Use your power for good: plural valuation of nature – the Oaxaca statement

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 February 2020

Non-technical abstract

Decisions on the use of nature reflect the values and rights of individuals, communities and society at large. The values of nature are expressed through cultural norms, rules and legislation, and they can be elicited using a wide range of tools, including those of economics. None of the approaches to elicit peoples’ values are neutral. Unequal power relations influence valuation and decision-making and are at the core of most environmental conflicts. As actors in sustainability thinking, environmental scientists and practitioners are becoming more aware of their own posture, normative stance, responsibility and relative power in society. Based on a transdisciplinary workshop, our perspective paper provides a normative basis for this new community of scientists and practitioners engaged in the plural valuation of nature.

- Type

- Intelligence Briefing

- Information

- Creative Commons

- This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s) 2020

Footnotes

i The workshop was supported by the project ‘Nurturing a Shift towards Equitable Valuation of Nature in the Anthropocene’ (EQUIVAL) of the Future Earth-Pegasus programme, Future Earth Montreal Global Hub, the Capacity Building Programme Mentoring Program on Plural Valuation supported by Future Earth's Natural Assets Knowledge–Action Network, the Institute of Ecosystem and Sustainability Research at the Autonomous National University of Mexico, the Basque Centre for Climate Change, the Programme on Ecosystem Change and Society (PECS) and ecoSERVICES of Future Earth, SwedBio GIZ-BMUB, the ESP Working Group on Integrated Valuation and UNESCO.

References

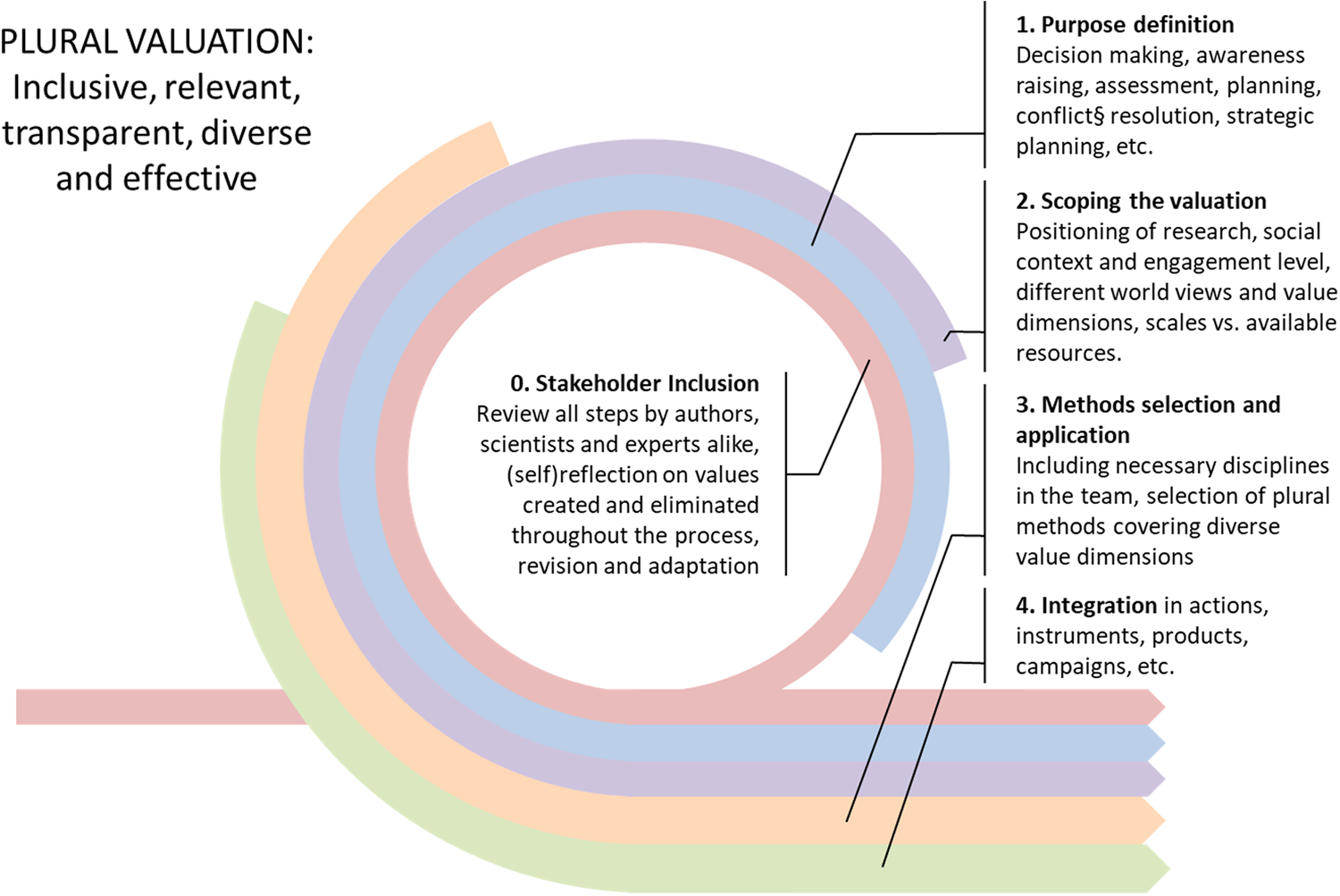

Fig. 1. Inclusiveness and different steps in the process of the plural valuation of nature. For more details, see, among others, Dendoncker et al. (2013), Díaz et al. (2015), Boeraeve et al. (2015), Kelemen et al. (2015), Gómez-Baggethun et al. (2016), Barton et al. (2016), Jacobs et al. (2016, 2018), Pascual et al. (2017) and Arias-Arévalo et al. (2018).

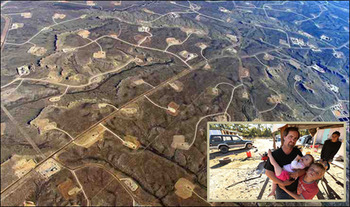

Fig. 2. The need for a more plural valuation. George Palmer with baby Ruby, son Peter, 7, and stepdaughter Karolina, 16, at their home in Tara, west of Toowoomba, Australia. George is worried that his family's health has been compromised by the massive expansion of the coal seam gas industry in the region (picture: Lyndon Mechielsen, https://www.theaustralian.com; aerial view: Simon Fraser University, Flickr). Fracking megaprojects exemplify the destructive pursuit of short-term economic profit for the few, at the cost of the local economy, quality of life and the diversity of values of nature for the many. The decision power of affected local communities is extremely low, resulting in protest, conflict and despair. Plural valuation could help visualize and address these conflicts and advance pluralistic decision-making (Phelan et al., 2016).

Fig. 3. octupy: oc⋅tu⋅py /ˈäktəˌpī/ verb. To access and transform various institutions in an active yet constructive manner, with the dual goal of participating in and connecting with a shared goal. Picture from British Library Open Flickr account. British Library HMNTS 10492.ee.20. BUTTERWORTH, Hezekiah, 1891.

- 71

- Cited by

Social media summary

Neutrality or power? Capturing plural values of nature needs a well-defined vision, a bold mission and clear strategies.

If you advance not knowledge, they will perpetuate ignorance;

If you exert it not for good, they will for evil.

– Frances Wright, Scottish writer1. Introduction

This paper summarizes the outcomes of a workshop on multiple values of nature held in November 2017 in the city of Oaxaca, Mexico.Footnote i The workshop convened 28 participants from diverse regional, disciplinary and professional backgrounds, active in transformative research and practice. After sharing local, sub-global and global experiences on the plural valuation of nature, we identified a common vision, a mission to pursue with the growing plural valuation community and part of a strategy going forward.

Nature is valued in very different ways by individuals and groups with very unequal levels of power, and a more plural approach to valuing nature is increasingly seen as critical to addressing deep inequities, injustices and conflicts. Scientists and practitioners working on the valuation of nature have a position of power to contribute to addressing this challenge. Yet the power of the research community to foster change remains unrealized as the dominant scientific postures and academic structures, as well as institutional incentives at a practical level, can often restrict open debate and constrain transformative change. Recent research on the ineffectiveness and potential harmfulness of single-approach valuation (e.g., Bigger et al., Reference Bigger and Robertson2017; McDermott et al., Reference McDermott, Mahanty and Schreckenberg2013; Pascual et al., Reference Pascual, Phelps, Garmendia, Brown, Corbera, Martin and Muradian2014; Poole, Reference Poole2018; Rozzi, Reference Rozzi2012; Turnhout et al., Reference Turnhout, Waterton, Neves and Buizer2013) has increased awareness of the importance of plural valuation. We argue that a global paradigm shift towards a more plural valuation is urgently needed, and in support of the emerging plural valuation initiatives we propose a shared vision, mission and strategy for the growing group of researchers and practitioners who (re)position themselves at the frontline of post-normal and action-orientated research, as well as decision-making around nature.

2. Valuing nature for sustainability?

Protecting life through the sustainable use of nature is at the heart of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs). The SDGs aim to reconcile ambitions for human resource use with ethical considerations and ecological limits. Globally, nature and its associated contributions to peoples’ quality of life are in severe decline (Chaplin-Kramer et al., Reference Chaplin-Kramer, Sharp, Weil, Bennett, Pascual, Arkema and Daily2019; IPBES, 2018a, 2018b, 2018c, 2018d, 2019; WWF, 2018). Valuation of nature – in its broad sense of assessing its importance and significance for people's quality of life – is essential to making societal decisions on nature's management and the use and distribution of its contributions. Values related to nature are articulated by diverse institutions and are as such associated with culture and traditions, which together impact nature through several mechanisms (Aragão et al., Reference Aragão, Jacobs and Cliquet2016; Hejnowicz et al., Reference Hejnowicz and Rudd2017; IPBES, 2015; Kelemen et al., Reference Kelemen, Barton, Jacobs, Martín-López, Saarikoski, Termansen and Turkelboom2015; Pascual et al., Reference Pascual, Balvanera, Díaz, Pataki, Roth, Stenseke and Maris2017; Šunde et al., Reference Šunde, Sinner, Tadaki, Stephenson, Glavovic, Awatere and Chan2018). In other words, none of these valuations are neutral, and more to the point, neither is the information underpinning them. Valuation is – often implicitly – based on specific lenses through which human–nature relations are perceived. Diverse views and aspirations, cultural norms, differences in power, gender, class, religion and age all influence the ways in which values are attributed to economy-related profit values, biodiversity and socio-cultural heritage (Arias-Arévalo et al., Reference Arias-Arévalo, Martín-López and Gómez-Baggethun2017; Klain et al., Reference Klain, Olmsted, Chan and Satterfield2017). Consequently, differences in how we relate to nature are at the core of socio-environmental conflicts and represent a hidden bottleneck for realizing the sustainable and equitable flow of the contributions of nature to people within and across generations.

Recognizing the full scope of values of nature requires respect for the principles and practical implementation of diverse complementary valuations approaches. Since the Rio Summit in 1992, valuation has become a high policy priority, at least discursively, although mostly unidimensional perspectives have been applied (i.e., with either an economic or an ecological value lens) (Fagerholm et al., Reference Fagerholm, Torralba, Burgess and Plieninger2016; Liquete et al., Reference Liquete, Piroddi, Drakou, Gurney, Katsanevakis, Charef and Egoh2013; Martín-López et al., Reference Martín-López, Leister, Cruz, Palomo, Grêt-Regamey, Harrison and Walz2019; Nieto-Romero et al., Reference Nieto-Romero, Oteros-Rozas, González and Martín-López2014). More recently, the long-recognized need for including plural values has gained traction in the scientific literature and within science-policy platforms, such as the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). IPBES applies a fully fledged plural valuation framework, which aims at bridging worldviews and values held by diverse societal actors, from financial enterprises to indigenous and local communities (IPBES, 2015; Pascual et al., Reference Pascual, Balvanera, Díaz, Pataki, Roth, Stenseke and Maris2017).

This paper puts forward a vision, mission and strategy for scientists, practitioners and policy-makers engaged with sustainability challenges by fostering the practice of plural valuation. Co-developed by a geographically, disciplinarily and professionally diverse group and building on numerous other individuals, groups, ideas, papers and practices, we aim at stimulating a much-needed shift in valuation and its consequent policies and practices.

3. What is plural valuation of nature?

Plural valuation has been defined as a science-policy process that assesses the multiple values attributed to nature by social actors (i.e., actors with a stake) and how this knowledge can guide decision-making (Rincon-Ruiz et al., Reference Rincón-Ruiz, Arias-Arevalo, Nuñez-Hernandez, Cotler, Caso, Meli and Waldron2019). The growing literature on plural, inclusive or integrated valuation provides a broad range of guidelines for the practical implementation of nature valuation studies (see Figure 1). In plural valuation, valuation is not understood as a single, independent and discrete step of a research or assessment process embedded in a policy cycle, but rather as a deeper and more continuous process: values are intentionally or unintentionally excluded and included from the first steps of description, problem definition and project scoping, all the way up to the communication of results (Figure 1). Plural valuation aims to address these implicit valuation aspects by articulating values through a context-specific process that takes into account different worldviews, dynamic social–ecological interactions, power relations and plural value elicitation itself (Arias-Arevalo et al., Reference Arias-Arévalo, Gómez-Baggethun, Martín-López and Pérez-Rincón2018). Valuation is the collective responsibility of all societal actors involved, including scientists, decision-makers and funders.

Fig. 1. Inclusiveness and different steps in the process of the plural valuation of nature. For more details, see, among others, Dendoncker et al. (Reference Dendoncker, Keune, Jacobs, Gómez-Baggethun, Jacobs, Dendoncker and Keune2013), Díaz et al. (Reference Díaz, Demissew, Carabias, Joly, Lonsdale, Ash and Zlatanova2015), Boeraeve et al. (Reference Boeraeve, Dendoncker, Jacobs, Gómez-Baggethun and Dufrêne2015), Kelemen et al. (Reference Kelemen, Barton, Jacobs, Martín-López, Saarikoski, Termansen and Turkelboom2015), Gómez-Baggethun et al. (Reference Gómez-Baggethun, Barton, Berry, Dunford, Harrison, Potschin, Haines-Young, Fish and Turner2016), Barton et al. (Reference Barton, Andersen, Bergland, Engebretsen, Moe, Orderud, Vogt and Niel2016), Jacobs et al. (Reference Jacobs, Dendoncker, Martín-López, Barton, Gómez-Baggethun, Boeraeve and Washbourn2016, Reference Jacobs, Martín-lópez, Barton, Dunford, Harrison, Kelemen and Smith2018), Pascual et al. (Reference Pascual, Balvanera, Díaz, Pataki, Roth, Stenseke and Maris2017) and Arias-Arévalo et al. (Reference Arias-Arévalo, Gómez-Baggethun, Martín-López and Pérez-Rincón2018).

Engaging with an inclusive team of a wide range of stakeholders from practitioners to scientists in an open-minded, adaptive and self-reflective posture is essential for plural valuation (step 0; Figure 1). Regardless of the type of challenge or the scale, defining a clear purpose with societal actors through negotiation is the foundation for plural valuation (step 1; Figure 1). If this purpose takes into account the stakes, interests, power, influence and dependency of different actors, it communicates a shared understanding of the valuation scope (step 2; Figure 1). The scope makes explicit both the position and mandate of people involved in the process and the available human and financial resources for the valuation. This scope also determines the multiple disciplines, approaches, methods and metrics needed to capture the diversity of values (step 3; Figure 1). The result, as well as the uncertainties, caveats and risks of valuation, are then integrated in an adequate format for the purpose of valuation (step 4). Values are recognized, elicited, measured or co-created throughout all of these steps.

Despite the large knowledge limitations and uneven coverage of different value dimensions and worldviews, the field of valuation of nature has started to close some gaps. New developments include the integration of indigenous and local knowledge systems and practices (Tengö et al., Reference Tengö, Brondizio, Elmqvist, Malmer and Spierenburg2014), the development of integrative frameworks (e.g., Hill et al., Reference Hill, Kwapong, Guiomar, Breslow, Buchori, Howlett, Tahi, Potts, Imperatriz-Fonseca and Ngo2016; Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Dendoncker, Martín-López, Barton, Gómez-Baggethun, Boeraeve and Washbourn2016) and the comparative study of methods’ capacities to capture plural values (Arias-Arévalo et al., Reference Arias-Arévalo, Gómez-Baggethun, Martín-López and Pérez-Rincón2018; Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Martín-lópez, Barton, Dunford, Harrison, Kelemen and Smith2018; Martín-Lopez et al., Reference Martín-López, Gómez-Baggethun, García-Llorente and Montes2014). Yet, sound methodological approaches are not sufficient on their own. The transformative aspect of performing plural valuation tends to clash with the traditional posture of science as a neutral and objective institution (Crouzat et al., Reference Crouzat, Arpin, Brunet, Colloff, Turkelboom and Lavorel2018; Pielke Jr, Reference Pielke2007; Temper et al., Reference Temper, McGarry and Weber2019). Scientists often struggle with the fact that their individual and shared values, worldviews and institutional positions strongly affect the outcomes of their valuation work. Valuation must, therefore, be supported by an explicitly articulated normative vision to effectively align various practices towards the common goal of sustainability and resolving valuation disputes.

In order to start addressing the issues above, our workshop had the explicit aim to set out a vision, mission and strategy to stimulate and provide guidance to plural valuation approaches. Our aim is to provide a starting point for discussion and reflection for the many researchers and practitioners who are struggling to connect their disciplinary expertise with personal engagement for transformative change on the ground. The authors of these article are very clear about what they want, and they see themselves – and their audience – as a growing critical mass of post-disciplinary scholars and practitioners with a common vision, unbound by discipline.

4. The vision: strong sustainability

On the basis of the advances of the last decade of valuation, the visions and goals formulated by various initiatives and their application in diverse contexts, we formulated the following vision for plural valuation:

We imagine a world in which the diversity of values – especially neglected values – and knowledge related to nature and its contributions to quality of life are included in policy, decision-making, governance and practice to achieve a more just and sustainable world. We envision a world in which the participation and representation of all people is realized and nature's contributions to people are distributed equitably within and across generations.

It is argued that the recognition of the multiple values of nature leads to more equitable and more widely accepted decisions (Diaz et al., Reference Diaz, Pascual, Stenseke, Martín-Lopez, Watson, Molnár and Shirayama2018; Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Dendoncker, Keune, Jacobs, Dendoncker and Keune2013, Reference Jacobs, Dendoncker, Martín-López, Barton, Gómez-Baggethun, Boeraeve and Washbourn2016; Pascual et al., Reference Pascual, Balvanera, Díaz, Pataki, Roth, Stenseke and Maris2017). Plural valuation can also be more (cost-)effective for three reasons (Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Martín-lópez, Barton, Dunford, Harrison, Kelemen and Smith2018). First, although seemingly complex, recognition and integration of multiple values into decision-making can be achieved by combining established processes and tools. Second, increasing effectiveness by combining methods does not necessarily require a higher cost (Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Martín-lópez, Barton, Dunford, Harrison, Kelemen and Smith2018). Third, in comparison, unidimensional or single-method valuation estimates are often less reliable, making their application riskier (Martín-López et al., Reference Martín-López, Gómez-Baggethun, García-Llorente and Montes2014).

Decisions are more effectively informed by a richer understanding of the diverse values of nature as this can help identify options that optimize societal benefits while contributing to sustainability. For instance, large-scale hydroelectric projects might provide large societal benefits from a national economic point of view, but simultaneously negatively impact on the livelihoods and social values of local inhabitants. Therefore, recognizing and including local social and ecological impacts for a wide range of stakeholders might avoid severe injustices and social conflicts (Albizua et al., Reference Albizua, Pascual and Corbera2019; Jerico-Daminello et al., Reference Jerico-Daminello, Edda, Burgues, Jacobs, Dendoncker, Barton and Gómez-Baggethun2015) (see example in Figure 2).

Fig. 2. The need for a more plural valuation. George Palmer with baby Ruby, son Peter, 7, and stepdaughter Karolina, 16, at their home in Tara, west of Toowoomba, Australia. George is worried that his family's health has been compromised by the massive expansion of the coal seam gas industry in the region (picture: Lyndon Mechielsen, https://www.theaustralian.com; aerial view: Simon Fraser University, Flickr). Fracking megaprojects exemplify the destructive pursuit of short-term economic profit for the few, at the cost of the local economy, quality of life and the diversity of values of nature for the many. The decision power of affected local communities is extremely low, resulting in protest, conflict and despair. Plural valuation could help visualize and address these conflicts and advance pluralistic decision-making (Phelan et al., Reference Phelan and Jacobs2016).

Addressing the diversity of values can also support the integration and achievement of policy priorities (e.g., the UN SDGs and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets) and can inform policy tools such as natural capital accounting (e.g., System of Environmental–Economic Accounting (SEEA)) and intergovernmental environmental assessments (e.g., IPBES, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)). However, a prerequisite for integration is the existence of a context in which the values and goals of different actors can be freely voiced, articulated, understood, negotiated and incorporated into policies. Scientists can make a significant contribution to the creation of this safe space.

5. The mission: to transform

Realizing this vision requires transforming the way in which values of nature are currently recognized, represented, expressed and captured in dominant research and practice by:

• Fostering recognition of neglected voices and marginalized knowledge systems;

• Empowering and nurturing marginalized worldviews;

• Contesting and restoring power imbalances and injustices that result from current valuation processes;

• Revealing how values are embedded in individual and collective action, social norms and rules, as well as research methodologies and decision-making processes.

Committing to this mission requires substantially different practices and will impact what we choose as our funding sources, formulate project goals or research calls, solicit consultancy, communicate findings, produce research proposals and research outputs and, finally, contribute to our vision.

6. The strategy: to octupy

Plural (integrated, inclusive) valuation has been steadily gaining critical mass over the last decade, allowing researchers to develop skills and expertise, providing a scientific underpinning as well as testing applications in real-life practice and policy contexts. In order to work further on the above mission, it is key to contribute to the transformation of the institutions that – to a large extent – determine the ways in which nature is valued.

We created the word ‘octupy’ (Figure 3) to refer to the strategy we can employ, each in our own capacity, to realize transformation towards the integration of plural valuation in research and practice. However, it is essential to do this in an open, transparent and collaborative manner, without stepping in the way of each other or duplicating efforts. Etymologically, the term ‘octupy’ hybridizes the verb ‘occupy’, in reference to the strategy of collaborative and constructive occupation, and ‘octopus’, a metaphor for diverse yet connected initiatives: a remarkable feature of the Octopus genus is that the partly decentralized nervous system of the octopus operates its arms in a semi-autonomously yet coordinated manner for the common goal of the organism's development and ultimate survival.

Fig. 3. octupy: oc⋅tu⋅py /ˈäktəˌpī/ verb. To access and transform various institutions in an active yet constructive manner, with the dual goal of participating in and connecting with a shared goal. Picture from British Library Open Flickr account. British Library HMNTS 10492.ee.20. BUTTERWORTH, Hezekiah, 1891.

Promising steps towards more plural valuation practice are being taken. To octupy an institution (or institute) and shift its valuation focus to plural perspectives, one can apply some of these steps:

• Creating spaces for critical reflection on the normative assumptions behind valuation in order to gain awareness of our own positionality when practicing valuation (Horcea-Milcu et al., Reference Horcea-Milcu, Abson, Apetrei, Duse, Freeth, Riechers and Lang2019).

• Creating physical spaces and moments for nurturing plural values and forming alliances within existing disciplinary silos, to adjust current valuation practice.

• Developing new methods, best practices and networks for plural valuation across disciplines, age groups, and professional expertise.

• Strengthening science-policy-practice dialogues beyond disciplines, to improve horizontal learning and knowledge co-production. This means learning from each other, broadening the network of support and continuous investment in capacity building.

• Integrating local communities and capacities; connecting abstract concepts with local practices and integrating neglected voices while protecting intellectual property rights.

• Communicating in formal and informal contexts the development in thinking regarding plural valuation in order to engage a broader community.

As strategies have to be regularly adapted, octupation is only one step in realizing the full transformation towards plural valuation as a standard practice. Additionally, there is a need for mainstreaming and communicating successes, the development of authoritative global quality standards for plural valuation, compiling repositories of methods and guidance, developing value articulating institutions to empower neglected values, etc.

7. Power: it is up to us

Researchers and practitioners engaged in tackling sustainability challenges are becoming aware of both their power and their normative positions and the responsibility that comes with the exertion of such power. Valuation is more than just a technical job: it requires complex decisions about which problems to pursue, which funding to accept or distribute, who to include in research and decision-making, how to recognize their participation, which methods to choose and how to communicate the findings while upholding scientific rigor, inclusivity, transparency, intellectual property rights and critical thinking. As the ethics of these decisions also determines one's impact on the world, researchers and practitioners face difficult dilemmas that require trade-offs, compromises and hard choices. We hope that a clear vision, mission and the presence of a growing critical mass of plural valuation researchers and practitioners can offer support in making these choices.

In the end, the responsibility of valuation researchers and practitioners – including all of those who work in ‘assessment’ in the broadest sense – is to reflect upon the power they have. We are in a powerful position ourselves to engage in collective decision-making processes. It is up to us to decide what to do with that power.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of their peers in the diverse formal and informal networks who helped – and still help – to develop these ideas and advance the large and growing community. Especially noteworthy are the inspiring exchanges with colleagues in the extended networks of the OpenNESS project, the IPBES Assessments, the Ecosystem Service Partnership (ESP), SwedBio, Future Earth and the Program on Ecosystem Change and Society (PECS). The personal, real-life exchanges between scientists, policy-makers and practitioners in concrete local contexts have been instrumental in developing and pursuing plural valuation.

Author contributions

SJ and NZC compiled and edited the final paper and facilitated the collaborative writing process. PB, DG, LG and UP convened, organized and led the Oaxaca workshop that generated the information on which the paper is based. KB, AB, JC, SD, EG, SL, BML, VM, JM, HM, BM, AN, PO, JO, AP, AR, NS, MV and AHPR contributed to the generation of knowledge, information and perspectives during the plenaries and breakout sessions of the workshop, produced base material and reports of these sessions and discussions and co-authored by writing, revising, amending and validating all sections of the paper.

Financial support

The authors wish to thank the Sida-funded SwedBio programme at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, the Programme for Ecosystem Change and Society of Future Earth, the Gordon and Betty Moore University through sub-grant GBMF5433 to the Basque Centre for Climate Change (bc3) for supporting the undertaking of the workshop that led to this paper and the EQUIVAL project and the work of UP, PB and NZC, the Future Earth Montreal Global Hub, the Institute of Ecosystem and Sustainability Research at the Autonomous National University of Mexico and the Division of Science Policy and Capacity-Building (SC/PCB) of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), CISEN V, the ValuES project from GIZ supported by the BMUB and ecoSERVICES from Future Earth for providing support and financial resources. SJ wishes to thank the Flemish Department of Environment and Energy for funding a research stay under the Flanders–Basque Country Declaration of Intent.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The manuscript is our own original work, and does not duplicate any other previously published work; the manuscript has been submitted only to the journal – it is not under consideration, accepted for publication or in press elsewhere. All listed authors know of and agree to the manuscript being submitted to the journal; and the manuscript contains nothing that is abusive, defamatory, fraudulent, illegal, libellous or obscene.