It is now time to weave the themes of this book together into a unified account of the relationship between the rule of law and the ideal of equality. This chapter will not present new evidence (except insofar as the results from the computer simulation reported at the end count as such), but will focus on synthesis and extension. The goal is to generate relatively bold claims about how the rule of law works in the world – claims that, strictly speaking, go beyond what is fully substantiated by the evidence and analysis offered so far, but are suggested by them; that can be explored and tested by future researchers; and that, if true, can guide policy makers in making the world a more lawful and more equal place. (The next chapter draws out some preliminary empirical and policy implications of the account of this book.)

First, let us define an analytic ontology. This book thus far has made three kinds of claims about the rule of law: conceptual/normative, strategic, and empirical.

A conceptual/normative claim is about what the rule of law is – that is, about the necessary or sufficient criteria for it to be the case that a state satisfies (to some given degree) the rule of law. I combine conceptual and normative claims because, as the rule of law is supposed to be normatively valuable, to say that a state meets the classification criteria to satisfy the rule of law to some degree is also to say that the state is, ceteris paribus, more morally valuable than it otherwise would be to a similar degree. Claims about what follows from the rule of law can be redescribed as necessary conditions for the rule of law, and for that reason, fall into this category; for example, the claim that “the rule of law makes people more equal” (in the specified respects) entails that an improvement in equality is a necessary condition for the rule of law.

A strategic claim about the rule of law is about the behavioral incentives the rule of law tends to generate, and about the social facts that tend to generate incentives to behave in accordance with the normative prescriptions of the rule of law. For example, the claim that “the sorts of political and legal institutions that tend to enable states to establish the rule of law also tend to enable officials to credibly commit to punishing people for doing things they don’t like” (Chapter 4) is a strategic claim. The strategic claims ought to be compatible with the normative claims: if we claim that the rule of law instantiates some normative value, then we would be embarrassed if it also gave people in rule of law states an incentive to undermine that value.

Finally, an empirical claim is what we would expect one to be: a claim about what we tend to observe or expect to observe about the rule of law in real states. Strategic claims obviously generate testable empirical claims, but so do normative/conceptual claims: as I have argued elsewhere, our account of what the rule of law is ought to respond to the cases of the rule of law we observe in the real world.1 For the same reasons, empirical observations generate normative/conceptual claims, and also, of course, suggest strategic claims.

As a whole, this book has defended three key claims, which we may call “the equality claim,” “the institutional independence claim,” and “the coordination claim”; respectively, they are that the rule of law constitutes as well as promotes an important kind of equal status among the subjects of that law, and between ordinary subjects of law and those with official roles; that the rule of law is independent of particular kinds of formal institutions (which I have called “practices”), such as jury trials, written constitutions, nominally independent judiciaries, and the like; and that the rule of law both conceptually incorporates and practically requires widespread coordinated action to hold the powerful to account – requirements that are built into the concept of the rule of law and are both normatively valuable and practically useful for facilitating that coordination.

Thus, in Chapters 1 through 4, I argued for conceptual/normative reasons that the rule of law is about equality, commitment, and constraint of officials, and that it does not require any particular institutional form of achieving those ends. Chapters 5 through 7 drew out these claims empirically, by investigating Britain and Athens, both of which can be understood consistently with the egalitarian interpretation of the rule of law, and both of which lack many of the institutional structures with which, in contemporary discourse, we associate it.

Chapters 4 and 6 began the work of building strategic claims about the rule of law. In them, I argued that the rule of law is a general-purpose technology for coordinating to control the powerful, and that the rule of law can be established and maintained in a community if there is a widespread commitment to it among those of the population with enough (political, military, economic) power to uphold the law.2 In this chapter, I will begin by drawing out that thesis about commitment to show that this suggests strategic defenses of the key claims. The rule of law should tend to be more sustainable over the long term when the law is more equal, which is to say (equivalently) that the weak version of the rule of law and less general versions of the strong version are less stable than strong instantiations of generality. Moreover, what matters is commitment, and that commitment is achievable when law is equal under a wide array of concrete political and legal institutions.

Next, this chapter examines the implications of those strategic claims for the relationship between the rule of law and democracy. Finally, it subjects them to the scrutiny of a complex computer simulation, to confirm that the strategic intuitions play out iteratively as expected.

I The rule of law’s teleology of equality?

Commitment is a double-edged sword. Because citizens cannot abandon the legal system when the law they have proves inconvenient without undermining their ability to rely on one another for coordinated enforcement when the law serves their interests (Chapter 6), law that is against the interests of a given group of citizens can persist through their own collective enforcement, at least to the extent that the legal system as a whole is sufficiently congruent with their interests that they will be willing to enforce it.

This is not all bad. Under some plausible conditions, particularly, where preference intensities over particular laws vary between interest groups in the community, this dynamic supports political compromise: interest groups will be able to uphold the provisions that are most important to them and only slightly disliked by the rest of the citizen body, in exchange for similar concessions made by other groups. This, in turn, is how, as many scholars say, constitutionalism lowers the stakes of day-to-day politics:3 by entrenching such provisions, and hence insulating them from the political process, constitutionalism only together with the rule of law (i.e., only when such provisions are actually obeyed) can effectively take the most important issues to some members of the community off the table, and hence support the commitment of those with intense preferences to the political community.

This same dynamic also contributes to the way that the rule of law may undermine citizens’ liberty. This is an extension of the point about credible commitment in Chapter 4. An official who wants to externalize enforcement of her commands in order to credibly commit to having them obeyed has to find a source of power greater than those commands in order to insulate the enforcer from the costs of enforcement. Louis might create as many de jure independent judges as he likes, but if he retains the practical power to command the judges to refrain from expensively enforcing his orders, the judges will not be independent in fact. Accordingly, in order for the rule of law to support credible commitment of officials, there again must be a critical mass in the community of those who have the will and enough power to insist that the law be obeyed over the short-term wishes of officials. But if there is, citizens may be complicit in the undermining of their own liberty.

Of course, there’s nothing surprising in this: even in Athens, we saw that the democrats necessarily restricted their liberty to ignore the amnesty in order to achieve their longer-term ends; one might debate whether this counts as a restriction on liberty as a whole.4 However, in nondemocratic contexts, where the law is more or less in the interests of the citizen body as a whole (or those who hold power within it), this can genuinely restrict their liberty, to the extent citizens have the ability to coordinate to uphold the law as it is but do not have the ability to coordinate to impose substantive legal change on the ruler (i.e., because of conflicting interests), but prefer living under a less-than-optimal legal system to a state without the rule of law. This is essentially Hobbes’s claim about the state of nature, but reframed in dynamic rather than static terms, and in terms of tyranny rather than anarchy: the members of a political community may offer continuing support to the institutions (like independent judges) that preserve their ruler’s laws, including those laws they don’t like, just in order to achieve the benefits of a legal order that is more or less compatible with their interests overall – and, in particular, to protect themselves from the hubris and terror that would come to them if the legal system collapsed without the collapse of the ruler, such that they could no longer collectively resist illegal force from that ruler. This is also the implicit bargain of the Magna Carta: by constraining the Crown’s use of force to law, those who rebelled also built the groundwork for institutions facilitating royal attempts to regulate them by law.5

There is an internal limitation on this mode of restricting liberty, however: the rule of law has to be basically in the interests of those who are called upon to enforce it. Obviously, the nobility in 1215 would not have wanted to hold the Crown to the law if the law were radically against their interests: the law can be so bad that the relevant public prefers the unbounded but inefficient and ineffective depredations of a ruler, where those depredations are limited by the inability to credibly commit to costly enforcement, to the efficient and effective enforcement of a tyrannical law.

Note: “the nobility.” Those who are called upon to enforce the rule of law need not be the masses – it might be that, for example, an elite, a bourgeoisie, or a nobility can call upon sufficient power to constrain top-level rulers and intermediate officials to respect the rule of law with respect to themselves, even as those below them in the hierarchy are ruthlessly oppressed. Before the abolition of slavery, continuing (albeit less so) through Jim Crow, and to some extent still today (as will be discussed in the Conclusion to this volume), the same can be said about race in the United States: the rule of law for whites only. Similarly, in Athens, in order for the rule of law to be sustained, the law had to be general with respect to citizen males, because citizen males had the power (ultimately, the wealth, arms, and coordination capacity) to force elites and magistrates to comply with the law. Women, slaves, and metics were not needed to enforce the law, and did not have the power to insist on legal rights for themselves. Thus, Athenian success in maintaining regularity and publicity went along with equal legal rights for the lowest socioeconomic citizen classes, but not women, metics, or slaves.

We can see this as a (limited) teleology of equality. Law that is not minimally consistent with the interests of those who are needed to enforce it against the powerful is unlikely to survive, because those people will have little incentive to enforce it. This suggests that we should expect to observe a greater incidence of law that treats them as equals at least to the limited extent of not disregarding their interests altogether, particularly in states whose legal systems have been stable for an extended period of time.

This is an empirically tractable functionalist account of the distribution of legal rights in states with constrained officials and elites, but one that does not depend on any kind of conscious pursuit of the rule of law. It so happened that Athens managed to maintain the rule of law, because the law was such that it was in the interests of the great mass of male citizens to uphold it. Had it not been in their interests, it would have been much less likely to have been successfully maintained. But that is not to say that equal law was enacted in order to recruit their support for the rule of law – it might be that equal law was enacted for any number of other reasons, including, inter alia, as a response to the need for expanded military participation, as a consequence of the increasing dispersal of wealth in a commercial society, or simply by revolutionary action. I do not propose to give an account of how societies achieve generality in this chapter, just how, if societies manage to do so, it helps them maintain regularity and publicity.

Because the scope of necessary generality depends on the distribution of power within a state, we should see more law that takes into consideration the interests of the most powerful (where how powerful one is tracks both one’s ability to sanction officials and what one might expect to get from the resources one controls in the absence of a functioning rule of law, and hence how cheap it is to abandon support for the legal system); truly general legal systems will be advantageous only in societies in which the dispersion of power is general. But this shouldn’t be surprising. The egalitarian advantage of the rule of law is not that it helps the powerless classes of society defy political reality, but that it allows classes with dispersed power to more easily coordinate to defend that power – it helps preserve preexisting mass power, but does not create it ex nihilo.

Moreover, the claim that nongeneral rule of law states are less stable does not come with a discrete time limit on it. A state might hobble on for centuries with radically nongeneral law if those who have the power to constrain rulers are never actually called upon to do so. This might happen if, for example, a state is ruled by an Olson-esque stationary bandit,6 who is rational and does not heavily discount the future, and hence voluntarily sets out a system of prospective law and complies with it, and sees to it that subordinate officials comply with it, in order to maximize the ruler benefits from stable and prospective law, such as improved economic productivity, leading to more extractable rents. Ordinarily, a ruler who wants more rents must create alternate sources of power that can actually constrain her to resist the temptation to break her own rules. But suppose the temptation never arises. Then such laws might be on the whole disadvantageous to those with the power to constrain the ruler, such that if the ruler chooses to disregard the law, those people won’t do anything to stop her, and the rule of law fails – but the ruler may never choose to disregard the law.

Looking at such a state one way, it lacks even the weak version of the rule of law: recall that the principle of regularity requires that officials be constrained, and here, the ruler is not constrained: she can abandon the rule of law any time she wants. However, we can also understand the state to satisfy the rule of law, at least partially, by virtue of the fact that subordinate officials are constrained; they’re just constrained by other officials: namely, the top-level officials in the form of the ruler or ruling coalition. And these subordinate officials are constrained for exactly the same reason that all officials, including rulers, are constrained in more just rule of law states: namely, in view of the fact that the legal system as a whole is in the interest of the one(s) doing the constraining. It just so happens that the one doing the constraining here is the ruler.

This strategic intuition leads to others about when the rule of law can be expected to fail. Two kinds of exogenous shocks can undermine a system of collective enforcement. First, the group of people needed to enforce the rule of law might change (call this a power-shifting shock). For example, political, economic, and/or military power might shift from a hereditary aristocracy to a nouveau bourgeoisie. Officials who perceive this might ignore the law, in view of the fact that the aristocracy no longer has the power to enforce it, and the bourgeoisie have no interest in doing so. The end result of this kind of shock might be a dictatorship; a revolution by the bourgeoisie, who impose a new legal system that is more consistent with their interests; or a quiet preemptive updating of the legal system to accommodate the interests of the bourgeoisie – where selection between these results depends on other factors, like the extent to which the bourgeoisie have the power to act collectively.

Another power-shifting shock is a raw expansion in the set of people necessary to enforce the law. When rulers or other officials become more powerful – more able to inflict sanctions, and to resist sanctions inflicted on them – relative to the group of nonofficials that previously upheld the law, this may actually create pressure for greater generality (or dictatorship) in view of the fact that midlevel elites no longer have the power alone to resist them. This may happen, for example, where social, economic, or technological change facilitates the centralization of power, where rulers acquire new resources to make side payments (bribes) undermining coalitions within the population (as may be one of the causes of the infamous resource curse7), or when foreign hegemons prop up rulers for their own purposes (as happened all over the world during the Cold War).

Thus, imagine a feudal state that is more or less consistent with the rule of law with respect to midlevel nobility, in view of the fact that those nobles control the military force on which the king depends.8 A bourgeois class exists, but because the landed nobles are powerful enough to enforce the monarch’s compliance with the law on their own, and the bourgeois are not sufficiently powerful to generate a demand for law that takes their interests into account or to resist either crown or nobles, the law is general only with respect to the nobility. Now the monarch develops the administrative technology necessary to centralize military power; all of a sudden, the nobles do not have the power to resist her alone. The rule of law with respect to nobles only has become unstable. Should the monarch start violating it (and she might not), it might tip into a more general rule of law if the nobles are capable of recruiting the bourgeoisie to backstop their coordinated resistance to her (and if their combined forces are sufficiently powerful to do so), or it might tip into dictatorship if they are not.9

Still another kind of exogenous shock: the law might cease to be in the (perceived) interests of those who had previously coordinated to enforce it, whether because of changes in the law or changes in circumstances. A state facing an existential threat, for example, may throw out the rule of law because, based on the discount rate of those who are to enforce it, the net present value of the rule of law is less than that of taking lawless actions to, for example, squelch internal opposition. This is part of the story of Athens, in which the people, terrified by short-term oligarchic threats in the context of the war with Sparta, (mistakenly) saw the danger of conspiracies represented by the mutilation of the Herms and profanation of the Mysteries as greater than the danger of losing the legal system. This is also at least arguably part of the story of the contemporary American response to the acts of September 11, 2001, including the Patriot Act, no-fly lists, extrajudicial detentions and assassinations, and the like.

Because of all these potential sources of shocks, I claim that the rule of law’s teleology of equality will have an expansive trend to it (albeit over time horizons that have the potential to be very long). All else being equal, where group A is a proper subset of group B, and assuming groups A and B are equally costly to coordinate, group B will have the capacity to resist those who would undermine its legal entitlements under a strictly broader set of strategic circumstances than group A. Ergo, in an environment characterized by shocks to legal system stability, we would expect law in the interest of broader groups of people to persist longer than law in the interest of narrower groups.

Of course, in ordinary coordination problems, groups A and B will not be equally costly to coordinate. However, law and collective trust are technologies of coordination that, by supplying a common set of norms and a common set of beliefs, are likely to reduce the coordination costs of larger groups once free-rider problems are eliminated, as in Chapter 6. We would still expect coordination to be less likely in large groups than in small groups, simply because at least some of the benefits of law are fixed-sum, such that the smaller groups would have more individual incentives based on capturing a larger share of the benefits.10 Nonetheless, because some legal rules are essentially indivisible (I suffer no direct loss to my immunity from being arbitrarily beaten by the police if my neighbor gains the same), legal rules should trend in a more egalitarian direction than other kinds of goods that political states distribute. We ought to observe, for example, minimally egalitarian law more frequently than we observe egalitarian distribution of wealth.

There is also a potential trade-off with respect to preference intensity – that is, between the extent to which all in the community view the law as a little in their interests, as opposed to some viewing the law as greatly in their interests. Suppose a state may choose between a more or less egalitarian legal system that all, or almost all, subjects perceive as better than anarchy or dictatorship, and a hierarchical legal system in which the elites extract resources from the lower class, thus providing truly massive benefits to the elites. And suppose both possible legal systems are stable in the sense that the elites, as well as the citizen body as a whole, have the capacity to coordinate to defend the legal system. Against some shocks, the hierarchical legal system may be more robust: if a shock to the egalitarian system makes it just a little bit less in the perceived short-term interests of all, it might fall, because citizens don’t care about it that much; a shock of similar magnitude to the hierarchical system might not damage the commitment of elites to defend it, because it provides them such great benefits that they will continue to see it as to their advantage even under slightly inferior conditions. However, this trade-off only goes so far: if a sufficiently strong shock arises such that the elites no longer have the power to defend their hierarchical legal system, all the preference intensity in the world will not save it.

What this all suggests is that the rule of law has a teleology of equality in a very limited, ceteris paribus kind of sense. However, a limited ceteris paribus kind of sense is still worth exploring, and can ground empirical predictions, like this one: legal systems that satisfy the strong version of the rule of law – in the limited sense of being minimally compatible with the interests of a larger share of the population – will be more robust against power-shifting shocks; for that reason, we should observe them more often than we observe legal systems that satisfy the weak but not the strong version of the rule of law, especially in states that have had stable legal orders for an extended period of time.

This provides all of the basics of an evolutionary account of the rule of law: a source of variation (the day-to-day struggles of politics and the diversity of social, economic, and military interests within and across states, leading to a wide variety of legal systems in the world); a source of replication (the year-to-year continuation of a legal system within a particular state); and a source of selection (the risk of exogenous shocks undermining less stable legal systems).11 We can rephrase the claim and prediction of this section in evolutionary terms: the claim is that the compatibility of a legal system, as a whole, with the interests of more people is an advantageous trait, and the prediction is that we should see that trait grow within the population of legal systems over a sufficiently long time. Thus, the teleology of equality.12

But the point is not yet complete. This section has argued that the weak version of the rule of law, standing on its own, is unstable – that the rule of law will be more likely to persist in a state if the law in that state is general in the sense that it is compatible, as a whole, with the interests of more of the subject population. But that isn’t the same generality that was elucidated in Chapters 2 and 3: generality in the sense that matters requires the law to be publicly in the interest of all in the community, in that it expresses their equality (or at least does not express their inferiority). This is a more demanding standard: ordinarily, a legal system that is worse for some members of the community than anarchy or tyranny will express disregard for those people as inferiors, since it totally disregards their interests, but not all legal systems that are better than anarchy or tyranny will be consistent with the equal status of all. The lower classes sometimes might be motivated to defend legal systems that treat them unjustly, just because the alternatives are so much worse. However, I now turn to a defense of the claim that it is real generality, not just Hobbesian better-than-anarchy for all, that is the teleology of the rule of law.

A Commitment, full generality, and the internal point of view

The most stable, commitment-worthy law is not merely coincidentally equal, or equal in the sense that it is more or less compatible with the interests of the class of people on whose commitment to the law the rule of law depends. Rather, the most stable law is publicly equal: it incorporates appeals to public reasons and thus is genuinely general.

In strategic terms, the reason for this turns on a problem of equilibrium selection. Chapter 6 showed that the rule of law can persist by collective enforcement in a society so long as enough of the people who are needed to enforce it think it’s in their overall interests. But there are other equilibriums as well (technically, an infinite number), including equilibriums in which collective enforcement never gets off the ground. And getting into a collective enforcement equilibrium requires some up-front investment: subjects must create the signaling mechanism that allows them to enforce the law against officials (except when Louis has done so, per Chapter 4), and they must trust one another in the first round (or for a significant period of time in order to develop a reliable pattern of collective enforcement). This investment will be worth making only if subjects actually have good reason in advance to think that the law is compatible with the interests of others.

One way this might happen is if the state is a genuine democracy, in which those whose support is necessary to uphold the law are also those who are counted as citizens and the democratic institutions work properly (are not captured or corrupted, etc.). Thus, it may have been easier for the Athenians to initially build support for their legal system, and restore it after the oligarchies, just because the democratic laws were known to be in the interests of the masses.

Toward the end of this chapter, I will explore this connection between democracy and the rule of law in more detail. However, recall from Chapter 4 the argument that rulers have incentives to institute (the weak version of) the rule of law in nondemocratic states. In view of the claim (defended in Chapter 1) that the rule of law does not conceptually require democracy, as well as the claim that nondemocratic rulers have reason to institute it, we should not be surprised if we observe that not all (weak-version) rule of law states are democracies.13 Also, of course, not all democracies function properly. Moreover, even in a well-functioning democracy, social choice theorists have shown that aggregative methods can fail to produce results preferred by the populace.14 Citizens who know this may have good reason to suspect that not everyone sees even democratically enacted laws as consistent with their basic interests. Hence, in order to get into the rule of law equilibrium of Chapter 6 (other than by dumb luck), they need some way to come to an initial belief that the laws are in the interests of their fellows.

One way to achieve this, both in democracies and in nondemocracies, is for the law to be publicly justified or justifiable by reference to a legitimate conception of the collective good or the individual interests of all in society. If the legal system as a whole visibly takes the interests of all into account, that gives each in the community some substantial reason to think that it will be more or less compatible with the interests of her fellows; if it visibly disregards the interests or equal status of some people, that gives those in the community very strong reason to suppose that those whom it disregards will not be able to see it as in their interests. These evaluations will, in turn, influence whether it is rational for them to make the initial investments necessary to build trust in a legal system.

The foregoing discussion indicates the importance, at least at the beginning of a legal system, of laws that are truly general. But their importance does not end there. The extent to which subjects perceive the law to be in their interest is not a mere calculation of hedonistic self-interest. Someone who is insulted by the law, who is treated as a second-class citizen, can come to reject the legal system that allows such insults even if, as a whole, it nonetheless overall protects the person’s basic interests and is better than the likely alternatives. Consider, for example, the way that the revolutionary wing of the civil rights movement, such as Malcolm X and the Black Panthers, stood in opposition to the legal system, rejecting its benefits and proposing radical resistance to it.15 From a 1963 speech by Malcolm X:

Jesus two thousand years ago looked down the wheel of time and saw your and my plight here today and he knew the tricky high court, Supreme Court, desegregation decisions would only lull you into a deeper sleep, and the tricky promises of the hypocritical politicians on civil rights legislation would only be designed to advance you and me from ancient slavery to modern slavery.16

Those are the words of an activist who has been driven by profoundly unequal treatment to abandon the law and reject even the progress and benefits offered by the legal system. And who could blame him? Yet it’s unlikely that the revolutionary wing would have ever had a realistic chance to win the war some of their members hoped to spark, or would have prospered in the collapse of the legal system (if nothing else, white racists had the advantage of numbers). And it’s implausible to think that the members of the revolutionary wing of the civil rights movement saw themselves as foils for the more peaceful side (even if some might have, and even if after the fact we can see that Malcolm was instrumental in the success of Martin). The revolutionary wing of the civil rights movement cannot be understood as rational without supposing that their members did not pursue self-interest in the narrow sense, but acted in accordance with their righteous rage against a legal (and social, and political) system that expressed their inferiority.

The same motivations can help us understand the 1992 Los Angeles riots, following the acquittal of the police who savagely beat Rodney King. The refusal of jurors to convict the police for beating a black man must have led at least some of the rioters to, however temporarily, cast aside their regard for the law, even though it’s hard to understand a narrowly self-interested motivation for rioting under such circumstances, and there is no obvious reason to think that they were playing their role in a Chapter 6-style coordinated sanctioning equilibrium that ordinarily kept the police in line. Rather, we should understand the riots as a response to expressive, not pragmatic, motivations: at least some of the rioters felt that the legal system treated them with contempt, and so cast aside their allegiance to it.

As I finalize a draft of this chapter at the end of April 2015, the country seems to have been flung back into the 1960s. Last fall, the police killing of a black man sparked riots in Ferguson, Missouri, and just last week, the killing of a black man in Baltimore, Maryland, has sparked riots that are occurring today. Ta-Nehisi Coates, a prominent black journalist who has become a major establishment-located voice of the African-American left, just captured the heart of the matter:

When nonviolence is preached as an attempt to evade the repercussions of political brutality, it betrays itself. When nonviolence begins halfway through the war with the aggressor calling time-out, it exposes itself as a ruse. When nonviolence is preached by the representatives of the state, while the state doles out heaps of violence to its citizens, it reveals itself to be a con. And none of this can mean that rioting or violence is “correct” or “wise” any more than a forest fire can be “correct” or “wise.” Wisdom isn’t the point, tonight. Disrespect is. In this case disrespect for the hollow law and failed order that so regularly disrespects the rioters themselves.17

Half a century apart, Coates and Malcolm X make the same point: when the law presents itself as “hollow” and “disrespects” those whom it is supposed to protect, the disrespected turn around and direct that disrespect right back at law. The physical manifestations of righteous anger in Ferguson and in Baltimore are poorly understood as some kind of calculating self-interest. Rather, they are evidence that people deeply value being publicly treated as equals by the legal system, and respond to that kind of equality – or to its absence – with action.

I will discuss the problems of racist policing in the United States at the close of this book. For now, let us imagine a more just society. Once we move beyond the narrow motivations of self-interest, we get into what H. L. A. Hart called the internal point of view.18 Subjects can accept or reject the law in view of its expressive characteristics for its own sake rather than for reasons of brute instrumental rationality. Subjects who take the internal point of view on the law because they think that it as a whole expresses their equal status in the community, and instantiates values that they respect, need not engage in a calculus of self-interest each time they are called upon to support the law against disobedient officials; rather, they do so reflexively, based on the importance of the law to a political community they value, and that values them. Under those circumstances, the problem of Chapter 6 dissolves: a community has a legal culture in which subjects trust one another implicitly to support the law, in virtue of their long-run relationship of mutual regard with it.

Accordingly, we should expect genuinely general law to be more robust to the kinds of shocks described in the previous section than law that is merely compatible with the interests of all, given their alternatives (which might be lousy). “You should defend this legal system, which puts me in a hierarchically superior position to you and allows me to treat you badly, because I’m (however slightly) less likely to kill you or take your stuff in that system than in a Hobbesian anarchy” is convincing for only so long.

Moreover, the rule of law’s teleology of equality may be more than a mere evolutionary claim. For it may be that the forms of law themselves create pressure to equality. Recall that in Chapter 3 I argued that the weak and the strong versions of the rule of law are rooted in the same abstract ideal, that of the demand that reasons be given for the use of power. As discussed in that chapter, others have seen this connection, prominently including the Levellers of the seventeenth century. Consequently, states that merely achieve the weak version of the rule of law may find their legal caste structure undermined by the persuasive power of the law to convince those within it – both those privileged participants in the system who take the internal point of view on it and those who are thrust into subordinate places in that system – that reasons must be given for the subordination of its lower-caste members. This is why Martin Luther King Jr. could decry Jim Crow, in the letter from the Birmingham jail, in terms of his respect for law.

E. P. Thompson (Reference Thompson1975, 263), perhaps the scholar with the greatest insight into the function of the rule of law, explained all of this first. He noted, “In the case of an ancient historical formation like the law, a discipline which requires years of exacting study to master, there will always be some men who actively believe in their own procedures and in the logic of justice.” In other words, carrying out the cognitive operation distinctively associated with (even unjust instantiations of) the weak version of the rule of law – the giving of reasons for the use of public power – has the potential to train participants to carry out that operation about the content of the laws themselves. This, in turn, has the potential to destabilize laws that are not justifiable by reasons that can be given to others.

II Commitment and institutions

Return, for a moment, to institutions. It’s often supposed that particular kinds of “institutions” – by which those who do the supposing tend to mean concrete political arrangements, most commonly independent courts, but others are raised as well – are necessary for, or even constitutive of, the rule of law.19 In Chapter 1, I disagreed, and offered that disagreement as a conceptual claim: the rule of law does not require, for example, judicial review, the separation of powers, or the jury trial. However, that claim might be subject to question on grounds of factual robustness: if, practically speaking, every stable rule of law state can be expected to have them for strategic reasons, then perhaps we ought to say that they’re part of the concept of the rule of law as well.

To the contrary, I claim that there are institutional prerequisites for the long-term sustainability of the rule of law, but those prerequisites are malleable and contingent. As I have been arguing, the key difference between a successful rule of law state and one that does not succeed is the extent to which the people whose coordinated resistance is necessary to hold officials and powerful elites to the law are committed to doing so; the key determinant of that commitment ought to be the extent to which the law publicly takes their interests into account – that is, treats them as equals.

If this is true, it suggests that any institutional prerequisites will depend on what the people in a given state happen to need to support their coordination, which will depend on that state’s history, distribution of power, existing level of trust, demographics, and other distinctive characteristics; moreover, multiple institutional arrangements may be sufficient to support coordination in a given state. In Athens, the mass jury was a powerful tool of coordination, because it allowed the citizen body to simultaneously signal their commitment to the rule of law (rebuilding the trust lost in the fifth century) and resolve legal disagreement. In the United States, with a longer tradition of reliable control of officials by law, such a signaling function is less urgent, and an elite judiciary does more or less fine in coordinating public opposition to illegal acts. In Britain, as described in Chapter 7, it has been supposed, plausibly, by scholars such as Dicey that the parliamentary system backstopped by constitutional custom is sufficient to leverage general acceptance of these constitutional norms into the constraint of the powerful.

Citizens who are committed to the rule of law will have a strong incentive to bring about the institutions that allow them to carry out their commitment. Thus, for example, we should expect that states whose citizens are committed to the law will create independent courts, juries, and the like, where none have previously existed.

Moreover, we should expect institutions like judicial independence and the jury trial to follow, not precede, a widespread commitment to law, for they presuppose such a commitment and something like a rudimentary version of regularity already existing in the community. To see this, consider the problem of ineffectual courts. A state might have judicial independence written in its constitution; it might be that judges are in fact independent from other officials, such that no official pressures judges to make any particular ruling. However, if that state does not satisfy the principle of regularity, there’s no reason to believe that officials will obey the rulings of the independent judges. The same goes for juries or any of the other institutions that are supposed to support the rule of law. To the extent those institutions are themselves legal institutions – that is, institutions whose functions are specified by law – they can be effective only if there is a preexisting commitment to enforce their legal role, to make sure the court or the jury is obeyed, and if that preexisting commitment is cashed out in some baseline level of coordinated community action.20

In short, to say that “the rule of law will exist when there are independent judges” is a tautology. There cannot be genuinely independent judges (where the concept of “judges” includes an actual function in successfully adjudicating legal disputes and having their rulings obeyed) unless there is already the rule of law.

Consider for a moment how this argument applies to the American case. It looks like the US Supreme Court is enforcing its judgments directly against officials. However, I have argued elsewhere that such enforcement is effective only to the extent there is widespread knowledge that its rulings are backed by the prospect of political or other sanctions from ordinary citizens, who are committed to the rule of law.21

On such an account, the Court functions like a signaling device: within some constraints, when elected officials break the law, it says so; it having said so, the elected officials cease their illegal conduct because, if they do not do so, the people (to the extent they are part of the bargain) will be able to coordinate to punish them at the polls or elsewhere. What the Court provides is information: it resolves uncertainty about whether elected officials have broken the law – or, to be more accurate, it resolves each individual citizen’s uncertainty about whether each other individual citizen will see the politicians as having broken the law, and thus allows them to depend on one another to punish the politicians in question, to the extent they trust one another to be committed to upholding the law. Because politicians know (or intuit) that the Court serves this function, they do not disobey it.

Suppose this account of how the US Supreme Court works is right. That explains why nobody had to visibly force politicians using sanctions to comply with Roe v. Wade: disobedience is off the equilibrium path. And with this conception of the role of a constitutional court in a stable rule of law state, we can see a number of features that are not required. First, such a court need not be composed of elite judges. A mass court such as the Athenian jury will do just fine. The court need not be independent of elections – many elected state judges in the United States also serve their signaling function just fine, and routinely strike down acts of other elected branches of government, or of the people themselves.22 Nor need it have the formal power to strike down legislation: courts operating under the “new commonwealth model,” which make nonbinding declarations of unconstitutionality, have been sometimes successful in motivating “voluntary” legislative action.23 The previous chapter gave the British antiterrorism example.

More strikingly, on this model, the “court” need not be a court at all, and need not even be in government. Any independent sender whose signals the people come to trust can be used. For example, in a country with no independent judges, a particularly virtuous (or seen to be virtuous) newspaper editor could, hypothetically, serve this role, if a consensus builds such that if the editor condemns a government policy as unconstitutional, the people will punish the politicians if it isn’t retracted. In principle, even decentralized information cascades – in which a few people signal that they see the government action as illegal, leading those who trust them to send such a signal themselves, and so forth – could do the trick, at least in a society in which the cost of sending such a signal is relatively low for the initial sender (i.e., not one in which dissidents are promptly shot).24

Nor need the court (or editorialist, or angry citizen) be enforcing a determinate written document. A consensus set of social norms will do; if those norms are accepted as a set of constraints on government and reliably enforced, there’s nothing (at least for a legal positivist) preventing us from counting them as constitutional law, and, in countries like the United Kingdom, we already do so. In principle, we need not even have that much. Suppose our newspaper editor is believed to be really virtuous, such that the public at large trusts the editor’s judgment about the appropriate constraints on official action; the public could just coordinate on that judgment without any preexisting law at all.

Of course, this can go only so far. Specific, preexisting, and public laws (written or otherwise) must exist to authorize direct official coercion over citizens, or the principles of regularity and publicity go out the window. But there’s no particular reason that additional side constraints on official power, beyond those required by the weak version of the rule of law, can’t be instantiated by the judgment of any old person. For example, our hypothetical virtuous newspaper editor might think that for particularly high taxes the legislature ought to have a supermajority; if the editor invalidates laws on that ground and the people successfully enforce it, nothing in the rule of law is offended. The point is that once we accept that independent judges work by sending a common knowledge signal of illegality that the public can coordinate around, we can see a variety of ways by which such signals can be sent. No particular method is necessary, and none will work absent public commitment.

That being said, institutions like judicial review will doubtless make it cheaper and easier to enforce the law against officials. Coordination is costly, and as the subgroups of the population of a state who must be coordinated become relatively mass rather than relatively elite (due to the rule of law’s teleology of equality), we can expect these costs to become more meaningful. Signal senders – like courts – that have the credibility of a public office, formal protections against retaliation (which themselves can be enforced by coordinated judgments), and the focal point advantage of being picked out as the designated signal senders by law can be expected to facilitate mass coordination more cheaply than, say, newspaper editors.

For this reason, we would expect to see more helper institutions like independent formal judiciaries in states where the law is more general. The logic of this empirical prediction is as follows: where the distribution of power in a state requires mass coordination rather than merely midlevel elite coordination to enforce the law against top-level officials and elites, we would expect the law to be more general; only in such states will the masses have the incentive to coordinate (the teleology of equality). In such states, we would also expect to see helper institutions, for with such institutions the masses will be more likely to have the ability to coordinate. However, this empirical correlation, if it exists, will not imply that the rule of law can be created merely by installing independent judiciaries, for the means without the incentive will not be used (and, as the next chapter will discuss, the institutions installed must be locally legitimate). Similarly, we should see more helper institutions in more populous states, and more of such institutions in more politically, religiously, and culturally diverse states where citizens cannot so easily guess one another’s views about the law.

All of this suggests that particular institutions, like independent judiciaries and judicial review, are good signs of the rule of law: they are more likely to exist in rule of law states, because in such states they may help preserve the rule of law, and the rule of law, in turn, is the precondition for their effective exercise of power. Hence, they can be used to proxy it in empirical measures. But they are imperfect proxies of the rule of law, and rule of law states can and have existed without them. In the next chapter, I discuss the implications of this idea for empirical measurement of the rule of law.

A Democracy and the rule of law

Mass coordination need not be the sole province of democracies. Consider the Ancien Régime parlements, which, in the buildup to the French Revolution, refused to enter a number of royal decrees, particularly relating to taxation, on the grounds that they were illegal; the royal response – exiling the parlements – led to copious public unrest that helped bring on the revolution.25 And as I have argued, the rule of law can (conceptually) exist in the absence of democracy.

Still, the teleology of equality gives us some reason to expect an empirical association between the rule of law and democracy, for two reasons. First, as noted, a state may build collective trust in the commitment of each citizen to contribute to collectively upholding the law by structuring its lawmaking process in such a way that the laws are maximally likely to be compatible with the basic interests of all; a democratic process may serve this function to the extent it disperses influence over the substantive content of the law more broadly than other legislative processes.26

Second, and more basically, one of the ways in which law can be general is that it provides for more general influence over the legislative process. While nondemocratic legislative processes can comply with the principle of generality in appropriate social contexts (for example, a devout religious community may locate legislative power in the clergy without thereby expressing the subordination of anyone else), such processes are less likely to be so compatible in heterogeneous communities. For that reason, democracy may not be necessary for the weak version of the rule of law, but, in most real-world societies, we ought to expect it to be necessary for full instantiations of the strong version.27

The relationship between the rule of law and democracy along the conceptual, strategic, and empirical dimensions is proving to be complex. Before exploring further, we must get clearer on this notion of “democracy.” It is probably an essentially contested concept, but any conception of democracy worthy of the name will be an evaluative standard for the relationship between the cognitions (wills, beliefs, desires, attitudes, intentions) of ordinary (nonelite) people and political outcomes. Most conventionally, democratic theorists suppose that there must be some intentional causal relationship between the latter and the former: for a state to be a democracy, people must be able to operate the levers of their political machinery to bring about political outcomes, and the political outcomes must be the products of those operations.

In other work (currently in progress), I am arguing against this view, and in its place I aim to construct a heterodox view about the relationship between democracy, popular sovereignty, and after-the-fact endorsement; I cannot defend it here. (Also, the view may turn out to be indefensible.) For present purposes, it will do to distinguish between two democratic ideas: a demanding agency idea, according to which the masses of ordinary people have to have substantial effective control (in one way or another) over political outcomes, and a less demanding approval idea, according to which the masses of ordinary people have to be able to approve of the sort of political outcomes that their system tends to generate. We can designate systems that comply with each conception as agency-democracies and approval-democracies, respectively. As I have not yet given an account of approval-democracies, and agency-democracies represent the conventional view, I will limit the discussion here to the latter only.28

The weak version of the rule of law is likely to be strongly correlated with agency-democracies (if not, strictly speaking, required for it). If the masses are to exercise genuine control over political outcomes, they are likely to need sophisticated coordination tools in order to overcome the natural monopolies of political states – hierarchical control over military force, concentrated wealth, and the like – and reliably hold on to authority. For the reasons described in Chapter 6, public law is just such a tool. Moreover, if they use law as a coordination tool, then that law must actually exercise effective control over officials in order for the state to be properly characterized as a democracy. Otherwise, the agency conception necessarily cannot be satisfied: the people are trying to direct their political outcomes by writing these things called “laws,” but the political outcomes, given by the actions of officials using the tools of the state, are not tracking those efforts.

Moreover, not only is the rule of law likely to facilitate democratic control over political outcomes, but the institutions that facilitate democratic control over political outcomes are, for the reasons given in Chapter 6, more likely to facilitate the rule of law. Consistent with this hypothesis, Law and Versteeg have found, based on a worldwide data set, that democracy (proxied by polity scores) is a better predictor of states complying with constitutional rights than whether judicial review is included in a state’s constitution.29 This is to be expected, once we consider that more democratic states are open to more popular participation in all kinds of institutions for governing the powerful, and hence are more likely to be able to generate consistent signals of public support for the law.

However, in a very homogeneous democracy, the mass might rule without the aid of law. Recall that this characterizes many classicists’ accounts of Athens, such as that of Adriaan Lanni: the people controlled political outcomes by coordinating to enforce customs and norms, not (prospective, reliably enforced, etc.) laws, through their political and legal institutions. In Chapter 5, I argued that we can understand as law those norms that Lanni identified, and in that way understand Athens as a rule of law state.

But suppose I am wrong. Maybe Athens was a “tyrannical democracy” that controlled the open threats represented by the wealthy by generating its own against them; those who complained of sycophants who abused the jury system in order to expropriate the wealthy alleged just such a tyranny. In essence, the accusation was that the masses collectively maintained the political authority of their democracy through terror. Suppose (contrary to what I argued in Chapter 5) that they were right: the possibility by empirical example of a democracy without the rule of law will have been established – but an example will have also been given of its instability, for it was the failure of democratic legal self-control that contributed, I argued in Chapter 6, to the fifth-century collapse and taught the demos to recommit to the rule of law in order to take fratricidal conflict between mass and elite off the political table.

As a whole, it seems as though we do best to understand democracy as most compatible with intermediate to advanced stages of the development of the rule of law: if it is possible in the absence of the weak version of the rule of law, the combination is strategically plausible only in relatively homogeneous societies in which the masses can act without sophisticated coordination tools; even in such societies it may not be stable. Once they exist in relatively rudimentary versions, democracy and the strong version of the rule of law can be expected to grow together, for they refer to the same fundamental idea of a state that is publicly compatible with the legitimate interests of all, and thereby expresses the equality of all.30

III Diversity, generality, and democracy

Because of its relative homogeneity, Athens is in part a poor model for modern rule of law democracies. Modern mass democracies tend to be characterized by varying degrees of religious, ethnic, cultural, and other forms of diversity, leading to groups who may experience their interests as distinct. At the same time, these democracies may also be characterized by distinct social and economic elites (who may or may not be dispersed among demographically dissimilar groups) who may have disparate power. Athens, by contrast, is often understood as having been much more homogeneous, and though the standard one-dimensional division into mass and elite is distorting and reductive, it is close enough that it helps us understand quite a lot about what actually happened.

A population may be demographically diverse in at least three relevant respects, which may combine. First, it may have a higher degree of dissimilarity, in that there are more different kinds of people (for some meaningful conception of “kind-ness”) in the population, independent of the quantity of people in each demographic classification. Second, the population may be dispersed more evenly among those different kinds of people (i.e., a population with half its members in one group and half in another group is more diverse, in this sense, than a population with 90 percent of its members in one group and 10 percent in the other). Third, relevant kinds of power (particularly, for present purposes, the power to sanction officials and others with concentrated power) may be dispersed more evenly among those different kinds of people.

These divisions are relevant for the maintenance of generality as well as democracy. Even modeling, as we have been, a modern state as a small group of very powerful elites and a large mass that must act in concert in order to keep the elites in place, diversity among that mass may impair its ability to coordinate. For example, the divide-and-conquer tools of elites may be deployed to ally with some portions of the nonelite, undermining the capacity of the latter to coordinate.31

The dynamics of legal stability in the face of the interaction of those three types of diversity has the potential to be highly complex, especially when population and power come apart; we might not observe the same macro-level consequences in states with, for example, few groups and dispersed power versus many groups and concentrated power, and it is hard to see how purely analytic predictions can be made. Accordingly, in order to extend the strategic ideas previously developed about homogeneous rule of law states (and rule of law democracies) in this chapter and in Chapter 6 to more complex diverse states, we can lay down both this chapter’s strategic intuition development and Chapter 6’s game theory and pick up computer modeling instead.

IV Simulating legal stability

I have programmed a computer simulation to further explore the strategic dynamics of rule of law states. The goal of the simulation is to iterate and flesh out the strategic intuitions given by the claims above: assuming that the micro-level intuitions are right, what follows on the macro scale?32 Thus, this simulation makes rough mathematical representations of micro-level claims like “People are more likely to resist officials when they trust that others will do so as well” and “Elites and officials might attempt to bribe people to undermine their participation in collective coordination mechanisms to resist the law,” and then iterates those representations over a large number of interactions, and for a very large number of randomly set starting conditions, such as (mathematical representations of) the extent of preexisting legal equality, the distribution of power and heterogeneity of social groups, and the initial level of trust present in a society.33

A computational model allows high levels of complexity to be analyzed, in order to generate insights that may be unattainable through purely analytic methods and unavailable to direct real-world observation, though at the cost of sensitivity to initial modeling choices. It also allows exogenous shocks to be introduced, in the form of round-by-round stochastic variance applied to model parameters. What follows is not, however, the same as what researchers in social science usually describe as an “agent-based model.” An agent-based model typically involves networked agents who interact with one another, often with very simple decision rules (to aid interpretability) and with emergent complex systemic outcomes.34 By contrast, the model described next features agents with fairly complex and often stochastic decision rules, reflecting the multitude of cross-cutting incentives facing actors at the inflection points of a legal system, but with relatively minimal interaction patterns. The model is written in the R statistical programming language, and the full code is available online.35

The population consists of 1,000 ordinary citizens and 100 elites, where an elite represents a powerful government official or a wealthy and high-status private citizen. There is also a distribution of 10,000 units of (legal) goods across mass and elite, where these distributions represent the benefits to be had from law that is consistent with one’s interests (maximally general law is represented by an identical allocation of goods to each citizen). There is also a distribution of 10,000 units of power across mass and elite, where each unit represents the ability to influence the outcome of a conflict in the event the elite attempt to break free from the power of coordinated sanctions.

In each round, elites determine whether or not to (a) allocate all of the goods to themselves; (b) offer some bribe (as a portion of the legal goods) to some portion of the mass group (defined by subgroups, which are assigned randomly; the elite may bribe subgroups only in their entirety) and then allocate all of the rest of the goods to themselves; or (c) retain the status quo. The elite group makes this decision by searching over the space of choices (including the space of possible bribes) and then choosing the option that maximizes the individual elite expected utility function EUe = (1 – πμ – σπΣ(ρj/γj))αe, where μ ∈ [0,1] represents the share of the power held by all mass subgroups that have not been bribed; αe represents the total amount the elites allocate to themselves/100 (i.e., the amount of legal goods to be controlled by a single member of the elite under the given bribe); γj represents the amount the elites have spent to bribe group j, and ρ represents the total power of the members of group j, where j indexes all groups that have received a bribe. Much of this is meant to capture the notion that even bribed people may resist usurpation, depending on the degree of commitment and the amount they have been bribed, but at lower probability than unbribed people.36 Π ∈ [0,1] is the trust parameter, representing the degree of trust among the mass in the collective commitment to resist usurpation, which captures the baseline expectation about the proportion of the population who are likely to resist a power grab; π is an observation of Π with some error, such that π = Π + ε; ε ~ N(0,β); β ∈ (0.01,0.8). (values of π not in [0,1] are constrained to the end points). Similarly, σ is an estimate of an unobserved general commitment parameter Z ∈ [0,1], which represents the extent to which members of the public will resist even profitable bribes because of their long-term commitment to the system; the estimate σ is constructed in an identical fashion as is π. Where the elite choose to retain the status quo, π is constrained to be 0. Accordingly, the expression (πμ + σπΣρj/γj) represents the subjective probability a member of the elite has in being overthrown.

If the elites decide to attempt to take all the goods for themselves or bribe some subgroup and take the rest, each member of the masses decides whether to reject any bribe and revolt or to acquiesce and take any offered bribe, by choosing the larger of the expected utility functions (ties go to resistance) EUi,revolt = αi – (1 – θiμ – σiθiΣ(ρj/γj))ψ, EUi,acquiesce = (1 – Zi)(δj/γj) where α is the initial distribution of goods to that individual; δj represents the amount of the bribe, if any, to that individual’s subgroup; γj represents the number of members of this subgroup, ψ = Ueταm; that is, it represents the penalty for attempting to resist and losing, which is the product of the mean amount of legal goods allocated to members of the mass αm, the proportion of power held by the elite Ue, and a random penalty parameter τ ∈ [0.5,5]. Zi is the individual’s personal commitment parameter, which tracks the extent to which the person is willing to sacrifice individual short-term self-interest to preserve the legal system; θi represents that individual’s estimate of the trust parameter Π, calculated in the same way as π, but on an individual-by-individual basis (i.e., with individual error), likewise σi. All other variables represent the same as they represented in the elite expected utility function. The individual commitment parameter is determined by the extent to which the citizen is treated fairly relative to other members of the mass by the distribution of legal goods, the citizen’s perception of the extent of trust in the community, and the overall level of commitment in the community, such that Zi = (Z + θi(αi – λ))/2, Zi ≤ 1. Here, λ represents the average share of the goods allocated to the mass under the status quo distribution, that is, the total mass share divided by 1,000, and the expression αi – λ is constrained to be nonnegative. The expression 1 – θiμ – σiθiΣ(ρj/γj), ∈ [0,1] represents citizen i’s subjective probability of losing a revolt.

The starting parameters of the model are an initial distribution of goods,37 a distribution of power,38 a number of subgroups within the masses (n ∈ [2,5]), a distribution of those subgroup identifiers among the mass,39 an initial trust parameter value Π ∈ [0.1, 0.9], a general commitment parameter Z, a value for the trust and commitment estimation error variance β, the penalty parameter τ, a distrust decay term Δ of either 0 or. 01, and a shock variance parameter κ ∈ [0.05, 0.9] to be described later. One simulation run consists of a random assignment of each initial parameter from a uniform distribution over their possible ranges, and repeats for 1,000 rounds or until the elites successfully change the distribution of legal goods in their favor (i.e., they overcome the potential of coordinated resistance); the output of each simulation is a description of the original parameters plus the number of rounds it took for the elite group to steal some or all of the goods.

Each round after the first experiences a shock to the distribution of power: from the set of subgroups of the mass plus the elite, two groups are randomly chosen from a uniform distribution, and then a proportion φ of the power from the first is transferred to the second (taken equally from each member of the former and distributed equally to each member of the latter), where φ ~ N(0, κ). In each round in which the elites attempt to loot, the masses successfully resist them with probability Σi=1…k μi, where (1 … k) are the members of the mass who resist – that is, with probability equal to their aggregate share of the total power. If the elites win, the run immediately ends. If they lose, Π changes to equal the proportion of the mass who resisted the takeover attempt, and the run continues with a new round.40 If they do not attempt to loot, Π increases by ΔΠ (up to a limit of 1) and the run continues with a new round.

One final concern motivates the addition of some additional complexity to the model. The power of a group is to some extent endogenous to the legal rights of that group, for groups that are deprived of legal rights may become deprived of power as a result. We see a contemporary example of this in the condition of African-Americans in the United States: racially disparate policing (which in the model is captured by a relative lack of legal goods) leads to mass incarceration, and thus both to reduced economic power in the African-American community and to reduced political power (especially through felony disenfranchisement laws). It may be that this dynamic makes unequal legal systems more stable than they otherwise would be, because groups that are the subject of severe inequality over time become less important for the preservation of the legal order. In order to model this effect, a power decay parameter χ ∈ [0,0.5] is randomly assigned at the start of each run. Each round, before shocks are applied, each member of any group whose mean goods endowment is more than 1.5 standard deviations below the mean groupwise goods endowment among the mass suffers a decay equal to χ multiplied by the individual’s power. This will allow us to test the effect of any such disempowerment tendency.

Even this complicated model simplifies important calculations. Most serious is that players consider only current-round payoffs. Based on the parameters in play, it is impossible to generate a convincing account of how players will estimate future-round payoffs. In principle, we could do so for modeling purposes by calculating, for each round, discounted expected payoffs for every future round based on given assumptions about, for example, the prospects for a successful countercoup if the elites take over. However, doing so would not only drastically complicate even the programming of the computer simulation for this model, but would also impose unrealistic assumptions about the extent to which human beings can or ever would form meaningful expectations about such things. I suggest that the existing simulation actually better models the likely real-world human decision-making process in a situation of dire political conflict, constitutional crisis, or even civil war, when short-term outcomes are likely to be extremely salient and discounting is likely to be very high (not least because in many such situations death is a realistic prospect).

Other parameters are constrained for the purpose of simplification. The ratio of elite to mass is fixed; however, this is unimportant, because the strategically important information that ratio might provide is the difference in the distribution of power and goods between mass and elite; rather than vary the populations, those underlying distributions themselves are allowed to vary. More important, it is assumed that elites act in unison; this simplifies away an entire body of literature about intra-elite competition (although some of this is indirectly captured by the round-by-round shocks to the distribution of power, where one of the real-world events that can cause such a shock is intra-elite competition reducing the elites’ ability to coordinate). Similarly, the model allows for only one level of elite, as opposed to the hierarchical ordering of them found in many societies and often considered quite relevant to the development and maintenance of the rule of law to the extent that midlevel elites can facilitate or impede the initiatives of high-level elites.41 Finally, the utility calculations have been constrained in the interest of simplifying the ultimate maximization problem: the elite optimize only over a limited (but well-dispersed) subset of possible bribes, and both mass and elite take account of the magnitude of bribes in calculating the expected behavior of others in a somewhat ad hoc way rather than directly representing the expected utility functions of others. These simplifications should not change the direction or the effect of any of the parameters,42 although they may shift the cut points, for example, at which a given bribe expenditure is large enough to stave off a result, and thus, for example, the point in distributional inequality for given values of the other parameters at which N members of the mass will revolt.

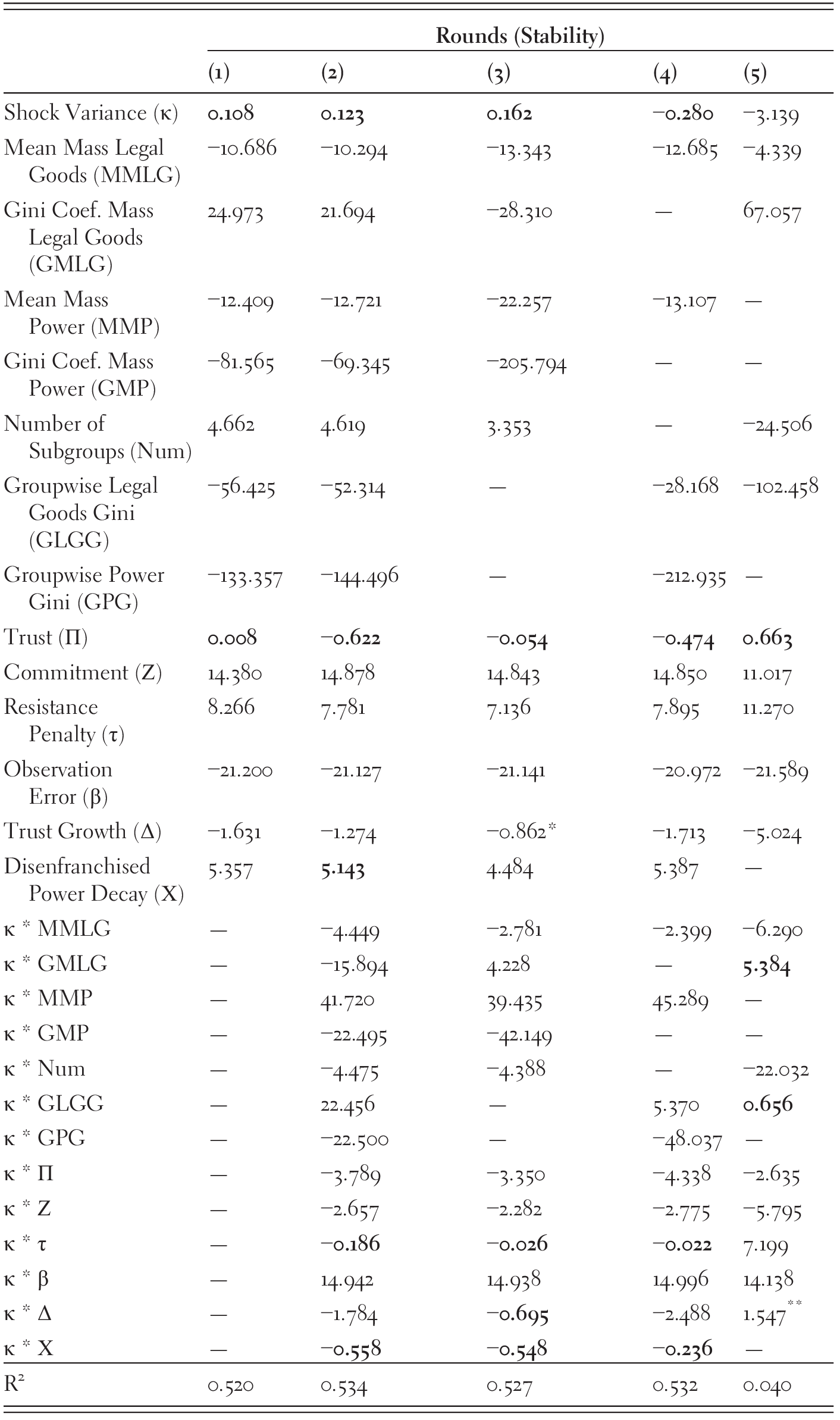

Results of the simulation (run 201,000 times) generally confirm the strategic intuitions laid out earlier, albeit with some reservations and surprises. Table 8.1 represents the coefficients of several slightly different linear regression models, where the dependent variable was the number of rounds – that is, the extent to which initial parameters were stable (88.5 percent of the runs lasted the full 1,000 rounds). Changes between the various models, as can be seen from the table, relate primarily to the inclusion of interaction terms for the shock magnitude parameter κ, the inclusion and removal of terms capturing individual and groupwise inequality in the distribution of goods and power (both of which are derived from the same underlying distribution), and the removal of power parameters. All predictors were centered and scaled for comparability. As almost all predictors are highly significant (the original model output was just filled with triple-star coefficients), for readability I have bolded those that were not significant at a .05 level, and then removed the triple stars from those (majority) that are significant at the .01 level.43 However, it should be noted that the only unambiguously meaningful features of these results are the signs on the coefficients. All else could be artifacts of the specification of the underlying utility functions. (For example, had the coefficients on θ and π been larger, or Π been on a larger scale in the utility functions underlying the simulation, the magnitude of the effect of trust in the results would have been larger.)

Table 8.1 Results of rule of law stability simulation

| Rounds (Stability) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Shock Variance (κ) | 0.108 | 0.123 | 0.162 | −0.280 | −3.139 |

| Mean Mass Legal Goods (MMLG) | −10.686 | −10.294 | −13.343 | −12.685 | −4.339 |

| Gini Coef. Mass Legal Goods (GMLG) | 24.973 | 21.694 | −28.310 | — | 67.057 |

| Mean Mass Power (MMP) | −12.409 | −12.721 | −22.257 | −13.107 | — |

| Gini Coef. Mass Power (GMP) | −81.565 | −69.345 | −205.794 | — | — |

| Number of Subgroups (Num) | 4.662 | 4.619 | 3.353 | — | −24.506 |

| Groupwise Legal Goods Gini (GLGG) | −56.425 | −52.314 | — | −28.168 | −102.458 |

| Groupwise Power Gini (GPG) | −133.357 | −144.496 | — | −212.935 | — |

| Trust (Π) | 0.008 | −0.622 | −0.054 | −0.474 | 0.663 |

| Commitment (Ζ) | 14.380 | 14.878 | 14.843 | 14.850 | 11.017 |

| Resistance Penalty (τ) | 8.266 | 7.781 | 7.136 | 7.895 | 11.270 |

| Observation Error (β) | −21.200 | −21.127 | −21.141 | −20.972 | −21.589 |

| Trust Growth (Δ) | −1.631 | −1.274 | −0.862* | −1.713 | −5.024 |

| Disenfranchised Power Decay (Χ) | 5.357 | 5.143 | 4.484 | 5.387 | — |

| κ * MMLG | — | −4.449 | −2.781 | −2.399 | −6.290 |

| κ * GMLG | — | −15.894 | 4.228 | — | 5.384 |

| κ * MMP | — | 41.720 | 39.435 | 45.289 | — |

| κ * GMP | — | −22.495 | −42.149 | — | — |

| κ * Num | — | −4.475 | −4.388 | — | −22.032 |

| κ * GLGG | — | 22.456 | — | 5.370 | 0.656 |

| κ * GPG | — | −22.500 | — | −48.037 | — |

| κ * Π | — | −3.789 | −3.350 | −4.338 | −2.635 |

| κ * Ζ | — | −2.657 | −2.282 | −2.775 | −5.795 |

| κ * τ | — | −0.186 | −0.026 | −0.022 | 7.199 |

| κ * β | — | 14.942 | 14.938 | 14.996 | 14.138 |

| κ * Δ | — | −1.784 | −0.695 | −2.488 | 1.547** |

| κ * Χ | — | −0.558 | −0.548 | −0.236 | — |

| R2 | 0.520 | 0.534 | 0.527 | 0.532 | 0.040 |

These results indicate that the distributions of power and goods (the latter of which equates to legal rights) dominate the stability results. More unequal power, particularly on the level of groups, most reliably predicts the failure of a simulated legal order, the most obvious reason for this being that such inequality facilitates elite bribery: if one group has much more power than the rest, it may be bribed by elites at lower cost, consistent with the strategic intuitions laid out in this chapter. Likewise, more unequal distribution of goods on the level of groups (although not individuals independent of groups) also strongly predicts the failure of the legal order. Commitment behaves as expected, which again is to be expected if the dynamics of the model are dominated by attempts at bribery of disproportionately powerful groups. Most of the interactions with the shock variance magnitude also behave in predictable ways: as the distribution of power becomes noisier, inequalities in power among mass groups increasingly undermine stability. Several mysteries appear. The ambiguous effect of inequality in goods distributions on an individual level is most plausibly explained as a representation of preference intensity: those who receive more than their fellows have the highest individual commitment, and hence are most likely to resist. However, I cannot fully explain the weak and ambiguous effect of trust. More complex nonlinear analytic strategies might make such anomalies disappear (and would also increase the low overall R2), but only with a severe cost to interpretability; for present purposes the existing analysis is sufficient, and provides moderate support to the overall argument of this chapter.