The judicial dialogue between national courts and the European Court of Justice as a cornerstone of European constitutionalism – The importance of understanding how place-based identities shape national judges’ willingness to apply EU law and enter into dialogue with the European Court of Justice through the preliminary reference procedure – An interdisciplinary approach for studying lawyers and judges’ legal consciousness and sense of place-attachment – Geospatial and interview evidence of how national lawyers and judges’ participation in the preliminary reference procedure is influenced by their attachment to particular court settings and cities – Consequences for European constitutionalism and future research on the uneven judicial protection of EU rights.

Introduction: the spatial foundations of European constitutionalism

All social action unfolds across space: that much generates so little debate that it constitutes something of a truism. But until recently, few scholars seriously grappled with how legal practice and the ‘social life of constitutions’ – the degree to which social actors take constitutions for granted in lived experienceFootnote 1 – are equally rooted in and structured by place. In this view, space is not merely a stage upon which social action unfolds or a coordinate grid upon which legal authority can be arranged. When legal and social actors interact with one another at particular times and in particular locations, those sites can become repositories of meaning and frameworks through which individuals embrace (or eschew) particular constitutional practices. Geographic spaces become socio-legal places that empower, constrain, and constitute behaviour.

This article argues that a place-based ontology of the socio-legal world can advance the study of European constitutionalism, particularly our understanding of national courts’ dialogue with the European Court of Justice via the preliminary reference procedure (Article 267 TFEU).Footnote 2 Existing studies have underscored how the preliminary reference procedure served as the engine through which the Court of Justice ‘constitutionalised’ the Treaties by proclaiming that they established a ‘new legal order’ endowing individuals with directly enforceable rights before national courts, protecting fundamental rights, and holding primacy over conflicting national law.Footnote 3 Yet scholars have been less attentive to how and why national judges’ dialogue with the European Court has proven a remarkably uneven ‘process structured across space and time’.Footnote 4 As Antoine Vauchez puts it, ‘we [thus] find ourselves ill-equipped as we lack the geographic and social map of EU law’s embeddedness in European societies’.Footnote 5 The implications for European constitutionalism are notable. Given the EU’s limited bureaucratic and enforcement capacity, where and how national judges apply EU rules and refer cases to the Court of Justice is of a piece with where the EU’s claims to constitutional authority on paper are translated into concrete practice.Footnote 6 And given that national courts serve as the primary transmission belts linking civil society with European judges, their dialogue with the European Court anchors where and how citizens’ EU rights are most likely to be ‘made real’Footnote 7 and procured effective, multi-level judicial protection.Footnote 8

To be sure, legal scholars have documented divergent patterns of domestic judicial engagement with the European Court, with a particularly rich literature focused on the behaviour of national supreme courts anchored in distinct constitutional traditions.Footnote 9 Complementarily, social scientists have uncovered varying patterns of domestic judicial participation in the preliminary reference procedure, most recently through the innovative use of geospatial data.Footnote 10 Yet as I will show, these studies have neglected a crucial piece of the puzzle: they have yet to grapple with how place itself situates the legal consciousness of national lawyers and judges and, in so doing, conditions their willingness to engage the Court of Justice to faithfully apply EU law.Footnote 11 What do we stand to gain by rethinking European constitutionalism not only as a set of laws, principles, and practices, but also as a set of places?

This article tackles this question by unpacking the spatial foundations of how national judges differentially respond to the European Court’s call to jointly enforce the ‘basic constitutional charter’ of a transnational ‘community based on the rule of law’.Footnote 12 I do so by proposing and justifying an interdisciplinary framework for the study of European constitutionalism that empowers scholars to scale down to the subnational level and trace how place shapes the ways that national judges construct their positionality vis-à-vis the EU legal field and the Court of Justice. I then illustrate the practicality and utility of this approach by triangulating between geocoded maps of all preliminary references to the European Court through 2013 and hundreds of interviews conducted over 15 months of field research in French, Italian, and German courts.

In this endeavour, I focus particular attention on the behaviour of lawyers and judges practising within lower national courts, for two reasons. First, it is at the street-level of lower courts that most European citizens have the opportunity to come into direct contact with EU law and become cognisant of its everyday impact.Footnote 13 This means that local courts are wellsprings of European constitutionalism’s social life, a fact that the European Court has repeatedly recognised by stressing that even the humblest local courts ought to think of themselves as the cornerstones of a transnational European judiciary.Footnote 14 Second, unlike supreme or constitutional courts, in most instances lower courts have the discretion – but not the legal obligation – to avail themselves of the preliminary reference procedure when they doubt the interpretation of EU law.Footnote 15 This legally-permitted discretion provides greater scope for behavioural diversity, which in turn empowers scholars to assess whether the place-based identities of judges and lawyers condition how lower courts engage EU law and the Court of Justice.

To this end, I first use geospatial mapping to visualise the striking degree of local variation in national courts’ dialogue with the European Court. Then, instead of replicating existing studies that probe how such patterns correlate with other quantitative indicators,Footnote 16 I integrate a more field-intensive and ethnographic approach that has hitherto been neglected in existing scholarship. By drawing on illustrative examples from semi-structured interviews, I suggest that spatial patterns in national courts’ participation in the preliminary reference procedure are partly undergirded by the place-based identities of local judges and lawyers. I trace how judges ensconced in work-loaded lower courts tend to perceive a dialogue with the European Court as impractical, and these feelings can calcify into institutionalised court cultures wherein judges resist encounters with EU law. While these resistances can be eroded where lawyers repeatedly mobilise and invoke EU law, attorneys exhibit a distinct ‘place attachment’ of their own.Footnote 17 In resource-scarce client markets, lawyers perceive their communities as marginalised by EU law, and EU legal practice as professional suicide. Conversely, lawyers in wealthier and transnationally-interconnected ‘global cities’Footnote 18 perceive that such sites render mobilising EU law and the Court of Justice a professional necessity, and they transmit this situated legal consciousness to judges within local courts. By either integrating or partitioning European constitutionalism from local lived experience, lawyers and judges do not so much showcase why calls to ‘streamlin[e] the vertical cooperation with the European Court under the preliminary reference procedure’Footnote 19 are normatively undesirable, as some constitutional pluralists maintain.Footnote 20 Rather, they embody why such calls for uniformity may be empirically unrealisable in the first place.

The rest of this article is organised into four sections. I first theorise the foundations for the place-based study of socio-legal practices generally and European constitutionalism specifically. I then propose a methodology to unpack how place mediates the dialogue between national courts and the European Court and map the subnational distribution of preliminary references over time. Next, I draw on interviews conducted with lawyers and judges in Italy, France, and Germany to suggest how place-attachment undergirds these spatial patterns. Finally, I conclude with the implications for European constitutionalism and by suggesting pathways for future research.

Taking place seriously

The starting point of this article is a place-based ontology for socio-legal inquiry. By ontology, I mean ‘the character of the world as it actually is… [including] the fundamental assumptions scholars make about the nature of the social and political world’.Footnote 21 A place-based ontology can take two forms. A realist ontology would treat place as a reality that ‘exist[s] outside the mind’ by presuming that places are meaningful objects ‘independently of any consciousness’.Footnote 22 A phenomenological ontology would instead treat place as a social construction that shapes meaning-making. Here ‘place… becomes a basis for commonality in the life worlds of participants, which helps make their validity claims recognisable, tangible, indeed real to one another’.Footnote 23

In this article, I assume that what is objectively real – space – only becomes real in a social sense – place – once it becomes a meaning-laden referent through which people make sense of the world around them. Specifically, I am interested in the process whereby the material world becomes a frame for identity and action in the socio-legal world.Footnote 24 This approach borrows both from geographers and legal historians – for whom place functions as ‘a here from which to discover the world, a there to which we can return’Footnote 25 – as well as political scientists and sociologists – for whom ‘place matters’ because ‘it is a part’ of people’s ‘sense of self’.Footnote 26

While this place-based ontology is broadly interpretive, it can be used to analyse socio-legal practices whose consequences are very real. The point is that we should not presume that these practices are epiphenomenal of an objective or material reality that can ‘speak for itself’. People’s place-based perceptions shape their behaviour – and hence socio-legal outcomes – even if their empirical premises are false. Mark Blyth puts this point well: ‘So long as something… is believed by a large enough group of people, then because they believe it, it becomes true… Ideas therefore do not “really” need to correspond to the “real” world in order to be important in that world’.Footnote 27

In sum, for physical spaces to structure observable socio-legal behaviour, they must be converted and sometimes refracted into semiotic places by their inhabitants. They must come to constitute those ‘webs of significance’ that are taken for granted as ‘local knowledge’.Footnote 28

It might seem paradoxical or even radical to suggest that an ontology stressing place and local knowledge is necessary for making sense of constitutionalism and the practices of actors like lawyers and judges. After all, the field of law comports what Pierre Bourdieu describes as a ‘universalisation effect’, establishing ‘convergent procedures… reference to transsubjective values presupposing the existence of an ethical consensus… and the recourse to fixed formulas and locutions, which give little room for any individual variation’.Footnote 29 But as Bourdieu recognised and socio-legal scholars have long demonstrated, this view amounts to more of a legitimating myth or a ‘universalizing attitude’Footnote 30 than it does a social fact. Lawyers are embedded in particular societies, they adopt ‘varieties of professionalism in [legal] practice’ and forms of legal consciousness that are highly ‘situated’.Footnote 31 Judges too are ensconced in heterogeneous ‘material, textual, and graphic environment[s]’ that shape ‘the making of law’ and engender distinct ‘court cultures’ tied to particular times and institutional configurations.Footnote 32

Fine, but what about the EU? The universalising imperative of law is particularly powerful in Europe, since even in times of political and economic crisis, the EU remains ‘nowhere as real as in the field of law’.Footnote 33 Through at least the 1980s it was widely assumed that national judges had converged upon a uniform repertoire for the application of EU law and the solicitation of the European Court. This prompted Joseph Weiler to lament that ‘it is probably on this basis that one hears all too frequently all encompassing suggestions to improve the [reference] procedure… as if the problems one had with the application of the procedure were always uniform across the board’.Footnote 34

Yet over time even the insiders of the EU legal field – those whom we would most expect to adopt a ‘universalizing attitude’ – have come to reckon with reality. As Roger Grass – a French judge and longtime former registrar at the European Court – confides, ‘one might have thought that there would be a spirit of enthusiasm [in national judges], that our frontiers would blow away! And yet no, no, no… this is rather striking’.Footnote 35 Grass’s observation aligns with a burgeoning literature tracing how EU law does not cascade atop ‘a tabula rasa, but on an institutional terrain populated by preexisting legal orders’ that may resist their own displacement.Footnote 36 Like other multi-level and transnational legal orders, both the EU and the Court of Justice depend upon fertile ‘terrains’ and on-the-ground ‘compliance constituencies’ to ‘translat[e] international law into local practice’.Footnote 37 An ontology sensitive to place empowers the scholar to trace how site-specific legal consciousness mediates this process of translation, producing a ‘variable geometry’Footnote 38 of tangos between national courts and the Court of Justice. The implication is that the European Court’s ‘juris touch’Footnote 39 within the member states – and the EU’s claims to constitutional authority – is more patch-worked and contingent than universal and entrenched.

To a certain extent, this conclusion has been implicit from the moment scholars detected variation in the domestic implementation of EU law.Footnote 40 For instance, numerous studies have probed inter-state and inter-issue variation in national judges’ willingness to enforce EU rules and enter into dialogue with the European Court. They suggested that national constitutional traditions (common vs. civil law) and orientations to international law (dualism vs. monism),Footnote 41 as well as country levels of inter-EU trade,Footnote 42 population,Footnote 43 civic associationalism,Footnote 44 and business density,Footnote 45 may explain such variation. Others focused on variation across national judicial hierarchies, comparing the propensity to submit preliminary references of national courts of first and last instance.Footnote 46 All of these studies imply that the claims to transversal authority of EU law and the European Court’s rulings does not so percolate into national judicial practice.

Yet the foregoing studies never truly advanced theories derived from a place-based ontology of the social world. They tended to take the state for granted as the spatial unit of analysis, oftentimes – it must be said – for the pragmatic reason that country-level data tends to be available and relatively complete. They did not wrestle with whether the state – as opposed to alternative scales above and below the state – is most appropriate for understanding national courts’ dialogue with the Court of Justice.Footnote 47 And perhaps most importantly, they treated ‘place’ in its thinnest and least substantive form: as a unit of analysis or ‘data container’, to borrow Giovanni Sartori’s terminology.Footnote 48 As a result, the emergent story tended to centre on factors that just happened to be distributed across space. They did not probe whether lawyers and judges interpret their relationship vis-à-vis EU law and the European Court through the lens of the places they inhabit.

Aligning epistemology to a place-based ontology

If we are to take seriously the role that place can play in the dialogue between national and European judges, we need a suitable epistemology – a theoretical understanding of ‘how we know what we know’ – and methodological repertoire – the concrete ‘techniques or procedures used to gather and analyze data’.Footnote 49

‘Ontological issues and epistemological issues tend to emerge together’, because our assumptions of what the socio-legal world looks like favours particular modes of inquiry over others.Footnote 50 But when a more complex, fine-grained, or in any case novel ontology emerges, it risks ‘outrun[ning] both our methodologies and standard views of explanation’.Footnote 51 This is what Peter Hall refers to as the problem of ‘aligning ontology and methodology’.Footnote 52 When ontology and epistemology are misaligned, our standard methodological repertoire does not do justice to the ways we imagine the world to work. Yet such moments also constitute opportunities for ‘creative destruction’Footnote 53 and the advancement of knowledge. In my view, we are in the midst of such a misalignment in the study of European constitutionalism.

This claim acknowledges and seeks to borrow insight from a broad spatial turn in the social sciences. In the fields of comparative politics and sociology, for instance, there are mounting calls to ‘scale down’ and probe subnational dynamics neglected by more state-centric approaches.Footnote 54 Scholars of social movements, the information society, and legal sociology increasingly incorporate issues of ‘scale’ and ‘scale shift’ in their analyses.Footnote 55 Similarly, research on transnational legal orders and European integration increasingly embraces epistemologies that de-centre the national state to unpack local and transnational dynamics.Footnote 56 Yet the literature on the interactions between the European Court and national judiciaries has been slow to heed the call for epistemological realignment.

In this light, scholars of European constitutionalism would benefit from being more self-conscious about issues of spatial scale, including by making use of a tool – Geographic Information Systems technology – that was never used to study EU law until the last few years. Once a scale and unit of spatial analysis has been selected, the researcher can then conduct targeted fieldwork within selected units to trace how judges and other legal actors’ sense of place shapes how they invoke European law and whether they engage the Court of Justice via the preliminary reference procedure.

The first step requires grappling with what geographers term the ‘modifiable areal unit problem’.Footnote 57 This concept was developed by Stan OpenshawFootnote 58 and refers to the fact that spatial correlations ‘changed when smaller units were aggregated to form larger areal units’. It is exacerbated by the frequent arbitrariness of areal units and the plurality of ways that jurisdictional boundaries can be drawn.Footnote 59 The modifiable areal unit problem can lead researchers to make ecological fallacies, whereby micro-level behaviour (for example national judges’ propensity to submit preliminary references) is inferred from data organised at a larger spatial scale (for example country-level preliminary reference statistics).Footnote 60 Two conclusions readily follow. First, absent a preponderance of theoretical reasons to select one spatial scale over another, smaller units of analysis should be preferred over aggregate units. In other words, there is good reason to insure against the threat of ecological inference by scaling down to the subnational level. Second, an informed and inductive use of Geographic Information Systems technology can help us determine which spatial scale may be most appropriate.

The use of Geographic Information Systems technology is possible because the European Court’s case law database includes information on which national courts submit preliminary references. As result, these data can be geocoded on the basis of the city location of the referring court, enabling us to map the dialogue between the Court of Justice and national courts across time and space.Footnote 61 For instance, heat maps can be created from preliminary reference datasets using kernel densities – an algorithm calculating the density of geocoded point features (preliminary references) within a given search radius, fitting a smoothly curved surface over each point (where brighter or ‘hotter’ regions denote a greater density of reference activity).Footnote 62 Statistical measures of local spatial autocorrelation can also be used. Incremental spatial autocorrelation analysis, for instance, can identify the distance that maximises clustering in preliminary reference activity. Preliminary references can also be aggregated into polygon grids (or administrative jurisdictions, though these may be neither uniform nor comparable) to compute the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic. The statistic measures the presence of significantly higher (or lower) polygon values (number of national court referrals) within a fixed distance band around each polygon compared to the global mean.Footnote 63 These areas can then be mapped and classified as ‘hot spots’ and ‘cold spots’, denoting where national courts tend to enter into dialogue most often with the European Court.

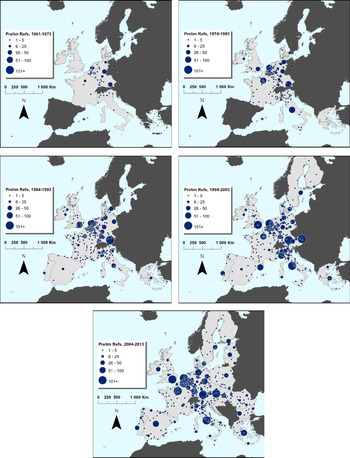

Even without resorting to spatial statistics, mapping preliminary references over time is sufficient to convey the extent to which national courts’ dialogue with the Court of Justice has varied at the subnational level. Figure 1 leverages a geocoded dataset of preliminary references from national courts across all EU member states from 1961 through 2013 to visualise their evolving spatial distribution.Footnote 64 These data are displayed as graduated point symbols, where larger circles denote more references from a given location.

Figure 1: Spatial distribution of preliminary references to the European Court of Justice from national courts across all EU member states, 1961-2013

Note: EU member states are denoted in lighter grey shading. Some states in light grey shading held EU membership for only part of the decade intervals in the maps. For instance, the UK, Denmark, and Ireland are shaded in light grey in the first map because they acceded to the EU on 1 January 1973, which falls within the 1961-1973 interval.

The maps in Figure 1 suggest that cities and broader metropolitan regions may serve as a particularly fertile scale for probing the spatial foundations of the dialogue between national courts and the European Court. Consider, for instance, the evolution of national courts’ preliminary references across three of the six founding member states of the EU: Italy, France, and Germany. In France, hardly any national court outside of Paris solicited the European Court through the 1980s. In Germany, by contrast, courts located across several large cities – Hamburg, Munich, Frankfurt, and Cologne – began to interact with the Court of Justice in earnest, and have continued to do so to the present day. Italy displays yet another type of spatial geography, one that bears some resemblances to France – in that courts located in the capital city of Rome have submitted the greatest share of references – but also to Germany – for judges working in number of cities across northern Italy like Milan, Genoa, Turin, and Venice also have regularly solicited the European Court.Footnote 65

Maps like these are useful pedagogically: it is one thing to speak of variable geometries, but it is quite another to see them on a map. Particularly in light of the profusion of statistical methods in empirical legal studies, it is worthwhile to remember that ‘[h]uman beings are better at interpreting data when it is displayed visually than when it is organised, for example, in tables or arrays of numbers’.Footnote 66

Yet crucially from the standpoint of research design, such maps are equally helpful for complementing quantitative analyses with comparative case studies and field-intensive methods. They do so by facilitating what social scientists and socio-legal scholars refer to as ‘case selection’. For just as the selection of spatial scales can shape our inferences, so too can ‘the cases you choose affect the answers you get’.Footnote 67 Even once a researcher has settled upon a scale – say, the metropolitan city – it matters which particular cases defined by said scale are chosen for more intensive research. For instance, only visiting capital cities where national courts have long been in dialogue with the Court of Justice – like Paris or London – may lend itself to making some inferences that fail to travel to other contexts or that omit important factors obstructing the dialogue between national and European judges.

One way to alleviate the threat of selection bias is to select multiple cases exhibiting variation in the outcome of interest, i.e. the propensity of local judges to make use of the preliminary reference procedure. For instance, John Stuart Mill’s methods of agreement and difference seek to maximise covariation between the outcome and the explanatory factors of interest across cases, and they are widely deployed in comparative sociology.Footnote 68 Using maps to visualise these covariations can help scholars identify which sites are particularly promising for conducting interviews, participant observation, or archival work.

Tracing place-attachment and situating the legal consciousness of national judges

Pairing large-N and geospatial analyses with fieldwork and case study research is especially fruitful for unpacking the spatial foundations of European constitutionalism generally and the preliminary reference procedure specifically. Although most existing empirical research on preliminary references tends to exclusively rely on quantitative methods, without also relying on qualitative and field-intensive research we are unable to ‘process trace’Footnote 69 how national judges relate to EU law and the European Court, and whether their place-attachments may play an important role. If place matters in understanding the dialogue between national and EU judges, we would expect legal actors in cities where lots of preliminary references originate to harbour a very different legal consciousness from those inhabiting cities where courts never interact with Luxembourg. We would expect their orientations to the EU legal field to be mediated by local knowledge and a place-based identity.

To this end, as part of a larger multi-year project probing how Italian, French, and German judges make use of the preliminary reference procedure, I conducted 15 months of fieldwork and over 300 interviews across dozens of national courts in 12 cities from 2015 to 2018. My primary interview strategy was to tap judges’ local knowledge via snowball sampling: person-to-person referrals (or snowballs) have been praised for producing findings that are both ‘emergent’ and ‘interactional’ through flexible face-to-face engagement. Snowballing forced me to meet a greater number of judges than I might have otherwise contacted and improved my sense of how judges perceive one another and the ways most colleagues act and think.Footnote 70 To then guard against getting stuck in a closed network of like-minded judges, I leveraged a comparative fieldwork approach: I deliberately sought to counterbalance interviews conducted in cities where local courts submitted the greatest number of preliminary references to the European Court over the past six decades (cities like Rome, Hamburg, Paris, Munich, and Milan) with fieldwork in comparably large cities witnessing very few national court referrals (Marseille, Bari, Naples, and Palermo). My goal here is to draw from interview transcripts to provide illustrative examples of how the behaviour of judges vis-à-vis the Court of Justice can become situated by a sense of place attachment. As such, the analysis that follows serves as a mere prolegomenon for future field-intensive empirical research on the social life of European constitutionalism.Footnote 71

For reasons of space, I limit my empirical examples to two. First, I suggest that everyday work routines within the built spaces of lower national courts obstruct judges from developing a legal consciousness open to a dialogue with Luxembourg. Second, I trace how this institutionally-embedded legal consciousness can be eroded where lawyers repeatedly invoke EU law before local courts, congruent with recent studies on how ‘Euro-lawyers’ can serve as legal entrepreneurs and architects of European constitutionalism.Footnote 72 Nevertheless, lawyers harbour and transmit place-attachments of their own. Where client markets are atomised into individuals and small local businesses, lawyers perceive specialising in EU law as a waste of time and often convey a sense that their community is marginalised within the European legal order. Conversely, in cities where lawyers can tap into a fabric of wealthy, transnational clients, they convey that specialising in EU law and agglomerating into large ‘Euro-firms’Footnote 73 is a professionally necessity in communities like theirs. When they then practise before local courts, judges become more open to soliciting the Court of Justice and to seeing themselves as part of a transnational European judiciary.

The first type of place attachment – of judges to the everyday practices within the office spaces of national courts – suggests how the material architecture of law’s adjudicationFootnote 74 can be endowed with meaning and constrain European constitutionalism. That is, it suggests one reason why very few national courts ever solicit the European Court through the preliminary reference procedure in the first place. Consider the claustrophobic portrait conveyed by a first-instance judge in Milan:

‘The judge should have an enormous amount of time to study, but today this isn’t possible. So many judges don’t come [to EU training sessions] because on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday they hold hearings, on the afternoons they must write the judgments, they must attend section conferences, they have administrative duties to tend, and in this bureaucratic silence EU law dies’. Footnote 75

What this judge is highlighting is a form of consciousness tied to everyday labour routines within lower national courts, which become hostile places for EU law to take root. When these notions become entangled ‘in particular sites and at particular times’, they can calcify into a cognitive constraint upon new ways of knowing and doing EU law. Footnote 76 To wit, ‘everyday practices within domestic judiciaries stemming from insufficient training in European Union law’ combined with site-specific ‘workload pressures’ can foment a sense of distance and even neglect vis-à-vis the European Court.Footnote 77

This consciousness is deeply situated in institutional place, as exemplified by judges who describe its contours under the presumption that similarly situated colleagues will also deem it ‘impossible’ to interact with the Court of Justice. They speak in terms of a ‘we’ rooted ‘here’. Exemplary are the following remarks by a French lower court judge. Speaking for herself and her colleagues, she confides that crafting a referral to Luxembourg is broadly perceived as

‘not something you can do when you’re at the court of appeal or a first instance court… Here it’s impossible… to refine a preliminary reference, to review all the jurisprudence of the European Court etc, for all of that, there would be 10 or 15 case files that will have accumulated… Already we often have to work on weekends, so it’s difficult to find the space….’Footnote 78

This consciousness becomes even more rooted in place when judges are not regularly solicited and assisted by local lawyers in the application of EU law. Consider excerpts of a conversation with a group of judges at the Marseille civil court:

‘All the EU regulations – we apply little, because there’s little litigation, I think, here in Marseille… It’s true that we can submit a preliminary reference [to the European Court], but it’s not in our DNA to solicit an interpretation of the Court of Justice… This perhaps demonstrates that in the end European law is… scarcely applicable in the quotidianity of the judge. I also think that it’s because of this that we don’t apply it… Marseille has an extremely difficult economic life… so, there’s certainly business lawyers in Marseille but we don’t see them in court’.Footnote 79

This perspective also expresses itself spatially when judges transpose a vertical sense of distance to EU law and its claims to primacy into a horizontal opposition to cities where EU law is regularly practised. Judges across my interviews frequently pitted a ‘here’ against a ‘there’ where Euro-lawyers cluster and colleagues regularly solicit the European Court. Often nestled within this place-based consciousness is a feeling of distributive injustice and neglect, as illustrated by a conversation with two administrative judges in Palermo:

‘It also depends upon the differences between us and Milan. If you just look at the average worth of disputes, the type of litigation… In Milan I participated in a conference last month on the impact of EU law upon national administrative law. Eh! They’re well-equipped there’.Footnote 80

These binary oppositions were often referenced by colleagues who perceived their communities to be at the margins of globalisation and the EU legal order: they frequently lamented how EU law specialists ‘unfortunately, don’t come from our territory’ and resigned themselves to the fact that when it comes to engaging the Court of Justice and mobilising EU law, ‘the bar that matters isn’t ours’.Footnote 81 But the reverse perspective also holds in wealthier transnational hubs – or what sociologist Saskia Sassen would call ‘global cities’.Footnote 82 For instance, one Parisian administrative judge explains that

‘in Paris we refer more cases to the European judges… in truth we have a bar that is more competent, if you will, than in other cities… here are lots of specialised law firms, lots of Anglo-Saxon firms… this plays a big role, and it explains the numeric concentration of preliminary reference questions from the Paris region… [for] if the lawyers don’t think about raising these questions, then we won’t respond to them and there won’t be a preliminary reference to the European Court of Justice’.Footnote 83

These comments confirm the fertility of what Jos Hoevenaars terms a ‘bottom-up’ approach to studying the preliminary reference procedure and the effective judicial protections of EU rights.Footnote 84 Lawyers are not only described by judges as crucial bottom-up ‘motors’ behind their willingness to solicit the European Court:Footnote 85 they also root judicial practice and become carriers of a place-based legal consciousness. Over the course of fieldwork, I repeatedly encountered lawyers whose willingness to mobilise EU law before national courts hinged on their sense of whether it would constitute a professional necessity or professional suicide in a place like theirs. In other words, their place-based identity induces a sort of ‘consciousness isomorphism’Footnote 86 travelling from lawyers in the bar to judges on the bench.

Consider the poignant view of a young EU law specialist practising in Palermo. After completing his studies and interning at the European Commission, he returned to his home city to practise EU law. His enthusiasm was quickly quashed as he was forced to reckon with a diffuse and deeply rooted place-based identity:

‘When you came back here, you felt strangely alone. It’s an incredible sensation, right?… You realised that here, as you spoke to friends and lawyers, you were a sort of extraterrestrial… People say: “All right, he does international law, what the heck is he doing here?”’Footnote 87

Like their judicial interlocutors, lawyers in depressed client markets express a sense of distance from EU law and of relative deprivation, opposing a ‘here’ to a ‘there’ where corporations, Euro-firms, and preliminary references agglomerate. Representative are the acerbic remarks of a lawyer in Marseille, who mocked his younger colleagues who specialise in EU law: ‘These masters [degrees] provide them with expertise in areas where they’ll never find a client! … What are those people doing here? … They should head to Paris’.Footnote 88

Lawyers practising in wealthier client markets and embedded within large law firms corroborate this logic via a place-based consciousness of their own. When I spoke to a leading Euro-lawyer at Jones Day’s Paris office, he stressed how it is only in cities like Paris that one can enter an ‘incestuous… micro-world’ of lawyers and judges who ‘frequently meet up with each other’ and solicit the European Court, comprising a ‘social group… [that] I haven’t seen so much elsewhere’. After all, the lawyer adds,

‘EU litigation is lengthy and costly!… So who can pay for this? It’s the big businesses. This matters too! When you look at the conjunction of those lawyers who interest themselves in EU law – like your friend in Palermo, which is a really beautiful city – most will say: “I’m going to go to a law firm that will value my experience and my training, so I’m going to Paris, or London, or Brussels, or Frankfurt!”’Footnote 89

On occasion, lawyers in wealthier client markets even used notions of place to patronise their colleagues elsewhere. For instance, in a conversation held at the Hamburg office of a transnational law firm, an experienced Euro-lawyer quipped that ‘if you go to Palermo or Marseille, or I don’t know where, and the lawyers say “we can’t specialise as much in European law,” I want to re-emphasise, that statement in my mind is questionable… [for] European law is part of French and Italian law’.Footnote 90 Perhaps the most memorable invocation of place was offered by a leading EU law practitioner in Milan, who stressed the ‘geographic’ opposition of his city from ‘smaller hubs’ beset by ‘smaller law firms plus localisation in provincial space, [where] the result for EU law is that you plunge into an extraordinary black hole’.Footnote 91 It is not hard to see how these place-based identities can, however unwittingly, become self-fulfilling prophecies. That is, they can become legitimating logics for legal and judicial practices that reify the uneven reach of EU law and exacerbate the very inequalities being maligned.

Conclusion: putting European constitutionalism in its place

By combining a place-based ontology with geospatial analyses and on-site fieldwork, scholars of European constitutionalism can peel back the ways that EU rules and the European Court’s case law percolate within member states and produce variable geometries of judicial enforcement.Footnote 92 Putting this approach into practice, I provided initial evidence to illustrate that the spatial characteristics of particular cities and judicial settings can be reworked into a place-based identity that conditions lawyers’ and judges’ engagement with EU law and the European Court of Justice.

This socio-legal process of interpretation and translation significantly impacts the promise of European constitutionalism. It shapes where and how the EU’s claims to constitutional authority are ensconced in street-level judicial practices within member states through the transmission belt supplied by the preliminary reference procedure. A sense of attachment to a particular place – a here in the form of this court, this city, this bar – can both facilitate and obstruct national courts’ dialogue with the Court of Justice, but in either instance it acts as a mediating and refractive force.

Since place situates the legal consciousness of national lawyers and judges, it also impacts citizens’ access to Europe’s multi-level system of judicial protection. This matters because national judiciaries – and lower courts in particular – are places where perceptions of a distant, out-of-touch political authority are either contradicted or confirmed. In this light, a few courts gain a reputation for being hubs where the direct applicability of EU law is recognised and reigns supreme. Yet many other courts come to symbolise bastions of nationally-oriented judicial practices where EU’s legal authority – let alone the European Court’s call to enforce a basic constitutional charter – is hard to detect. A few cities become symbols for specialised Euro-lawyers and large law firms ready to activate the judicial protection of citizens’ and businesses’ EU legal rights (for a price). Yet many other communities are instead treated by lawyers and judges as ‘deserts’Footnote 93 of EU law where soliciting the Court of Justice is either impractical or impossible.

However sobering, these findings also open fruitful avenues for research. First, although this article is wholly consistent with existing econometric studies linking preliminary reference rates to wealthier population centres and hubs of intra-European trade, it also suggests that there are important interpretive and behavioural processes that undergird these correlations. Lawyers and judges do not live in a world of variables dissociated from local context and knowledge. Rather, they interpret their world holistically, and if we are to explain their behaviour than we must take seriously how factors such as wealth, trade, and population can morph into place-based identities that mediate national courts’ engagement with the EU legal order. Undoubtedly, much important work remains to be done to unpack this process.

Second, although this article corroborates constitutional pluralist arguments that there is more diversity than ‘ever more uniformity’ to be found in the functioning of the EU legal order,Footnote 94 it also highlights how pluralism has a darker side worthy of study. Taking judges’ place-attachment seriously becomes a way to probe how diverse judicial practices can produce inequalities that – at least in some places – work to ‘contain’Footnote 95 the European Court’s promise in Van Gend en Loos to ‘confer upon [individuals] rights which become part of their legal heritage’.Footnote 96

Finally, this article suggests that a closer engagement between studies of European constitutionalism and social science research on the role of place-based identity politics would be decidedly productive.Footnote 97 Like other social actors, judges’ attachment to particular places can shape their sense of self, their orientations to the law, and their willingness to submit to or resist claims to constitutional authority by transnational polities like the EU. A growing literature indeed argues that the EU’s political development requires the cultivation of a ‘banal’ European identity that becomes taken for granted by local actors in their everyday life.Footnote 98 This insight not only holds for citizens and civil society in the political arena: it also applies to jurists in the legal arena.Footnote 99 By taking lawyers and judges’ place-attachment seriously, scholars of European constitutionalism are uniquely placed to reconstruct an understudied yet critical dimension of the EU’s tortuously patchworked political development.