Historic events through 2020 prompted healthcare professionals in popular media, conferences, and academic journals to reflect on how social structures shape population health and medicine.Footnote 1 , Footnote 2 The global coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic not only underscored stark hierarchies of inequity in societies,Footnote 3 , Footnote 4 but also demonstrated the urgent need for healthcare systems to better prepare for the unfolding climate change crisis, which will similarly have disproportionate impacts on marginalized communities and the Global South.Footnote 5 Additionally, the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, with its unprecedented global reach, illuminated how institutional practices emerge from and can reinforce harmful social structures.Footnote 6 , Footnote 7 We have witnessed our colleagues in healthcare grapple with this reignited, and at times newfound, consciousness of the ubiquitous social forces that operate within the lives of patients, our healthcare institutions, and broader society. This includes calls for bioethics to take stances on global humanitarian crises, such as the war in Ukraine.Footnote 8 Unfortunately, in everyday practice though, health professionals can feel powerless against social structures, which exacerbate the very problems that they are committed to addressing. As healthcare ethics consultants, we too have reflected on how fostering a more ethical healthcare system necessitates a sociological lens, including considering our own relationships with social structures of inequity. In the words of medical sociologist Renée Fox, an inward sociological reflection can aid in moving our profession “toward its better self.”Footnote 9

Bioethics scholars have long called for an intersectional and critical framework that resists structures of inequity in society.Footnote 10 , Footnote 11 Yet, incorporating a sociological lens into healthcare ethics presents many challenges. Historically, bioethics has prioritized analyzing ethical elements within the dyad of the doctor–patient relationship. Healthcare ethics consultation services are emergent from this disciplinary focus. In our work, we center on factors that immediately impede decision-making to provide guidance on the complex moral problems confronted in daily practice. Through an ecological lens, this may include factors at the individual or meso-levels. Meanwhile, the field of bioethics has increasingly drawn from a broader array of perspectives across the humanities and social sciences to enrich our understanding of the relationship between bioethical problems and social, political, and economic systems.Footnote 12 Although these academic efforts have advanced our conceptual knowledge of healthcare ethics, it is less obvious whether and how healthcare ethics consultants can broaden their gaze and practically incorporate a sociological analysis in their day-to-day work within healthcare settings. As societies contend with dramatic challenges to democracy and their social fabrics, with downstream consequences for rights in the clinic, we view this challenge as an invitation for bioethics to critically reflect on our relationship with social, political, and economic systems.

To this end, in this article we respond to this conceptual gap in healthcare ethics by proposing a sociologically informed ethical inquiry termed social bioethics. We define social bioethics as an approach to healthcare ethics analysis that demonstrates how broader social structures contribute to ethical problems within healthcare, an analysis that is accomplished through the social scientific framework of interpretivism. In particular, interpretivism aids in identifying operating sociological discourses in everyday problems confronted in the clinic.

We argue that social bioethics can be a useful tool for healthcare ethics consultants to aid healthcare institutions and professionals to understand how their actions both impact patients and shape social structures. To demonstrate our arguments, we first discuss the relationship between medicine, social systems, and ethical problems in healthcare. Second, we discuss interpretivism as our proposed methodological approach. This includes resolving conceptual debates on the compatibility of interpretive social sciences and normative theory. Lastly, we conclude with recommendations for future scholarship on social bioethics and healthcare ethics.

Social Scientific Perspectives of Medicine

An organizing principle for social bioethics is that medicine is a social institution. Broadly defined, social institutions are organizations that emerge within society, organize human activity, and consist of social practices to meet specific needs or fulfill specific functions. Prominent examples of social institutions include education, religion, the economy, and the nuclear family.Footnote 13 Medicine is formalized as physical institutions in society through hospitals, outpatient clinics, and nursing facilities, of course. However, as a social institution, we specifically aim to highlight that medicine plays a ubiquitous role beyond its physical establishments. Medicine is a central lens through which societies think about and address their fundamental problems. This includes the fact that medicine has a range of governing roles in society, such as regulating individual behavior (e.g., involuntary psychiatric commitment), healthcare product regulations, and population health guidelines. As medical sociologists highlight, medicine has also played a historic role in the framing of social identities including race, sex and gender, disability, and sexuality.Footnote 14

There are many frameworks in the social sciences to characterize the relationship between medicine and society. In recent years, the social determinants of health framework has gained increased attention, wherein social structures are thought of as active forces that shape, facilitate, and infringe upon individual health.Footnote 15 Although we believe this framework has an important place in bioethics, we caution that it risks prompting individuals to conceptualize social factors as elements that “surround” the clinical interaction, rather than as constitutive components in the interactions between healthcare systems, treatment teams, and their patients.Footnote 16 For social bioethics, a social determinant model is problematic for two reasons. First, if social factors are conceptualized as existing only outside of healthcare institutions, then there is no conceptual basis for healthcare professionals to name and address said social systems within the design and delivery of care itself. (Indeed, we argue that this itself can lead to feelings of powerlessness against said social systems.) Following this, there would also be no basis for healthcare professionals to critically interrogate how healthcare policies, medical interventions, and treatment decision-making are emergent phenomena from said social structures. This includes, of course, critically examining the relationship between social structures and the contributions of healthcare ethics consultants.

An emerging framework that social bioethics builds on is structural competency. Footnote 17 Helena Hansen and Jonathan Metzl introduced this framework by arguing that the pedagogical framework of cultural competency does not sufficiently consider how stigma and inequity are rooted at structural levels. Instead, physicians should be trained to understand “how social and economic determinants, biases, inequities, and blind spots shape health and illness long before doctors or patients enter examination rooms” (p. 127). We too aim to highlight the role of structures in shaping medicine; however, instead of identifying its implications for health outcomes per se, social bioethics centers on how ethical problems are emergent from social conditions and their implications for the design and delivery of healthcare.

Medical Discourse and Power

In characterizing medicine as a social institution, we draw from Michel Foucault’s concept of discourse. In his work, Foucault was concerned with understanding how societies come to govern the bodies of individuals through the discipline of medicine, a phenomenon he termed biopower. Footnote 18 Foucault articulated that biopower is accomplished through the production of discourse, which is a shared set of assumptions regarding the nature of individuals and social problems. These assumptions organize social relations and become the basis on which operating logic is derived to guide conduct. It is through this lens that Foucault explored the construction of mental illness, sexuality, and doctor–patient relations post-modernity.Footnote 19 , Footnote 20 , Footnote 21 Since then, contemporary scholars have used Foucault’s concepts to illuminate how discourses in health policies, scientific research, and medical technologies, and, as it pertains to our interests, medical moral reasoning are derived from the interests of groups in power.Footnote 22

There are many ways to illustrate our point. Consider the historic social forces that have shaped the policies, procedures, and social acceptance of involuntary psychiatric commitment in the United States. In the mid-1800s, advocates such as Dorothea Dix catalyzed public awareness of the deplorable living conditions of people with psychiatric disabilities, many of whom were left in prisons.Footnote 23 Drawing from English models of social welfare, a new sense of both public responsibility and stigma-based interests to keep mental illness hidden gave rise to the psychiatric institution. Admissions continued to rise through the 1950s until states no longer could foot the bill.Footnote 24 Additionally, public consciousness grew concerning the extreme physical and psychological abuse that occurred behind closed doors, which was paired with a diverse set of countermovements spearheaded by thinkers such as Thomas Szasz, R.D. Laing, and Franco Basaglia.Footnote 25 A new vision for community-based treatment emerged, promoted by both activists and the federal government,Footnote 26 and was paired with a newfound vision for psychiatric drugs to foster independent citizens and discontinue ongoing use of welfare services.Footnote 27 Thus began deinstitutionalization, a process by which tens of thousands of hospitalized patients were emptied back out into their unprepared communities in hopes that they would be transformed into “everyday citizens.”Footnote 28

Unfortunately, in the following decades, the United States federal government failed to deliver on its promise of a robust financing infrastructure. Conversely, with the advent of neoliberal economics, federal administrations prompted drastic budget cuts to mental health services, as well as welfare programs more broadly. In this context, with insufficient services to support people through their disability, the mental health movement has emphasized the importance of recovery from mental illness.Footnote 29 Still, today, people with psychiatric disabilities experience disproportionate rates of violence victimization, homelessness, emergency service utilization, and mass incarceration.Footnote 30 , Footnote 31 Like in the era of Dorothea Dix, these social conditions have sparked a renewed interest in involuntary treatment in the public consciousness, particularly as politicians make promises to their constituents to address their apparent concerns about homelessness and community violence.Footnote 32

To be clear, we are not necessarily arguing whether involuntary commitment itself is ethical or even effective at achieving its aims at various points. Rather, we aim to highlight how medicine plays a central role in understanding how to respond to psychiatric disability, and what is understood as an appropriate response is shaped by broader social, economic, and political forces. Here, various social discourses shape how medicine, as a social institution, responded. These discourses include the construction of people with psychiatric disabilities, concerns about their vulnerability and dangerousness in community contexts, and welfare economics concerning what types of services the government should and should not fund. Furthermore, our aim is not to explore each of these individual discourses in this article. Rather, we aim to demonstrate that medicine’s role in society is not “naturally derived” from its capacities, but is grafted onto medicine itself by social actors with specific culturally situated interests.Footnote 33

Discourse guides not only federal and state policy; it also forms the conceptual basis on which individuals interpret their realities in treatment decision-making and care.Footnote 34 Discursive logic can be both explicitly and implicitly communicated by individuals and embodied in daily decisions, which disseminates and reifies its presence. The most prominent example of this in healthcare settings is referred to as medical discourse, which is a set of biomedical assumptions concerning how to examine, diagnose, and treat symptoms and diseases.

In returning to our previous example of psychiatric care, federal, state, and hospital policies establish their policies regarding involuntary commitment, which has downstream effects on treatment providers in the clinic. In particular, involuntary commitment policies and procedures must be interpreted and enacted by treatment teams in daily decision-making with patients and their families. At times, these discourses may take on a life of their own beyond the intentions of policymakers, or even be packaged into sayings that can be disseminated (such as evoking the line “danger to self or others”). To note, medical discourses—even if reduced to basic principles for individuals to follow—are complex: They have their own histories, imply different types of analyses for various individuals, and, importantly, may provoke individuals to position themselves against specific framings. In returning to our example, this includes the important role of countermovements in psychiatry and mental health services, which have explicitly positioned themselves against coercion or medicalization.Footnote 35 In other words, social discourses do not determine the outcomes of analysis, per se, but they do set a framework for individuals to socially operate within.

Moral Discourse

As it pertains to social bioethics, medicine participates in constructing standards for ethically acceptable care. Most evidently, healthcare professionals opine, both in academic journals and to the public, on their moral reasoning for allowing or restricting specific practices. Ethical norms are also identified in formal bioethics scholarship, reflecting the culture that scholars and clinicians are situated within. Similar to medical discourse, ethical norms are taken up, interpreted, and modified in the everyday moral reasoning of healthcare professionals.Footnote 36 In the social sciences, this type of reasoning is referred to as a moral discourse. Indeed, healthcare ethics consultants can be thought of as interpreters of this: We intentionally engage in the operating moral discourses within clinical spaces and reveal the working assumptions about the problem at hand.

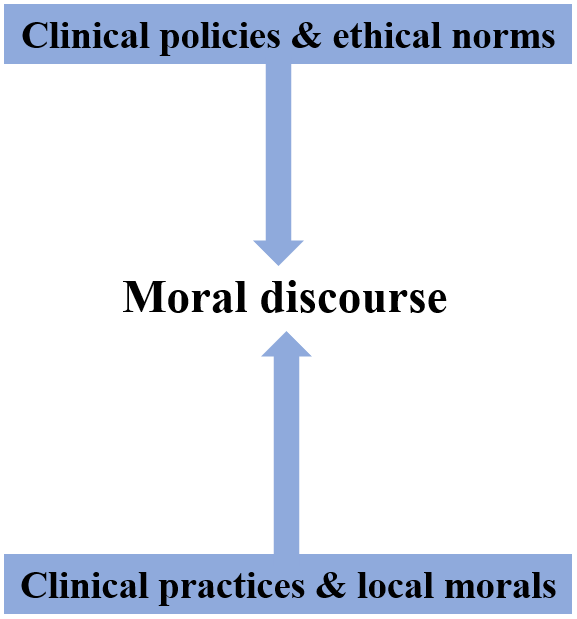

How moral discourse is derived can be thought of as emerging from a complex set of discursive elements across social–ecological levels.Footnote 37 , Footnote 38 Consider Figure 1 that depicts this.

Figure 1 Social–ecological structure of moral discourse.

On the macro-sociological level, we might consider how moral reasoning is partially born from the cultural beliefs and values that underlie our society.Footnote 39 From a more critical lens, we might also consider how the ends of a form of moral reasoning are aligned with a society’s own aims to reproduce power structures.Footnote 40 On a meso-sociological level, we can consider how moral reasoning is shaped by local elements. For individuals in the clinical space, for example, their moral reasoning may stem from their interpretations of state and hospital policies on specific issues. Similarly, the availability of local medical and welfare resources for vulnerable patients might set the stage for ethical issues about safe discharge plans, including both access to housing and the ability to seek follow-up care in an outpatient setting. Lastly, on a micro-sociological level, individual experiences with medical, welfare, and interpersonal elements may shape how individuals synthesize moral reasoning. By highlighting the role of these elements in moral reasoning, we argue that social bioethics can empower individuals to acknowledge the social forces that they are up against and consider how their actions implicate them. And by noting these factors, social bioethics can allow for pragmatic inquiry to resolve emergent ethical problems.Footnote 41

The right column in Figure 1 depicts discursive elements, at various social–ecological levels, which could influence how a treatment team and patient consider the ethical permissibility of involuntary commitment treatment. Drawing from these discursive elements, a treatment team might consider what is and is not permissible in the context of their concerns for a patient’s vulnerability: to either violence in the community or coercion in healthcare settings. A patient’s own lived-experience with mental health services, and relationship with healthcare institutions, may deeply inform their moral reasoning too. In this case, a patient may be acutely aware of the risks of community living,Footnote 42 but view these as less burdensome compared with the harms of losing personal autonomy in a confined treatment setting. We also cannot ignore the prevalent role of sanism in healthcare and whether or not the knowledge of people with psychiatric disabilities is acknowledged and appreciated, particularly in treatment decision-making.Footnote 43 Perhaps both treatment teams and patients are struck by the limited types of services available that could be more value concordant for the patient. In the particular historical context we live in, this includes navigating disability with limited welfare and mental health services.

Here, we do not present a social–ecological model to be prescriptive or set limits on how one thinks about the influence of social elements in moral reasoning. We present it as one potential tool that social bioethics might draw from to engage in broader sociological thinking. Furthermore, we do not necessarily seek to make claims regarding whence a moral discourse “originates.” Instead, borrowing from the anthropological work of Paul Brodwin, we think of moral discourses as coproduced across social–ecological levels.Footnote 44 As we have explored, elements on the macro-ecological level set the stage for how individuals frame problems; individuals themselves may take up, reify, or even subvert the influence of these discourses. In doing so, they contribute to the ongoing revision of broader social moral norms in a society in a cyclic relationship. We have depicted this type of relationship in Figure 2. Lastly, our diagram does not necessarily depict how moral discourse is situated alongside other social forces regarding the phenomena at hand or is co-constructed alongside other discourses that involve systems of race and gender, which we believe can be central to understanding moral reasoning in healthcare.Footnote 45

Figure 2 Coproduction of moral discourse based on Paul Brodwin (2008).

Although sociological reflection is vital, the social world is complicated: It emerges from an unfolding historicity, stormy with political events, and alive with ubiquitous social structures that perpetuate stark hierarchies. Social structures are often concealed, unknown to the actors who uphold them, and can be ambiguous, even if their presence in healthcare is delineated in theory and research. How are we to untangle this social reality? Second, healthcare ethics consultants not only need to engage in a form of social scientific inquiry but must also be equipped with the proper tools to reflect on their own positionality that shapes their inquiries. How do we arrive at the same understanding of bioethical problems, given our complicated relationships with the social world we too are constituted from? How might we think about the relationship between the social positionality of ethicists and their interpretations of social dynamics in ethical problems? Or how do social systems shape the ways patients experience problems and how treatment teams frame ethical issues? These questions point to the need for a sociology of knowledge production that draws pragmatic implications for our own analyses and recommendations. For this, we turn to the interpretive social sciences.

Interpretivism: Past an Epistemological Divide

Interpretivism is an approach to social scientific inquiry that considers truth to be a product of meaning-making processes between epistemic actors, who themselves are nested within broader sociological levels of truth production and contestation.Footnote 46 It is a broad categorical approach within the social sciences, ripe with internal debates about the nature of reality, knowledge production, and axiology. What unites interpretivism, however, is its critique of positivism (earning the title of antipositivism) on the basis that social phenomena cannot be reduced to mechanistic causations, which is argued to strip subjects of their historic and political contexts.Footnote 47 Instead, interpretivism focuses on constructed meaning, including its relationship with broader social systems, and considers this to be the foundation upon which actions emerge and are made legible by others. Through emphasizing meaning-making, researchers develop new insights into how social elements constitute phenomena, often in ways that are not immediately obvious to individuals at the moment. As stated in Interpretive Social Science: A Second Look by Paul Rabinow and William Sullivan:

To understand an author better than he could understand himself is to display the power of disclosure implied in his discourse beyond the limited horizon of his own existential situation. Social structures, cultural objects, can be read also as attempts to cope with existential perplexities, human predicaments, and deep-rooted conflict. In this sense, these structures too have a referential dimension. They point toward the aporias of social existence.Footnote 48

Qualitative research methods are often the primary tools used to analyze the discursive realities that people are engaged in, which encompass ethnography, constructivist grounded theory,Footnote 49 and situational analysis.Footnote 50 These methods emphasize detailing the subjective accounts of actors, illuminating operating and shared assumptions, and analyzing how meaning is co-constructed between actors. This can be accomplished through direct observations of social phenomena, including embedding oneself in cultural or institutional settings to detail day-to-day interactions and in-depth interviewing.Footnote 51

How would interpretivism aid in social bioethics? Broadly, by pairing our ethical commitments with social facts, we can more effectively realize what our ethics ask of us in navigating our social world. To do this, interpretivism can guide healthcare ethics analysis to identify the presence of social factors via its discursive role in framing clinical decision-making and policymaking. Social scientists who use interpretivism have developed various methodological tools that healthcare ethics analysis can draw from to identify, articulate, and account for these social elements. For example, Adele Clarke’s situational analysis allows researchers to identify social structures—including cultural institutions, social policies, and discourses—not merely as factors that “surround” a situation but as co-constituents in the emergence of how we interpret and navigate problems.Footnote 52 In one of her proposed approaches, for example, researchers map out the intersecting set of social, cultural, and institutional systems that are present in a clinical phenomenon. Then, researchers consider the role of these in how research subjects frame and analyze the problems they are navigating. Through using interpretivism in this sense, social bioethics can frame social elements as more than contextual factors, too, and instead focus on how social elements give rise to ethical problems in medicine.

Although interpretivism is concerned with highlighting the presence of broader sociological elements, it also understands how these elements synthesize across ecological levels to constitute the individual experience. In this sense, social bioethics does not abstract away from the micro-sociological level; instead, it enriches our understanding of individuals, both patients and treatment teams, in navigating ethical issues. To note, healthcare ethics consultants may engage at these levels of discourse production at each social–ecological level. Healthcare ethics consultants may be involved in developing regional, local, or institutional policies or, in the case of clinical ethics consultation services, in examining and interpreting the moral reasoning operating within treatment decision-making processes.

By drawing a link between sociological levels via interpretivism, social bioethics can serve as a type of interpreter that makes sense of how moral discourses develop and shape healthcare. For example, a consultant might advise policymakers on how ethical rationales may “trickle down” to shape the behaviors of clinicians. Similarly, they might highlight how certain social dynamics present in the clinic, but unknown to policymakers, undermines or bolsters ethical care. Conversely, on the frontline, social bioethics may aid clinical ethics consultants in interpreting the reasoning of certain policies for clinicians, including highlighting the social, political, and economic stakes that may have shaped its development. This may lead to a deeper appreciation of the intention of certain policies and allow for greater fidelity to key ethical norms.

Responding to Critiques of Interpretivism

We are not the first to suggest the incorporation of social scientific methods to bolster bioethical inquiry. Yet, scholars have raised several critiques regarding incorporating social scientific methods into bioethics, which we will respond to here. One major critique is that interpretivism is incompatible with normative theory. This argument posits that interpretivism assumes that ethical principles are wholly socially constructed. Following this logic, distilling normative commitments would be an impossible task as principles are bound by time and place, doomed to be outdated by changes in the social world.

We assert that this is a mischaracterization of interpretivism. Interpretivism itself neither ontologically denies a shared reality between social actors nor pursues an infinite regress of deconstructing truth claims.Footnote 53 Instead, interpretivism begins and ends with the assumption of a shared reality that engages the subjective to identify structures that permeate our lived experiences. In this regard, interpretivism can be compatible with normative bioethics and enrich the field with frameworks to explore the complexity of moral experience. Like others before us, we argue that the interpretivism does more than merely deconstruct problemsFootnote 54: it aids in the construction of new understandings of ethical problems, which may guide healthcare ethics consultants in fostering ethically supportable treatment and care and in this way construct or anticipate new normative frameworks. In other words, interpretivism is about meaning-making.

The second set of critiques concerns the particular aims of interpretivism versus normative theory. Some social scientists have argued that bioethics avoids the social particularities of a given situation to distill transferable logic and formulate solutions, and thus misses out on “thick description.”Footnote 55 Such a critique characterizes the field as a set of parables, relying on archetypes and reductive characters or conflicts to extract a metaphorical “moral of the story.” This generalization is what we refer to as the parable problem of bioethics. Conversely, some ethicists may be wary of the social sciences, as its methodologies often lean into the complexity of situations to describe the possible infinite factors that shape our social worlds and structures of signification. This, in itself, does not lend to creating solutions to pressing moral problems, especially ones that can be elegantly taught and implemented in the clinic. As Daniel Callahan once asked: “How do we make good of the knowledge produced in the social sciences?”Footnote 56 In other words: What is the most beneficial type of knowledge to foster ethical decision-making in medicine, and what are the unique contributions of the interpretive tradition?

We acknowledge that these arguments demonstrate potential issues with incorporating interpretivism in healthcare ethics but argue that these concerns alone should not rule out its use altogether. First and foremost, although bioethicists are concerned with principles or logic that operates within medicine, these issues operate within the real world, which itself is empirically describable.Footnote 57 As Leigh Turner argues, sociological critiques of bioethics are apt to miss this point: “Bioethicists are [not] indifferent toward the complex social worlds that social scientists explore” (p. 37).Footnote 58 Similarly, although we argue that healthcare ethics consultants aim to benefit from sociological methods, we acknowledge the serious concerns associated with pursuing rich descriptions. Not all facts are useful or necessary for distilling certain truths or guiding ethical conduct. Still, the aim of interpretivism is not mere description as an end in itself, but to formulate a coherent synthesis of operating social elements. In this sense, the addition of the interpretive framework is to make more explicit the tools used to make sense of our worlds.

Conclusions for Healthcare Ethics

To conclude, ethical issues emerge from and are framed by a complex web of social discursive elements. These discourses can be understood as operating at various social–ecological levels and converge to coproduce operating moral discourses. In this article, we have argued that understanding the role of these discourses in ethical issues in healthcare is an important step toward fostering a more ethically supportable system. To accomplish this, we propose the concept of social bioethics, a particular type of analysis aided by the interpretive social sciences, which aims to understand the relationship between ethical problems and the broader social structures in which they are situated. There are various aims that can be derived through this type of analysis. First, by conceptualizing ethical problems and social structures as existing in a cyclic and reciprocal relationship, social bioethics can foster critical reflection on how our moral reasoning steers medicine, as a social institution, through social structures. Similarly, another aim of social bioethics can be to work against the decontextualization of ethical problems in medicine, as it considers ethical problems to be an epicenter where evolving and contested medical, legal, and cultural discourses are rendered a site of contestation. Furthermore, it may encourage bioethicists to see ethical problems as epicenters where evolving and contested discourses are challenged, become unintelligible or unavailable given the circumstances, or no longer map onto the lived experiences of individuals. This may prompt the need for new ethical frameworks that provide more utility for navigating ethical issues in real time.

Lastly, we believe that broader ethical obligations can be derived from our framework. Indeed, bioethicists have wrestled with whether the professional community should take political stances on social issues. Although some have argued for the possibility and importance of taking neutral positions on social issues,Footnote 59 others have advocated for bioethicists to be socially conscious and politically active. In exploring the possibility of a social bioethics, we suggest that healthcare ethics professionals are inevitably engaged in the political life of medicine. That is, although the amplified attention to health inequities is encouraging, we must not shy away from the more difficult challenge, which is to engage in a reflexive praxis of examining how medicine (and our own work, as healthcare ethics professionals) operates in relation to the problem and not be a mere arbiter on the sidelines.

In this sense, we argue that healthcare ethics—often embodied in consultants who are socially embedded in healthcare settings—can be understood as mediators of moral discourse between individual actors. Here, we refer to the “convening power of bioethics” to bring multidisciplinary perspectives together.Footnote 60 In addition, by highlighting how moral discourse is also emergent from broader social discourses, healthcare ethics can also be understood as mediating the relationship between the moral discourse of medicine and society. Following this, the actions of healthcare ethics consultants can also be thought to contribute to existing moral discourses in medicine by actively reifying, modifying, or subverting what is a permissible role for medicine to play in society. In other words, our recommendations implicate ethical reasoning beyond the immediate encounters we might consult on. To this end, healthcare ethics consultants do not merely reframe problems for individuals on the ground: We are actively shaping the social structures that medicine is embedded within.

Thankfully, our concept of social bioethics is preceded by decades of research and scholarship across disciplines, including calls for black,Footnote 61 feminist,Footnote 62 queer,Footnote 63 and disabilityFootnote 64 bioethics. Such scholarship provides a robust basis for social bioethics to identify and analyze the social discourses in which we are embedded. We hope this call is received as an invitation for intersectional and coalitional work that turns its attention to the role medicine has and has yet to play in responding to social inequities in society. Indeed, we believe this can start in the everyday work of healthcare ethicists as they grapple with ethical problems in tandem with individuals and their communities.

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.