and women served as porters for the transportation of weapons, gunpowder, food, and military supplies for expeditions.Footnote 55 In some cases, captives belonged to the administration, but Benguela residents were compelled to provide their own enslaved men, women, and children for colonial expeditions.Footnote 56 These requisitions were not always popular. Masters wanted to avoid losing their labor and tried to get out of sending their captives, even by lying about their state of fitness.Footnote 57

The enslaved population also did most of the work in town as bakers, fishers, and tailors. Enslaved men and women employed in skilled positions enjoyed social status and some level of monetary compensation, which allowed them to save toward manumission.Footnote 58 At the turn of the nineteenth century, António Pascoal was an enslaved blacksmith who belonged to Inés, a black woman. In 1796, Pascoal acquired the support of Benguela's governor to establish a workshop in Benguela with his apprentice, António Felipe, thus becoming the only blacksmith in town.Footnote 59 Fifteen years later, in 1811, Francisco, Dona Maria Domingos de Barros's slave, worked in the royal iron workshop and received a small sum of money for his work.Footnote 60

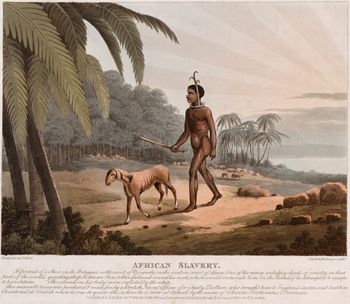

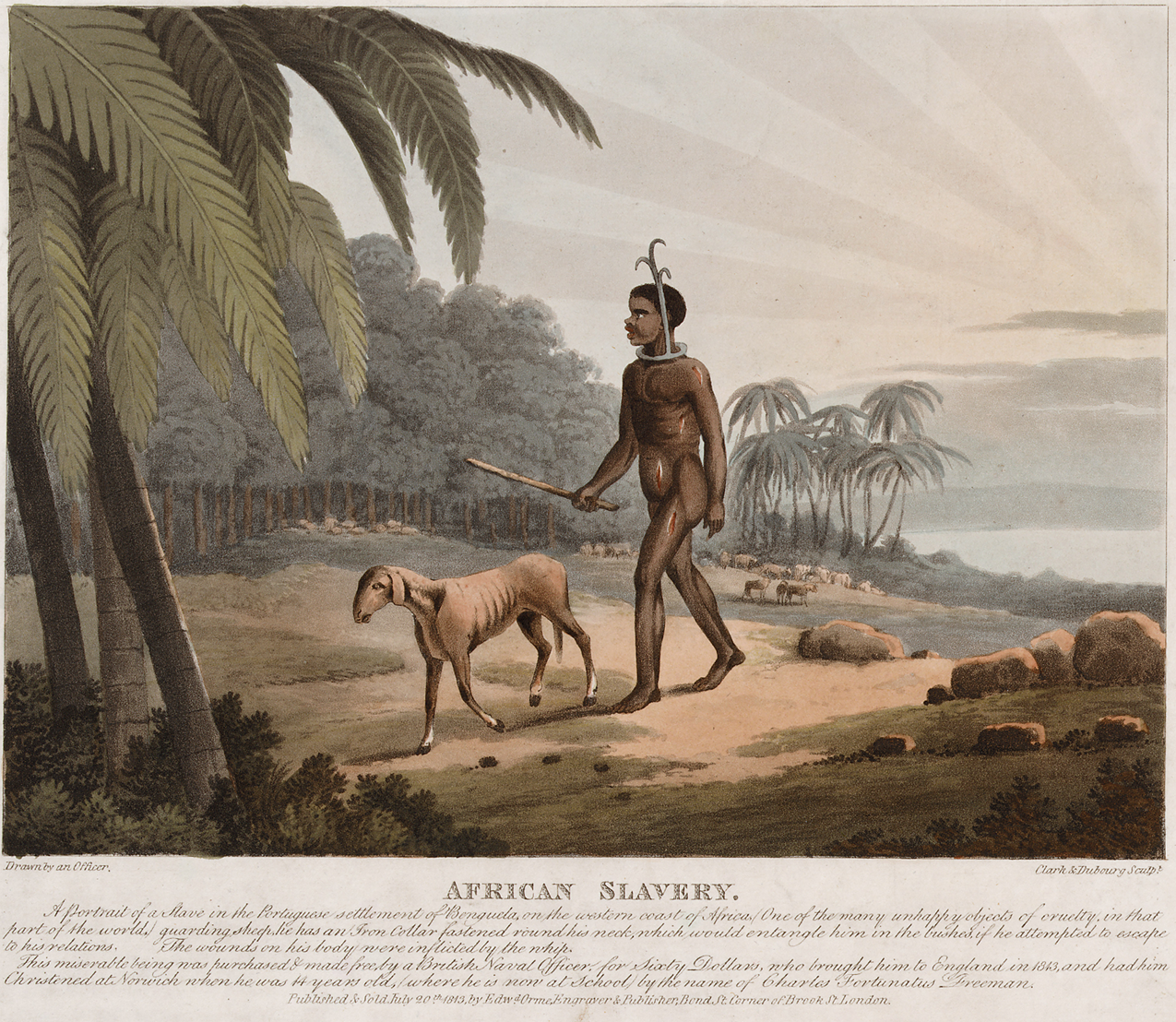

Although enslaved people were everywhere in Benguela, the official correspondence provides little detail about the nature of their lives, their housing conditions, their family and religious experiences, or their daily lives (Figure 3).

Figure 3. “A Portrait of a Slave in the Portuguese settlement of Benguela, on the western coast of Africa. (One of the many unhappy objects of cruelty, in that part of the world) guarding sheep, he has an Iron Collar fastened round his neck, which would entangle him in the bushes, if he attempted to escape to his relations. The wounds on his body were inflicted by the whip. This miserable being was purchased & made free, by a British Naval Officer, for Sixty Dollars, who brought him to England in 1813, and had him Christened at Norwich when he was 14 years old, where he is now at School by the name of Charles Fortunatus Freeman.” Published by Edward Orme, Bond Street, London, July 20th 1813.

SLAVERY AFTER THE END OF SLAVE EXPORTS

According to a report by the traveler Carlos José Caldeira, who visited Benguela in the late 1840s, the houses along the Morena beach served as gathering points for the ivory, wax, gum copal, leather, and orchil exported from the port. Caldeira reported that more than 1,000 enslaved individuals were employed in the cultivation of orchil lichen at different plantations stretching from Benguela to the port of Mossamedes further south.Footnote 61 The use of enslaved labor in major public construction projects such as the building of administrative houses or streets also continued after the slave export ban. To compensate for the physically demanding tasks and to avoid the possibility of escapes that would delay the progress of work, Portuguese agents offered compensation in the form of tobacco or alcohol to the enslaved men and women employed in urban infrastructure construction.Footnote 62

In the 1840s and 1850s, Benguela was a town in transition, moving away from slave exports and toward the use of enslaved labor locally, although smuggling continued to occur. Colonial authorities denounced attempts to embark captives illegally, in part because the continuing export of human beings threatened the expansion of local agricultural enterprise.Footnote 63 In 1854, for example, 194 captives were located in Equimina, a beach south of Benguela, where slave traders planned to export them clandestinely. Among them were fifty-three men, thirty-three women, thirty-seven young girls, sixty-nine young boys, and five babies. The large number of children caught in this single operation underlines the large number of young people deported from West Central Africa in the nineteenth century.Footnote 64 On the farms in Equimina, enslaved people, while secured with chains, iron collars, and shackles, produced, among other items, sugar and aguardente, a distilled sugarcane alcohol.Footnote 65

In the 1860s, the traveler John Monteiro described “the houses [of Benguela] having large walled gardens and enclosures for slaves”.Footnote 66 The visitors reported encountering enslaved people in the streets, in part due to the increase in the enslaved population in the wake of the 1836 slave export ban, the 1850 closure of the Brazilian market, and the local consolidation of the plantation economy, such as the establishment of large farms dedicated to the cultivation of sugarcane.Footnote 67 The 1859 slave register provides some clues about the type of labor performed by unfree people. Male captives were listed with skilled positions including masons, fishermen, carpenters, cooks, and tailors. They also served as barbers, shoemakers, bakers, and sailors.Footnote 68 There are few references to the occupations of enslaved women in the colonial documents, yet the slave register reveals that women also performed skilled labor as seamstresses, cooks, launderers, and street vendors.Footnote 69 All of these urban activities benefited their masters, who profited from their street work. One of the main activities enslaved women performed in Benguela was to supply food and water to a population in constant movement. The concentration of many enslaved street vendors belonging to the same owner indicates that specific residents dominated some urban trade activities. António da Costa Covelo, a Benguela resident, owned thirty enslaved individuals, two-thirds of whom were women. While Covelo employed his male captives mainly in fishing and copper activities, eighteen out of his twenty enslaved women were street vendors. Covelo had only two female captives who were not quitandeiras: Sebastiana, an eight-year-old girl, and Joaquina, a one-year-old toddler.Footnote 70

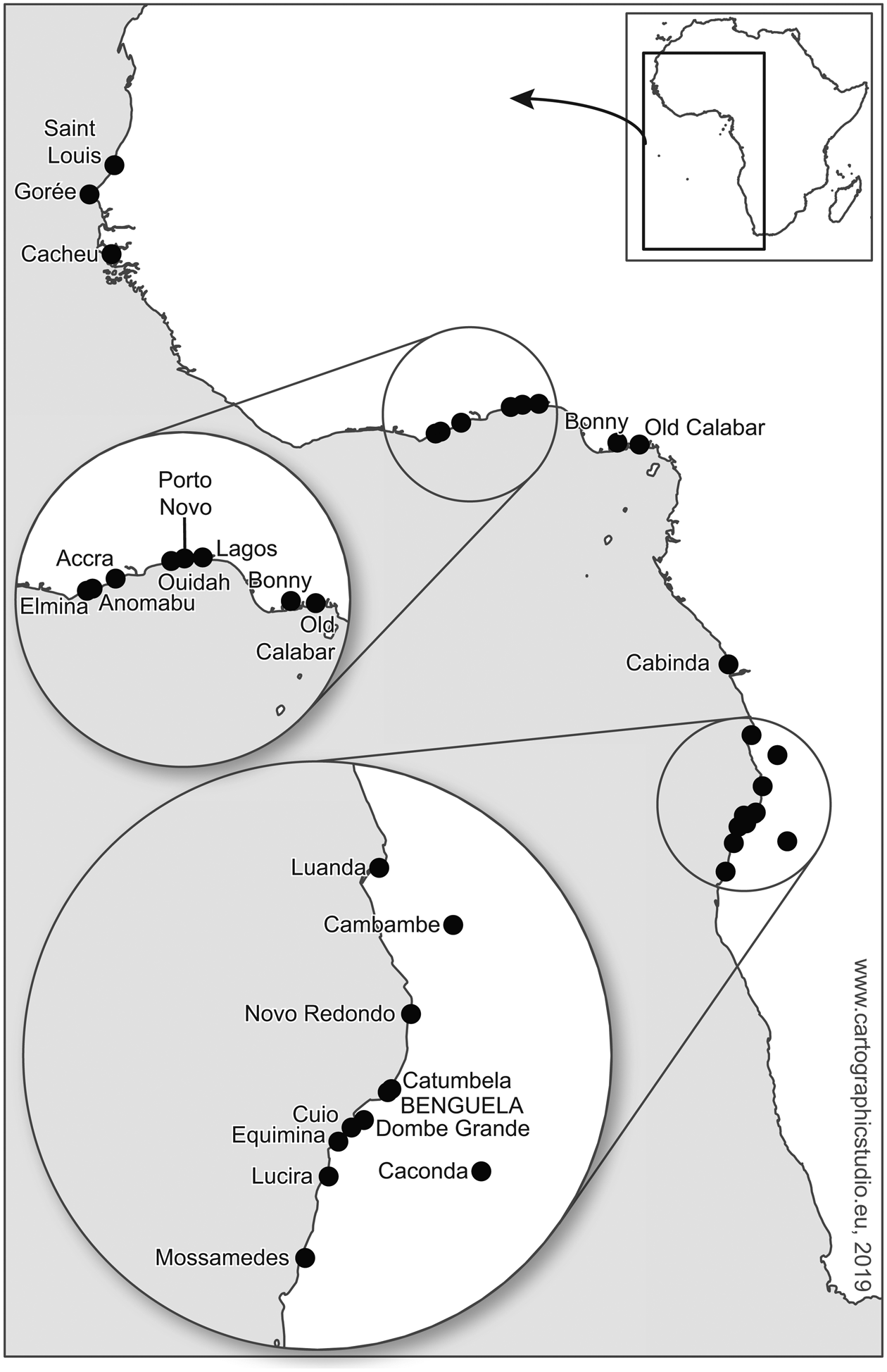

At different times in the nineteenth century, women formed most of the enslaved population in Benguela, as can be seen in Figure 4. As in the pre-1836 period, enslaved women worked on domestic tasks or in the house gardens, but also took part in urban commercial activities.Footnote 71 When employed in domestic tasks, enslaved women cleaned, took care of the house, and cooked; they also acted as nurses, performed many tasks in the house for the slave masters, and met their sexual demands.Footnote 72

Figure 4. Benguela enslaved population by gender, 1800–1880.

With the decline of slave exports and the expansion of legitimate commerce in ivory, beeswax, and then wild rubber, enslaved people were also put to work on the new farms and plantations established around Benguela and in Dombe Grande. There, they provided much of the labor needed for the cultivation of cotton and sugarcane, and for orchil lichen collection.Footnote 73 The businesswoman Teresa de Jesus Barruncho established plantations in Benguela, Cuio, and Dombe Grande. By 1861, she had three different plantations in Dombe Grande; on one of her plantations she had more than 300 captives, many of them women. As a result, Barruncho became the leading exporter of cotton and wax from the port of Benguela.Footnote 74

Reports indicate that, during the 1860s, the landscape was transformed by the expansion of agriculture and the plantation economy as “the great plains that used to be covered by dense woods and served as refuge for wild animals, are now clear of trees, and almost all of the land along the coast is now plantations of cotton and sugarcane”.Footnote 75 By the second half of the nineteenth century, slavery in Benguela resembled the plantation economy in the Americas. While urban slavery continued to be important, many of Benguela's wealthy residents expanded their business activities in surrounding areas by investing in the agricultural economy to export its crops to growing industrialized countries in Europe and North America.

RESISTANCE

Slavery was not mild in West Central Africa, and evidence suggests its violent nature. Severe physical punishment or the threat of being sent to the Americas may have prevented some slave resistance and uprisings, yet they did occur.Footnote 76 The same violence that generated slaves and maintained control over them could also trigger resistance.Footnote 77 The historical registers did not record acts of daily resistance such as working at a slow pace, sabotaging tasks, or breaking tools; the authorities only recorded instances of violent resistance that demonstrated a physical clash with the system.

Events taking place in the Atlantic world and in the interior of Benguela shaped the ways captives viewed their slavery, inclining them to resist, negotiate, or integrate into the host society. Continuous warfare or political turbulence in the interior as well as social insecurity may have led enslaved individuals to negotiate their labor conditions. Moments of change in the Atlantic world or instability after the death of slave masters encouraged many to run away, as scholars have pointed out.Footnote 78 The authorities feared assembled groups of enslaved individuals, perceived as especially dangerous to social stability particularly in a port town with a large enslaved population. When groups of captives confronted each other in the streets, slaveholders and military personnel feared the consequences. In 1814, a group of enslaved men who belonged to Justiniano José dos Regos, a Benguela trader, physically attacked the captives of two other merchants, António Lopes Araújo and Francisco Ferreira Gomes. Colonial soldiers had to intervene to control the street fight and were wounded.Footnote 79 These street fights posed a serious threat to Benguela's colonial administration. In the mid-eighteenth century, any enslaved person caught using a knife against a free person could be punished with 105 lashes plus two months of forced labor at the disposal of the colonial state. On the second infraction the enslaved person faced double punishment, and after the third time he or she could be deported to Brazil. However, by the early nineteenth century, the authorities had changed this last punishment since it would affect the slave owner, who could lose his property overnight. Authorities instead imposed a new penalty: fifty lashes in a public space.Footnote 80

Running away was an effective way to resist slavery. Colonial records suggest enslaved individuals often escaped and moved inland by following the paths of long-distance trade routes, which may have led them back to their homeland or to inland markets to look for help or follow a trail. In 1808, a team led by António headed toward the slave market in Caconda, more than 250 kilometers inland of Benguela, in search of captives who had fled their slaveowners in Benguela. Rumors spread in Benguela that some of António's enslaved females had urged other urban slaves to run away. Feeling responsible, António led a team of armed guards, but it is not clear if they ever located the runaway group.Footnote 81

Free people offering help to runaway slaves could be arrested, as happened with dona Ana José Aranha, a black female trader who moved goods and people between inland markets and Benguela in the first decades of the nineteenth century. A resident in the market of Caconda, dona Aranha was one of the largest slave owners and food producers in the inland fortress. In her compound dona Aranha controlled 266 people, including eighty-four enslaved people who cultivated beans and manioc in her fields. Part of her production was probably destined to supply the Benguela population's demand for food. On one of her journeys to Benguela, another trader reported seeing some Benguela runaway captives employed in dona Aranha's caravan. The governor of Benguela ordered her arrest, alleging she was offering protection to runaway slaves and colonial soldiers who had abandoned their positions.Footnote 82 Four decades later, offering asylum to runaway slaves was punished not with arrest but with a fine. In 1846, Rita, a free black woman and resident of Benguela, received a fine of 100,000 reis for hiding two runaway captives. Two runaway women found refuge in Rita's compound after escaping their master's establishment in Benguela. Rita lived close by, and it is not clear if she participated in the escape. Since she had offered asylum and was caught, she was required to pay the fine imposed by the governor.Footnote 83

Although some people were successful in fleeing captivity, the fear of being recaptured was real. This may explain why some individuals would return to Benguela and buy their manumission even after years spent living as a free person. This was the case with José Eleutério, who belonged to the Santa Casa da Misericórdia, the Holy House of Mercy, a Catholic lay institution intimately linked with Portuguese colonialism that operated a hospital in Benguela. When José Eleutério ran away the administrator of the hospital agreed to free him in exchange for 300,000 reis. Over three years later, Eleutério returned to Benguela, paid his manumission, and received his freedom letter in August 1817.Footnote 84 Cases in the Tribunal da Comarca de Benguela, the courthouse of Benguela, reveal that slave masters resisted freeing their captives even if they managed to save the money to buy their freedom.Footnote 85 Unlike Eleutério, Dorotéia, a runaway enslaved woman, was not able to buy her manumission after escaping her master. She served in the house of Lieutenant José Rodriguez Guimarães for many years until 1837, when she finally found an opportunity to flee. It appears she was able to escape north to the port of Novo Redondo, where she lived as a free trader. However, nine years later in 1846 a colonial officer identified her and informed Guimarães of her location.Footnote 86 It is unclear whether Dorotéia was recaptured. This case clearly reveals that colonial officers kept track of runaway individuals and searched for them even years after their flight.

The fear of runaway captives was constant in Benguela, in part because African rulers could easily offer refuge. The records suggest that running away was a successful strategy for most of the nineteenth century.Footnote 87 Only on very few occasions were colonial forces successful in locating and recapturing runaway individuals.Footnote 88 Under African rulers’ jurisdiction, unfree people found mechanisms to escape, even committing crimes to be re-enslaved by someone else who became their new master. Cases like these, known as tumbikar, are rare in the Portuguese documentation since such events occurred beyond the Portuguese scope, but some itinerant merchants reported encountering cases of enslaved people willing to change masters. These cases are only attested for the period after the 1850s when these accounts were recorded.Footnote 89

The existence of maroon communities in areas surrounding Benguela demonstrates that successful escapes were more common than the colonial sources indicate.Footnote 90 Anyone who offered asylum to runaway slaves could face severe retaliation. In the 1840s and 1850s, authorities and slave owners sometimes accused free or freed blacks of helping runaway slaves with promises of better and safer lives. The Benguela trader António Joaquim Monteiro accused Matias, also known as Matias do sertão, of convincing Monteiro's captives to run away in 1848. Sixteen of Monteiro's enslaved individuals planned to escape to the interior, but only three succeeded. With the collaboration of colonial forces, Monteiro later apprehended all of them, including one in Matias's company. All of them quickly blamed Matias for their actions.Footnote 91 Free black people helped runaway slaves, usually leading them toward the interior in search of the protection of African rulers. Zambo, a free black man from the Dombe region, helped an enslaved woman belonging to dona Margarida to escape. In 1847, Portuguese agents pursued and captured both in the interior.Footnote 92 Occasionally, African rulers returned the runaway individuals to the Portuguese authorities, as in the case of the soba Marango from Ganda who recaptured a portion of the 130 runaway captives who had escaped from Marques Esteves, a resident of Catumbela. For his cooperation, the soba received ten firearms, gunpowder, textiles, and alcohol. However, soba Marango also wanted a cash reward beyond the goods he received.Footnote 93 One can only imagine the punishment that recaptured runaway enslaved individuals endured, since the historical documents provide little information.

Running away was relatively easy and offered a greater chance of success than more aggressive alternatives such as violent attacks against slave owners or uprisings. It also offered quicker access to freedom than negotiating access to manumission. The colonial records are limited and problematic and provide few clues about daily resistance. For example, unlike the case of Luanda, no information has been located on runaway slave announcements.Footnote 94 The number of escaped captives who were never recaptured is unknown. The sources are also limited to enslaved individuals under Portuguese jurisdiction, so little information is available on the nature of resistance of enslaved individuals who lived under the jurisdiction of African rulers.

CONCLUSION

The nineteenth century can only be considered the age of emancipation if we ignore the fact that the slave trade expanded after 1801 in the South Atlantic world. Unlike other places in the Atlantic world, in Benguela the nineteenth century was not a moment of freedom but a period when slavery expanded dramatically. Although slave exports were prohibited in 1836, the trade in human beings continued until the 1860s. In fact, the use of slave labor expanded after 1836 and the number of enslaved people in Benguela increased. In the colonial center enslaved people performed most of the work, both public and private. In the wake of the end of the slave trade, so-called legitimate trade expanded. Ironically, the legitimate commerce relied on forced labor to supply the growing demand in Europe and North America for cotton, sugar, and natural resources such as wax, ivory, rubber, and gum copal. Thus, any attempt to portray the nineteenth century as an age of freedom and liberty excludes not only West Central Africa, but also events in other parts of the Atlantic world such as Brazil or Cuba.

In Portuguese territories in West Central Africa, slavery remained alive until 1869, when enslaved people were put into systems of apprenticeship very similar to labor regimes elsewhere in the Atlantic world. For the thousands of people who remained in captivity in Benguela, the nineteenth century continued to be a time of oppression, forced labor, and extreme violence. Yet, enslaved individuals resisted through flight and small acts of resistance that sabotaged masters and the colonial economy. Their resistance indicates that slavery in West Central Africa was as violent and oppressive as anywhere else in the Atlantic world.