Introduction

The debate on authoritarian diffusion is relatively new and reflects mounting fears for the crisis of liberalism and ‘the end of the end of history’ (Kagan, Reference Kagan2009; Schmitter, Reference Schmitter2015; Diamond et al., Reference Diamond, Plattner and Walker2016; Cassani and Tomini, Reference Cassani and Tomini2019). While the actual success of authoritarian diffusion initiatives is a matter of debate (Tansey, Reference Tansey2016; Way, Reference Way2016; Chou, Reference Chou2017), its study has opened up interesting and much needed conversations about the transnational dimension of authoritarianism, including studies that centre the international complicities that guarantee its survival (Ambrosio, Reference Ambrosio2014; Mullin and Patel, Reference Mullin and Patel2015; Gervasio and Teti, Reference Gervasio, Teti, Corrao and Redaelli2021; Topak et al., Reference Topak, Mekouar and Cavatorta2022) and comparative studies that question the practical and theoretical distinction between democracy and authoritarianism in an era of ‘democratic pessimism’ (Tagma et al., Reference Tagma, Kalaycioglu and Akcali2013; Teti and Mura, Reference Teti and Mura2013; Wood, Reference Wood2017). This article builds on this scholarship, but also expands it by focusing on another – less investigated – dimension of how political authoritarianism travels internationally: its discursive and narrative form. In fact, while scholars have broken down authoritarianism in practices, policies, and enclaves (Benton, Reference Benton2012; Glasius, Reference Glasius2018), less is known about authoritarian discourse and narratives, how they travel across borders, and how local actors in other countries appropriate them.

This article contributes to fill this gap and, by doing so, shifts the perspective from the state articulating and promoting the authoritarian discourse, to the actors that are on the receiving end of it as well as to those actors who facilitate this transmission. The article does not only offer an analysis of the discourse emanating from the authoritarian state but crucially, it examines how it is transmitted, received and translated by and for the local community. As little is known about the reception of authoritarian discourses and narratives by targeted audiences (Kneuer and Demmelhuber, Reference Kneuer and Demmelhuber2020; Gurol, Reference Gurol2023), this contribution does not only provide fresh findings about a lesser-studied dimension of authoritarian diffusion, but also engages the question of whether targeted audiences respond to authoritarian narratives for ideological or interest-based reasons (Bank and Weyland, Reference Bank and Weyland2020).

The case of Italy's far-right organizations responding to Iran's authoritarian discourse is examined. Iran as an ‘authoritarian narrator’ (Gurol, Reference Gurol2023) is less analysed than bigger and more powerful countries such as China and Russia. Furthermore, Iran's international activities are rarely examined outside the Middle East and geographies that have a cultural affinity with it. The choice of this case study is also motivated by other factors, which shift the attention to the receiving end of Iran's influence. The first factor is the surge of visibility of the far right in Italy, which predates but is also part of the transnational success of right-wing, authoritarian populism and ‘sovranism’. The second factor is the decade-long interest of Italy's far right in Iranian politics, nationalism and political Shiism, which dates back to pre-1979 times. It has built on the historical connections drawn by conservative political Traditionalism in the past century (Laruelle, Reference Laruelle2015b; Sedgwick, Reference Sedgwick2019) and has been more consistent than the interest manifested by the left. Finally, this case study contributes to shed light on the construction of transnational relations between illiberal actors in the era of right-wing populism, to understand and explain the far right as ‘an internationally interconnected yet ideo-politically variegated global phenomenon’ (Anievas and Saull Reference Anievas and Saull2022: 1; Gurol et al., Reference Gurol, Jenss, Rodríguez, Schuetze and Wetterich2023). In fact, while studies exist on this issue (Laruelle, Reference Laruelle2015a; Shekhovtsov, Reference Shekhovtsov2017; Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2018), they hardly move the focus away from the ‘usual suspects’ – Russia and China.

Literature review and background

This article examines the diffusion of authoritarian discourse and its cross-border reception; and Iran's soft power and the modalities through which this country fashions its international engagement, targeting specific audiences according to contextual interests as well as historical linkages. This section also discusses the historical background to the current relations between the Iranian state and Italy's far-right galaxy, offering a grounded perspective on the transnational connections between Traditionalist and illiberal actors that goes beyond the contemporary ‘populist moment’ in international politics.

Authoritarian diffusion and its reception

Narratives and discourses are a fecund field for interrogating authoritarian diffusion. A narrative is a form of context and time-specific communication, often aimed at presenting events in a particular way, while a discourse is a general pattern of communication that is not bounded to a specific context, time, place, or event. It aims at providing a general framework to read large political and historical processes (Patterson and Renwick Monroe, Reference Patterson and Renwick Monroe1998; Bliesemann de Guevara, Reference Bliesemann de Guevara2016). In her work, Gurol (Reference Gurol2023) has examined how the diffusion of Chinese narratives of success in managing the Covid-19 pandemic has had an effect in the Gulf, strengthening the idea that in international politics there are more than one hegemon to look up to for governance models. Examining al-Sisi regime's positive response to Chinese propaganda, Rasheed (Reference Rasheed2022) has theorized the concept of authoritarian reinforcement, by which local actors utilize authoritarian discourses coming from abroad to reinforce the legitimacy of their actions and ideas locally.

The study of state propaganda from the perspective of the state producing and diffusing it, has prominently featured in the study of political authoritarianism (Kurlantzick, Reference Kurlantzick2007; Von Soest, Reference Von Soest2015; Kneuer and Demmelhuber, Reference Kneuer and Demmelhuber2020). Countries such as Russia and China are active with a variety of objectives across borders. By discursively presenting themselves with distinct values and characteristics such as non-interference, sovereignty and policy efficacy, the aims of authoritarian diffusion may range from influencing foreign media systems and creating sympathetic audiences, to expanding opportunities for economic growth and investments (Nathan, Reference Nathan2015; Dukalskis, Reference Dukalskis2021). Regardless of its objective, state propaganda attracts sensitive audiences at the local level reinforcing thus the legitimacy of the authoritarian state, what it does and says. In fact, authoritarian discourse and narratives produce ‘significant imaginaries’ that are ‘a useful resource for authoritarian leaders, both to bind their audiences to their rule and to create a certain connection by appealing to people's emotions as well as by strategically projecting certain images’, creating transnational ‘linkages via attraction, persuasion or admiration’ (Yellinek, Reference Yellinek2022; Greene and Robertson, Reference Greene and Robertson2022; Gurol, Reference Gurol2023: 5). Therefore, narratives and discourses are powerful political instruments that authoritarian leaders can use to increase their appeal abroad.

Shifting the attention away from the states producing and diffusing the authoritarian discourse, less is comparatively known about the receiving ends of it and about the actors translating it for the local audiences that are targeted. The investigation of the human and material resources that enable diffusion is in fact less consolidated in the scholarship, and the debate on authoritarian diffusion has narrowly and traditionally foregrounded the motivation of the authoritarian state diffusing authoritarian policies and discourse; or, the measurement of the success of such initiatives. The ‘chain of transmission’ has been less researched, although it remains of crucial importance to diffusion mechanisms. While filling this gap, this paper also makes an intervention in the scholarly debate about whether actors on the receiving end respond to the authoritarian discourse because of interest-based calculations or ideological affinity. Following Bank (Reference Bank2017: 1346), this article argues that, contextually, ‘interest trumps ideology’, emphasizing the ‘egoistic’ contextual interest that target audiences may have in the authoritarian discourse in order to advance their own objectives and/or strengthen their own narratives. However, at the same time, ideological affinities reinforce such an interest, making it resilient in time. In the case considered, this two-fold argument is particularly fitting. In fact, the far right in Italy has today an interest in Iran's nationalist, anti-liberal, anti-‘gender ideology’ and sovereignty-centred authoritarian discourse because it reinforces its own specular discourse. However, this discursive overlap is not purely contextual or limited to the current ‘populist moment’. In fact, as mentioned earlier and discussed later in this article, an historical connection exists between the two. It is thanks to such a longer history of exchanges and shared ideals that Italy's far-right networks respond positively to the Iranian state's authoritarian discourse, stressing their ideological affinity and using it according to contextual interests.

Iran's diffusion initiatives and their reception in Italy

Despite being less powerful than Russia and China, the Islamic Republic too engages in discursive authoritarian promotion. Iran often reproduces discursive patterns similar to those of the two more powerful states, promoting the values of self-determination, sovereignty, non-interference, and highlighting the hypocrisy of what is called ‘the West’,Footnote 1 especially when it comes to its double standards in respecting human rights. However, Iran also emphasizes its own cultural specificity that sets it apart from Russia and China, by referring to the role of religion in the public sphere and the higher moral status of its domestic and foreign politics given that both derive from Islam, so the Iranian state argues. Iran's soft power and immaterial resources for promotion are often understudied to the benefit of more ‘sensational’ aspects, such as its military activism in conflict areas. Furthermore, Iran is often portrayed as an ‘ideological state’ unable of rational choices and policies, hence its muscular approach to international and regional politics (Ansari, Reference Ansari and Katouzian2007). It follows that scholars have comparatively dedicated little attention to ideas and discourses outside of this framework.

There are, however, exceptions and studies focusing on Iran's soft power and international promotion. These have highlighted that, indeed, Iran's international effort is multifaceted and enacted through different modalities (Von Maltzahn, Reference Von Maltzahn2013; Warnaar, Reference Warnaar2013; Wastnidge, Reference Wastnidge2015). One of the most important promotional activities of the post-1979 Iranian state is the marketing of its identity. Scholars have examined how such identity is articulated, at times, emphasizing that of a great civilization contributing to the history of humanity, at other times focusing on the religious aspect of it or, on other occasions, stressing Iran's ‘resistant’ political identity as a country fighting imperialism (Holliday, Reference Holliday2016). Not only authoritarian discursive strategies vary according to the content being branded, but also to the target. Assessments on the palatability of the content are in fact never disjointed from assessments of the targeted audience, whether more general or specific. Currently, considering its unpopularity since the repression of the Woman Life Freedom uprising, Iran limits its activism by design, targeting specific audiences with dedicated contents and with the objective of cultivating discrete publics. In the case of the far right, Iran's authoritarian discourse emphasizes topics that are palatable to that audience, centring Iran's nationalism, the fight against liberalism and its willingness to support like-minded anti-imperialist efforts and organizations, regardless of their religion.Footnote 2

The Iranian institutions and state actors involved in promotion and diffusion efforts are different and might have different agendas. It would be inaccurate, in fact, to portray the Iranian state as uniform. In particular, two offices are involved in the field of public diplomacy, notably the Supreme Leader's and the presidency of the Republic. Wastnidge (Reference Wastnidge2015: 366) elaborates on the impact of this dual system on how Iranian soft power is projected and managed abroad. He explains that the ‘President performs one role in terms of representing Iran on the world stage, while the Supreme Leader maintains control over some important soft power tools, such as […] international media operations and cultural attaches and related cultural outreach centres’. Because of this duality, when the President and the Supreme Leader have different ideas about what image Iran should present abroad, such differences may become evident in the form of a conflict of narratives. This happened in the past (Wastnidge, Reference Wastnidge2016) and the reverberation of such internal factional conflicts reached the Italian converts community too, with conservative converts, connected to the far right and loyal to the Supreme Leader Khamenei, entertaining public polemics and controversy with the more liberal-minded Iranian diplomatic institutions in Italy, controlled by the President of the Republic (Mirshahvalad, Reference Mirshahvalad2020). This is not a casual pattern of conflict. Governments and presidents are elected and change, and so do their more or less liberal attitudes and foreign policy. The agenda and the public discourse of the state institutions controlled by Supreme Leader, on the contrary, are generally more impactful and discursively more stable because the Supreme Leader is an office one holds for life.

This study pays attention to a set of institutions and state actors that are under the control of the Supreme Leader and that present a more conservative, anti-Western and illiberal political discourse. However, shifting the analytical focus to the receiving end, this paper examines the role of those political and cultural entrepreneurs who pick up the state's authoritarian discourse, mediate and popularize it within specific networks in Italy, and who inhabit a liminal space between political conservative networks of Italy and Iran. Such cultural and political entrepreneurs, who can be called ‘the mediators’ for their work of translating the official discourse for the local audience, include Italy-based Iranian individuals and Italian-Iranian individuals who work for the Iranian state and/or are loyal to the Iranian Supreme Leader; and Italian organizations (such as research centres, religious associations, publishers) that entertain contacts with both the Iranian state and its ramifications in Italy, and far right organizations. It is argued that such non-state, liminal actors between Iran and Italy play a fundamental role in mediating the Iranian state's discourse, translating and contextualizing it for far-right audiences. It also is important to highlight that many of such mediators share political and ideological persuasions with the far right, as exemplified by the hostility toward the celebrations of the Italian liberation from Nazi-fascism on April 25th. An example of this is an interview to Mostafa Milani Amin,Footnote 3 an Iranian-Italian cleric and collaborator of the Iranian International University al-Mustafa,Footnote 4 originally published in the rightist newspaper Il Giornale and re-published in the far-right Il Primato Nazionale, which eloquently titles ‘An Assad-less Syria would end up like Italy after April 25th: In the hands of terrorists’,Footnote 5 where ‘terrorists’ refers to post-1943 Partisans' armed formations that captured Mussolini and liberated Italy from Nazi-fascism. The following section discusses the historical background to these connections, for their construction is grounded in time and consolidated in history.

Italy's far right and Iran: past and present connections

During the 20th century, non-Western religions and Islamic mysticism (Sufism and irfan, Shi'a mysticism or gnosis) have been a pole of attraction for Traditionalist, far-right and fascist ideologues, because they were seen as uncorrupted by Western modernity (Sedgwick, Reference Sedgwick2009). Such a cultural interest also had a geopolitical aspect, as exemplified by the work of the Italian fascist thinker Julius Evola (1898–1974) and the Italian journal Geopolitica (established in 1939) whose ambition was to elaborate a fascist foreign policy (Savino, Reference Savino and Laruelle2015). According to them, the fascist state was in direct competition with other European colonial powers, Great Britain in primis. Italy had to maintain a ‘good neighbour’ policy towards, and cultural relations with, Russia and the Muslim world, its natural allies in the fight against British imperialism and soul-less industrial modernity.

Evola's work became popular in the 1970s and 1980s. During those years, an interest in and admiration for khomeinism as a force against modernity strengthened the far right's interest in Shi'a mysticism, esotericism and political Traditionalism – and in Evola's work too. Those who gathered around radical right-wing and neofascist magazines such as Orion, Avanguardia, Aurora and Dissenso considered Islam as an ally in the fight against liberal globalization and its brand of modernity. Many converted to Shia Islam, too. Examples include Dagoberto Hussein Bellucci, collaborator of Avanguardia and Eurasia, a journal founded in 2004; Pietro Benvenuto, a former member of the neofascist organization Ordine Nuovo and active in Morabitun-The World Movement of Western Muslims; and Luigi Ammar De Martino (d. 2019), another former Ordine Nuovo member. De Martino established the magazine Il Puro Islam and the association Ahl al-Bait in Naples, which has close relations with the Tehran-based mother organization which is under the control of Iran's Supreme Leader Khamenei (Ra'ees and Kamal, Reference Ra'ees and Kamal2017). From the Naples-based Ahl al-Bait split the religious Imam al-Mahdi cultural centre, with branches and associated organizations in Rome and Milan. The Imam al-Mahdi cultural centre is headed by converts Shaykh Abbas di Palma and Marco Hussein Morelli, a collaborator of the neofascist and Catholic fundamentalist magazine Fuoco.Footnote 6

Central to these networks, both in the past and today, are Claudio Mutti (b. 1946) and Carlo Terracciano (1948–2005). Mutti, who has been involved in far-right cultural initiatives since the 1970s, converted to Islam in the 1980s and established the Italian section of the organization Morabitun. Terracciano was editor of Orion and Avanguardia. Footnote 7 Since the 1990s, both have supported the need to overcome the right vs left political divide to embrace common anti-imperialist and anti-liberal positions. Mutti and Terracciano also played an important role in popularizing Aleksandr Dugin's Eurasian geopolitical vision in Italy. Dugin combined mysticism and Aryanism with geopolitics to theorize the alliance of Slavic and Muslim civilizations to oppose Western liberal imperialism and globalization, an idea that the Italian far right was already familiar with through Evola's work. In 1993, Mutti and Terracciano attended the First World Congress of the Peoples Oppressed by the New World Order in Moscow, where delegations from several countries, including Iran, met to consolidate alliances and a common anti-liberal and sovereignty-centred political discourse (Savino, Reference Savino and Laruelle2015).

With the mainstreaming of Dugin's theories since the 2000s in Italy (Piraino, Reference Piraino, Piraino, Pasi and Asprem2023), the geopolitical aspect of the far right's interest in Iran became prevalent, although interests in Islam and mysticism never disappeared. As Mutti put it during an interview, his generation's early interest in Iran and Islam was motivated by ‘the search […] the want for spiritual fulfilment and an alternative to Western existential materialism’.Footnote 8 However, he continued, today this spiritual approach has to be overcome in favour of a more militant one to initiate a common international struggle against global liberalism and the ‘New World Order’. In this context, the insistence on shared values aims to counter the Islamophobic sentiment prevalent today within the far right,Footnote 9 emphasizing that the struggle is against the common oppressor, liberal globalization.

In a similar vein, Hanieh Tarkian (an Italian-Iranian lecturer at the Rome branch of the al-Mustafa International University, a frequent commentator for far-right Italian publications such as Il Primato Nazionale, among the others, a regular contributor to the magazine Il Puro Islam, and a member of the Eurasiatist Dimore della Sapienza research centre) foregrounds the imperative of solidarity among the oppressed peoples to resist against global liberalism:

‘…’ there is a war today between oppressive elites and oppressed peoples, such as the Italian people. The Italian people live a double oppression. On the one hand, liberal (mondialiste) war-mongering elites create impossible situations such as the migrants crisis. On the other hand, pseudo-sovranist elites do not offer any solutions and present Islam as the enemy, ignoring the fact that Muslims too are oppressed by liberal and war-mongering elites. This situation causes a conflict among the oppressed […] On the top of this, Western governments allied with those Middle Eastern countries that sponsor terrorism, and [allowed them to] establish obscurantist religious centres in Europe. Obscurantism preys upon the identity crisis of […] Muslim migrants in Europe, and upon Westerners’ […] identity crisis. This is why many ISIS terrorists are of European origin’.Footnote 10

The weakening of identity and tradition, the hypocrisy of Western liberal elites, along with hostility against feminism and what they call ‘gender ideology’ (Lavizzari and Prearo, Reference Lavizzari and Prearo2019; Paternotte, Reference Paternotte2023) are the issues upon which the far right's and Iran's discourses overlap today. The following section discusses the methodology adopted to examine such overlaps.

Data and methodology

This article draws on eighteen Iranian and Italian social media accounts in Italian across different platforms (YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Telegram) to analyse the content of Iranian authoritarian discourse and narratives; and the reception of them. Hundreds of posts/tweets and thirty recorded conferences have been examined. With some exceptions, the time span observed goes from the beginning of 2020 – which opened with the killing of IRCG General Ghassem Suleimani in Iraq – to 2023. This temporal arch has been selected for two reasons. First, it provides rich empirical material considering the density of the events that have characterized this period (from Suleimani's death to Covid-19 pandemic and the Woman Life Freedom uprising). Second, this contemporary focus integrates the scholarship that already exists on the topic of the rise of the far right in Italy and Iran's foreign policy.

Through the analysis of selected Iranian social media accounts in Italian, it is possible to identify the state's authoritarian discourses as intentionally aimed at Italian-speaking audiences. The following institutional accounts have been considered: the Supreme Leader,Footnote 11 Iran's International State Broadcast IRIB and its website Pars Today,Footnote 12 the Iranian Embassy in Italy and the Consulate in Milan.Footnote 13 A particular mention should be made of the Italian chapters of the al-Mustafa International University. Not only they organize seminars and educational activities for Italian audiences, but also co-organize conferences with far-right organizations and provides speakers for media and public events.

As this article centres the reception of Iran's authoritarian narratives and discourse by Italy's far-right audiences, the role of the actors mediating between the ‘authoritarian narrator’ and its intended audience is fundamental. Iranian accounts diffusing the official discourse of the state in Italian, in fact, explicitly target audiences in Italy, although it is these actors mediating and translating the content of the original messaging to make it relevant to the local far-right audience. Such mediators are cultural and political entrepreneurs. They are Italian and/or Iranian individuals and organizations that entertain contacts with, on the one hand, institutions officially part of the Iranian state and/or its diplomatic representation in Italy and, on the other hand, with far-right organizations and platforms. The selected ‘mediators’ are the International Research Centre Le Dimore della Sapienza,Footnote 14 the Imam al-Mahdi Cultural Centre,Footnote 15 and publisher Irfan Edizioni.Footnote 16 Along with these organizations, there are Italian, Iranian, and/or Italian-Iranian individuals who play an important role as ‘mediators’. For this study, the social media profiles of the following individuals have been identified as relevant: Hanieh Tarkian,Footnote 17 Giuseppe Aiello (director of Le Dimore della Sapienza and Irfan Edizioni),Footnote 18 and Shaykh Abbas Di Palma.Footnote 19 They mediate and reinforce connections and ideological affinity. On public speaking occasions, they identify areas of shared political interest, showing the far right how the authoritarian narratives and discourse coming from Tehran overlap and reinforce local nationalist, anti-liberal and traditionalist analyses.

As for the far right, the following organizations and platforms have been identified as relevant: Il Primato Nazionale, Idee&Azione, Fuoco, Radio Spada. Il Primato Nazionale Footnote 20 is the flag publication of one of the most important far-right and militant organizations of Italy, Casa Pound. The magazine/cultural hub Idee&Azione Footnote 21 defines itself as ‘the voice for the Organic Communities of Destiny’, a group of twelve far-right organizations among which is Le Dimore della Sapienza.Footnote 22 On Telegram, Idee&Azione self-describes as ‘the official voice of the International Eurasiatist Movement in Italy’. Fuoco and Radio Spada, which are close to Catholic fundamentalist networks, are comparatively less known, but have been active in offering platforms and space to the cultural and political mediators identified above.Footnote 23

The cultural and political entrepreneurs have been identified during the coding process of the authoritarian discourse diffused through Iranian institutional accounts. Their activism and role in disseminating Iran's state propaganda became evident on social media through retweets and shares, hence their role as ‘the mediators’. To reconstruct responsive far-right networks and identify the relevant players, Iranian institutional accounts as well as the mediators' accounts and their participation in events have been used as proxies. It is important to emphasize that neither the mediators nor the receiving far-right organizations are structured in a defined, uniform group. This article does not argue that Italy's far right is a monolithic galaxy sympathetic to Iran, and there is a degree of approximation when it comes to the selection of the relevant far-right actors for this study. In fact, the method followed (retweets, shares, recurrent references, co-organizations and participation in seminars and events, invitations as speakers and commentators) is similar to the snowballing technique for interviews, which presents a bias as it privileges interviewees with an ideological affinity. My selection method has a similar limitation, as it is based on tweets, shares and co-organized events. In spite of this, it is important to emphasize that snowballing is a widely accepted technique for selecting interviewees. Moreover, the size of the material collected and examined, plus the resources that these networks seem to have, considering that they are able to sustain integrated cultural and political activities from conferences to independent publications and media presence, which imply the availability of material as well as human resources, suggest two considerations. First, that these are dense networks, which expand but maintain a high degree of ideological and relational cohesiveness internally; and second, that they are relevant, representative, and can reach a sizeable audience beyond their confines, thanks to the resources they have.

The coding process proceeded quite intuitively through two steps. First, Iran's authoritarian discourses were identified via the relevant social media accounts. The second step consisted in the application of these discourses to the material collected from Italy, to analyse whether and how they overlapped.

Iranian authoritarian discourse and narratives

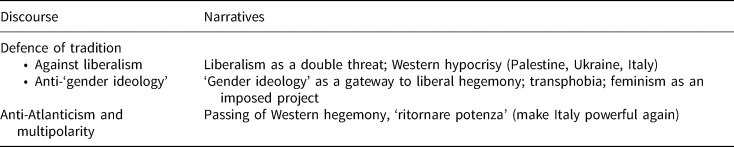

Following this methodology, two discourses were identified. The first discourse is one of superiority and has three dimensions: moral and normative superiority, political and systemic superiority, and performative superiority. Moral and normative superiority is often articulated through narratives of Western hypocrisy in international politics and other areas (such as women's rights), the commemoration of the Iran–Iraq war martyrs, and Islamic teachings. Political and systemic superiority centres narratives related to the revolution and Iran's dependence. Performative superiority is about the successes of Iran despite international sanctions. The second discourse is a sum of the previous narratives and promotes the idea that Western global hegemony is weakening in favour of multipolarity and a more egalitarian international community. The most relevant and salient empirical material, as selected during the coding process, is utilized below to discuss Iran's authoritarian discourses and narratives Table 1.

Table 1. Iran's authoritarian discourses and narratives

Moral and normative superiority

The Islamic Republic self-brands as a morally superior political community through specific narratives that revolve around Western hypocrisy as opposite to Iran's commitment to justice, inspired by religion. The West's double standards in international politicsFootnote 24 is an important discursive trope around which Iran has built many narratives, from the Iran–Iraq war (1980–1988) and the defence of its own nuclear programme,Footnote 25 to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and, more recently, the demand that France respects the human rights of protesters during the mobilizations against the pensions reform.Footnote 26 While circulating these specific narratives to Italian audiences, the mediators selectively ignore another narrative which is important to Khamenei: Western colonialism and its history of institutionalized racism,Footnote 27 which are used by Khamenei to further illustrate the West's hypocrisy and double standards, especially when it comes to its commitment to uphold human rights internationally. ‘Tragedy, sacking, torture’ are defined as the ‘chef d'oeuvres’ of the West.Footnote 28 In another illustration, the Supreme Leader Khamenei denounces the hypocrisy of those countries that supported Saddam Hussein, who committed major human rights violations, during the Iran–Iraq and are today presenting themselves as human rights champions.Footnote 29 Khamenei also used the Western conduct vis-à-vis the Russian invasion of Ukraine as an example to uncover racism and hypocrisy: ‘everyone saw the West's racism in Ukraine. They help white refugees escape on a train, while those of colour are asked to leave that train’,Footnote 30 a narrative which the mediators have purged of its reference to racism in their translation for Italy's far-right audiences. Instead, Western proactive attitude in defence of Ukraine and the contrast with its negligence of the rights of the Palestinians is used by both Khamenei and the mediators in their work of translation for the Italian audiences.Footnote 31

In opposition to such hypocrisy is Iran's morality, which is the result of ‘paying attention to God, the Highest, and to spirituality’, Khahemeni argues.Footnote 32 The martyrs of the Iran–Iraq war are the symbol of it,Footnote 33 as they gave their life ‘not only for the defence of our geographical borders, but for faith, ethics, religion, culture and identity’.Footnote 34 Using the hashtag ‘selfless’, the IRCG General Suleimani is celebrated as an anti-terrorism hero, ‘protector of the oppressed and advocate of the women and children suffering from oppression and foreign invasion’.Footnote 35 Religious faith strengthens Iran, as demonstrated during ‘Saddam's war against Iran, when the United States, the Soviet Union, and Nato allied together to break Iran down, but they could not because the religious faith of the people defeated them’.Footnote 36

Another important narrative trope is Iran's respect for women's rights, as mandated by Islam.Footnote 37 According to Khamenei, in the West the commercialization of women's body is presented as emancipationFootnote 38 but, in reality, the ‘Western gaze’ reduces women to objects, while Islam upholds their dignity. One of Khamenei's posts on this topic is accompanied by an image symbolizing a woman working in many sectors of life, from minding children, cleaning, and cooking, to paid employment.Footnote 39 In this image, the woman is negatively affected by too many heavy burdens. It is a situation of ‘slavery’,Footnote 40 Khamenei argues, resulting from the West's idea of emancipation, which is at the service of capitalism and patriarchy. In another post, Khamenei explains that Western feminists and capitalists pushed women into the labour market to have cheap workforce.Footnote 41 According to the Supreme Leader, this process distracts women from their primary role as mothers and wivesFootnote 42 and promotes the idea that sexual behaviour should be unregulated. This resulted into men having sexual satisfaction whenever they desire it at the expenses of women, and into a general ‘moral corruption’, as evidenced in the legalization of homosexual relations – something that all religions prohibit, not only Islam, Khamenei argues.Footnote 43

Political and systemic superiority

The moral superiority of Iran translates into the superiority of its policies and political system. Liberal democracy is criticized, while the Islamic Republic is celebrated as more complete as it is based on both democratic and religious values.Footnote 44 Furthermore, liberal democracy is rigged by the interests of single political parties, which transform electoral competitions into struggles for power, instead of working for the common good.Footnote 45

The political superiority of Iran also results from its commitment to resist imperialism. In this discursive frame, Suleimani's legacy is mobilized to celebrate Iran's strategic and political achievements in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. On the anniversary of his killing, Khamenei describes the qualities of Suleimani (braveness, courage, responsibility, purity) and argues that they were forged in war and the revolution, as well as in his devotion to God.Footnote 46 According to Khamenei, the superiority of Iran is also demonstrated by the failed attempts of the United States at interfering in its internal affairs. To this, the West reacted by fabricating anti-Iran and Islamophobic propaganda, funding groups such as the Islamic State, and orchestrating internal revolts, such as the Woman Life Freedom uprising.Footnote 47 The issue of compulsory veiling, in particular, is discussed by Khamenei as an excuse to incite revolts, which aim at breaking Iran's independence rather than advancing women's rightsFootnote 48 – a message that the mediators convey to the far right entirely. Commenting on the expulsion of Iran from the UN Commission on the Status of Women in December 2022, the Embassy of Iran in Italy accuses other member states of hypocrisy, as they never ratified major international conventions for the protection of human rights.Footnote 49 The 1979 revolution has not only brought independence to Iran, but also improved the life of Iranians, including women's, Iran's state representatives – and the mediators – argue. During the Woman Life Freedom uprising, state propaganda has insisted that the revolution prompted women's emancipation through education and political representation.Footnote 50

Performative superiority

Iran self-brands as superior also in terms of technological, economic and strategic achievements. Iran's achievements are never celebrated against the progress made by other countries but, rather, against the difficulties that Iran had to overcome as an isolated country under sanctions.Footnote 51 Narratives of resistance as a demonstration of superior strength are central. Khamenei pushed them to the point that he thanked international sanctions for motivating Iranians to do more despite the circumstances,Footnote 52 demonstrating ‘the nation's strength’.Footnote 53 In this discursive context, hashtags #IranForte (Iran is strong) and #PossenteIran (Iran is powerful) have been used. Examples include Iran's successes in military defence and the disruption of ‘the enemies’ plans’ in reference to ‘the West's anti-Iran activities’;Footnote 54 Iran's success in cancelling the negative effects of sanctions;Footnote 55 Iran's achievement in the medical sector, an example of which is the Iranian anti-Covid19 vaccine.Footnote 56

Strategic superiority too is discursively constructed building the failure of Western policies in the region, a message that the mediators covey to their Italian audience. Khamenei argued, ‘the result of Iran's activism is the defeat of the United States in three countries. They wanted power in Iraq, but they do not have it; they wanted to overthrow the government in Syria but could not; they wanted to destroy Hezbollah and Amal in Lebanon, but they could not’.Footnote 57

A multipolar world order

These three discourses of superiority join together to form the second discourse of an emerging multipolar world order. This discourse exposes the decline of Western hegemony (not only, but mainly, American), its weakness and failure, and contrasts it against the success of countries such as Iran, Russia, and China.Footnote 58 In this discourse, failures of Western policies are reclaimed as successes of Iran, Russia, and China, but also as a consequence of a global Islamic Awakening. This is ‘an expression of the strength of faith, Jihad and trust in God’ and a ‘rejection’ of the ‘United States’ attempt at deviating the Islamic world from its path of awakening and happiness’,Footnote 59 observes Khamenei.

In 2022, Khamenei praised Putin as a strong leader and an important ally to Iran. Cooperation has to be reinforced, the Supreme Leader argued, to the benefit of the economy and self-defence against Nato's imperialist aggression.Footnote 60 This discourse outlines a larger international strategic vision, with new leaders and a multipolar international system. The growth of relations between Russia and China, for instance, is praised not only because of its positive implications for Iran, but also because of its potential to transform international politics.Footnote 61 According to Khamenei, the crisis of the West is creating a shift in world power in favour of Asia, which will become ‘the world's centre of science, economy and political-military power’.Footnote 62 A multipolar world is one of justice, the Supreme Leader states, and equality among the nations of the world. In an illustration of this, Khamenei argues that not only the United State will stop interfering in the domestic affairs of other countries, but that the praxis of installing military bases abroad, ‘making the poorer state paying for them’, will stop too.Footnote 63

The reception of Iran's authoritarian discourse

The dissemination of these two discourses in Italian and to an Italian audience is a deliberate act by Tehran, aimed at circulating state propaganda. It is, however, cultural and political entrepreneurs, or the mediators, who politicize and channel it to Italian far-right publics. Thanks to the richness of past and present connections, there is no shortage of mediators.

Echoing Rasheed (Reference Rasheed2022) and Gurol (Reference Gurol2023), this article argues that cross-border dissemination of authoritarian discourses and narratives contributes to the reproduction of authoritarian power, benefitting the receiving audiences who reinforce the legitimacy of their actions and ideas in the environments observed. The narratives coming from Iran are selectively translated by mediators in Italy and conveyed to Italian far-right networks. For example, references to Islam are de-centred in favour of references to Italian traditions and national identity, and narratives about the superiority of the Islamic Republic's political system are not picked up, in favour of an emphasis on the limitation of liberalism. Also, specific political junctures in Italy are of great importance to determine the re-framing of Iran's authoritarian discourse, as the mediators utilize specific topics in the public debate to strengthen the appeal of the discourse coming from Tehran.

The material examined suggests that Iran's authoritarian discourses and narratives resonate in the discourses diffused by mediators in Italian far-right networks in two specific discursive frames. The first is a discourse in defence of tradition. This has two dimensions. One is the immorality of liberalism as reflected in the hypocrisy of the West, with narratives about Western double standard regarding Palestine, Ukraine, and Italian history. The other dimension is anti-feminism and anti-‘gender ideology’, with narratives about the weakening of traditional gender roles and identities as a gateway to liberalism and neoliberalism, with specific references to the Italian public debate. The second discourse pivots on anti-Atlanticism and multipolarity, with attention to Italy's role in it.

The analysis shows that the far right receives, reproduces but also creatively reframes the content coming from Tehran, based on a logic of both interest calculation and ideological affinity. In other words, while Iran engages in authoritarian diffusion through its channels, the instrumental utilization of its official discourse may benefit the mediators and Italian far-right forces more than the Iranian state. In fact, while both build on Traditionalist values, the discourse of the Iranian state is not only adapted, but at times fundamentally changed and even radicalizedFootnote 64 by the mediators and the far right in Italy, with the goal of capturing the attention of the targeted audience and its authoritarian political imagination. Examples include how the Traditionalist and nationalist values uphold by Tehran are associated to fascist history and traditions, something the official representatives of the Iranian state do not suggest; and how the anti-gender and Transphobic discourse is associated to positions against the Covid-19 vaccine, a discourse which is popular among the Italian audiences that are addressed by the mediators while it is not among the representatives of the Iranian state. It follows that the mediators and their audiences seem to benefit from the authoritarian propaganda coming from Iran more than the Iranian state, as they use it to consolidate their authoritarian discourse. Instead, the Iranian state does not necessarily see new venues to expand its influence in Italy breaking open (Table 2).

Table 2. Italy's far right reception of Iran's authoritarian discourse

Against the liberal hegemonic order

Liberalism is immoral because it corrupts and alienates human beings from their traditional ‘natural’ identities. As described earlier, this argument is present in Iran's state discourse in general and in specific cases – such as women being alienated from their ‘natural’ role as mothers and wives – and is present in the far-right discourses and narratives, too.

Overlapping with Khamenei's discourse, the Shayk Abbas Di Palma, of the Imam al-Mahdi association, frames Islam as a bastion against political and cultural alienation. Islam is a ‘living religion’, which liberalism wants to eliminate to create ‘a universal and homogeneous world order […] where religion is nothing more than a phenomenon relegated in the past, with no relevance for today’.Footnote 65 While narratives presenting Islam as a defence of tradition are historically present in the far right, as discussed earlier, they usually are marginalized in favour of a larger and more political discourse in defence of traditions. Citing Terracciano, Hanieh Tarkian explains that liberalism is immoral because it wants to create ‘a single government (the New World Order), a single political, institutional and social system (liberalism), a single system of values (individualism-egalitarianism-the ‘human rights doctrine’) and a single lifestyle (consumerism) […] which enable the absolute power of […] the global financial elite’. To resist this threat, Tarkian argues, we must defend the peoples’ traditional identities and their right to self-determination.Footnote 66

Another narrative that resonates with Iran's state discourse presents liberalism as a dangerous ideology for Western and Italian audiences. In an event hosted by Le Dimore della Sapienza, titled ‘Chi ha paura del Natale? I musulmani oppure…?’ (Who fears Christmas, Muslims or…?), liberal hegemony is described as a double threat. According to the speakers, liberalism, on the one hand, endangers the traditional identity of Italy. On the other hand, it deflects negative public attention on religious minorities (Muslims) presenting them as those who threaten Christian and nationalist values. This is a narrative trope often mobilized by Khamenei too, who foregrounds how Islam respects all religion, instead. This line of thinking circulates in other platforms too. For example, Il Primato Nazionale defends Christmas as a foremost Italian celebration that the ‘liberal agenda’ attacks to ‘push Italians to give up their identity and embrace an amorphous and identity-less liberal globalization’.Footnote 67

Liberalism also informs Western foreign policy, the United States and Europe's in particular, as evidenced by their double standards when it comes to Palestine, Yemen, and Ukraine.Footnote 68 Narratives about these two countries largely overlap with Iran's official state discourse, as discussed earlier, although they are re-proposed in different forms, centring Italy as a victim of the same double standard along with Palestine, for example. During the event titled ‘Foibe, Palestina: due tragedie così lontane ma così vicine’ (Foibe and Palestine: Two distant yet similar tragedies) organized by Le Dimore della Sapienza,Footnote 69 the three speakers (all of whom are Italian) criticized liberalism and ‘the new world order’ for the silencing of the plight of both Palestinians today and Italians in Slovenia and Croatia at the end of World War Two. According to the speakers, who praised Iran for resisting Westernization, liberalism (which was one of the forces winning WW2) condoned violence against Italians in Slovenia and Croatia to weaken their nationalist pride and identity. While re-elaborated to resonate with specific aspects of Italian public debates and with the far right's perspective on Italian national history, Iran's state narratives about Palestine overlap with the Italian far right's nationalism in the form of a defence of nationalist identities from liberalism and its attempts at weakening them.

Anti-Feminism and anti-‘gender ideology’

Anti-feminism and, in its more recent iteration, anti-‘gender ideology’ are crucial elements in the contemporary rise of the global right (Norocel and Giorgi, Reference Norocel and Giorgi2022). The traditionalist-inspired reaction against intersectional feminism and against the critique of the gender binary rely on the naturalization of gender complementarity, which is at the core of both the Iranian state's and Italy's far-right traditionalist political discourse, as discussed earlier in the case of Iran. The magazine Fuoco dedicated a special issue, titled ‘Hanno ucciso l'uomo maschio’ (They killed the masculine man, 2021) to this issue, and during its launch, one of the contributors, Costanza Miriano,Footnote 70 talked about ‘the lies of feminism’.Footnote 71 According to Miriano, feminism convinced women to renounce their natural role as mothers and ‘become like men’. She talked about the difficulty to reconcile a professional career with motherhood because ‘the labour market does not consider us as mothers’, concluding that ‘we are not discriminated against as women; we are discriminated against as mothers’ and that ‘it is not important to help mothers to work, but to help workers to be mothers’. Overlapping with one of Khamenei's declarations examined earlier in this paper, Miriano said that ‘feminism is a politics with no resonance in the real life of women. We know that feminism is a top-down project funded by financial elites, who are interested in convincing women to work because they are paid less […] feminism wants to convince women that it is better to obey an employer than a loving husband’.

During the same event, Tarkian followed up some of Miriano's points, emphasizing that powerful liberal media elites hide ‘evident truths, such as that a child needs a mother and a father and that there is a natural correspondence between biological sex and being a woman or a man’.Footnote 72 Transphobic messaging is common in far-right circles and on the mediators' (Tarkian's and Milani Amin's) social media profiles. This reflects the importance of the specific context in determining discourses and narratives. While in Italy Trans people's identity and rights are under attack by conservative forces, making it a salient issue for attracting far-right audiences, in Iran sex reassignment procedures and consequent legal adjustments are supported by the state and are not contentious religiously, therefore they are absent from Iran's official discourse.

The obsession with ‘gender ideology’ is a characteristic of contemporary transnational right-wing populism. There is a consolidated language and set of topics that most of far-right forces refer to, when talking about this issue. However there are differences too, because, as argued by Anievas and Saull (Reference Anievas and Saull2022), the far right is ‘an internationally interconnected yet ideo-politically variegated global phenomenon’. Discursively, the far right in Italy presents gender as an ideology and utilizes a codified ‘anti-gender’ discourse. As discussed earlier, this is not present as such in Iran's state discourse, which is more focused on the defence of traditional gender roles and Islam, rather than fighting against ‘gender’ as a code for a broader anti-liberal discourse. An example of how the far right in Italy operates is provided by ideologue Diego Fusaro, who has often argued that ‘gender ideology’ is a threat that comes from the globalist elites, who want to establish the New World Order by uniformizing the world population into an identity-less and docile mass of consumers.Footnote 73 While the Iranian state does not engage in ‘anti-gender’ discourse, the political conclusion which the far right in Italy and the Iranian state reach, largely overlap, in their common anti-liberal and pro-gender complementarity persuasions.

Anti-Atlanticism and multipolarity

When it comes to anti-Atlanticism and multipolarity there seems to be a significant overlap between Iran's discourse and the far-right one, in how the passing of Western hegemony is exposed in favour of other, new emerging powers. Resonating with Khamenei's positions, Russia, China, and Iran are praised as ‘proud countries’ that defend their national identity and inspire a multipolar world order based on national sovereignty.Footnote 74 There also are differences, however, such as the role Italy plays in such a scenario.

Italy is in fact presented as a ‘frustrated hegemon’, which has the power and the ambition to dominate in the Mediterranean and beyond, but is disempowered by non-nationalist liberal elites, both Italian and foreign. Utilizing expressions such as ‘tornare potenza’ (make Italy powerful again), ‘mai piú schiavi’ (we will never be slaves again) and ‘mare nostrum’ (our sea), Il Primato Nazionale and Fuoco have dedicated significant attention to the analysis of how Italy can re-establish itself as the hegemon in Europe and the Mediterranean, fulfilling its historical role.Footnote 75 This analysis presents British geopolitical ambitions as in direct competition with Italy's, resonating with a geopolitical vision already popular within the far right. This analysis was popular during Fascism and survived thanks ideologues such as Evola, Dugin, Mutti, Terracciano and others (Piraino, Reference Piraino, Piraino, Pasi and Asprem2023). The negative role attributed to British ambitions is complemented by a negative view of American foreign policy, responsible for diffusing the liberal order – or ‘the New World Order’ – through imperial wars.Footnote 76 In this vision, Iran is seen as an ally in the resistance against Atlanticism.

Conclusion

This article has examined the reception of Iran's authoritarian discourse by the far right in Italy, discussing overlaps and differences. Arguing that the far right is interconnected globally but presents ideological and political differences locally, the study suggests that today, discursively, the Italian far right sympathetic to Iran places less emphasis on the defence of religion than it places on the defence of nationalism and national identity, approaching religion as just one expression of a nationalist identarian tradition (Graff and Korolczuk, Reference Graff and Korolczuk2022). Grounding this examination in specific historical trajectories and practices of agency, this analysis suggests that the forces examined aspire to the establishment of a large front oppositional to neoliberal globalization (or ‘the New World Order’) inclusive of actors that, bringing together Traditionalism and nationalism and regardless of religious differences, centre sovereignty as a value. In such a coming together, the authoritarian discourse hailing from Tehran is used by the local authoritarian actors to reinforce their discourse, which significantly overlaps with Iran's. While this paper cannot and does not demonstrate that the Italian far right ‘copies’ Iran's state discourse, it shows that there is a significant overlap between the two, which the paper centres as analytically significant in demonstrating how authoritarian discourses travel and diffuse transnationally. While the scholarship on authoritarian diffusion has traditionally centred the ‘sending’ state, focusing on its motivation and the measurement of the success of its diffusion activities, this paper shifts the perspective and focuses on the receiving audience and the ‘chain of transmission’ that enables diffusion. The analysis in fact shows that the local context plays an important role in determining the discursive overlaps and differences, as ‘mediators’ and far-right organizations are strategic about what discourses and narratives ought to be picked up to resonate with local publics and reinforce their messaging. In conclusion, the focus on discourses and narratives as immaterial resources for the diffusion of authoritarianism contributes to our understanding of how global connections between illiberal actors (both state and non-state) take form. In fact, narratives, norms and values advance transregional authoritarian links, reinforcing the discourse of both the sender state and the receiving side.

Funding

The research has been funded by Dublin City University's Research Initiatives Fund 2022.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Dr Rassa Ghaffari for her collaboration on this research and to the anonymous reviewers for their comments. Any errors that remain are my sole responsibility.

Competing Interests

The author declares none.