1 Introduction

Mark Pincus, Chairman and Co-founder of Zynga, once publicly stated, “I [Zynga] did every horrible thing in the book just to get revenues”.Footnote 1 Zynga was an early pioneer of social games, founded in 2007, with a mission to connect the world through games. In the first quarter of 2018, Zynga reports having 25 million daily active users (DAU) and generating a profit of US$5.6 million.Footnote 2 This paper presents a virtual ethnographic case study focusing on Zynga Poker (ZP) to shed light on how social casino game elements shape youths’ experiences of playing poker on Facebook. Findings highlight the importance of understanding the legal and regulatory implications of this new gambling frontier, which inevitably adds a new layer of risk and ethical considerations.

The Oxford Dictionary defines social gaming as “the activity or practice of playing an online game on a social media platform”.Footnote 3 Social gaming encapsulates a number of diverse game genres including casino-style games, role playing games, adventure games, and puzzle games. Based on social design mechanics and typically generating revenue off a free-to-play (F2P) business model, which allows social gaming players to acquire and play the game for free of charge. However, players are encouraged to make in-game purchases of virtual goods and currency.Footnote 4

Casino-style games on social networking sites (SNSs) and mobile apps are one example of the global rise of gambling opportunities on the internet that has occurred over the past few decades. Social casino games are essentially the convergence between online (real-money) gambling and social (virtual currency) gaming and are currently unregulated. Primarily because it is not considered to be gambling according to various interpretations of the traditional legal coordinates of consideration, chance, and prize.Footnote 5 Worldwide, these games are estimated to have earned US$3.1B in 2017 and expected to reach US$3.2B in 2018.Footnote 6 The embedding of gambling-style games on mobile apps and within existing networks designed for social interaction adds a new layer of risk and concern for public health and risk regulation professionals. in North America, the current minimum age requirement to create a profile on many SNSs and engage in social gaming, of any kind, is 13 years. This low barrier to entry, alongside the lack of regulatory oversight, puts forth a particular concern for vulnerable populations, such as youth.

Gambling expansion is a public health issue.Footnote 7 Worldwide prevalence studies have consistently revealed that adolescents (13–17 years) and older youth (18–24 years) are participating in all forms of gambling, both government sanctioned and unregulated.Footnote 8 Meta-analyses examining the problem prevalence rates of gambling associated with young people provide evidence that 2–8% of both adolescents and youth are experiencing gambling-related harms, with another 10–15% being at risk for the development of gambling problems.Footnote 9 Documented risk factors include parental and peer group gambling, normalisation and social acceptance of gambling, gambling accessibility, lower income and educational levels, and unsafe provision of gambling.Footnote 10 Of particular importance for the analysis developed in this article is research indicating that many youths experiencing gambling-related harms report initiating gambling in their early years,Footnote 11 that social casino games can serve as a gambling “training ground” for youth to migrate their play over to real-money gambling,Footnote 12 and that youth who make in-game micro-transactions are eight times more likely to transition to real-money gambling.Footnote 13 Finally, research gives us a glimpse into the lived experience of youth social casino players. Precisely, that ZP is perceived as a form of “gambling-lite,” because their gameplay embodies similar experiential thoughts and emotions that players encounter when wagering with real money.Footnote 14

Youth have long been regarded as susceptible to risky health behaviours (eg smoking cigarettes, consuming alcohol, engaging in unsafe sex).Footnote 15 The embedding of gambling and gambling-like games into SNSs and mobile apps appears to increase this susceptibility, since there is a chance of lowering the age of onset for participation long before adolescents (13–17 years) are legally able to gamble in most jurisdictions. Additionally, the use of big data analytics for “personalization, targeting, profiling and matchmaking”Footnote 16 means that game operators can tailor the game experience and messaging that might be especially resonant with young players.

As articulated by Boyd and Crawford,Footnote 17 big data is “less about data that is big than it is about a capacity to search, aggregate, and cross-reference large data sets”. It is well understood in the casino industry that game analytics is big business, justified and touted as a way to provide better customer service and promote special offers to players,Footnote 18 and more recently, as the utopian promise to track spending and behaviour habits in the name of player protection.Footnote 19 Similarly, social casino game developers have the ability to gather large amounts of player engagement metrics (ie big data), and to react quickly to changes in the player base.Footnote 20 However, what makes social casino games different, is the operators’ ability to collect and link game behaviour to what players are also doing outside of the game (eg demographic details, online consumption habits, social networks, etc).Footnote 21

The digitisation of data gathered from games has been argued to be a form of surveillance.Footnote 22 As David Lyon articulates, surveillance is the focused, systematic, and routine attention to personal details for purposes of influence, management, protection or direction.Footnote 23 Gamification, big data and other popular social networking services have already captured the attention of surveillance scholars.Footnote 24 Highlighting that how companies collect, process, analyse and use data as a business strategy to generate revenues constitutes a form of dataveillance. Specifically, dataveillance is “the ability of reorienting, or nudging, individuals’ future behaviour by means of four classes of actions: ‘recorded observation’; ‘identification and tracking’; ‘analytical intervention’; and ‘behavioural manipulation’”.Footnote 25

In this work, I present a virtual ethnographic case study, focusing on Zynga Poker (ZP). The primary study objective was to identify and examine influences of the game design and intention of ZP that youth would be exposed to when playing poker on Facebook. Drawing from literature in surveillance studies,Footnote 26 I discuss the potential ethical and risk concerns for young players when social casino game developers use big data to tailor and modify social casino games with the goal to use personalisation technologies to “extract money from players in tiny increments, on a minute-by-minute basis… to massage the details of the game mechanics and content over time to improve profitability”.Footnote 27 First, I will detail the data and methods used for the study, followed by a description of the discourses embedded in ZP. Finally, I will conclude by arguing that ZP serves to: (a) both shape and divert public consciousness in ways that weaken public understanding of gambling and gambling-related harms; and (b) increase social acceptability and contribute to an overall discourse that gambling is a harmless form of entertainment with few risky consequences. It should be noted that online privacy and regulatory oversight varies according to jurisdictional location. While my virtual ethnographic journey took place in Canada, findings have an impact on jurisdictions across the globe interested in understanding the environmental context that surrounds social casino games, particularly with respect to the protection and prevention of gambling-related harms to vulnerable populations, such as children and adolescents.

2 Data and methods

The data from this work comes from my virtual ethnographic journey playing ZP (April–June 2013), as part of my larger doctoral study. I chose to participate fully in ZP as this allowed me the opportunity to identify and examine the influences of the game design and intention of the poker application, rather than to observe my participants playing poker in the ZP community. This interactional investigation was followed by other ethnographic techniques such as analysis of official ZP documents, visual analysis of the website images, and interviewing both key stakeholders and youth. This approach to understanding ZP allows examination from multiple individual perspectives, while also exploring the interplay between the individual and the socio-environmental context.

Specifically, the data set consisted of the extant texts and visual images found on the application. Extant texts refer to texts which the researcher has had no hand in shaping, and which provide opportunities to examine particular discourses to help explore, explain, justify, and foretell individuals’ actions.Footnote 28 With respect to the textual data, four of ZPs documents were analysed: About Us, Community Guidelines, Purchasing Terms of Service, and Zynga’s Annual Report 2014, along with the two main visual images of ZP (ie The Lobby and Poker Room; Figures 1 and 2). Game images were chosen as they set the stage by introducing the players to the gaming application and to what they will be exposed to when playing, while also illustrating how ZP actively frames poker on Facebook.

Figure 1 Screenshot of Zynga Poker’s main lobby (Home Page) (image captured from the author’s computer on 30 April 2013)

Figure 2 Screenshot of Zynga Poker’s poker room (image captured from the author’s computer on 30 April 2013)

I was embedded in the game as a regular player using fictitious profiles and sets of personal information (representing one male player and one female player). My ethnographic journey was captured using Screenflow, a video capture software, alongside the use of analytic memos during my gameplay sessions to encapsulate my experiences and observations. Analytic strategies include situational analysis of visual discourses,Footnote 29 and thematic analysis.Footnote 30 Ethics approval for the study was received by the Office of Research Ethics at the University of Toronto.

3 Framing the landscape – discourses of social connection, harmlessness, empowerment, and virtual consumerism

Discourse is the outcome of the interplay of language found in textual and visual images,Footnote 31 which contributes to the framing of whatever topic, object, or process is talked about.Footnote 32 Four discourses were constructed on the ZP site to frame social casino poker: social connection, harmlessness, empowerment, and virtual consumerism. Each will be elaborated below.

3.1 Social connection

Unsurprisingly, ZP emphasises the importance and prominence of social connections within the game. As clearly outlined in the application’s Community Guidelines, “Zynga games are a fun way to connect with friends and meet like-minded people”. ZP’s About Us document articulates that players “have the option to play at any table, meet new people from around the world or join friends for a game,” in addition to “interacting with other players by chatting, completing challenges and sending and receiving gifts”. Both documents represent the underlying assumptions that ZP is built upon.

Social connections discourse is reinforced with specific features directly constructed within the ZP application. The main lobby (as illustrated previously in Figure 1) highlights intentional elements that have been chosen to enhance social connections between players. For example, players can immediately see which one of their friends is currently playing poker and where within the game they are located. The large banners at the bottom of ZP’s main lobby and poker room pages offer free chips to players who invite Facebook friends to join. From the moment that players enter ZP, there are constant design features that allow players to see and connect with both poker “buddies” within the system and friends that are a part of their larger Facebook community.

Once players enter into the main poker room (as illustrated previously in Figure 2), there are two prominent social connection design elements: the dealer and the chat box feature. The poker table is located prominently in the centre of the image; the colours of the room are bold and eye-popping – demanding attention. At the top centre of the table is a female dealer. The female dealer’s gaze is focused as if she is looking directly through the screen at you, personally inviting you to take a seat and join in the game. Having a dealer is an important representation decision, as it helps the game application and the playing experience feel “real”, like you would feel if you were physically sitting down at the table in a casino. Her direct gaze offers the players an immediate connection into the game.

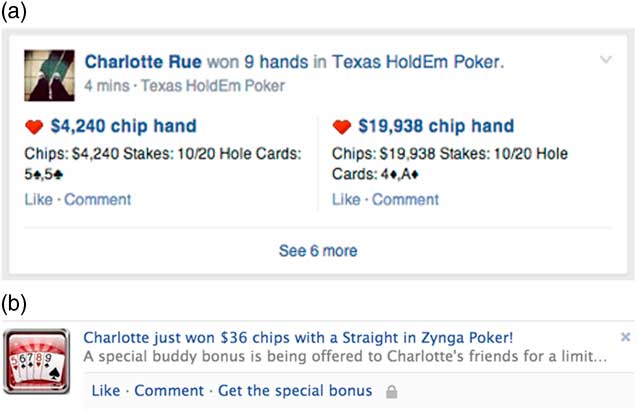

Finally, players receive invitations posted on their personal Facebook homepages by ZP, illuminating how ZP is using the networked nature of SNSs, along with the lure of extrinsic rewards, to motivate players to recruit new players (eg friends) to their games. For example, one invitation received promised “Get up to $10M chips for every friend that plays!” In essence, ZP is harnessing the power of social connections as an effective recruitment strategy and marketing tool. The blurring of lines between user-generated content and viral marketing illustrates significant ethical implications and challenges in regulating content to ensure adherence to Facebook’s advertising and marketing policies.Footnote 33

3.2 Harmlessness

The game of poker has “come a long way from cigar-store back rooms and dingy basements”,Footnote 34 finding itself prominently featured in the virtual lives of individuals on Facebook. However, the second discursive theme that I want to explore evokes old-time notions of poker and constructs ZP as a harmless game. As illustrated previously, it is my interpretation that the textual and visual images available on ZP are an example of how Zynga is actively framing poker as a social game between friends, as opposed to a form of gamblingFootnote 35 which would hold monetary (ie losing money/credits) and other risks (eg preoccupation with playing, spending too much time) for players. According to ZP’s About Us document, “Zynga Poker is the largest free-to-play online poker game in the world”. The very nature of the concept free-to-play may contribute to players perceiving their play as an innocent form of entertainment, implying a risk-free activity because no real money was wagered.

ZP is embedded within Facebook’s social networking platform. This, in and of itself, helps to construct the game as harmless. Facebook has become a taken-for-granted part of a daily online ritual for many, connecting itself directly into a player’s social world, despite privacy concernsFootnote 36 and potential related harms.Footnote 37 As a gambling scholar, I am aware that early exposure to gambling is a significant risk factor for experiencing gambling-related harms as an adult. However, many young people are not cognisant of this; as a result, participating in ZP on Facebook is void of any critical examination, particularly with respect to their own gameplay behaviours and marketing based on data-mining practices. Over the years, concerns about corporate surveillance of consumers to identify, classify, and assess consumer behavioural data for marketing purposes has long been discussed.Footnote 38 This can be particularly concerning, given that instead of having to be 18 years old to legally venture into the local casino or play on professional online poker sites, individuals are only required to be 13 years of age to create a Facebook profile and begin playing poker.

Within ZP itself, the game draws heavily on visual images, with minimal text (as shown above in Figures 1 and 2). It is this interplay between the two elements within the application that helps me analyse what might be going on discursively. At the top of the screens are arrays of other Zynga games that one can play, which are just a click away – all brightly coloured and cartoon-like. These cute images suggest harmlessness, drawing on discourses of carefree childhoods. By bordering ZP with other Zynga-affiliated games, they convey an overall image of fun and the animation exudes an element of innocence, reminiscent of many childhood games, despite some of the games’ more mature content that outside of Facebook would be regulated and age-restricted (see Figure 3). As shown on the banner, a game like Zynga Slots falls between non-gambling themes games, such as Farmville and Empires and Allies, while Lucky Play Casino resides alongside two other games (Citizen Crim and Villiage Life), both of which are also not based on traditional casino-type games. Embedding games based on traditional gambling-type activities alongside non-gambling type games is another example of deceptive marketing practices that helps to construct ZP, Lucky Play Casino, and Zynga Slots, as just another game within a repertoire of harmless gaming activities.

Figure 3 Zynga’s portal of games (image captured from the author’s computer on 30 April 2013)

Further, my analysis of ZP demonstrates a level of deliberate personalisation. Personalisation may be viewed as a way to enhance social connections within the application (as illustrated above), while also establishing trust. Personalisation within the game refers to the use of personal information, including real names, lists of friends, demographics, location, and more, as a means of personalising SNSs applications for a more tailored experience.Footnote 39 The uses of personalisation technologies have become widespread on SNSs and have increasingly been recognised as a key factor in instilling online trust and customer satisfaction.Footnote 40 When personalisation is used as part of a larger integrated engagement strategy, it has been shown to foster customer loyalty.Footnote 41 For example, immediately upon entering the application, ZP welcomes you by name and players can instantly see a list of their friends who are currently playing. Additionally, all communication, via email and/or posted onto one’s Facebook homepage, is personally addressed to the player by name.

3.3 Empowerment

The third discourse highlights an empowering frame, creating an environment where players feel more confident about their poker gameplay. Facebook has over two billion registered users,Footnote 42 and thousands of games to choose from, making it a player’s market. Therefore, games need to maintain a balance between skill and challenge throughout the entire lifecycle of the game.

ZP has strategically integrated a lot of design elements that relate to skill development and reinforcement for accomplishing certain in-game achievements. At the basic game level, players feel a sense of accomplishment as they win hands, play in tournaments, accumulate virtual chips, and build up Experience Points (XP). The images in Figure 4 illustrate how ZP enhances that sense of confidence and efficacy in one’s poker ability by posting mastery messages on a player’s FB timeline for friends to see and utilising pop-up windows and in-game notifications to highlight specific in-game poker accomplishments.

Figure 4 Empowerment messages (images captured from the author’s computer on 17 May 2013)

The achievements players attain, in comparison to fellow poker competitors, can also foster an empowered sense of self, and can be used to track poker play statistics to illustrate skill development over time. ZP captures detailed player data and profiles for every player. All profiles are made visible to fellow players by hovering over the player’s avatar. It is this player data that helps determine leaderboard standings and eligibility to play in tournaments, working as a reputational system that highlights trophies and personal standings. A player’s profile highlights a standard array of statistics, such as my best hand, number of hands won, highest chip level, and largest pot won, amongst other key variables. Competitiveness, whether it is against other players, or directed as a form of self-improvement, can significantly impact one’s confidence. This analytic profile page is designed as a retrospective tool for players to examine their own game highlights, in addition to helping to provide hand histories of players’ opponents.

3.4 Virtual consumerism

Selling virtual items for real money has become a lucrative business model in gamesFootnote 43 and is the final discursive theme. The virtual consumerism discourse reflects the increasingly common practice of infusing game mechanics with the consumption of items.

According to both Zynga’s annual report (2014) and their About Us document, “Zynga Poker has been a top 10 grossing game in the Apple App Store”. Documents also state, “Through the gift shop, players can personalize and decorate their seat at the table” while also “sending and receiving gifts, including poker chips”. An example of items players can purchase from the virtual gift shop are entertainment tokens and international flags that, once purchased, accompany your avatar (either temporarily or permanently).

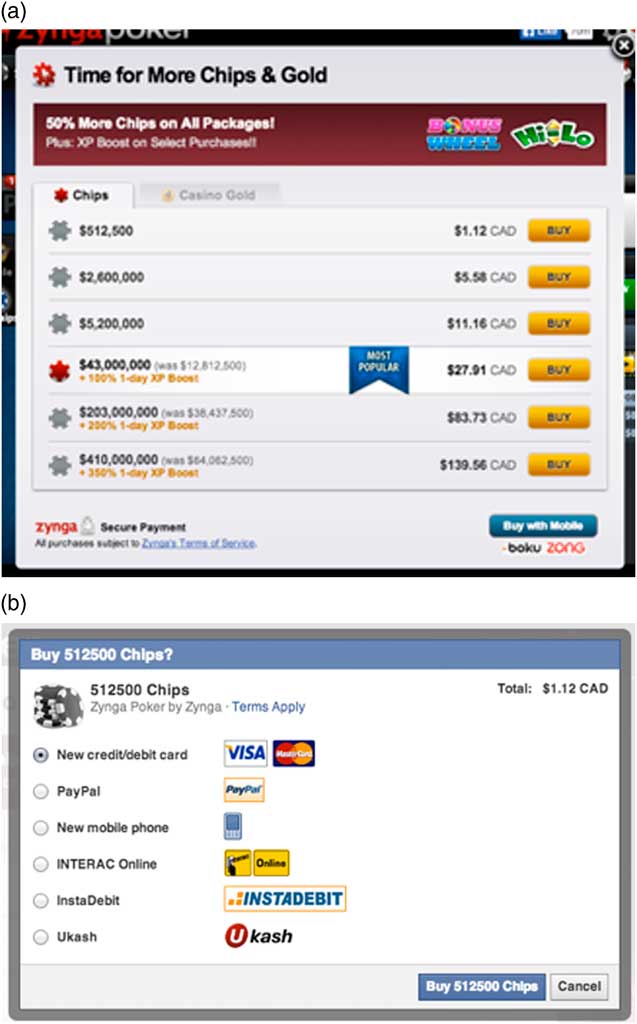

There are two types of currency in ZP: chips and casino gold. Chips are used for basic game playing and can be used across Zynga games. There are several ways a player can receive more chips: referring friends to play, logging in on a daily basis, winning hands, sending chips to/from online buddies, and purchasing. Casino gold, on the other hand, is ZP’s in-game currency and can only be purchased once players have depleted their complementary 8 pieces received upon registering to play. As shown in Figure 5, chips can purchase the majority of gifts; however, the permanent gifts can only be purchased with casino gold.

Figure 5 ZP purchasing virtual chips (images captured from the author’s computer on 10 May 2013)

One component of the virtual consumerism discourse is the ease of access for players to purchase additional chips or casino gold when required. As the screen shot in Figure 5 illustrates, there are a number of design features that allow players to instantly click to purchase additional chips through various payment options. For example, at the top of the screen, players can easily click on the link “Get Chips & Gold!” and instantly a pop-up window appears that allows players to select a number of different package options for both chips and casino gold, paying conveniently with a variety of payment options.

Further, if players find themselves having a run of bad luck over a series of hands, ZP automatically shows a pop-up window, which informs players how much they have lost, alongside the option to immediately purchase additional chips to get back in the game and, essentially, chase their losses (see Figure 6). It should be noted, that within the gambling field, the term chasing, refers to when players try to win back the money that they have lost and has been cited as one of the observable behaviours of individuals who may be gambling at problem levels.Footnote 44 By actively encouraging chasing, not only is ZP prompting players to virtually consume, they are also further reinforcing the harmlessness of this activity by understating the true nature of this particular behaviour.

Figure 6 Instant pop-up window to purchase additional chips (image captured from the author’s computer on 10 May 2013)

Finally, similar to any consumer purchase, purchasing chips or casino gold on ZP is subject to their Terms of Service. There is an interesting contrast between the wording of the Terms of Service document and the previous discourses of social connections, empowerment, and harmlessness, as constructed by ZP.

The discrepancy seems to be managed by obscuring the Terms of Services as a tiny link on the bottom of the payment options pop-up window (see Figure 5) or on the bottom of the poker room screens, centering significant attention on the ease with which virtual currency can be purchased, but hiding the legal framework that surrounds the purchase. According to the Terms of Service, players “have no right or title in or to any such goods or virtual currency appearing or originating in the Service”, and “Zynga has the absolute right to manage, regulate, control modify, and/or eliminate such virtual currency and/or virtual goods as it sees fit in its sole discretion”. Players who violate the Terms of Service are subject to being banned from all Zynga games, in addition to opening themselves up to potential legal repercussions. Essentially, Zynga is using the seductive power of poker to allure players into purchasing chips, while at the same time trying to ensure that in-game virtual currency, holds no value outside of ZP, by safeguarding itself from players who may wish to “buy or sell any Virtual Currency or Virtual Good for ‘real world’ money or otherwise exchange items for value” (Zynga, Terms of Service document). In essence, it is securing its non-adherence to the legal coordinates of gambling: consideration, chance, and prize.Footnote 45

4 Discussion

With respect to gambling, ZP depicts the latest installment of the continuing transformation of poker – a game that has been played for centuries. The game of poker may have had its genesis in players’ basements and dingy backrooms; however, thanks to the internet, expanded media attention, and now SNSs, the game has an unprecedented visibility that is attracting a new audience while challenging our understanding of what it means to gamble. Further, I would argue that as a result of social casino games’ underlying platforms (ie SNSs, mobile apps) and their use of player metrics, new risk and ethical considerations for risk regulation arise, specifically with respect to young players. As illustrated, game developers are personalising and tailoring the gambling experience to project a discourse that gambling is a harmless form of entertainment.

How individuals interpret risks is highly contingent on the socio-cultural context.Footnote 46 ZP’s deliberately designed “harmless” frame minimises players’ perception of associated risks and potential harms. It also demonstrates that the social processes behind shaping what is deemed “risky”, is not a neutral one, but rather always carries with it questions of power.Footnote 47 To date, dialogues regarding social casino games have been significantly driven by industry and related key stakeholders, who have set the terms and boundaries for how a discussion is carried out. As it currently stands, social casino operators, such as ZP, will be significantly impacted if we begin to define these activities as gambling under the traditional legal definition, specifically if winning a prize, other than money, holds value. Or if it is determined that social casino games have potential harms, particularly for adolescents who are not yet legally able to gamble in regulated online sites or land-based casinos. To maintain the level of freedom the industry currently has in this unregulated market, ZP has to continue to construct these games as just another form of free-to-play entertainment and maintain the harmlessness discourse that was active in the analysis of ZP.

While the purpose of my study was not to directly investigate the role that big data plays in social casino games, it is evident that it also cannot be overlooked in the discussion of the games and the influence that developers’ use of big data analytics has on youth gameplay behaviours. Zynga is a metrics-driven company,Footnote 48 capturing structured data on everything that happens within their games. Every single game is tracked, computing around 30–50 billion rows of data a day.Footnote 49 This data allows developers to use analytics to pull players’ online behaviour data (both inside and outside the game) to personalise (and actively alter) players’ gameplay to help optimise player retention and monetisation, a process referred to as predictive personalisation.Footnote 50

I would argue that Zynga’s use of big data analytics is an excellent example of dataveillance. Most concerning is how ZP is using knowledge derived from players’ gameplay and online practices to influence their actions intentionally to achieve business objectives – a form of behavioural manipulation to gain revenues. When it comes to young players, many may not recognise they are being “recorded,” “targeted,” and “nudged” by these manipulative technologies.

Risk has always been an inherent component of gambling. Players’ assume the risks voluntarily when they place a wager in the hopes of gaining some reward. However, as gambling opportunities continue to expand, innovate, and become a normalised cultural venture, governments and regulatory bodies worldwide have established gambling acts and codes of practice to raise awareness of hazards and risks associated with gambling within the regulated market, with some governments going so far as to implementing safeguards to prevent minors from being exploited and harmed by gambling. For example, the British legal framework specifically states that safeguards are designed to prevent children from being exploited or harmed by gambling.Footnote 51 As CarranFootnote 52 points out, despite measures to protect minors, the current British legal framework suffers from many statutory loopholes. One example is demo and practice sites offered by online casinos. “For all intended purposes they are virtual equivalents of land-based betting and gaming venues, but the Act does not provide any provision that would outlaw such virtual entry to minors”.Footnote 53

Social casino games are designed to replicate real-money gambling games and are the latest example of how rapidly-evolving technologies are blurring the lines between gambling and gaming. Game designers commonly use gambling elements, such as the mechanics of randomness (eg loot boxes, dice, or the dealing of cards), to make the game more uncertain for players, while social casino games are using social mechanics found in online games, such as leaderboards, chat features, and the players’ social connections via Facebook, to capitalise on the emerging unregulated gaming platform that Facebook has become. The implications of this research significantly contribute to youth gambling and gaming awareness and prevention initiatives by expanding programs to be more inclusive, in addition to understanding the environmental context that these games are built upon.

Public health scholars acknowledge “society’s representation of gambling can have a profound impact on youth”.Footnote 54 Game developers will always need to think about how they will drive players to spend money in the game. This can be a dangerous seduction for game developers focusing on maximising profits by customising the gameplay experience. While there is an obvious entertainment factor inherent in many social casino games, unregulated games like ZP present new challenges, which need to be considered, to protecting young people from harm.

From a public health perspective, key priorities should be to: (a) promote informed and balanced attitudes and behaviours towards social casino gaming; and (b) prevent and protect youth from social casino gaming harms. Health promotion, harm reduction, and primary prevention are examples of public health strategies used in interventions designed to support youth with issues related to gambling.Footnote 55

The term “health promotion” is generally used to describe “processes that enable youth to make informed choices about gambling and that foster their overall well-being by building on their assets and the capacities of family, peers, and community”.Footnote 56 As a response to the previous individualist and victim-blaming approach to health education,Footnote 57 health promotion seeks to move beyond the individual behaviour to explore its context, as well as the social and economic characteristics. Key interventions of risk perception have been shown to allow young people the opportunities to explore the concept of risk and their perceptions about risks related to gambling.Footnote 58

The word “risk” is often associated with danger.Footnote 59 However, I would argue that we need to move towards understanding risk, instead of fearing risk. The current knowledge promotes the dualism between social casino games and gambling; however, gambling and gaming should not be viewed as mutually exclusive, but rather intertwined activities sharing similar elements. This allows for a complete representation of the fluidity and transitory nature of youths’ gameplay that can range from healthy to problematic, while also examing the benefits and unintended negative consequences.Footnote 60

As expressed at the beginning of the article, Mark Pincus stated publicly that Zynga did anything possible to get revenues, to grow the business. As a publicly traded company on NASDAQ, it is safe to assume that a critical business objective is to maximise shareholder value by generating as much profit as possible. Being free to operate in an unregulated market with the purpose of generating revenue, findings from this case support how ZP used dataveillance to achieve this goal. Moving forward, several ethical questions need to be addressed, particularly when it comes to youth and underage players. What are the implications for young gamblers who are being personally encouraged to immerse themselves in their social casino gameplay as a result of advanced metrics and personalisation technologies? How can risk communication about social casino games be incorporated into current gambling and gaming health promotion initiatives? How can future research begin to understand the role of big data within F2P social games and the possible unintended negative consequences of targeting player behaviour for profit maximisation?

5 Conclusion

Through social casino games, young people are being exposed to gambling opportunities many years before being legally able to gamble. This exposure has significant implications for the protection and prevention of gambling-related harms to vulnerable populations, such as youth. Within this study, I sought to interact with ZP to examine: (1) What are the discourses embedded in Facebook’s popular ZP application? And (2) How do the game’s social and design elements shape youths’ experiences of poker on Facebook? This case illustrates how visual images and texts powerfully work together to render a discourse.Footnote 61 Discourses, such as social connection, harmlessness, empowerment, and virtual consumerism, were found to actively play out according to the design of ZP. Further, after personally putting myself into the game by playing poker and engaging with the discourses and intentions of the game design, I argue that Zynga has designed ZP to be a thoroughly engaging journey for players, catering to both their emotional and their skill-driven needs. In essence, Zynga has actively developed a habit-forming product, linking their game into the daily routines and emotions of many players.