All drug use, fundamentally, has to do with speed, modification of speed … the times that become superhuman or subhuman.

After all, the world is industrial and we have to come to terms with it … Gone are the old good days of opium, heroin, gone are the young bangi¸ gone is hashish, marijuana, and geraas [weed, grass]! Now it is all about shisheh, blour and kristal and nakh. The modern people have become post-modern. And this latter, we know, it is industrial and poetical, like the God’s tear or Satan’s deceit.Footnote 1

Introduction

The election of Mahmud Ahmadinejad to the ninth presidency of the Islamic Republic asserted an anomaly within the political process of post-revolutionary, post-war Iran. After the heydays of reformist government, with its inconclusive and juxtaposing political outcomes, the 2005 elections had seen the rise of a political figure considered, up to then, as marginal, secondary, if not eclectic and obscure. Accompanied by his rhetoric, which tapped into both a bygone revolutionary era and a populist internationalist fervour, Ahmadinejad brought onto the scene of Iranian – and arguably international – politics, an energy and a mannerism, which were unfamiliar to Islamist and Western political cadres.

Considering his apparent idiosyncrasies, much of the attention of scholars and media went into discerning the man, his ideas and his human circles, with symptomatic attention to foreign policy.Footnote 2 His impact on the domestic politics of the Islamic Republic, too, has been interpreted as a consequence of his personalising style of government; his messianic passion about Shi’a revival and religious eschatology clashed with his apparent infatuation with Iran’s ancient Zoroastrian heritage;Footnote 3 and, significantly, his confrontational attitude vis-à-vis political adversaries manifested an unprecedented tone in the political script. Ahmadinejad himself contributed greatly to his caricature: his public appearances (and ‘disappearances’Footnote 4) as well as speeches, amounting to thousands in just a few years.Footnote 5 His interventions in international settings regularly prompted great upheaval and controversy, if not a tragicomic allure prompted by his many detractors. His accusations and attacks against the politico-economic elites were numerous and unusually explicit for the style of national leaders, even when compared to European and American populist leaders, such as Jair Bolsonaro, Donald J. Trump and Matteo Salvini, all of whom remain conformist on economic matters. Ultimately, his remarks about the Holocaust and Israel, albeit inconsistent and exaggerated by foreign detractors, made all the more convenient the making of Ahmadinejad into a controversial character both domestically and globally, while provided him some legitimacy gains and political latitude among hard-liners, domestically, and Islamist circles abroad. Philosopher Jahanbegloo, in his essay ‘Two Sovereignties and the Legitimacy Crisis’, describes this period ‘as the final step in a progressive shift in the Iranian revolution from popular republicanism to absolute sovereignty’.Footnote 6 Conversely, in this volume, Part Two and its three Chapters give voice and substance to this period and its new form of profane politics as they emerged after 2005. In its unholy practices, it did not produce enhanced theocracy, nor absolute sovereignty. Instead it made Iranian politics and society visibly profane, with its drug policy being the case par excellence. Jahanbegloo’s take, and that of other scholars following this line, has shed a dim light on the epochal dynamics shaping the post-reformist years (2005–13).Footnote 7 It is over this period that an ‘anthropological mutation’ took shape in terms of lifestyle, political participation, consumption and cultural order.Footnote 8 This anthropological mutation produced new social identities, which were no longer in continuity with neither the historical past nor with ways of being modern in Iran. This new situation, determined by ruptures in cultural idioms and social performances, blurred the lines between social class, rural and urban life, and cultural references among people. Italian poet, film director and essayist Pier Paolo Pasolini described the transformations of the Italian people during the post-war period – especially in the 1970s – as determined by global consumerism and not, as one would have expected, by the Weltanschauung of the conservative Christian Democratic party, which ruled Italy since the liberation from Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime in 1945. Not the cautious and regressive politics of the Catholic Church, but the unstoppable force of hedonistic consumerism represented the historical force behind the way Italians experienced life and, for that matter, politics. Taking Pasolini’s insight into historical, anthropological transformation, I use the term anthropological mutation – or, as Pasolini himself suggested, ‘revolution’ – to understand the epochal fluidity of Iranian society by the time Mahmud Ahmadinejad was elected president in 2005. It was not the reformist government alone that brought profound change in Iranian society. Reform and transformation were key traits of Ahmadinejad’s time in government. That is also why the period following Khatami’s presidency is better understood as post-reformism rather than anti-reformism.

Over this period, the Islamic Republic and Iranians all lived through the greatest political upheaval following the 1979 revolution: political mobilisation ahead of the June 2009 elections, especially with the rise of the Green Movement (jonbesh-e sabz); then state-led repression against protesters and the movement’s leaders, Mir Hossein Musavi and Mehdi Karroubi. The events following the presidential elections in June 2009 exacerbated the already tense conditions under which politics had unfolded in the new millennium. Allegations of irregularities, widely circulated in international and social media, led to popular mobilisation against what was perceived as a coup d’état by the incumbent government presided over by Ahmadinejad; then, the seclusion of presidential candidates Mir Hossein Musavi and Mehdi Karrubi, inter alios, changed the parameters and stakes of domestic politics irremediably. For the first time since the victory of the revolution in 1979, massive popular demonstrations took place against the state authorities. Meanwhile, the security apparatuses arrested and defused the network of reformist politicians, many of whom had, up to then, been highly influential members of the Islamic Republic. Echoing the words of president Ahmadinejad himself, he had brought ‘the revolution in the government’.Footnote 9

In this Chapter, I dwell on a set of sociocultural trends that unfolded during this period, progressively transforming Iranian society into a (post)modern, globalised terrain. It is important to situate these dynamics as they play effectively both in the phenomenon of drug (ab)use and the narrative of state interventions, the latter discussed in the next two Chapters. In particular, the ‘epidemic’ of methamphetamine use (shisheh), I argue, altered the previously accepted boundaries of intervention, compelling the government to opt for strategies of management of the crisis. The following three Chapters explore the period after 2005 through a three-dimensional approach constituted of social, medical and political layers. The objective is to examine and re-enact the micro/macro political game that animated drugs politics over this period. In this setting, drugs become a prism to observe these larger human, societal and political changes.

Addictions, Social Change, and Globalisation

With the rise of ‘neo-conservatives’ within the landscape of Iranian institutions, it is normatively assumed that groups linked to the IRGC security and logistics apparatuses, as well as individuals linked to intelligence services, gained substantial ground in influencing politics. The overall political atmosphere witnessed an upturning: religious dialogue and progressive policies were replaced by devotional zeal and ‘principalist’ (osulgar) legislations. Similarly, the social context witnessed epochal changes. These changes can be attributed in part to the deep and far-reaching impact that the reformist discourse had had over the early 2000s, in spite of its clamorous political failures. The seeds that the reformists had sowed before 2005, were bearing fruit while the anathema of Mahmud Ahmadinejad was in power. Longer-term processes were also at work, along lines common to the rest of the world. Larger strata of the population were thus exposed to the light and dark edges of a consumeristic society.Footnote 10 The emergence of individual values and global cultural trends, in spite of their apparent insolubility within the austerity of the Islamic Republic, signalled the changing nature of life and the public.

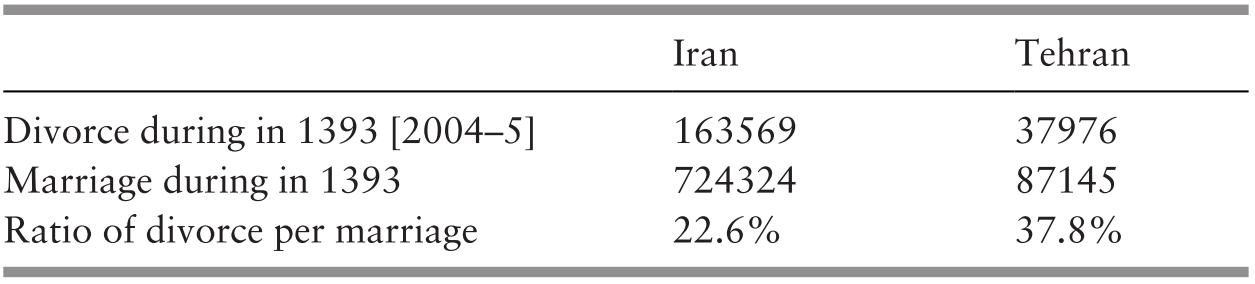

Family structure underwent a radical transformation during the 2000s. With rates of divorce hitting their highest levels globally and with a birth rate shrinking to levels comparable to, if not lower than, Western industrialised countries, the place of family and the individual was overhauled, together with many of the social norms associated with them (Table 6.1). The average child per woman ratio fell from seven in the 1980s to less than two in the new millennium, a datum comparable to that of the United States.Footnote 12 The (mono)nuclearisation of the family and the atomisation of individuals brought a new mode of life within the ecology of ever-growing urban centres. Likewise, the quest for better professional careers, more prestigious education (including in private schools), and hedonistic lifestyles, did not exclusively apply, as it had historically, to bourgeois families residing in the northern part of the capital Tehran. Along with Mahmud Ahmadinejad’s coming to power, rural, working class, ‘villain’ (dahati) Iranians entered the secular world of the upper-middle class, at least in their cultural referents.Footnote 13 More than ever before, different social classes shared a similar horizon of life, education being the ‘launch pad’ for a brighter career, made of the acquisition of modern and sophisticated products, such as luxury cars, expensive clothes, cosmetic surgeries, technological devices and exotic travels (e.g. Thailand, Dubai).Footnote 14 These elements entered surreptiously but firmly into the daily lexicon and imagination of working class Iranians, against the tide of economic troubles and the increasing visibility of social inequality.Footnote 15 A decade later, in the late 2010s, consumerism has become a prime force, manifested in the Instagram accounts of most people.

Table 6.1 Rates of Divorce in 2004–5Footnote 11

| Iran | Tehran | |

|---|---|---|

| Divorce during in 1393 [2004–5] | 163569 | 37976 |

| Marriage during in 1393 | 724324 | 87145 |

| Ratio of divorce per marriage | 22.6% | 37.8% |

Coterminous to this new popular imagery, the lack of adequate employment opportunities resulted from a combination of haphazard industrial policy, international sanctions and lack of investments, inducing large numbers of people to seek a better lot abroad. With its highly educated population, Iran topped the ominous list of university-level émigrés. According to the IMF report, more than 150,000 people have left the country every year since the 1990s with a loss of approximately 50 billion dollars.Footnote 16 After the clampdown on the 2009 protestors, many of them students and young people, this trend was exacerbated to the point of being acknowledged as the ‘brain-drain crisis’ (bohran-e farar-e maghz-ha).Footnote 17 A report published in the newspaper Sharq indicated that between 1993 and 2007, 225 Iranian students participated in world Olympiads in mathematics, physics, chemistry and computer science.Footnote 18 Of these 225, 140 are currently studying at top US and Canadian universities.Footnote 19 The case of the mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani, who, in 2014, was the first woman ever to win the Fields Medal (the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in mathematics), is exemplary of this trend.Footnote 20 In the words of sociologist Hamid Reza Jalaipour, ‘many left the country, and those who remained in Iran had to travel within themselves’,Footnote 21 by using drugs.

The presence of young people in the public space had become dominant and, in the teeth of the moral police (gasht-e ershad) and the reactionary elements within the clergy, exuberantly active. The fields of music, cinema, arts and sports boomed during the late 2000s and physically encroached into the walls and undergrounds of Iran’s main cities. The examples provided by Bahman Ghobadi’s No one knows about Persian cats (winner of the Un Certain Regard at Cannes) and the graffiti artist ‘Black Hand’ – Iran’s Banksy – are two meaningful cases in an ocean of artistic production of globalised resonance.Footnote 22

Considering the sharpening of social conditions, both material and imagined, there was a steady rise in reported cases of depression (dépréshion, afsordegi). Indicative of the growing mental health issue is a report published by the Aria Strategic Research Centre, which claims ‘that 30 percent of Tehran residents suffer from severe depression, while another 28 percent suffer from mild depression’.Footnote 23 Obviously, the increased relevance of depression can be attributed to a variation in the diagnostic capacity of the medical community, as well as to changes and redefinition of the symptoms within the medical doctrine.Footnote 24 Yet, the fact that depression progressively came to occupy the landscape of reference and human imagery of this period is a meaningful sign of changing perception of the self and the self’s place within broader social situations.

The lack of entertainment in the public space has been a hallmark of post-revolutionary society, but its burden became all the more intolerable for a young globalised generation, with expectations of a sophisticated lifestyle, and cultural norms which have shifted in drastic ways compared to their parents. If part of it had been expressed in the materialisation of an Iranized counterculture (seen in the fields of arts and new media), the other remained trapped in chronic dysphoria, apathy and anomie, to which drug use was often the response. The prevalence of depression nationwide, according to reports published in 2014, reaches 26.5 per cent among women and 15.8 per cent among men, with divorced couples and unemployed people being more at risk.Footnote 25 In a post-conflict context, characterised by recurrent threats of war (Israeli, US military intervention), the emergence of depressive symptoms is not an anomaly. However, as Orkideh Behrouzan argues, in Iran there is a conscious reference to depression as a political datum, manifested, for instance, in the popular expression ‘the 1360s (1980s) generation,’ (daheh shasti) as the ‘khamushi or silenced generation’ (nasl-e khamushi).Footnote 26 The 1980s generation lived their childhood through the war, experienced the post-war reconstruction period and the by-products of the cultural revolution, while at the same time gained extensive access – thanks to the unintended effects of the Islamic Republic’s social policies – to social media, internet and globalised cultural products.

An event that may have had profound effects on the understanding of depression among Iranian youth is the failure of achieving tangible political reforms following the window of reformism and, crucially, in the wake of the protests of the 2009 Green Movement. The large-scale mobilisation among the urban youth raised the bar of expectations, which clashed with the state’s heavy-handed security response, silencing of opponents and refusal to take in legitimate demands. In this, the reformists’ debacle of 2009 was a sign of a collective failure justifying the self-diagnosis of depression by the many expecting their actions to bear results.

In 2009, Abbas Mohtaj, advisor to the Ministry of Interior in security and military affairs said, ‘joy engineering [mohandesi-ye shadi] must be designed in the Islamic Republic of Iran, so that the people and the officials who live in the country can appreciate real happiness’. He then carefully added that ‘of course, this plan has nothing to do with the Western idea of joy’.Footnote 27 His call was soon echoed by the head of the Seda va Sima (Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting) Ezatollah Zarghami, who remarked about the urgency of these measures for the youth.Footnote 28 The government had since then relaxed the codes of expression in the radio, allowing satirical programmes (tanz), perhaps unaware of the fact that political jokes and satire had already been circulating via SMS, social media and the internet, in massive amounts. More extravagantly, the government called for the establishment of ‘laughter workshops’ (kargah-e khandeh), somehow remindful of the already widespread classes of Laughter Yoga in Tehran’s parks and hiking routes.

‘People should have real joy [shadi-ye vaqe’i]’, specified an official, ‘and not artificial joy [masnu’i] as in the West’.Footnote 29 Yet, more than ever before, Iranians ventured to trigger joy artificially, notably by using drugs, medical or illegal ones. Auto-diagnosis, self-care and self-prescription had become the norm among the population, preluding to a general discourse towards medicalisation of depression and medicalised lifestyles. With antidepressants being the most prescribed drugs and 40 per cent of Iranians self-prescribing,Footnote 30 one can infer the scope of this phenomenon and, particularly, its relevance on drug policy. The appearance of dysphoria and apathy, regardless of generational divide, is also manifested in the spectacular expansion of the professional activities of mental health workers, specifically, psychotherapists, whose services are sought by ever-larger numbers of people, although mostly belonging to the middle and upper classes.Footnote 31 Examples of depressive behaviour have often been connected to drug (ab)use. The expansion of Narcotics Anonymous (mo’tadan-e gomnam, aka NA, ‘en-ay’), and its resonance with the larger public, exemplified the transition that social life, individuality and governmentality were undergoing.

Other manifestations of this new ‘spirit of the time’ encompassed addictive behaviours more broadly. For instance, groups such the Anjoman-e Porkhoran-e Gomnam (Overeaters Anonymous Society), which appear as a meeting point for people suffering from compulsive food disorders, are on the rise with more than eighteen cities operating self-help groups.Footnote 32 Similarly, sex addiction surfaced as another emblematic phenomenon. In the prudish public morality of Ahmadinejad’s Islamic Republic, there were already medical clinics treating this type of disorder.Footnote 33 A Shiraz-based psychiatrist during the 2013 MENA Harm Reduction Conference in Beirut surprised me when he said that a large number of people had been seeking his help for their sex addiction and compulsive sex, both in Shiraz and Tehran. This, he argued, was in part caused by the increasing use of amphetamine-type stimulants, which artificially arouse sexual desire, but was also a sign for the displacement of values in favour of new models of life, often inspired by commercialised products, such as films, pornography, advertisements and social media.Footnote 34

Alcoholism, too, has been acknowledged by the government as a social problem. Today there are branches of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) in Iran and rehab centres for alcoholism, despite alcohol remaining an illegal substance, the consumption of which is punished severely. Beyond the diagnostic reality of these claims, it is undeniable that these changes occurred particularly during the years when president Ahmadinejad and his entourage were in government. Indeed, many of the policies and laws in relation to controversial issues, such as on transsexuality and alcoholism, took form during the post-reformist years.Footnote 35 These transformations occurred not as a consequence of the government’s performance and vision, but rather as a rooting and continuation of secular, global trends, many of which began during the reformist momentum, to which, awkwardly but effectively, the populist government concurred. This was a new mode of political and social change, one that could be called reforms after reformism. Once again, a counter-intuitive phenomenon was at play.

The ‘Crisis’ of Shisheh and Its Narratives

If one combines the widespread use of antidepressant drugs with the impressive rise in psychoactive, stimulant and energizing drugs, most notably shisheh, the picture inevitably suggests a deep-seated transformation in the societal fabric and cultural order during the post-reformist era.Footnote 36

In early 2006, officials started to refer to the widespread availability of psychoactive, industrial drugs (san’ati) through different channels, including satellite TVs and the internet.Footnote 37 They said they had little evidence about where these substances originated from and how they were acquired.Footnote 38 Although ecstasy – and generally ATSs – had been available in Iran for almost a decade, its spread had been limited to party scenes in the urban, wealthy capital.Footnote 39 The appearance of methamphetamines (under the name of ice, crystal, and most notably, shisheh, meaning ‘glass’ in reference to the glass-like look of meth) proved that the taste for drugs among the public was undergoing exceptional changes, with far-reaching implications for policy and politics.Footnote 40

The most common way to use meth is to smoke it in a glass pipe in short sessions of few inhalations. It is an odourless, colourless smoke, which can be consumed in a matter of a few seconds with very little preparation needed (Figure 6.1). In one of the first articles published about shisheh in the media, a public official warned that people should be careful about those offering shisheh as a daru, a medical remedy, for lack of energy, apathy, depression and, ironically, addiction.Footnote 41 By stimulating the user with an extraordinary boost of energy and positive feelings, shisheh provided a rapid and, seemingly, unproblematic solution to people’s problems of joy, motivation and mood. Its status as a new drug prevented it from being the object of anti-narcotics confiscation under the harsh drug laws for trafficking. After all, the official list of illicit substances did not include shisheh before 2010, when the drug laws were updated. Until then the crimes related to its production and distribution were referred to the court of medical crimes, with undistressing penalties.Footnote 42

Figure 6.1 Meanwhile in the Metro: Man Smoking Shisheh.

The limited availability of shisheh initially made it too expensive for the ordinary drug user, while it also engendered a sense of classist desire for a product that was considered ‘high class [kelas-bala]’.Footnote 43 As such, shisheh was initially the drug of choice among professionals in Tehran, who in the words of a recovered shisheh user, was used ‘to work more, to make more money’.Footnote 44 Yet after its price decreased sensitively (Figure 6.2), shisheh became popular among all social strata, including students and women, as well as the rural population. By 2010, it was claimed that 70 per cent of drug users were (also) using shisheh and that the price of it had dropped by roughly 400 per cent compared to its first appearance in the domestic market.Footnote 45 It was a ‘tsunami’ of shisheh use which took both state officials and the medical community unprepared, prompting some of the people in the field to call for ‘the creation of a national headquarters for the crisis of shisheh’, very much along the lines of the ‘headquartisation’ mentality described in the early post-war period.Footnote 46 This new crisis within the field of drug (ab)use was the outcome of a series of overlapping trends that materialised in the narratives, both official and among ordinary people, about shisheh. The narrative of crisis persisted after 2005 in similar, or perhaps more emphatic, tones.

This new substance differed significantly from previously known and used drugs in Iran. In contrast to opium and heroin, which tended ‘to break the spell of time’ and diminish anxiety, stress and pain, making users ultimately nod in their chair or lie on the carpet, methamphetamines generally boost people’s activities and motivate them to move and work, eliminating the need for sleep and food.Footnote 47 In a spectrum inclusive of all mind-altering substances, to put it crudely, opiates and meth would be at the antipodes. All drugs and drug use, wrote the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, have to do with ‘speed, modification of speed … the times that become superhuman or subhuman’.Footnote 48 Shisheh had to do with time, people’s perception of time’s flow; it was the new wonder drug of the century, with its mind-altering speed and physical rush as distinctive emblems of (post)modern consumption.

Opiates derive from an agricultural crop, the poppy, whereas methamphetamines are synthetized chemically in laboratories and therefore do not need agricultural land to crop in. Between 2007 and 2010, Iran topped the international table of pseudoephedrine and ephedrine legitimate imports, with quantities far above expected levels according to the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB).Footnote 49 Pseudoephedrine and ephedrine are both key precursors for meth production, the rest of the chemical elements being readily available in regular stores and supermarkets. With Iran’s anti-narcotic strategy heavily imbalanced towards its borders with Afghanistan and Pakistan, the production of shisheh could occur, with few expedients and precautions, ‘at home’. In fact, it did not take long before small-scale laboratories – ante tempore versions of Walter White’s one in Breaking Bad – appeared within borders, inducing the head of the anti-narcotic police to declare, ‘today, a master student in chemistry can easily set up a laboratory and, by using the formula and a few pharmaceutical products, he can obtain and produce shisheh’.Footnote 50 In 2010, the anti-narcotic police discovered 166 labs, with the number increasing to 416 labs in 2014.Footnote 51 The supply reduction operations could not target domestic, private production of meth, because this new industry was organised differently from previous illicit drug businesses and could physically take place everywhere.

The high demand for meth and the grim status of the job market guaranteed employment in the ‘shisheh industry’.Footnote 52 A ‘kitchen’ owner who ran four producing units in Southern Tehran revealed that the prices of shisheh had shrunk steadily because of the high potential of production in Iran. In his rather conventional words, ‘young chemical engineers, who cannot find a job … work for the kitchen owner at low prices’, and, he adds, ‘precursors and equipment are readily available in the capital’s main pharmaceutical market at affordable prices’.Footnote 53 The shisheh that is produced is sold domestically or in countries such as Thailand under the local name of yaa baa, or Malaysia and Indonesia, where there is high demand for meth. The number of Iranian nationals arrested in international airports in Asia hints clearly at this phenomenon.Footnote 54

Logically, shisheh and the shisheh economy appealed particularly young people, who exploited the initial confusion and lack of legislative norms. At the same time, while opium and heroin had largely remained ‘drugs for men’ (although increasing numbers of women were using them in the early 2000s), shisheh was very popular among women. For instance, the use of shisheh was often reported in beauty salons and hairdressers, allegedly because of its ‘slimming’ virtue. In similar fashion, its consumption was popular among sportsmen, both professional (e.g. football players and wrestlers) and traditional/folkloric (e.g. zurkhaneh).Footnote 55 Its consumption appealed to categories of people enchanted with an idea of life as an hedonistic enterprise often governed by the laws of social competition, something that differed ontologically and phenomenologically from Islamising principles.

Reports emerged also about the use of shisheh among students to boost academic performance. By making it easy to spend entire nights studying and reviewing, especially among those preparing for the tough university entry examination (konkur), shisheh had gained popularity in high schools and universities. The shrinking age of drug use, too, has been factual testimony of this trend.Footnote 56 In an editorial published in the state-run newspaper, a satirist announced that, in Iran, ‘the modern people have become post-modern. And this latter, we know, is industrial and poetical’ and he longed for ‘the old good days of the bangis [the hashish smoker]’.Footnote 57 Shisheh epitomised the entry into the post-modern world, an epochal, perhaps irreversible, anthropological mutation. In view of this changing pattern of drug (ab)use, the authorities realised, slowly and half-heartedly, that the policies in place with regard to treatment of injecting drug users – harm reduction as implemented up until then – had no effect on reducing the harm of shisheh. Harm reduction could not target the ‘crisis’ of shisheh, which unwrapped in a publicly visible and intergenerational manner different from previous drug crises. Its blend, in addition, with changing sexual mannerisms among the youth, aggravated the impotence of the state.Footnote 58

Sex, Sex Workers and HIV

With drug use growing more common among young people and adolescents, people acknowledged shisheh for its powerful sexually disinhibiting effects, which, in their confessions during my ethnographic fieldwork, ‘made sex [seks] more fun [ba hal] and good [khoob]’. Equally, the quest for sex with multiple partners sounded appealing to those using shisheh, engendering the preoccupation (when not the legal prosecution) of the state. With moral codes shifting rapidly and the age of marriage rising to 40 and 35 respectively for men and women, pre-marital unprotected sex became a de facto phenomenon.Footnote 59

The combination of sex and drugs resonated as a most critical duo to the ears of policymakers, one that made Iran look more like a land of counterculture than an Islamic republic. Yet, because premarital sex was deemed unlawful under the Islamic law, the issue of sex remained a much-contested and problematic field of intervention for the state. Despite the repeated calls of leading researchers, the state institutions seemed incapable, if not unprepared, to inform and to tackle the risk of pre-marital unprotected sex. This attitude accounted, in part, for the ten-fold increase in sexually transmitted diseases in the country during the post-reformist period.Footnote 60

Many believed that while harm reduction policies were capable of tackling the risk of an HIV epidemic caused by shared needles, these measures were not addressing the larger part of the population experiencing sexual intercourse outside marriage (or even within it), with multiple partners, and without any valuable education or information about sexually transmitted diseases. The director of the Health Office of the city of Tehran put it in this statement during a conference, ‘we are witnessing the increase in sexual behaviour among students and other young people; one day, the nadideh-ha [unseen people] of today will be argument of debate in future conferences’.Footnote 61 The rate of contagion was expected to increase significantly in the years ahead, a hypothesis that was indeed confirmed by later studies.

As for the risk of HIV epidemics emerging from Iran’s unseen, but growing population of female sex workers, the question was even more controversial. Sex workers, in the eye of the Islamic Republic, embodied the failure of a decadent society, one which the Islamic Revolution had eradicated in 1979, when the revolutionary government bulldozed the red-light districts of Tehran’s Shahr-e Nou to the ground and cleansed it – perhaps superficially – of prostitutes and street walkers.Footnote 62 Government officials had remained silent about the existence of this category, with the surprising exception of Ahmadinejad’s only female minister Marzieh Vahid-Dastjerdi. The Minister of Health and Medical Education broke the taboo publicly stating in front of a large crowd of (male) state officials, ‘every sex worker [tan forush, literally ‘body seller’] can infect five to ten people every year to AIDS’.Footnote 63 The breaking of the taboo was a part of the attempt to acknowledge those widespread behaviours that exist and that should be addressed with specific policies, instead of maintaining them in a state of denial.Footnote 64 The framing of the phenomenon rested upon the notion of ‘risk’, ‘emergency’ and crisis. The opening of drop-in centres for women was a step in this direction, albeit initially very contested by reactionary elements in government. In 2010, the number of these centres (for female users) increased to twelve, the move being justified by the higher risk which women posed to the general population: ‘a man who suffers from hepatitis or AIDS can infect five or six persons, while a woman who injects drugs and makes ends meet through prostitution may infect more persons’.Footnote 65

The government, however, remained unresponsive to this call. Mas‘ud Pezeshkian – former Minister of Health under the reformist government (2001–5) – commented that ‘until the profession [of sex worker] is unlawful and against the religious law [shar’] there should be no provision of help to these groups’.Footnote 66 The result of this contention was a lack of decision and coherence about the risk of an HIV epidemic. According to an official report, the majority of groups at risk of sexual contagion (e.g. sex workers, homeless drug users) were still out of reach of harm reduction services.Footnote 67 If drug users in prison embodied the main threat (or crisis) during the reformist period, the post-reformist era had been characterised by the subterfuge of commercial sex and unprotected sexual behaviour, with the incitement of stimulant drugs such as shisheh.

A study published by Iran’s National AIDS Committee within the Ministry of Health and Medical Studies – with the support of numerous international and national organisations – revealed that only a small percentage (20 per cent) of the population between fifteen and twenty-four years old could respond correctly to questions on modes of transmission, prevention methods and HIV.Footnote 68 The crisis of this era was propelled, one could say, through sex, but also based on a certain ignorance of safe sexual practices, because of unbroken moral taboos.Footnote 69

The Disease of the Psyche

The changing nature of drug (ab)use and sexual norms – in the light of what I referred to as the broad societal trends of the post-reformist years – rendered piecemeal and outdated the important policy reforms achieved under the reformist mandates. In fact, shisheh could not be addressed with the same kind of medical treatment used for heroin, opium and other narcotics. Treatment of shisheh ‘addiction’ required psychological and/or psychiatric intervention, with follow-up processes in order to guarantee the patient a stable process of recovery.Footnote 70 This implied a high cost and the provision of medical expertise in psychotherapy that was lacking, and already overloaded by the demand of the middle/upper classes. Besides, methadone use among drug (ab)users under treatment engendered a negative side effect in the guise of dysphoria and depression, which could only partially be solved through prescription of antidepressants. The recurrence to shisheh smoking among methadone users in treatment became manifest, ironically and paradoxically, as a side effect of methadone treatment and a strategy for chemical pleasure.Footnote 71

The mental hospitals were largely populated by drug (ab)users, the majority of whom with a history of ‘industrial drugs’ use, a general reference to shisheh.Footnote 72 The rise in referrals for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, suicidal depression and other serious mental health issues needed to be contextualised along these trends. Suicide, too, remained a problematic datum for the government as it revealed the scope of social distress and mental problems emerging publicly.Footnote 73 But the increase of shisheh use markedly brought the question of drugs into the public space, with narratives of violence, family disintegration, abuse and alienation becoming associated with it. Although drug scares have always circulated in Iran (as elsewhere), they have mostly regarded stories of decadence, overdose, and physical impairment. They rarely concerned schizoid and violent behaviour in the public. With shisheh, drug use itself became secondary, while the issue of concern became the presence of highly intoxicated people, with unpredictable behaviours, in the public space.Footnote 74 As a law enforcement agent in the city of Arak confessed, ‘the heroini shoots his dose and stays at his place, he nods and sleeps; these people, shishehi-ha [‘shisheh smokers’], instead, go crazy, they jump on a car and drive fast, like Need 4 Speed,Footnote 75 they do strange things [ajib-o gharib] in the streets, talk a lot, get excited for nothing, or they get paranoid and violent’.Footnote 76 With this picture in mind, it does not surprise that Iran has had the world’s highest rate of road accidents and bad driving habits.Footnote 77 The trend of road accidents became also an issue of concern to the public (and the state), in view of investigations revealing, for instance, that ‘20 per cent of trucks’ drivers are addicted’, or that ‘10 per cent of bus drivers smoke shisheh with risks of hallucination and panic’ while behind the wheel.Footnote 78 Stories emerged also about violent crimes being committed by people on shisheh, establishing a worrying association between this substance, violent crimes (often while in a paranoid state) and, ultimately, long-term depression and mental instability.Footnote 79 More than being a sign of a material increase in violence, these stories are telling about the framing of this new substance under the category of crisis and emergency.

At the same time, shisheh became a cure for depression and lack of energy, also overcoming the urban–rural divide. I had confirmation of this more than once during my time spent in a small village in central Iran between 2012 and 2015. The shepherd known to my family since his adolescence, one night arrived in his small room, prepared some tea and warmed up his sikh (short skewer) to smoke some opium residue (shireh) which he had diligently prepared in the preceding weeks. One of the workers from a nearby farm, a young man of around twenty, came in and after the usual cordial exchanges, sat down, took his small glass pipe and smoked one sut of shisheh.Footnote 80 After their dialogue about the drop in sheep meat price in the market, the shepherd asked for some advice, ‘you see, it has been a while I wanted to give up opium, because you know it’s hard, I have smoked for thirty years now, and I feel down, without energy [bi hal am] all the time. Do you think I should put this away [indicating the opium sikh] and instead try shisheh?’.Footnote 81

In this vignette, the use of shisheh represents a response to the search for adrenaline, libido and energy in the imaginatively sorrowful and melancholic timing of rural life. Many others, unlike my shepherd friend, had already turned to shisheh in the villages, whether because of its lower price, its higher purity or opium’s adulterated state.Footnote 82 The government invoked the help of the Village Councils – a state institution overseeing local administration – in an attempt to gain control over Iran’s vast and scattered villages, but with no tangible results, apart from sporadic anti-narcotics campaigns.Footnote 83 By the late 2000s, drug adulteration (especially opium) increased substantially, encouraging drug users to shift to less adulterated substances – for example, domestically produced shisheh – or to adopt polydrug use. This caused a spike in the number of drug-related deaths, up to 2012, due principally to rising impurity (Figure 6.3).Footnote 84 The cost of using traditional drugs like opium and heroin was becoming prohibitive and less rewarding in terms of pleasure. Inevitably, many shifted to shisheh.

Figure 6.3 Drug-Use-Related Deaths

Conclusions

The phenomenon of drug use intersected over this period with long-term transformations that had bubbled below the surface of the governmental rhetoric and imagery of the Islamic Republic. Changing patterns of drug consumption, hence, was not the simple, consequential effect of new drug imports and lucrative drug networks, although these played their role in facilitating the emergence of new drug cultures. From the late 2000s onwards, drugs affected, and were affected by, broader trends in society, such as changing sexual norms, consumption patterns, social imagination, economic setting and ethical values. This represented a fundamental ‘anthropological mutation’, for it changed the way individuals experienced their existences in society and shaped their relation to the surrounding world. By this time, new cultural, ethical values gained traction, relegating to the past the family-centric, publicly straight-laced way of being in the world. The pursuit of sensorial pleasure, personal recognition and aesthetic renewal became totalizing – and totalitarian – in more rooted and uncompromising ways than the clerical ideology preached by the ruling class in the Islamic Republic. Not the ideology of the clergy, but the driving force of post-modern consumerism was the totalitarian drive of social change. To this epochal moment, the state responded haphazardly and incongruently, mostly unaware or unconcerned of what this transformation signified and in what ways it manifested new societal conditions where the old politics and rhetoric had effect. Rather than attempting a reconfiguration of the new cultural, social and ethical situation, the political order coexisted with the coming of age of new subjectivities, without recognizing them effectively.

Drugs, and shisheh in particular, were a manifestation of the profound changes taking place over this period to which the state reacted with hesitation and through indirect means. This chapter focused on social, cultural and human (trans)formations from the mid 2000s onwards, with an especial attention to the rise of shisheh consumption and its contextual psychological, sexual and economic dimensions. The next two Chapters dwell on how the state countered this changing drug/addiction phenomenon. An emblem of the anthropological mutation in lifestyle, imagery, values and flow of time, shisheh contributed to the change in political paradigm with regard the public place. It also brought about a shift in drug (ab)use and in the governance of drug disorder. Shisheh, hence, is both cause and effect of these transformations.