Hungary has gone through a de-democratization process since 2010. The right-wing populist government led by Victor Orbán and the Fidesz party built up a so-called hybrid regime within the EU (Bozóki and Hegedüs Reference Bozóki and Hegedüs2018; Filippov Reference Filippov2018). Hybrid regimes are in the ‘grey zone’ between democracies and complete autocracies. While democratic institutions formally exist, their contents are significantly damaged. Over the past decade, Fidesz has abandoned the rule of law, the role of the constitutional court and parliamentary work, and made a mockery of the system of checks and balances (Dostal et al. Reference Dostal2018). The scientific literature characterizes hybrid regimes as populist regimes (Castaldo Reference Castaldo2018; de la Torre Reference De la Torre2018; Wintrobe Reference Wintrobe2018) because they need to justify their systems and ‘explain’ their democratic cutbacks (see Robinson and Milne Reference Robinson and Milne2017). They build conspiracy theories against minorities, international elites and immigrants, with the promise to defend ordinary people and those belonging to the nation from all evil influences (Bozóki and Hegedüs Reference Bozóki and Hegedüs2018). The practical tools to achieve these goals include: occupying public and private media (Bajomi-Lázár Reference Bajomi-Lázár2013; Nagy et al. Reference Nagy and Peja2018) and using offensive governmental campaigns against the political opposition and minorities (Gall Reference Gall2016; Tóth Reference Tóth2021).

There are many consequences of populism in power (see Ruth-Lovell et al. Reference Ruth-Lovell, Doyle and Hawkins2019). Several scholars argue that right-wing populist rhetoric can strongly influence people's attitudes and values (Schmuck and Matthes Reference Schmuck and Matthes2017).Footnote 1 Permanent xenophobic and authoritarian populist agitation often lead to social polarization and exclusivist or non-solidarity attitudes towards ‘others’ (Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2017; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019), be they the poor, the Roma, the unemployed or migrants. This agitation can also change citizens' voting behaviour in favour of populist governments (Barna and Koltai Reference Barna and Koltai2019).

These attitudinal consequences are highly salient in Hungary. Prime Minister Orbán successfully took advantage of the 2008 global economic crisis and the so-called refugee crisis in 2015. Using conspiracy theories and xenophobic rhetoric in public media and other government-friendly outlets, Orbán stabilized and even increased the government's popularity (Barlai and Sik Reference Barlai, Sík, Barlai, Fähnrich, Griessler and Rhomberg2017).

In addition, the Orbán regime contributed enormously to the social and attitudinal polarization of Hungarian society. The new regime established a workfare system based on welfare populism (Kriesi Reference Kriesi2015), blaming the poor for their fate. In this illiberal workfare state, equality-based solidarity is replaced by the support of ‘deserving national groups’. The anti-poor social politics emerging after 2010 (Gábos et al. Reference Gábos, Kolosi and Tóth2016) became accepted among a significant part of society. It is no surprise that attitudes about who the state should support are extremely ambivalent (Juhász and Molnár Reference Juhász and Molnár2018). Inclusive solidarity declined dramatically between 2008 and 2016 in Hungary, while exclusive or non-solidarity attitudes increased radically (authors' own calculation, based on European Social Survey (ESS) fourth and eighth rounds).Footnote 2 However, there appears to be a consensus that Hungary should not support foreigners in any form. Surveys performed between 2002 and 2018 pointed to high levels of xenophobia compared to other European states (authors' own calculation). This change in attitudes and solidarity patterns consequently favoured only governmental political forces since they effectively addressed exclusivist groups after 2015 (Barna and Koltai Reference Barna and Koltai2019).

It is precisely these political and attitudinal changes in Hungary which excited our interest in this research field. We aim to identify and characterize different solidarity groups in this populist hybrid regime. Our research is based on an explorative approach, giving individual-level explanations for attitudes regarding institutionalized solidarity (macro-solidarity) and inclusion/exclusion in times when populists are in power. We present how different solidarity groups' attitudes reflect and justify the regime's values and attitudes towards people in need and how certain solidarity types contribute to the regime maintaining and strengthening social and political polarizations in Hungary. We demonstrate how social positions, different levels of social attachments and the scope of solidarity and feelings of deprivation/appreciation, political trust/powerlessness and open-mindedness/authoritarianism drive formations of different types of solidarity in Hungary. Through this, we aim to contribute not only to political sociology but also to the emerging political science literature of political polarization and non-consolidation.

Our most important research questions are: (1) How does institutionalized (macro-)solidarity appear to people in need in a country captured by right-wing populist political forces? (2) Who belongs to different solidarity clusters, and why? (3) What political orientations can be linked to these solidarity groups? (4) Which groups' attitudes reflect the values propagated by the government? Finally, (5) How polarized is Hungarian society by its (solidarity) values?

Analytical framework

Before looking at the manifestations of solidarity, it is worth briefly clarifying our analytical framework and exposing how the Orbánian illiberal workfare regime contributes to Hungary's social and attitudinal polarizations.

First, giving an analytical frame for our topic concerning populism in power, we discuss our analyses within the populism and polarization approach (see Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2017), which focuses on the polarization/fragmentation of societies ruled by populist governments.Footnote 3 This approach includes investigations of social inequalities (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2018; Lakner and Tausz Reference Lakner, Tausz and Kuhlmann2016), exclusivist attitudes and tensions between political camps (Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015). It indicates that right-wing populist political forces in power prevail in political discourses in many European countries (Mudde Reference Mudde2016; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2015) and, often using captured media (Prior Reference Prior2013), they strengthen social and political polarization (Müller Reference Müller2016). Brutal political discourses and conspiracy theories go hand in hand with the spread of discriminative attitudes towards demonized groups such as those who sympathize with the political opposition, migrants, LGBTQ communities, poor people, the Roma, refugees and non-governmental organizations (Schulze et al. Reference Schulze2020).

Some crucial sociopolitical changes should be mentioned here as we turn to some concrete examples of how the anti-poor workfare regime works in Hungary. A vital labour market change was the introduction of so-called public employment by the Orbán government. Public employment is a unique form of employment status: unemployed people leave the registry for the period in which they have public employment. Public work is ‘compulsory’; rejecting it may result in losing social aid immediately and for up to three years. However, following the end of public employment, slightly more than 10% of the participants enter the primary labour market, and this rate has gradually been shrinking since 2011 (Cseres-Gergely and Molnár Reference Cseres-Gergely, Molnár, Kolosi and Tóth2014).

One of the most significant changes the Fidesz government introduced was the flat-rate income tax. This change significantly increased inequality since it primarily favours people with high incomes. The next meaningful change was the rise of the consumer tax (VAT) to 27%, which became the highest in Europe. Low-income families suffer considerably from this tax burden since it represents an elevated part of their total household expenditure (Markó Reference Markó2012). Further tax reductions and various state supports also contribute to the increase in inequalities: introducing income tax reduction for families with two or three children is not advantageous for families on low or no income.

With regard to migration policies, a pervasive system of support based on international standards existed in Hungary before the refugee crisis of 2015. However, it is essential to emphasize that due to changes in the government's migration and refugee policy, this system came to a halt after 2015. Even the Refugee and Migration Integration Fund, where non-governmental organizations could apply for EU funds, has been wholly suspended. It is no surprise, then, that today refugees are not only disfavoured but indeed unable to enter Hungarian territory when they arrive from a safe third country, according to Hungarian legislation (Tóth Reference Tóth2021).

Looking at changes in attitudes, we can see that standards of moral and ethical values – including the importance of democracy – decreased in Hungary between 2009 and 2013. Social norms are permanently polarized and instrumentalized by political left–right identification (Keller Reference Keller2013). According to Juhász and Molnár (Reference Juhász and Molnár2018), the government's exclusive and anti-poor sociopolitical measures have gained support within the population, as reflected by: macro-solidarity attitudes concerning state support for older people, large families or unemployed people, and agreement with the statement that ‘government should reduce differences in income levels’ decreased significantly between 2009 and 2017.

Regarding anti-migrant sentiments, governmental xenophobic propaganda campaigns led to moral panic and exclusivist attitudes in Hungarian society after 2015. Conflating asylum-seekers, economic migrants and terrorism (Bocskor Reference Bocskor2018), moreover, the image of a ‘righteous protector of Christian European civilization’ and the demand to exclude ‘polluting migrants as human waste’ from the national territory (Thorleifsson Reference Thorleifsson2017) led to support for Fidesz (Barna and Koltai Reference Barna and Koltai2019). According to Barlai and Sik's (Reference Barlai, Sík, Barlai, Fähnrich, Griessler and Rhomberg2017) longitudinal study, due to the government's anti-migrant campaign, xenophobia reached a peak in 2016 in Hungary. Besides, welfare chauvinism also hit a record: 82% said that refugees were a burden on Hungary because they took jobs and social benefits (Barlai and Sik Reference Barlai, Sík, Barlai, Fähnrich, Griessler and Rhomberg2017). These results can be confirmed by the cross-time data of Political Capital (2018), where a dramatic rise in the level of welfare chauvinism became evident between 2015 and 2017.

Research design

We present theoretical clues to demonstrate how social solidarity towards social and cultural minorities in need manifests in public thinking and how solidarity can be linked to social memberships, worthiness and welfare chauvinism.

First, the literature has consistently found that, in considering attitudes regarding solidarity, most respondents in Western welfare states rank social groups by levels of worthiness, where older people deserve the most, the sick and the disabled less, needy families even less, and the unemployed the least (Oorschot Reference Oorschot, Oorschot, Opielka and Pfau-Effinger2008: 269). Studies that add immigrants to this list find that they are considered the least deserving. While numerous interpretations exist for these highly consistent findings, what is certain is that they do coincide with the chronological order in which state-funded social protection was introduced to support the respective groups (Kluegel and Smith Reference Kluegel and Smith1986). Another strand of research focuses on the foundations of solidarity. This approach, among other things, examines whether people utilize individualistic explanations as foundations for their attitudes towards social inequality or not. It has been shown repeatedly that respondents who rely on such explanations (such as scapegoating or blaming people in need) tend to be less supportive of welfare spending and social protection of the poor or people in need (Kluegel and Smith Reference Kluegel and Smith1986). This heuristic is a close relative of the ‘culture of poverty’ concept born in the 1970s that claims, for example, that the value system of the poor contributes to the perpetuation of poverty (Lewis Reference Lewis1969).

Second, we present here theories concerning the migrant–solidarity nexus. Prominent economists argue that migration – the entry of a new labour force into the ageing European labour market – could have a long-term beneficial effect on European welfare states (Zimmerman and Bauer Reference Zimmerman and Bauer2002). However, several scholars argue that migration might reduce social spending (Alesina and Glaeser Reference Alesina and Glaeser2004) in the affected states. Even if it does not lead to an actual decrease in state redistribution, it is widely accepted that migration erodes social solidarity and the welfare state (Shayo Reference Shayo2009). This claim is generally supported by a historical argument: that the development of welfare states has its roots in the era of nation-building, where the distinction between ‘strangers’ and ‘members’ has become the primary criterion for redistribution regimes (Goldschmidt and Rydgren Reference Goldschmidt and Rydgren2018; Marshall Reference Marshall2009). As Will Kymlicka (Reference Kymlicka and Tierney2016) put forward, the welfare state is not rooted in universal humanitarianism but in social membership. This erosion of support might play out in several ways. One possible consequence, labelled the ‘anti-solidarity effect’ (Roemer et al. Reference Roemer2007), would mean an overall decline of support for welfare spending among the electorate once the ethnic composition becomes more heterogeneous. A much more broadly researched outcome is welfare chauvinism. Welfare chauvinism refers to the belief that migrants receive an unfair share of welfare spendings (Goldschmidt and Rydgren Reference Goldschmidt and Rydgren2018). This distinction between anti-solidarity and welfare chauvinism allows for a more complex picture to depict the migrant–solidarity nexus.

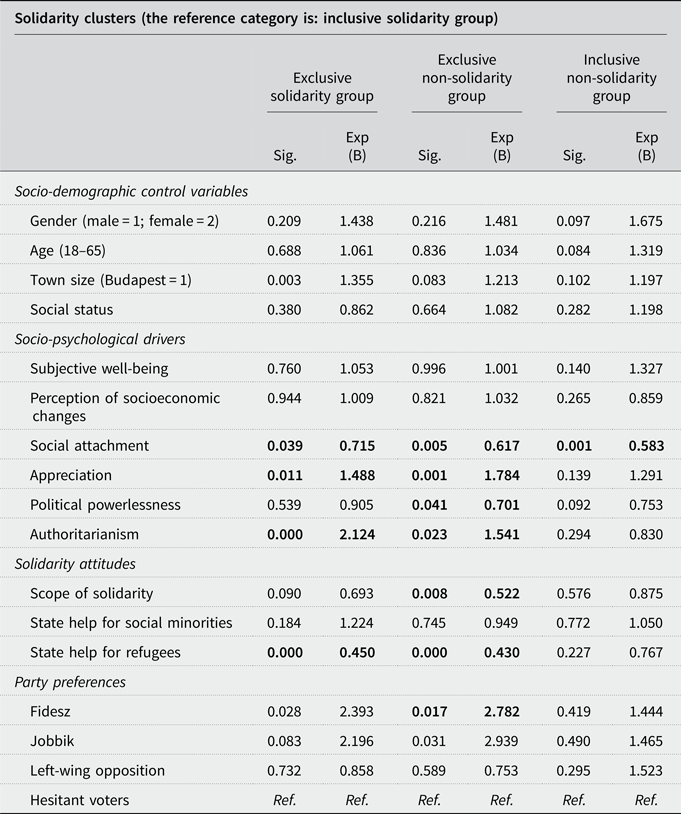

Using Kriesi's (Reference Kriesi2015) solidarity typology, we can summarize and better understand the phenomena mentioned above, namely the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion and attitudes to welfare redistribution. He differentiated inclusive solidarity, neoliberal multiculturalism, welfare chauvinism and neoliberal nationalism (Figure 1). Kriesi adds that a variation of welfare chauvinism, welfare populism, should also be discussed, an exclusive solidarity attitude that would exclude the undeserving poor from redistribution.

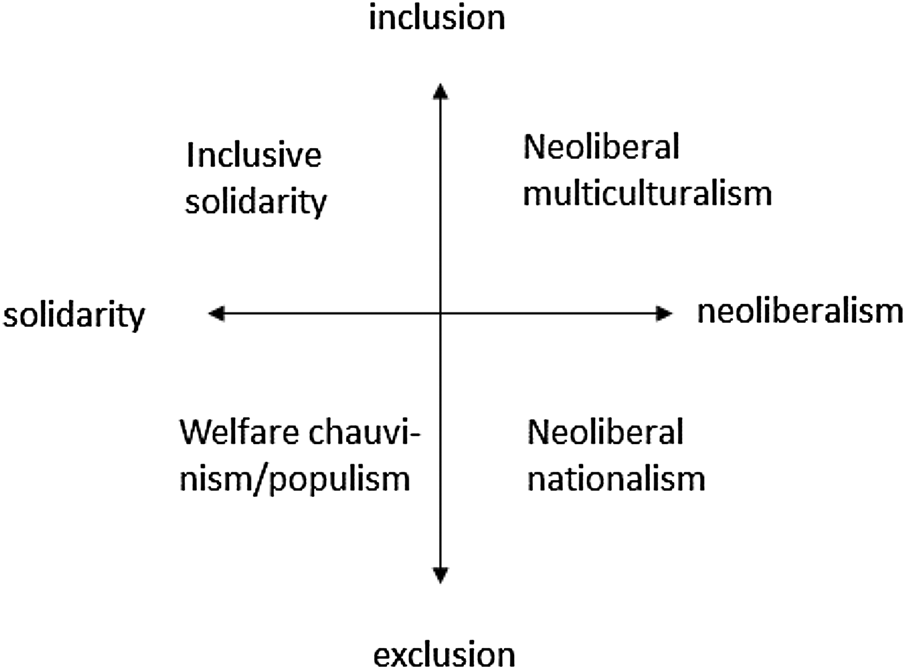

For the purpose of the present research, we rely on the dimensions identified by Kriesi; nevertheless, we deviate from the labels he used. This deviation is justified since Kriesi's labels – such as neoliberal multiculturalism – are value-laden and contain potential explanations for the researched phenomenon. (Furthermore, we think that the opposite of neoliberalism is, in fact, socialism rather than solidarity.) As a starting point, we share his approach to establishing the solidarity/non-solidarity dimension on the one hand and the inclusive/exclusive dimension on the other. We also believe that our data set can measure the existence and distribution of such approaches in the researched population. However, regarding the model labels, we think that they should be descriptive rather than explanatory from the start (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Modified Kriesi's Model

As we will discuss later, we operationalized the solidarity–non-solidarity axis based on macro-solidarity. This is important since what we are interested in is not everyday sociability but attitudes towards institutionalized forms of solidarity, such as the welfare state or international redistribution. Macro-solidarity is a form of solidarity that is based on the interests of others, such as supporting the struggle of minorities in other countries too. Macro-solidarity aims at ‘improving the situation of people who exist outside the horizon of personal interests’ (Bierhoff Reference Bierhoff2002: 295) and is motivated by values, norms or ideals that can be potentially violated and create feelings of moral obligation to aid others.

Macro-solidarity also refers to the support of the welfare state as an institutionalized form of solidarity. In this case, society acts as a community that shares certain risks (Bayertz Reference Bayertz1998: 37). How different goods and risks are shared and distributed among society's members (through taxation, social services, etc.) is subject to political struggles. Societal solidarity or ‘society-wide’ solidarity (Laitinen and Pessi Reference Laitinen, Pessi, Laitinen and Pessi2015: 9) could therefore be considered as a special form of group-solidarity.

Regarding the second axis – that is, inclusive and exclusive attitudes – our principal component that measures their existence was created on the basis of four subcomponents: welfare chauvinism, xenophobia, ethnocentrism and social dominance orientation. These components merit further explanation.

First, the massive changes in the welfare systems have produced a new wave of welfare chauvinism (Hentges and Flecker Reference Hentges, Flecker, Peter and Susanne2006: 140). Welfare chauvinism originally came from the new right in Scandinavia, whose parties first protested higher taxation and excrescent bureaucracy. This then became linked to sociocultural conflicts and the issue of immigration (Rydgren Reference Rydgren and Decker2006: 165). Media and right-wing populists interpreted this issue as an ethnic problem that reached the centre of societies and blamed refugees, aid organizations, social democrats and immigrants as responsible for society's social problems (Rydgren Reference Rydgren and Decker2006: 168–172). Christina Kaindl emphasizes that this attitude is extended to disabled people, the unemployed, other inactive people or even ethnic minorities in need and that it characterizes the middle of society (the politically moderate majority) and even trade union circles too (Kaindl Reference Kaindl, Bathke and Spindler2006: 72).

Second, an important approach is the theory of symbolic interests concerning ethnocentrism and nationalism. Of course, leaders and symbols are essential markers of identity that right-wing populist parties propose to people as a substitute form of integration, but there are more aspects to it. Nationalism and ethnocentrism, for example, are also key elements in identity formation. Referring to national pride is one way to stereotype the in-group positively and, therefore, provide a defence mechanism against other social losses (Lubbers and Scheepers Reference Lubbers and Scheepers2000). The individuals' response to being threatened confirms their real or imaginary group affiliation based on growing exclusive solidarity.

Concerning xenophobia, prejudice against immigrants or ‘everyday racism’ refers to negative attitudes towards foreigners because they are perceived as an (economic or cultural) threat (De Witte Reference De Witte1999). These negative attitudes play a crucial role in ethnic competition theory. This theory combines conflict theory (Campbell Reference Campbell1967) and social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979). Conflict theory states that social groups have conflicting interests because relevant material goods (employment, housing, social security) are scarce. This scarcity promotes competition. Consequently, autochthonous respondents lacking essential resources develop negative attitudes towards immigrants, making them susceptible to the appeal of right-wing populist parties and their exclusive solidarity-based politics.

Finally, the social dominance orientation theory examines people's egalitarian and exclusivist hierarchic views (Pratto et al. Reference Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth and Malle1994). Within their own group, the inclination to the social sub- and super-ordination (inferiority–superiority) approach determines whether people support political programmes aiming to maintain social differences or ones that promote equality. The social Darwinist, racist concept of the social dominance orientation often appears as a perception of culture-based differentiation. As a lifestyle seen as ‘superior’, culture and traditions are undermined by immigrants and other cultural or social minorities.

Explanatory factors

Our investigation's central research question is how solidarity works within a hybrid regime, and which explanatory factors, such as socio-psychological drivers, values and attitudes, drive it.

We built economic factors into our analysis to control for the effects of the socioeconomic changes in the past decade (see Baughn and Yaprak Reference Baughn and Yaprak1996; De Weerdt et al. Reference De Weerdt and Flecker2007). By including social status, perceptions of socioeconomic changes and subjective well-being, we could investigate both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ manifestations of economic considerations.

As psycho-social drivers, we have identified collective relative deprivation and authoritarianism as aspects for our research to investigate. According to deprivation theories, the danger of social and cultural deprivation is that some people find it hard to face the challenges generated by the accelerating world and rapid social changes. Feelings of competition – for example, with migrants – might be expected to be stronger if a person thinks their job is threatened or has suffered income or status loss. Deprived persons are, in this sense, more likely to hold unfavourable attitudes towards out-groups. The claim for national closing can be seen as an ‘identity stabilizing tool’ to counterbalance such feelings of insecurity, providing a well-deserved, calculable economic position and order in society (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Linder and Köti1998).

Authoritarianism was first investigated as a possible explanation for the surprising over-representation of blue-collar workers in the NSDAP electorate in Germany in the 1930s (Adorno et al. Reference Adorno1950), but it has come a long way since then. In the present research, an authoritarian personality is perceived as a combination of a need for submission and a need for domination. According to Ignazi (Reference Ignazi2000), social groups going through an identity crisis appreciate a clear hierarchy, well-defined social borders, order and a homogeneous society by excluding non-conventionalists from the solidarity community.

To analyse cultural factors, we measured feelings of social attachment and political powerlessness in our research. Regarding social attachment, the literature often addresses more general and long-term socioeconomic changes such as ‘individualization’, in which traditional societal institutions – such as the family or the occupational group – lose their former protective function. This may lead to social isolation, insecurity of action and anomic conditions that can be targeted by the exclusivist policies of right-wing populism (Heitmeyer Reference Heitmeyer1992). Therefore, the willingness to share appears to diminish with a greater social and ethnocultural distance between groups (Goldschmidt and Rydgren Reference Goldschmidt and Rydgren2018). On the other hand, intergroup contacts can moderate these effects (McLaren Reference McLaren2003; Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew1997).

Second, according to the theory of political dissatisfaction and protest voting, people affected negatively by socioeconomic changes may become dissatisfied and feel they do not influence political processes. The attitude of political dissatisfaction means that voters do not expect anything positive from moderate powers, so instead vote for populist parties (Van Der Brug et al. Reference Van Der Brug, Fennema and Tillie2000). Mauk (Reference Mauk2020) found that populist parties' success might increase political trust among the electorate. But according to her findings, this is only valid in defective democracies (characterized by weak corruption control, illiberalism, etc.).

While establishing models that explain belonging to a certain solidarity group through the previously described dimensions, our aim goes further than that. We also want to understand the link between the solidarity groups and the willingness to support cultural and social minorities, such as refugees, Roma or unemployed people, as degrees of inclusiveness on the one hand and political orientation on the other hand.

First, support for state help to refugees is a contested area. ‘The idea of a general fraternity of all human beings, as well as the postulate deduced from that each individual is morally obliged to help all other individuals without differentiation, seems to overtax the moral capability of most human beings’ (Bayertz Reference Bayertz and Bayertz1999: 3–28). The idea of universal solidarity can be grounded in the idea of equality. Rather than being about solidarity with every human, it is more about solidarity with each human, based on the idea that all of humankind shares the same rights and duties (Laitinen and Pessi Reference Laitinen, Pessi, Laitinen and Pessi2015: 10).

Second, regarding the question of support for state help for disadvantaged social minorities: forms of solidarity that are based on ethnic boundaries can clearly be seen in political phenomena such as the ‘national preference’ (De Koster et al. Reference De Koster, Achterberg and van der Waal2013; Lefkofridi and Michel Reference Lefkofridi and Michel2014). Jobbik and some movements in Hungary, for example, actively engage in support actions for the poor but limit their help to the Hungarian ethnic in-group, while they strongly discriminate against the Roma. Fidesz favours those who have already ‘proven’ their willingness to come forward based on the logic of social dominance, excluding the ‘undeserving’ poor.

Third, the scope of solidarity points to the degree of its inclusiveness. It combines the idea of Laitinen and Pessi (Reference Laitinen, Pessi, Laitinen and Pessi2015: 7–12) – who differentiate solidarity on different societal levels: community-level solidarity, society-wide solidarity and solidarity of the entire humanity – and Stjernø's (Reference Stjernø2005: 16) aspect of the formation of solidarity on a ‘continuum’ of the self and its identification with others.

Finally, we also included voting behaviours in our research as these would help us investigate the link between ‘demand-side’ and ‘supply-side’ explanations of solidarity in a hybrid regime.

Data and methods

This article is based on the SOCRIS (Solidarity in Times of Crisis) survey conducted in Hungary (N = 1,000) between July and September 2017, a time close to the parliamentary elections.Footnote 4 The survey was based on a representative sampling of working-age employed and unemployed people. Our data are representative of gender, age-categories, level of education and degree of urbanization among employed and unemployed people aged between 18 and 65 years. We created the four options of solidarity based on our modified version of Kriesi's model by k-means cluster analysis and characterized them by compare-means analyses and a multinomial logistic regression model.

Creating solidarity typologies (dependent variable)

Solidarity–non-solidarity axis

As described previously, we established the solidarity–non-solidarity axis by measuring macro-solidarity. Macro-solidarity was operationalized in our questionnaire as supporting international and national redistributions and equality.Footnote 5

Inclusive–exclusive axis

Based on the scientific literature, we could identify some large groups of exclusivist attitudes: these include welfare chauvinism,Footnote 6 xenophobia,Footnote 7 ethnocentrismFootnote 8 and orientation on social dominance.Footnote 9 Based on these attitudes, we created a secondary principal component for setting up the inclusive–exclusive axis. Using the above two operationalized axes (solidarity–non-solidarity and inclusive–exclusive), we first created a cluster-variable with four attributes: inclusive solidarity, exclusive solidarity, inclusive non-solidarity and exclusive non-solidarity. In the multinomial logistic regression, we used this cluster-variable as the dependent variable, where the inclusive solidarity cluster was the reference category.

Explanatory variables

Economic factors

First, we used a principal component for objective social status offered by Lenski: present/last occupational position, education and income per capita (Lenski Reference Lenski2013). Regarding socioeconomic changes, we used variables by combining work activity and changes in workload and feelings of job security and unemployed people's perceived probability of being employed to measure perceptions of socio-economic changes among the working-age population. From these variables, we created an index. To measure subjective well-being, we created a principal component by using subjective income, changes in the family's financial situation in the past, and expectations concerning changes in the family's financial situation in future years.

Psycho-social drivers

Important drivers of exclusivist orientations are collective relative deprivation (CRD) and authoritarianism, measured by principal components. To measure CRD we used variables such as feelings of being appreciated, being rewarded for their efforts and feeling that their interests are protected on a group level.Footnote 10 To measure authoritarianism, recent theory and measurement instruments now draw upon three dimensions (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1988): conventionalism, authoritarian submission and authoritarian aggression. This is the approach we adopted from the theory of psychological interests in this research.Footnote 11

Cultural/political factors

To measure social attachment/identification, we used a principal component analysis, including ties with relatives, neighbours and the country, while the political powerlessness principal component contented variables measuring political disillusionment and feelings of lack of influence on political occurrences.Footnote 12 For political orientations, we used a variable measuring voting behaviour of the respondents, that is, which party would they vote for if political elections were to be held.

Solidarity attitudes

Our operationalization concerning support for state help for disadvantaged social minorities contained variables such as whether the state should help more to improve the situations of the long-time unemployed, people on a small pension or those with many children (principal component). To measure support for state help for refugees, we used a single variable as follows: ‘the state should help less/same level/more to improve the situation of refugees’. The scope of solidarity was measured by a principal component created from variables such as concern about the living conditions of their own family, of people in the neighbourhood, in the region, fellow countrymen, Europeans or people living in other parts of the world.

Results

Based on our modified Kriesi's model, we could differentiate four clusters along the inclusive–exclusive and non-solidarity–solidarity axes: the inclusive solidarity cluster, the exclusive solidarity cluster, the exclusive non-solidarity group and the inclusive non-solidarity group.Footnote 13 Analysing the data, we found the following cluster-proportions: 19% of the sample belonged to the inclusive solidarity group in Hungary, while the exclusive solidarity cluster percentage was 38%. The proportion of the exclusive non-solidarity group was 23%, while the inclusive non-solidarity cluster ratio was 20%. Figure 3 shows the k-means cluster analysis results and the average values of the axes in the floating columns: grey positive values mean more inclusiveness, while black positive values more solidarity (and conversely concerning negative values).

Figure 3. Solidarity Clusters

Differences between the four clusters

According to the results of the bivariate comparison of means analyses, the inclusive solidarity group members hold high social status, they are open-minded (non-authoritarians), and they can be characterized by the highest scope of solidarity and the highest level of social attachment. Still, they show strong subjective and collective deprivation and political disillusionment. In addition, left-wing voters (47%) and social minority and refugee supporters (29%)Footnote 14 are over-represented among this group.

The inclusive non-solidarity cluster is similar to the inclusive solidarity group concerning social status, open-mindedness, the scope of solidarity, social minority and refugee support, and political orientation. Still, this group shows higher levels of subjective well-being compared to the average.

The exclusive non-solidarity group can be characterized by average status, but those with the highest subjective well-being and levels of feeling appreciated (the opposite pole of collective relative deprivation) feel that they are the ‘winners’ of the socioeconomic changes. They are predominantly Fidesz voters (60%) and demonstrate unconditional political trust. Those who would give less state support to social minorities and refugees (68%) are over-represented among them, and they have the lowest level of solidarity.

To the exclusive solidarity cluster belong those with the lowest social status, mainly those living in smaller settlements. They feel like ‘losers’ of the socioeconomic changes and are less socially attached, but they feel appreciated; moreover, they are the most authoritarian among the investigated clusters and are over-represented among Fidesz voters (63%). Although their majority would give more support to social minorities, this group's decisive majority would provide less support to refugees (64%).

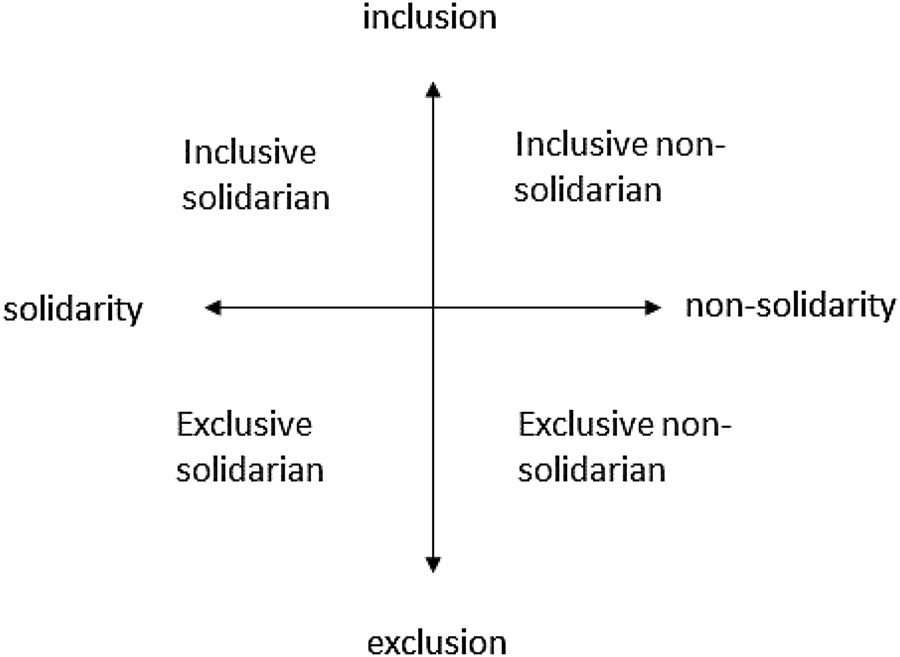

Next, we used a multinomial logistic regression model to explain the cluster classifications, where our cluster-variable was the dependent variable, and the inclusive solidarity group was the reference category (McFadden: 0.17; Nagelkerke: 0.39). Analysing the final model, we find that:Footnote 15

• Members of the inclusive non-solidarity group have significant lower social attachment levels (expB: 0.6); otherwise, they are similar to the inclusive solidarity group.

• Respondents belonging to the exclusive solidarity group live in smaller settlements (expB: 1.4), feel more appreciated (expB: 1.5), are more authoritarian (expB: 2.1), but less socially attached (expB: 0.7). Besides, they reject refugees (expB: 0.4) compared to the inclusive solidarity group.

• Members of the exclusive non-solidarity group also feel more appreciated (expB: 1.8) and exhibit more political trust (expB: 1.4), but they are authoritarian (expB: 1.5), have a narrow scope of solidarity (expB: 0.5) and are poorly socially attached (expB: 0.6). It is no surprise that they also reject refugees (expB: 0.4) compared to the inclusive solidarity group.

Furthermore, our logistic regression model shows an interesting interrelation between cluster membership and voting behaviour.Footnote 16 The model first calculates the probability of relations between ‘hesitant voters’Footnote 17 and voters of different parties within each cluster. These odds are then compared between the clusters. Our results show that the probability of voting for Fidesz within the exclusive solidarity group is roughly 2.4 times as high as within the inclusive solidarity group. What is more, this probability is some 2.8 times as high within the exclusive non-solidarity group as within the inclusive solidarity group. This means that the lure/attractiveness of the Fidesz party is much higher among exclusivist groups than among the inclusive clusters.

We have seen the political orientations of our clusters above. Now, let us examine the following figure, where we present the structure of different political camps by different forms of solidarity.

According to Figure 4, primarily inclusive groups constitute the symbolic political community of the left-wing opposition, but this community has become relatively depleted recently in Hungary. In contrast, as a far-right populist political force having a two-thirds majority in the parliament, Fidesz can principally rely upon exclusive solidarity and exclusive non-solidarity groups (74% combined). These groups constitute the most crucial recruitment bases of the governing party; therefore, this majority needs ‘to be addressed’ by charisma-based, scapegoating, welfare chauvinistic/populist and ‘closing-in/ethno-nationalist’ slogans. Namely, exclusive groups can be characterized not only by political trust and appreciation but also by strong authoritarianism, poor social attachments and a narrow scope of solidarity, and above-average far-right attitudes (as xenophobia, welfare chauvinism, social dominance orientation and ethnocentrism). For Fidesz, an effective and successful political campaign is practically impossible to achieve through the use of emancipatory and inclusive buzzwords. What is more, by using well-established exclusivist slogans, Fidesz can address one-third of the left-wing camp as well.

Figure 4. Proportions of Solidarity Clusters within Different Political Camps

Discussion

We investigated different solidarity types in times of populism in power. As we found, the inclusive solidarity group's proportion of the population is the lowest among the investigated clusters and, first and foremost, Hungary is clearly dominated by exclusive (and far-right) orientations and solidarity groups.

Political polarization, social positions, different levels of social attachments and the scope of solidarity and feelings of deprivation/appreciation, political trust/powerlessness and open-mindedness/authoritarianism play essential roles in forming different types of solidarity in Hungary. We can interpret these highly interrelated factors in a complex explanatory frame, including supply-side approaches.

Concerning political and attitudinal polarization, exclusive solidarity and non-solidarity are clearly over-represented within the right-wing populist camp, while inclusive groups are predominant among voters for the left-wing opposition. The political and communication strategies as ‘supply-side’ tools of the government matched the ‘demand-side’ attitudes of the exclusive solidarity and non-solidarity groups. Welfare chauvinism, xenophobia, ethnocentrism and social dominance orientation against all kinds of perceived out-groups are crucial attitudes that are shared by both the government and the exclusivist groups. Anti-poor social policy and agitations against non-existent enemies and, at the same time, inciting authoritarian reflexes by the government were tools that combined highly effectively to attain the strongly authoritarian exclusive majority, with the promise of restoring security and order in a supposedly ‘threatened’ country. The claim of heavy-handed solutions to enable freedom from ‘threatening out-groups’, and feelings of belonging to the ‘deserving’ (national) in-groups could result in feelings of appreciation and satisfaction with and strong trust in the ruling regime within the exclusive clusters.

Between the attitudes and drivers of the two exclusivist clusters, we can observe differences, however. First, the exclusive non-solidarity group focuses only on its own, tight, winner in-group and – based on a neo-conservative logic – would not give state help to any people in need (blaming the poor). Poor social attachments and a narrow scope of solidarity combined with selfishness and feelings of deservingness/esteem can lead members to perceive that they belong to an exclusive-superior group. This group reflects the government's neo-conservative intentions, creating a so-called ‘national-capitalist elite’ and a national (upper) middle class by bottom-up redistributions, a flat-tax regime and other state support.

Second, although the exclusive solidarity group's majority would support social minorities – such as older people, large families and unemployed people in need – they refuse to help refugees. Weaker social positions, more rural background combined with poor social attachments and a narrow scope of solidarity can lead members of this group to tribalism. It means that these group members feel secure in closed-in and charisma-based political circumstances, where ‘natural Hungarian (small) communities’ are glorified. They can feel that their in-group is a highly valued one based on a folkish/nationalist ideology. Since the closing-in authoritarian regime offers folk-based nationalism as an identity-stabilizing tool in turbulent times, the exclusive solidarity group might strengthen its identity and social position by national preferences and ‘ethnic-based deservingness’.

In contrast, in the left-wing opposition camp, solidarity conceptions and the underlying explanatory factors underpinning these stances on solidarity are different. The majority (65%) of left-wing opposition voters belong to one of the inclusive clusters. They feel political powerlessness and collective deprivation despite their higher social status, open-mindedness and tolerant attitudes. Inclusive solidarity values are rarely shared by everyday political discourses of the leading media, political actors in power and the majority of the population – which, of course, can result in feelings of political disappointment and frustration. But this phenomenon is more complex. Relative deprivation can also sow a bad seed of apathy towards out-groups such as refugees. Concerning the willingness to give state support to refugees, we found that only 25–30% of both inclusive groups would give more support to refugees, while 30–40% of them would provide less support. Since deprivation can lead to feelings of insecurity and threats to identity, fears of terrorism and financial and cultural deprivation can also make inclusive groups receptive to the government's exclusivist slogans.

But in a society that is broken in half like Hungary, a pervasive fire-trench logic exists between value-groups and political camps. There is no question that the strong, supposedly irreconcilable tensions between exclusive and inclusive solidarity and non-solidarity groups can lead to (further) polarization and the disintegration of Hungarian society. What is more, both exclusive groups are poorly socially attached, strongly closed-minded and ‘tribalist/elitist’. In contrast, inclusive groups are politically mistrustful and disappointed, making social and political polarization even more acute in the country.

This polarization is not a real problem for the regime, however. The key to the success of a populist, hybrid regime is maintaining social and political tensions between a radicalized majority and a blameable minority. Fears, conflicts, permanent preparedness and paranoia vitalize the regime, making political consolidations impossible. Immersed in ongoing crises, the hybrid regime's survival is a viable scenario; otherwise, Orbán must establish a dictatorship and standardize the Hungarians' solidarity values.

Acknowledgements

Data for this article were obtained in the project ‘Solidarity in Times of Crises. Socio-economic Change and Political Orientations in Austria and Hungary’ (SOCRIS). The research is funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, Project Number I 2698-G27) and the Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the ANN (2016/1) funding scheme, Project no. 120360.

Appendix

Table 1. Parameter estimates, multinomial logistic regression, final model