From the 1960s through the 1980s, Turkish migrants had to contend not only with their growing estrangement from their home country but also with rising racism in Germany. Former guest workers themselves marked the early 1980s as a turning point in their mistreatment in Germany, which represented a stark transition from the “welcome” they recalled having received when they first arrived. “Back then, Turks did not have a bad image,” one former guest worker noted. “To the contrary, every other German said, ‘You were our allies in the First World War.’”Footnote 1 Several other Turkish men, who had been some of the first guest workers to arrive in Duisburg, concurred. The early 1960s “were beautiful and happy times for us all.” “It was an honor,” they recalled, for German firms to employ Turks. But, by 1982, everything had changed. “Now we are like squeezed-out lemons that they want to throw away.”Footnote 2

This interpretation, in some respects, represents a distortion of the past through rose-colored glasses. While the situation had certainly worsened since the 1960s, this interpretation belied the reality that, as this book has shown, Turkish guest workers and their children faced discrimination as soon as they arrived. At the factories and mines where they toiled, they had been crammed into poorly outfitted dormitories, segregated along ethnic lines, and frequently discriminated against by their German coworkers and higher-ups. Amid economic downturns, they had been the first to get fired from their jobs – with managers sometimes, as in the 1973 “wildcat strike” at the Ford factory, justifying their dismissal based on their tardy return from their summer vacations to Turkey. German media outlets had spread sensationalist stories of guest workers’ criminality and sexual abuse, branding Turkish men as hot-headed and impulsive and associating them with their dangerously tempting “Mediterranean,” “Oriental,” and “Asiatic” origins. Internalizing these narratives, German women had often refused – or were afraid – to date Turks. And, all the while, the West German government had been trying to invent strategies for convincing Turks to leave. Many of these experiences of racism remained key features in migrants’ everyday lives over two decades, even as they brought their children and settled into Germany more permanently.

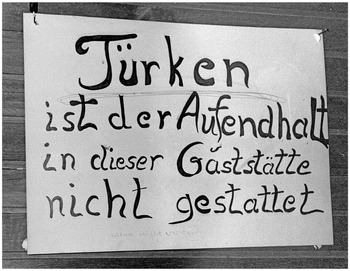

But, as former guest workers rightly observed, the early 1980s were a peculiar beast when it came to racism. A March 1982 poll revealed that 55 percent of Germans believed that guest workers should return to their home country, compared to just 39 percent in 1978.Footnote 3 As the call “Turks out!” (Türken raus!) grew louder, policymakers took harsher action. Whereas they had previously promoted return migration through development aid to Turkey, they increasingly debated whether to unilaterally pass a law that would, in critics’ view, “kick out” the Turks. Importantly, as Maria Alexopoulou has emphasized, West German racism was not only a matter of individual or collective attitudes toward migrants, or of the everyday racism that migrants faced in encounters with Germans, but it was also structural and institutional, pervading all aspects of migrants’ lives (Figure 4.1). It manifested in local, state, and federal legislation, in unequal professional, educational, and housing opportunities, and in migrants’ higher propensity for unemployment and poverty.Footnote 4

Figure 4.1 Emblematic of rising racism, West Germans sometimes banned Turkish clientele from their establishments. This sign in Berlin-Spandau, for example, states: “Turks are not permitted in this restaurant,” 1982.

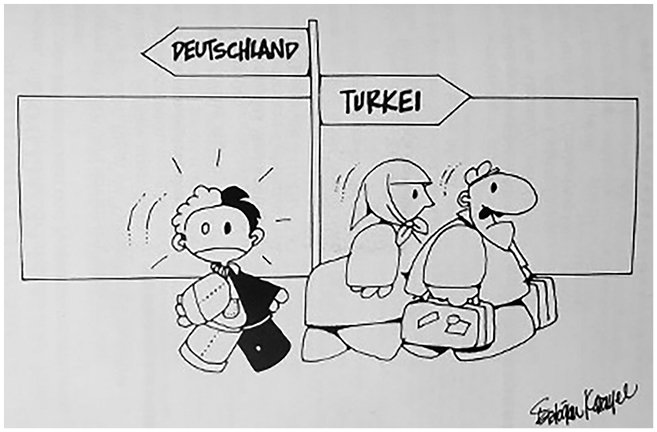

If racism was not a new phenomenon of the 1980s, then neither was the growing emphasis on return migration. The idea of return migration, after all, was embedded in the very logic of the 1961 Turkish-German guest worker program in the ultimately unheeded “rotation principle,” whereby individual guest workers were supposed to return to Turkey after two years and be replaced by new workers. And, of course, discussions of return migration were ubiquitous throughout the 1970s, as the West German government tried – and overwhelmingly failed – to work bilaterally with intransigent Turkish officials on development aid programs in exchange for promoting the workers’ return. But, in the early 1980s, more so than ever before, the dual swords of racism and return migration clashed with and amplified each other with an unparalleled vigor and virulence. The controversial 1983 remigration law, ultimately passed under the conservative government of Helmut Kohl, was, in reality, the culmination of what the social–liberal coalition already wanted.

Given how crucial the 1980s are to this transnational story, the book now turns toward this decade and takes it as a point of focus. Part I, “Separation Anxieties,” told the “Turkish” side of the story: how the migrants became gradually estranged from their home country and perceived as “Germanized” over three decades. Part II, “Kicking out the Turks,” zooms in on just one decade – the 1980s – exposing the nexus between racism and return migration. To set the stage for Part II, the following chapter provides an in-depth exploration of what can be called the “racial reckoning” of the early 1980s, during which West Germans, Turkish migrants, and observers in Turkey all grappled – sometimes self-consciously, sometimes not – with the very nature of racism itself. From editorial boards to parliamentary chambers, from conversations with friends to scathing letters to elected officials, West Germans everywhere engaged with long-suppressed questions that struck at the core of the country’s postwar identity. Had racism disappeared with the Nazis, or did it still exist in West Germany’s prized liberal democratic society? Was racism relegated to neo-Nazis and right-wing extremists, or did it pervade the German population as a whole? Who had a claim to calling someone racist? How could one defend oneself against allegations of racism, and how could Turkish migrants – as the targets of racism – and their home country fight back?

The sheer extent of this racial reckoning in both public and private reveals an important point: even though West Germans overwhelmingly silenced the language of “race” (Rasse) and “racism” (Rassismus) after Hitler, there was in fact an explosion of public discourse about those very words at the very same time that debates about promoting Turks’ return migration surged. This chapter identifies the racial reckoning of the early 1980s as the moment when the linguistic distinction between Rassismus and Ausländerfeindlichkeit crystallized, as Germans heatedly debated whether racism still existed and what they should call it. Ausländerfeindlichkeit ultimately became a more palatable term than Rassismus because it avoided the unsavory connection to Nazi eugenics and biological racism; instead, Ausländerfeindlichkeit connoted discrimination based on socioeconomic problems and “cultural differences” (kulturelle Unterschiede), cast primarily in terms of Turks’ Muslim faith and allegedly “backward” rural origins.Footnote 5 But, as Maria Alexopoulou has rightly argued, Ausländerfeindlichkeit was “just a variation of racism, a phase in which racist thinking won legitimacy again.”Footnote 6 This chapter builds on these interpretations by showing that, despite Germans’ attempts to deny, deflect, and silence their racism, the “older” form of biological racism still reared its ugly head. Not only neo-Nazis but also self-proclaimed “ordinary” Germans condemned Turks as a racial “other” rather than just a cultural enemy who, through their higher birthrates and “race-mixing,” threatened to biologically “exterminate” and commit “genocide” against the German Volk.

The rise in Holocaust memory culture (Erinnerungskultur) in the 1980s is a crucial backdrop for understanding this racial reckoning. Though long suppressed and silenced, West Germans’ efforts to combat the past (Vergangenheitsbewältigung) became a matter of public discussion even more so than amid the “New Left” student protests of the late 1960s.Footnote 7 A crucial spark was the widespread broadcasting of the 1979 American television miniseries Holocaust, which one-third of West Germany’s population – 20 million people – had watched by the following year.Footnote 8 Attention to the crimes of Nazism grew in the mid-1980s amid the “historians’ dispute” (Historikerstreit), which saw leading intellectuals publicly debate the singularity of the Holocaust and the proper role of the memory of the Third Reich in Germany’s present. Simultaneously, the late 1970s and early 1980s witnessed an unprecedented rise in organized neo-Nazism and right-wing extremism, primarily perpetrated by a younger generation of Germans who had not grown up during the Third Reich. The neo-Nazi bombing of Munich’s Oktoberfest in 1980 was the deadliest attack in West German history, stoking fears among policymakers and the public alike that a “Hitler cult” or “Hitler renaissance” was on the rise.Footnote 9

As the memory of the past cast a shadow over the present, antisemitism became intertwined with Islamophobia, and the Nazis’ abuse of Jews became a reference point for West Germans’ abuse of Turks. When viewed from the perspective of both Turkish migrants and their home country, West Germany’s project of commemorating the Holocaust in the 1980s was imperfect, incomplete, and – in many respects – counterproductive to the needs of other minority groups besides Jews.Footnote 10 On the one hand, the rise in Holocaust memory led many Germans to recognize and to warn against the mistreatment of Turks as an unseemly historical continuity – even if they rarely invoked the words Rasse and Rassismus. On the other hand, the emphasis on the singularity of the Holocaust inadvertently made it possible for Germans to sweep the contemporary mistreatment of Turks under the rug. Most egregiously, Holocaust memory provoked a racist backlash among many right-wing Germans, who envisioned the “Turkish problem” as a new sort of “Jewish problem” and whose critique of the growing emphasis on Germans’ collective guilt for the past compounded their denial of Ausländerfeindlichkeit in the present. Holocaust memory, in this sense, was often compatible with racism against Turks.

Focusing only on racist public discourses, however, ignores the very human element of racism – the daily grind of feeling that one does not belong, the constant microaggressions from both strangers and acquaintances, and the fear of physical violence. But despite a tendency to emphasize migrants’ victimhood, neither they nor their home country stayed passive. As historian Manuela Bojadžijev has emphasized, migrants actively resisted racism since the very beginning of the guest worker program: while they rarely rallied explicitly against “racism” throughout the 1960s and 1970s, they organized local protests against a wide range of issues rooted in racism such as exorbitant rent prices, poor living conditions, discrimination in schools, reductions in child allowance payments, and tightened immigration restrictions.Footnote 11 Amid the racial reckoning of the 1980s, Turkish migrants’ rhetoric of resistance evolved even further. They began invoking the language of their oppressor – the hotly debated word Ausländerfeindlichkeit – as a weapon in their anti-racist arsenal. Explicitly casting their discrimination as Ausländerfeindlichkeit allowed them to issue a broader critique that united their multifaceted experiences of structural and everyday racism under a single term that was already prominent in the public sphere. Rising Holocaust memory, too, became a tool for psychologically processing their own mistreatment, helping many – especially children – realize that it was not they, as individuals, who were the problem but rather German society itself.

Criticism of West German racism also resonated transnationally in Turkey – particularly when it came to the drafting of the 1983 remigration law. Paradoxically committed to both preventing return migration and portraying itself as the migrants’ protector, the Turkish government assailed West Germans for violating the migrants’ human rights and trying to kick them out. And in the same breath as they complained about the migrants turning into Almancı, the Turkish media and population regularly compared the treatment of Turks to the Nazis’ persecution of Jews. These accusations were particularly contentious because they emerged immediately after Turkey’s 1980 military coup – the same moment that Western Europeans were assailing Turkey for its own human rights violations. The transnational battle over human rights, democracy, and Holocaust memory not only strained an otherwise friendly century of international relations between the two countries but also revealed hypocrisies, denial, and deflection on both sides.

“I’m Not a Racist, but…”

In 1981, a survey commissioned by the West German Chancellor’s Office revealed a startling conclusion: 13 percent of the German electorate harbored the “potential for right-wing extremist ideology,” 6 percent were “inclined to violence,” and another 37 percent had a “non-extreme authoritarian potential.” An astonishingly large 50 percent veered toward “cultural pessimism,” “anti-pluralism,” and “racism” and felt threatened by “over-foreignization” (Überfremdung). And, perhaps most disturbingly, 18 percent still believed that “Germany had it better under Hitler.”Footnote 12 After an internal leak, the news exploded not only throughout West Germany but also among its crucial Cold War allies, including France, Denmark, Canada, and the United States with headlines like “18 Percent Hail Hitler Era” and “Echo of Germany’s Nazi Past.”Footnote 13 Not surprisingly, many West Germans did not take lightly to being compared to Hitler. Writing to the Chancellor’s Office, one man dismissed the results as “incomprehensible” and insisted that out of all his acquaintances – some 300–400 people – “I do not know a single one with that worldview!”Footnote 14 And Uwe Barschel, the Schleswig-Holstein Interior Minister, lambasted the survey as an “insult to the German Volk.”Footnote 15

The next year, the notorious Heidelberg Manifesto sprung to the forefront of public discourse. First published in the right-wing Deutsche Wochenzeitung, the manifesto cloaked racism in the guise of academic legitimacy, as it was signed by fifteen professors at major universities.Footnote 16 “With great concern,” the professors wrote, “we observe the infiltration of the German Volk through an influx of millions of foreigners and their families, the infiltration of our language, our culture, and our traditions by foreign influences.” Describing the “spiritual identity” of the German Volk as based on an “occidental Christian heritage” and “common history,” they cast Turks, Muslims, and other “non-German foreigners” as fundamentally incompatible. Alongside this culturally based argument, however, was blatant biological racism reminiscent of eugenics and Hitler’s Mein Kampf. “In biological and cybernetic terms,” they continued, “peoples are living systems of a higher order with distinct system qualities that are passed on genetically and through tradition. The integration of large masses of non-German foreigners is therefore not possible without threatening the preservation of our people, and it will lead to the well-known ethnic catastrophes of multicultural societies.” Preempting criticism, they claimed to “oppose ideological nationalism, racism, and every form of right- and left-wing extremism” and asserted that their desire to “preserve the German Volk” was firmly rooted in the Basic Law. Despite this denial of racism, mainstream media condemned the manifesto for being full of “prejudices, banalities, barroom wisdom, and bombastic definitions” and stoking the fires of “nationalism” and “racism.”Footnote 17

Also widely circulating at the time was a thirty-page pseudoscientific rant titled Ausländer-Integration ist Völkermord (Integrating Foreigners is Genocide), written by retired police chief Wolfgang Seeger in 1980. Eschewing the mainstream parties’ general definition of “integration” as a reciprocal process in which cultures could be preserved, Seeger criticized the term as a proxy for “assimilation” or “Germanization”: a “merging, melting, and mixing” of foreigners into the “body of the German Volk” that “contradicts the laws of nature.” Arguing that culture was determined by both “race” and “genetics,” he warned that Germany would devolve first into “racial conflict” and eventually, through sex and intermarriage, into a “Eurasian-Negroid future race.” All future offspring would be “half-bloods” (Mischlinge), he insisted, invoking the Nazi category codified in the 1935 Nuremberg Laws to denote certain Jews, Roma, and Black Germans whom the Nazis deemed genetically part-“Aryan.” The overall consequences would be a dual “genocide” (Völkermord) – not only of the German Volk but also of the foreigners. The only way to prevent this genocide was for the “simple man” and the “simple woman of our Volk” to protest through democratic means and write their representatives demanding that they send foreigners home.Footnote 18

As the call “Turks out!” echoed throughout the country, policymakers began hardening their stance on how to solve the “Turkish problem.” In December 1981, Chancellor Helmut Schmidt’s SPD-FDP government proposed an “immigration ban” (Zuzugssperre) that would lower the upper age limit for foreign children whose parents resided in Germany from eighteen to sixteen.Footnote 19 Two months later, return migration became the focus of a heated federal parliamentary debate, which transformed into a microcosm of the broader public reckoning with the existence, nature, and language of racism. The CDU/CSU opposition leader, Alfred Dregger, denied the feasibility of integrating Turks and expressed his party’s staunch commitment to promoting return migration. Despite the secularization of Turkish society, Turks’ “Muslim culture” and “distinct national pride” allegedly prevented them from being culturally “assimilated” or “Germanized,” and even socially “integrating” them into schools and jobs would be “difficult.” Promoting return migration validated the “natural and justified sentiment of our fellow citizens,” Dregger noted, and was “in no way immoral.” CDU/CSU representatives also proved eager to deny and deflect their racism altogether. “We have no reason to be accused of Ausländerfeindlichkeit by domestic or foreign critics when we insist that the Federal Republic should not become a country of immigration,” Dregger explained. The current popular outcry, added CSU representative Carl-Dieter Spranger, was not an expression of “nationalistic arrogance,” “racist incorrigibility,” or an “ausländerfeindlich attitude,” but rather a reaction to the failed policies of the SPD-FDP.

On the other hand, the SPD and FDP both tied the issue of return migration fundamentally to Ausländerfeindlichkeit, the legacy of the Third Reich, and the language of human rights and morality. SPD representative Hans-Eberhard Urbaniak opened the debate by asserting firmly: “We clearly and unambiguously reject any policy of ‘Foreigners out,’” and “We must all emphatically fight against Ausländerfeindlichkeit.” Although the SPD’s coalition partner did not necessarily reject the promotion of return migration in theory, FDP representative Friedrich Hölstein cautioned that convincing Turks to “voluntarily return” might result in a policy of “forced deportation.” Morally, such a policy would contradict West Germans’ “responsibility” to atone for their “national history” of Nazism and to uphold their Cold War commitment to “human rights and human dignity.” The optics alone would be detrimental, Hölstein asserted: “Do we really want to be internationally charged for violations of human rights? We, of all people, who continue to rightly point out human rights violations in the other part of Germany and throughout the world?”

Invigorated by the debate, the SPD-FDP government began developing a state-driven “campaign against Ausländerfeindlichkeit.”Footnote 20 Strikingly, the Federal Press Office’s proposed messaging strategy made no mention of migrants, let alone of the need to express sympathy toward them. Instead, it portrayed Ausländerfeindlichkeit as a threat to Germans: “Ausländerfeindlichkeit is immoral; we cannot afford to fall back into nationalistic thinking. Ausländerfeindlichkeit endangers inner peace and accordingly the democratic state. It damages our reputation and all of us.” As one staffer wrote, if the “caricature of the ‘beastly German’” resurfaced on the world stage, it would destroy the “hard-earned sympathy” that Germans had rebuilt over the past four decades.Footnote 21 Although this coordinated public relations campaign never materialized, it demonstrates that West German policymakers envisioned the task of combatting Ausländerfeindlichkeit not only as self-serving but also as fundamentally connected to the memory – or forgetting – of the Nazi past.

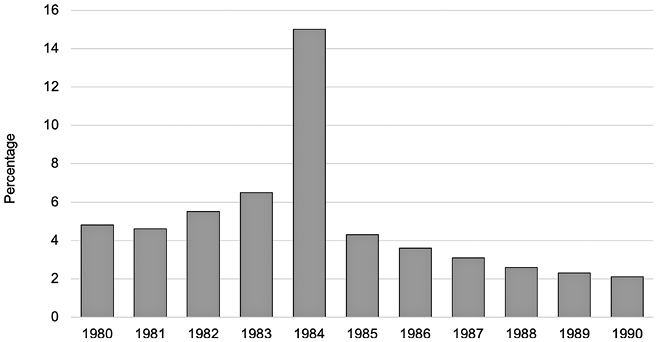

Beyond surveys, media coverage, and parliamentary debates, however, understanding how ordinary Germans justified and expressed their own racism was – and is – no easy feat: they often criticized Turks privately, in passing, and in conversations with friends and family. But the West German government did have other sources they could examine, ones that testified more to everyday attitudes: letters they received from citizens. In fact, between 1980 and 1984, President Karl Carstens received no fewer than 202 letters from individual Germans complaining about foreigners and demanding – in one way or another – “Turks out!” Whether three-sentence postcards or ten-page rants, whether scribbled in illegible handwriting or meticulously typed, 50 percent of the writers complained about Turks explicitly, whereas other migrant groups – from Yugoslav guest workers to Vietnamese asylum seekers – were mentioned in fewer than five letters each. Although the letters ranged in tone from civil and matter-of-fact to irreverent and vulgar, the president’s aide tasked with reading them cataloged them under the all-encompassing label “Ausländerfeindlichkeit.” The lumping together of these diverse letters reveals that, for the aide, any criticism of Turks, no matter how mild, was indicative of Ausländerfeindlichkeit.

Analyzed together as a dataset, these letters are a crucial source for uncovering the bottom-up history of German racism in the early 1980s because, unlike surveys, they capture the specific patterns, nuances, and raw visceral emotion with which Germans expressed and attempted to justify their concerns about Turks.Footnote 22 In fact, Christopher Molnar has examined another set of letters written to the subsequent president, Richard von Weizsäcker, in the early 1990s, coming to a similar conclusion about the persistence of biological racism and “apocalyptical fear.”Footnote 23 The letter writers’ names and addresses indicate that they were relatively evenly split by gender and lived all throughout the country, from cities to smaller towns. They were not politicians, journalists, intellectuals, or other elite shapers of public opinion. Nor do most of them come across as hardcore neo-Nazis hellbent on mass murdering foreigners and bringing about the restoration of the Third Reich, or even as voters of the right-wing National Democratic Party (NPD). Instead, to distance themselves from radical right-wing extremists, many identified themselves mundanely: a “concerned citizen,” “normal German,” “retired man,” “average woman,” “housewife,” or “elementary school student,” who believed in airing their grievances through formal democratic channels. Still, their alleged “ordinariness” demands scrutiny. On the one hand, the claim of being an “ordinary citizen” was a form of self-styling that helped these letter writers rhetorically distance their beliefs from those of right-wing extremists. On the other hand, many of them were likely the so-called Wutbürger, or angry citizens who regularly sent politicians scathing letters about various issues or public statements. In fact, many of these writers explicitly referenced a June 10, 1982, interview with Carstens, in which he stated that foreigners are our “fellow citizens” (Mitbürger) and called upon Germans to “thank foreigners for contributing to the welfare of our country,” to “help foreigners feel at home here,” and to “oppose all forms of Ausländerfeindlichkeit.”Footnote 24 Carstens’s statement had incensed them.

Collectively, the hundreds of letters to Carstens speak strongly to the silences, denial, and deflection surrounding not only the word Rassismus but also the allegedly more palatable word Ausländerfeindlichkeit. Strikingly, one-fourth of the writers – some fifty people – explicitly denied that they harbored racist or ausländerfeindlich views. A common strategy was to preface a long letter ranting about Turks and other migrants with variations on a simple phrase: “I’m not a racist, but…,” “I’m not an Ausländerfeind, but…,” “I’m not a right-winger, but…,” “I’m not an extremist, but….,” “I’m not a neo-Nazi, but…”Footnote 25 Many objected to the term Ausländerfeindlichkeit itself. Claiming that Ausländerfeindlichkeit was “overhyped” and little more than a “stupid buzzword,” several insisted that their concerns were a “reasonable critique of particular problematic developments” and a “justified rage.”Footnote 26 “Whenever someone stands up and expresses his concern about foreigner policy,” decried Jürgen Feucht, he is “immediately vilified as a ‘fascist’ or ‘neo-Nazi.’”Footnote 27 This “tactless” association, claimed Kurt Nagel, denigrated them into “unteachable, irredeemable, conservative reactionary people with narrow-minded prejudices or people who support political demagoguery.”Footnote 28 By differentiating themselves from neo-Nazis and right-wing extremists, these “ordinary” Germans deflected their guilt: they contended that their concerns, articulated through words rather than violence, were rational and justified.

Far more vividly than surveys alone, the letters to Carstens also reveal the multifaceted reasons why Germans opposed foreigners. By far the most important was the perception of foreigners’ culpability for Germany’s socioeconomic woes: half of the letters mentioned unemployment, while one-third mentioned guest workers’ perceived abuse of the social welfare system. Fred Reymund called all foreigners a “lazy Volk” and complained that West Germans “have to support the Third World.”Footnote 29 Irmtraud Wagner, a 61-year-old woman, asserted that Turks’ exploitation of the social welfare system made them wealthier than many German retirees, whose meager pensions left them “degraded into beggars.”Footnote 30 Two particularly inflammatory issues were family reunification and the child allowance benefit (Kindergeld), both of which had been consistent points of contention for the past decade.Footnote 31 Alongside the image of the exploitative “welfare migrant,” nearly 20 percent of the letters referenced the changing neighborhoods and establishment of ethnically homogenous “Turkish ghettoes,” such as Berlin’s heavily Turkish neighborhood of Kreuzberg, and the challenges posed to the education system by the high percentages of migrant children.

Along with unemployment and alleged abuses of the social welfare system, perceived threats to public safety were another leading concern of letter writers. One-third referenced the migrants’ criminality, lamenting that West Germany had become a “paradise for criminals” and that the jails were filled with “criminal foreigners.”Footnote 32 While these complaints focused primarily on drug trafficking, 10 percent centered on sexual violence – a crime that, due to longstanding Orientalist tropes, was particularly associated with Turkish and Middle Eastern men. Two elderly women, Ingeborg Hoffmann and Helma Zinkel, each noted that German women and girls could not walk down the street even in broad daylight because Turkish men viewed them as “prey.”Footnote 33 In the most troubling letter, a thirteen-year-old girl relayed her traumatic experience of being sexually assaulted by a group of Turkish teenagers who – “like they always do” – were loitering at a park after dark. Although she and her friend attempted to avoid “the group of foreigners,” they “came up to us and grabbed me, in order to flagrantly touch me.” The incident, the girl suggested, was not isolated, but rather characteristic of foreign men as a whole: “Have we reached the point in Germany that we, at thirteen years old, can no longer be outside at 7 o’clock at night without being molested by foreigners? … Pity, poor Germany!”Footnote 34 Given that no other children sent letters, it is possible that this letter was written by adults posing as a thirteen-year-old girl to draw the president’s attention to a particularly egregious case of sexual violation.

Twenty percent of the writers expressed cultural racism through condemning Turks’ Muslim faith. Far more harshly than simply pointing out that the two cultures were “different,” most of these writers took a particularly essentialist and racialized view of Islam, with Ingrid Eschkötter denigrating Turks as a “disgusting Mohammedan Volk” and another writer demanding that the government “Kick out the Turks, this Muslim scum!”Footnote 35 Only four of the writers mentioned headscarves – a reflection that the letters were written primarily by political centrists and conservatives rather than the leftist feminists who since the late 1970s had begun to condemn Muslim migrants’ perceived patriarchal treatment of women.Footnote 36 Instead, they portended a “fearsome” future of Germany’s “Islamicization by infinitely primitive Turks,” in which Germans would “burn the Bible and switch it out for the Koran!” and the Muslim call to prayer would “drown out the church bells.”Footnote 37 Muslims’ Halal dietary restrictions, they further contended, not only made them unwilling to eat Germany’s pork-based national cuisine but also posed a physical threat. As Georg Walter wrote, Turks “consider us Germans to be pork eaters, whom they can cheat, steal from, and even murder.” Recycling longstanding antisemitic tropes regarding the Jewish law of Kashrut, they insisted that the process of preparing Halal meat – ritually and humanely slaughtering the animal by cutting its throat and letting it bleed out – was a violent attack on innocent life that could lead to future violence. “They slaughter humans like they do sheep,” declared Ellie Schützeberg, a housewife and grandmother married to a retired police officer.Footnote 38

In associating Islam with primitivity and violence, several writers reiterated Orientalist tropes rooted in the centuries-old Ottoman-Habsburg conflicts. They warned that Germans would soon suffer the “downfall of the Occident,” succumb to the rule of “Christian slaughterers” and the “plundering Volk from the empire of Allah,” and be inundated by “Mustafas, Mohameds, and Ali Babas” walking around in “Oriental robes.”Footnote 39 The fear of the Turks exists “everywhere where Turks show up in large masses,” one man stated matter-of-factly, imploring Carstens to “think of the Mohács, the entire Balkans, and Vienna.”Footnote 40 The 1683 Battle of Vienna, when the Ottoman army stormed the gates of the Habsburg capital, proved a particularly powerful reference point. “Did the friendship with the Turks begin 300 years ago at the gates of Vienna?” Heinz Schambach quipped, while Berta Maier suggested that Süleyman II, the Ottoman emperor during the 1683 battle, would be “rolling in his grave because he hadn’t come up with the idea of guest workers.”Footnote 41 Georg Kretschmer emphasized Ottoman violence in the modern era, recalling the 1915–1916 Armenian Genocide in which “the Turks tried to exterminate the Armenians with the most brutal of methods.”Footnote 42 The irony that the legal definition of genocide would not have existed without Germans’ having perpetrated the Holocaust was lost on them.

These socioeconomic concerns and cultural racism were compounded by the increase in asylum seekers migrating to West Germany in the early 1980s.Footnote 43 Lambasting asylum seekers as criminals, many of the writers argued that they were “fake asylum seekers” (Scheinasylanten) or “economic refugees” (Wirtschaftsflüchtlinge) who lied about their political persecution in order to seek jobs in West Germany and exploit the country’s welfare system. Criticism of asylum seekers applied most harshly to the thousands of Turkish citizens, predominantly Kurds, who applied for asylum following Turkey’s September 1980 military coup. Most of the writers conflated asylum seekers and guest workers from Turkey into one homogenous category of migrants who, as one writer pointed out, wanted to turn West Germany into a “hotbed for the expansion of Greater Turkey.”Footnote 44

For 10 percent of the writers, the “Turkish problem” was inextricable from the Cold War context. Several facetiously asserted that even East German dictatorship and poverty was preferable to the large proportion of foreigners in West Germany, although such statements erased the thousands of contract workers and asylum seekers living in East Germany. “It’s probably nicer to live in the GDR than in our own country among Asians and Africans,” scribbled Ernst Bender on a three-sentence postcard, while Ellie Schützeberg concurred: “I’d prefer to go back to the GDR, which I left 39 years ago and where I would be protected and safe from this Türkenvolk.”Footnote 45 Volker Arendt from Iserslohn contended that reunification could only be achieved if Germans on both sides of the Berlin Wall embraced “the feeling that we are a nation with a collective past, culture, and language,” noting that a high proportion of foreigners “without any connection” to the other part of Germany would impede this process.Footnote 46 Ottilie Vogel, an elderly woman, put it even more blatantly: “GDR citizens do not want reunification with an Orientalized FRG.”Footnote 47

The letters also reflect Germans’ efforts to distance themselves from the Nazi past. A remarkable 20 percent of the letters referenced Hitler, Nazism, and World War II. To support their claim that they were not right-wing extremists or neo-Nazis, several of the elderly writers emphasized that they had resisted the Third Reich. Peter Bursch claimed that he had been “thrown out” of the Hitler Youth and had only fought in World War II because he was a “good soldier” and the war “was about Germany, not about Hitler.”Footnote 48 Another denied that he was a “right-wing pig” by claiming that he had been an “iron antifascist,” that his two best friends were Jews, and that his own great-grandfather had been Jewish. In another selective interpretation of the past, some writers criticized Turks in relation to postwar narratives of German victimhood. Twenty percent rejected the argument that Germans should thank guest workers for helping rebuild the country after World War II. Alfred Gonska from Essen, who boasted that he had participated in “clearing the rubble” of cities that had been bombed into “debris and ashes,” insisted that the task of Germany’s rebuilding was undertaken by “all Germans, and only Germans, under unspeakably immense sacrifices and difficulties and with great idealism.”Footnote 49 Several writers also compared guest workers and asylum seekers to the twelve million ethnic German expellees (Heimatvertriebene) who fled Eastern Europe for Germany in 1945.Footnote 50 Identifying herself as an expellee, Elisabeth Stellma complained that today’s migrants were receiving too generous treatment even though they were not ethnically Germany: “Back then, no one cared if we had nothing to eat.”Footnote 51

On the other hand, the letters also demonstrated continuities of Nazi ideology and terminology. Georg Kretschmer criticized migrants for West Germany’s perceived overpopulation by invoking the Nazi phrase “Volk without space” (Volk ohne Raum), while three other writers used the highly taboo term “living space” (Lebensraum), the Nazi ideology that justified expansion, war, and genocide in terms of an existential need to secure land, food, and natural resources for “Aryan” Germans.Footnote 52 Several others, including 70-year-old Irmgard Recke, mentioned “Rump Germany” (Restdeutschland) – a rhyming play on the German word for West Germany (Westdeutschland) – which, in the early Cold War decades, opponents of Germany’s division had used to criticize West Germany as the meager leftover half of Germany following the break-off of the GDR.Footnote 53 But the term “Rump Germany” had a deeper history. After World War I, “Rump Germany” became a rallying cry against the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, which stripped the former German Empire of 13 percent of its European territories and all its overseas colonies. As the desire to restore “Rump Germany” to “Greater Germany” became central to the Nazi expansionism, invoking the term during the Cold War reflected nostalgia for the Third Reich.Footnote 54

A striking continuity to eugenics was the persistence of biological racism, dehumanizing language, judgments based on skin color, and the term “race” (Rasse) itself. Overwhelmingly, the writers who invoked the language of “race” tended to be elderly retirees, who had lived through the Third Reich and had been indoctrinated into Nazi ideology. Germany did not just have a “foreigner problem,” explained Dieter Baumann from Würzheim, but rather a “racial problem” (Rassenproblem) caused by “colored” (farbige) migrants.Footnote 55 Wilhelmine Richtscheid, a retired woman from Münster, cast Turkish nationality as a skin color and railed against “yellow, brown, black, and Turkish” asylum seekers.Footnote 56 A former World War II soldier, Werner Weber, complained that Turks were a “hard to discipline race” and warned against the “yellow danger” (gelbe Gefahr) of Vietnamese asylum seekers.Footnote 57 After fleeing East Germany’s socialist dictatorship in 1949, Hedwig Kubatta bemoaned that she was now forced to live together with “Negroes, Turks, and other half-apes.”Footnote 58

The letters also included defamatory tropes surrounding “race-mixing” (Rassenmischung), a eugenic concept that the Nazis had taken to the extreme in the 1935 Nuremberg Laws that banned sexual relations between Jews and “Aryans” and categorized part-“Aryans” as “half-bloods” (Mischlinge). Although only one of the writers explicitly mentioned the Nuremberg Laws’ criminal category of “racial defilement” (Rassenschande), several cautioned against the perils of sexual reproduction between individuals of “different Völker and Rassen,” which posed the “danger that individual races would be destroyed.”Footnote 59 Two of the writers who invoked the most blatant Nazi terminologies, Hedwig Kubatta and Georg Kretschmer, contended that Germany had already become a “dirty Mischvolk” and asserted that integrating foreigners was “unnatural” because “God did not put any Mischvölker on this earth.”Footnote 60 In particularly eugenic and dehumanizing language, 80-year-old Hugo Gebhard warned that if “various skin colors and face shapes” came to West Germany, the country would devolve into a “zoological garden” that, just like the “mixed society” (Mischgesellschaft) of the United States, would be plagued by “race riots” (Rassenunruhen).Footnote 61 Jürgen Feucht and Heinz Schambach both invoked the term “Eurasian-Negroid future race” (eurasisch-negroiden Zukunftsrasse), directly citing Seeger’s pamphlet “Integrating Foreigners is Genocide.”Footnote 62 In this sense, several insisted that their opposition to Turks was not a matter of racism or Ausländerfeindlichkeit but rather a “natural” and “very healthy” “self-preservation instinct.”Footnote 63

Further mobilizing Seeger’s inflammatory rhetoric of “genocide,” many writers argued that “race-mixing” threatened the “biological downfall of one’s own Volk.”Footnote 64 These fears were particularly common among the 25 percent of writers who criticized migrants’ high birthrates. Berta Maier, one of the most vociferous critics, complained that Turkish women – with their “wombs always full” and their children “multiplying like mushrooms” – were committing an “embryo mass murder” or a “new style of genocide” against Germans.Footnote 65 Turning the blame on West Germans themselves, Bernhard Machemer from Osthofen said that West Germans were committing a “Volk suicide” (Volkssuizid) by allowing themselves to become the “modern slaves of the foreigners.”Footnote 66 Seven letters invoked the parallel term “extermination” (Ausrottung), with two directly referencing the genocide of Native Americans perpetrated by Europeans conquering the Americas. Only one letter, from Alfred Kolbe of Nuremberg, alluded to Germans’ “genocide” or “extermination” of Jews, but it did so in a way that absolved Germans of guilt: “This is the fate of the German Volk, just as what happened to the Jewish Volk.”Footnote 67

Showing no remorse for the victims, 5 percent of the writers blamed the “Turkish problem” on Jews and Roma, the latter of whom they continued to stigmatize as “Gypsies” (Zigeuener). Sigismund Stucke, who expressed his strong commitment to protecting the “still existing German Reich,” demanded that the government hold a popular referendum on a simple yes-or-no question: whether “Jews and other foreigners” should be allowed to stay in West Germany.Footnote 68 Rudolf Okun from Hunfeld argued that mass migration was a conspiracy concocted by an amorphous “world Jewry” (Weltjüdentum) that, invoking the derogatory Yiddish term for non-Jews, sought to “destroy all goyim.”Footnote 69 Reflecting the connection between Islamophobia and anti-Zionism, one writer argued that “the current anti-Turkish Ausländerfeindlichkeit is actually an act of revenge by the state of Israel” and by the entire “Jewish race.” Several, moreover, demanded that Germany “kick out the Gypsy gangs,” who were “murderers,” “gang robbers,” and “parasites.”Footnote 70 Turkish children, ranted Ilse Vogel, were so unkempt that they “look like Gypsy children,” while Georg Walter warned that “Germany is on its way to becoming a motley international Gypsy Volk.”Footnote 71

Expressing varying degrees of Holocaust denial and revisionism, Heinz Schambach and several other writers condemned the “guilt complex” (Schuldkomplex) or “collective guilt thesis” (Kollektivschuldthese), which portrayed all Germans as culpable for Nazism. Jürgen Feucht railed against the media’s “endlessly prostituted” rhetoric of “previously-we-murdered-six-million-Jews-and-now-the-foreigners-are-next,” while Robert Streit complained that the current media was “worse than under [Joseph] Goebbels,” the Nazi propaganda minister.Footnote 72 Calling the widely broadcasted 1979 miniseries Holocaust a “fictional, lying hate film” (Hetzfilm), Margarete Völkl complained that the fixation on the “so-called ‘German past’” was denigrating Germans as “immoral, criminal, horrible, and ausländerfeindlich.” She further espoused a frequent neo-Nazi rallying cry: demanding the release of Nazi Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess, now eighty-eight years old, who had been serving life in prison since 1945. Hess, Völkl cried, was “innocent,” his family was “suffering greatly,” and his imprisonment was “inhumane!”Footnote 73 Yet, in one of the most unconvincing denials of racism, she questioned: “Why do they have to call us Nazis?”

From complaints about unemployment, to racialized and Orientalist criticism of Islam, to blatant Holocaust denial, the wide range of opinions in these letters reveals the nuances and patterns of West German racism in the early 1980s. Despite attempting to justify their criticism as “rational” and “legitimate,” these self-proclaimed “ordinary Germans” inadvertently exposed themselves as harboring the same racial prejudices that they tried to suppress. Emphasizing cultural racism alone belies that 10 percent of them displayed biological racism: they invoked Nazi terminology, ranted about inferior “races,” decried “race-mixing,” and bemoaned the “biological downfall,” “genocide,” or “extermination” of the German Volk. They denied or downplayed the Holocaust and denigrated Jews and Roma as connected to – and even responsible for – the “Turkish problem.” While not a single writer praised Hitler, drew a swastika, or tied themselves directly to organized neo-Nazism, they had clearly absorbed the messages of sensationalist mainstream media and right-wing extremist tracts. And the knowledge that policymakers were drafting a law to promote guest workers’ return migration normalized their racism as politically legitimate.

Everyday Racism and Anti-Racist Activism

Racism, however, was also an everyday phenomenon and a collective experience, with real material and physical consequences for Turkish migrants. But crucially, the migrants fought back. If the early 1980s saw a rise in racism, then they also witnessed an attendant rise in anti-racist activism. Although Turks’ anti-racist activism has generally been underacknowledged in the memory of the guest worker program, it is important to emphasize that Turkish migrants played an active role in the racial reckoning of the 1980s, challenging West German society to confront uncomfortable and silenced truths. Both individually and collectively, they worked to defend themselves against both structural and everyday racism. Forms of racism ranged from anti-Turkish jokes and slurs to discriminatory treatment in workplaces, schools, and neighborhoods and – importantly for this book – the drafting of the 1983 remigration law. Anti-racism, like racism itself, took many shapes.Footnote 74 It was usually peaceful but sometimes violent. It was public and private, loud and quiet, political and personal. It was a matter of looking outward and searching inward. Ultimately, everyone had their own relationship to anti-racist activism, guided by common but sometimes unspoken goals: improving their status, securing better treatment in their everyday lives, and staking a claim to membership in West German society while still maintaining ties to home.

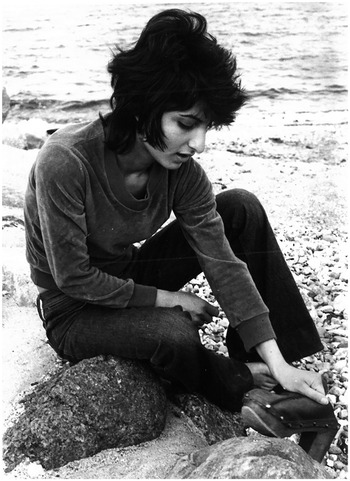

In the overall memory of the racial reckoning of the early 1980s, one of the most striking and powerful anti-racist protests is the case of the young Turkish-German poet Semra Ertan (Figure 4.2). Born and raised in the port city of Mersin on Turkey’s Mediterranean coast, Ertan had migrated to Kiel in 1971 at the age of fifteen to reunite with her parents, both of whom were guest workers of Alevi background. As she entered adulthood, leveraging her language skills to write poetry and work as a German-Turkish interpreter, she felt growing estrangement from both countries. While poetry provided a creative outlet to privately express her concerns, she turned to public anti-racist activism. Her many hunger strikes, however, had gone unnoticed. In a final attempt to bring attention to racism, she resorted to committing suicide publicly. On May 24, 1982, just one week before her twenty-sixth birthday, she doused herself with five liters of gasoline and set herself on fire in the middle of a busy street corner in Hamburg. Although a police officer rushed to smother the flames with blanket, she died in the hospital two days later.

Figure 4.2 Semra Ertan, Turkish-German poet and anti-racism activist, ca. 1980. Ertan brought transnational attention to West Germans’ mistreatment of Turks when she committed suicide publicly in protest in Hamburg.

The suicide of Semra Ertan is a powerful reminder that Turkish migrants’ experiences of racism were – all at once – personal, public, and politicized, with effects that crossed national borders. Calculated and deliberate, Ertan intended for both Germans and Turks to understand her suicide as an act of anti-racism. To ensure that her message spread, she had notified two of West Germany’s largest news outlets ahead of time. One reporter rushed to speak with her. In their interview, later printed verbatim in newspapers in both West Germany and Turkey, she made her protest clear. “The Germans should be ashamed of themselves,” she insisted. “In 1961, they said, ‘Welcome, guest workers.’ If we all went back, who would do the dirty work? … And even if they did, who would work for such a low wage? They would certainly say: No, I would not work for such a low wage.” She concluded powerfully: “I want foreigners not only to have the right to live like human beings, but rather to also have the right to be treated like human beings. That is all. I want people to love and accept themselves. And I want them to think about my death.”Footnote 75

Ertan’s call to action, however, was hotly contested both within and across borders. Reflecting the broader debates over racism, Ertan’s suicide elicited mixed responses from West German politicians. While local SPD and Green Party representatives admitted that Turks were facing a “concrete threat” that could “move in the direction of pogroms,” a CDU representative cautioned against “generalizing” Ertan’s case, since the “overwhelming majority of Germans do not hate foreigners.”Footnote 76 Ignoring her anti-racist motivation entirely, Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher dismissed her suicide as “an act of desperation,” while the State Interior Minister of Schleswig-Holstein called her a “victim of her own problems.”Footnote 77 To be sure, Ertan had struggled greatly with her mental health, and she had previously attempted suicide. For politicians, however, emphasizing her mental health problems served the political purpose of deflecting attention away from racism. Such victim-blaming not only repeated gendered tropes of female psychiatric problems, but also reflected a pervasive tendency to attribute the “Turkish problem” to Turks’ alleged unwillingness to integrate rather than to West Germany’s lack of any comprehensive policy to integrate them.

In Turkey, observers were far more eager to emphasize Ertan’s suicide as an anti-racism protest. Whereas West German reports of the suicide faded after several days, Turkish newspaper coverage persisted for weeks on end, condemning West German politicians’ dismissive responses. In a Milliyet interview, her father attributed her suicide to West German policy, rightly pointing out that just two weeks before her suicide, Chancellor Helmut Schmidt had announced that foreigners should either integrate into Germany or go home.Footnote 78 Hürriyet published a multi-page feature on how her suicide had affected her friends, neighbors, and family in her Turkish home city of Mersin, juxtaposing photographs of her repatriated casket with those of her happy childhood before she followed her parents to Germany, where “the true tragedy began.”Footnote 79

The week after her suicide, Hürriyet published a short blurb urging Turks in Germany to write directly to the West German president. Hürriyet’s sample letter, printed in both languages, read: “We as members of the Turkish minority who have been working in Germany for many years deplore the recent events. We are suffering the most under unemployment, and Ausländerfeindlichkeit threatens our very existence. The aggressors are known, but no action is taken against them. On the other hand, we also pay taxes and contribute to Germany’s welfare. Is ‘peace’ not our right? Our request to you is to urgently pass a law against Ausländerfeindlichkeit.”Footnote 80 The call resonated broadly. The president’s office received fifty-six letters with the verbatim text, one of which had twenty-six signatories, while a dozen others wrote their own messages. Reflecting the importance of Ertan’s suicide, one attached the Hürriyet newspaper article about the funeral in Mersin, while others noted that “a woman in Hamburg set herself on fire” and that “there are others like Semra.”Footnote 81 Most extremely, one woman threatened: “If this situation does not change immediately, then I too will set myself on fire in the middle of the street like Semra Ertan, because we are sick and tired of this horrible treatment and we want to be free of it.”Footnote 82

As these letters reflect, Ertan’s suicide resonated so deeply and personally not only because of sympathy toward her as a young woman, but also because her protest spoke to a collective everyday experience of anti-Turkish racism. Even when simply walking down the streets, the migrants had metaphorical targets on their backs. Speaking Turkish, or speaking German with a Turkish accent, was an audible marker of difference. And West Germans’ racialization of Turks as predominantly dark-skinned with so-called “Mediterranean,” “Oriental,” or “Asiatic” features made many migrants – especially women and girls who wore headscarves – visually identifiable even before they spoke. Some migrants, however, recalled that they experienced less overt discrimination because they were able to racially “pass” as German due to their blonde hair and blue eyes.Footnote 83 One girl also explained that because her parents came from Istanbul, were educated, and were “western-minded,” she was better able to fit in socially and culturally with Germans.Footnote 84 Nevertheless, because Germans tended to homogenize Turks as coming from predominantly rural areas, Turks’ ability “pass” on the basis of urban origins was limited.

Germans verbally assaulted them with racist slurs, whether screaming at them across the street or mumbling quietly on streetcars. Besides more generic hateful names like “shit Turks” (Scheiß-Türken) and “Turkish pigs” (Türken-Schweine), these slurs also reflected age-old Orientalist stereotypes. Especially common were insults like “camel driver” (Kameltreiber), “garlic eaters” (Knoblauchfresser), and “cumin Turk” (Kümmeltürken), which associated Turks not only with the seemingly “exotic” foods that they brought to West Germany’s otherwise bland culinary scene, but also with backwardness and underdevelopment. Increasingly throughout the 1980s, the racial slur Kanaken – which Germans had applied since the early twentieth century to an evolving variety of primarily working-class migrant populations from Southern and Eastern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East – became nearly exclusively associated with Turks.Footnote 85

Alongside foreboding signs banning them from entering German businesses, migrants also confronted racist graffiti spray-painted by organized neo-Nazis or just rowdy teenagers looking for a laugh. In one iconic photograph taken in Berlin-Kreuzberg, a Turkish man named Ali Topaloğlu and his two young nieces walk somberly past graffiti that states “Turks out!” (Türken raus!).Footnote 86 Given the strong emotions that this image evoked, it was reprinted in media outlets throughout West Germany, including on the front page of Metall, the publication of the metalworkers’ trade union. The proliferation of such images in the mass media and through migrant networks ensured that guest workers and their children knew about this graffiti even if they had not directly confronted it. Especially disturbing was that anti-Turkish graffiti was often accompanied by swastikas, which visually implied that Turks and other “foreigners” were destined to a similar fate as Jews. Amid the public reckoning with how the resurgence of neo-Nazism threatened both public order and the very project of liberal democracy itself, the Turkish-Jewish comparison threatened not only migrants but also West German society.

The so-called Turkish jokes (Türkenwitze) put migrants at further unease.Footnote 87 Reflecting the stereotype that Turks often worked in “dirty” jobs like garbage collectors, street cleaners, and construction workers, one joke questioned: “Why are some garbage cans made of glass? So that even Turks have a window to look out of.” In dehumanizing and misogynistic language, another joke went: “What is the difference between a Turkish woman and a pig? One wears a headscarf.” The most common jokes, however, made light of death and even murder. Many directly alluded to the Holocaust, particularly the murder of Jews in the gas chambers:

What is the difference between a Turk and the median on the Autobahn? You can’t drive over the median.

What is a misfortune? When a ship full of Turks sinks. What is a catastrophe? When a Turk survives.

Have you heard that Turks carry a knife all the time? Between their shoulder blades and ten centimeters deep.

Have you seen the latest microwave oven? There’s room in it for a whole family of Turks.

How many Turks fit in a Volkswagen? A hundred! Four on the seats, and the rest in the ashtray!

A trainload of Turks leaves Istanbul but arrives in Hamburg empty. How come? It came by way of Auschwitz.

The German scholar Richard Albrecht, writing at the time, interpreted these jokes as revealing the latent racism among the mainstream German population.Footnote 88 Equally important to understand, however, is the sheer impact that these hateful words had on the migrants themselves.

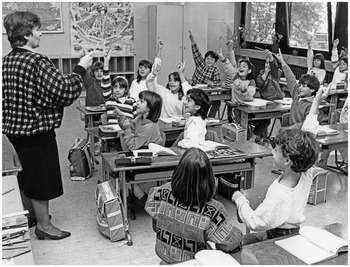

Jokes, slurs, and bullying were especially common – and traumatic – for children. Everyday contact with German classmates, teachers, and school administrators was a double-edged sword. On the one hand, many Turkish children achieved academic success, built strong relationships with their teachers and classmates, and viewed school fondly. On the other hand, schools were also sites of racist encounters that left children wavering between belonging and rejection. In one particularly blatant example of West Germans using the language of “race” and “race-mixing,” a German mother attempted to enroll her half-Turkish son in a German international school during a stay abroad, but the principal immediately rejected them, noting abruptly: “Sorry, but in our kindergarten, we only accept pure-blooded (reinrassige) children.”Footnote 89 Especially hurtful was when racism came from the mouths of their peers, who often reiterated their parents’ condemnation of Turks. When an eleven-year-old girl named Nirgül walked into her fourth-grade classroom for the first time, she was greeted with jeers. “Eww, we have another Turk,” her classmates complained, refusing to sit next to her, while one boy insisted, “I have to be a meter away from a Turk.”Footnote 90 Of course, there were instances in which German classmates attempted to intervene on behalf of their Turkish friends – but the bullies typically pressed on. “Even if you scream at them,” one German high schooler complained, “they still are not convinced … I don’t think they know that it hurts his feelings.”Footnote 91

Given the rising attention to Holocaust education in the 1980s, schools also provided a space for Turkish children to contextualize their personal experiences of racism within the longer-term continuities of Germany’s Nazi past.Footnote 92 Although they did not have personal or family connections to the Third Reich, they were able to draw parallels to their own experiences. One Turkish girl named Çiğdem, who later returned to Turkey with her parents, recalled how sitting in the classroom with German students and learning about their grandparents’ crimes proved crucial to her journey of self-discovery. While learning about the Nazis’ persecution of Jews, Çiğdem “realized that we Turks are affected exactly the same way and are next in line.” Comparing her experience to the Holocaust also provided her with a new weapon in her arsenal to fight back. When one of her elderly neighbors screamed that she was a “stinking Turk,” she became so angry that she called him a “Jew eater” (Judenfresser).Footnote 93

Turkish migrants had legitimate reason to fear that hateful words might turn into physical – or fatal – violence. The media regularly covered the concurrent rise in organized neo-Nazism and neo-Nazi violence. Their fears were heightened by the well-publicized shooting at the Twenty Five discotheque in Nuremberg, an establishment that was often frequented by foreigners and people of color. On June 24, 1982, the twenty-six-year-old West German neo-Nazi Helmut Oxner pulled out a high-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver and started shooting at people on the dancefloor. He murdered two African-American men – one a civilian, and one a military sergeant – and near fatally injured a Korean woman and a Turkish waiter. After fleeing the discotheque, he pulled out another gun and proceeded to shoot with two guns at foreigners passing by on the sidewalk. There, he murdered an Egyptian exchange student and crushed the jaw of a man from Libya. Before turning the gun on himself, Oxner shouted, “I only shoot at Turks!”Footnote 94 Oxner had been known by police: just two days before, he and another neo-Nazi had anonymously telephoned the police station, lambasting Turks and Jews as “camel drivers,” “foreigner pigs,” and “Jew pigs.”

In the weeks immediately following the shooting, leading West German newspapers emphasized the pervasiveness of anti-Turkish physical violence throughout the country, tying together smaller incidents into a narrative of rising danger. This “everyday violence,” as Die Zeit put it, was no longer exceptional: “Not a day goes by without news of bloody attacks against a minority that was once enthusiastically invited.”Footnote 95 In Hamburg, Der Spiegel reported, Turkish teachers were “terrorized” with death threats. In Berlin, two men accosted a Turkish man in the subway, remarking that “previously something like that would have been gassed.” In Munich, two other men stabbed a Turkish teenager in the throat with a broken beer bottle, shouting that he was a “foreigner pig that belongs in Dachau.” In Witten, a wall was defaced with graffiti warning: “The Jews have it behind them, the Turks still in front of them.”Footnote 96 In Frankfurt, a German man horrifically threw a three-year-old Turkish girl into a trashcan because, in his words, “the filthy people (Dreckvolk) must go.” At the core of these discussions was a central question, which struck at the heart of West Germany’s broader racial reckoning: were the culprits all neo-Nazis and skinheads, or were they also ordinary people unaffiliated with extremist groups? For Der Spiegel, the answer was clear: this violence was “in no way” perpetrated only by “organized neo-Nazis.”

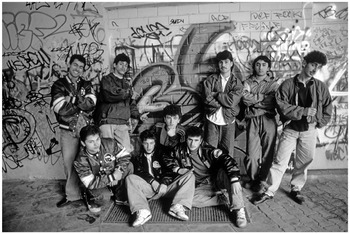

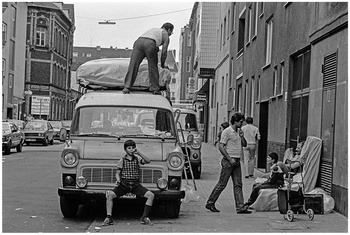

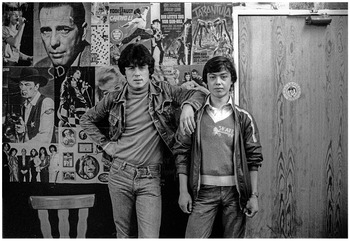

Rather than acquiesce to racist rhetoric and violence, Turks engaged in varying forms of anti-racist activism, which operated on a spectrum from peaceful protest to the formation of violent gangs. As early as the 1970s, Turks living in the slums – or what Germans denigrated as “Turkish ghettos” – banded together into gangs to defend themselves.Footnote 97 As the West German Embassy in Ankara put it in 1982, these gangs functioned as “self-protection organizations”: “I wouldn’t be surprised if the Turks began to fight back,” wrote one embassy official forebodingly, which he feared could lead to “blood vengeance” (Blutrache).Footnote 98 One of the most prominent of these gangs was the 36 Boys, founded in 1987 in West Berlin’s heavily Turkish district of Kreuzberg, often called “Little Istanbul” (Figure 4.3). In a 2005 interview, a former member of the 36 Boys named Ali explained that he joined at age twelve because he knew many of the members and craved a sense of community. Embracing African-American culture, Ali and his friends went to rap and hip-hop parties, learned how to breakdance, and sprayed graffiti art on walls.Footnote 99 But, on the darker side, Ali also recalled many nights out on the streets with his fellow gang members fighting neo-Nazis and watching his friends die from stab wounds.Footnote 100 Turkish gang violence rose in the early 1990s, as a means of defense against the onslaught of neo-Nazi attacks after reunification.Footnote 101 Although West German media coverage acknowledged the justification of self-defense, they tended to place the blame primarily on Turkish gangs themselves, even though German neo-Nazis and right-wing extremists were responsible for instigating the violence and posed a greater threat.Footnote 102

Figure 4.3 Members of the prominent Turkish gang 36 Boys in Berlin-Kreuzberg proudly stand in front of “36” graffiti, 1990.

Far more often, however, the fight against racism was peaceful. Turkish workers overwhelmingly chose the pen over the sword, lobbying their political representatives and labor union leaders. In March 1982, for example, Turkish mineworkers in Gelsenkirchen wrote a scathing letter to the president of the Industrial Union of Mining and Energy (IGBE). When reading an article in the Turkish newspaper Hürriyet, the workers were shocked that the newspaper had quoted the mine’s director as being “very satisfied with the performance of the Turks.” Appalled at the director’s seeming disingenuousness, the workers complained: “How is something like that even possible at our mine? Here we are despised and suppressed, and we suffer under Ausländerfeindlichkeit.”Footnote 103 Within the past year, four of their Turkish colleagues, including one with a disability, had been brutally beaten by Germans on the job. That year, the IGBE president also received a letter from a Turkish union member who, without using the word “race,” invoked the legacy of Nazism and worried that the past might repeat itself. Germans, he explained, viewed foreigners as a “threat to the pure German culture” and as a “problem that was waiting for its final solution (Endlösung).” Both politicians and academics, he wrote after the Heidelberg Manifesto’s publication, were striving to create “a clean world of ‘blue-eyed and blonde-haired people.’”Footnote 104

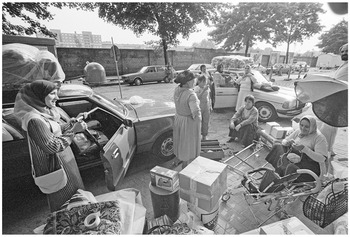

Neighborhoods and apartments were also sites of protests against discriminatory local ordinances.Footnote 105 One particularly well-publicized incident took place in the district of Merkenich in the outskirts of Cologne, where during the 1960s, Turkish migrants had built their own houses on the largely abandoned Causemannstraße. By 1981, twenty-eight families were living there, frequently receiving threatening letters from the district government commanding them to leave as part of a broader effort to gentrify the district and rid it of Turks. Overnight in August 1982, while many of these families were on vacation in Turkey, the Cologne city government sent construction workers to tear down five houses. In a flyer that circulated throughout Cologne, the migrants maintained that all they had done was attempt to make “their own homes, simple wood and stone houses, almost a small village with vegetable gardens, courtyards, and pergolas,” with places for children to play and where “men and women can maintain the sociability and hospitality they are accustomed to at home undisturbed by German landlords.” Tearing down the five houses, they asserted, was an act of Ausländerfeindlichkeit on the part of the municipal government.Footnote 106

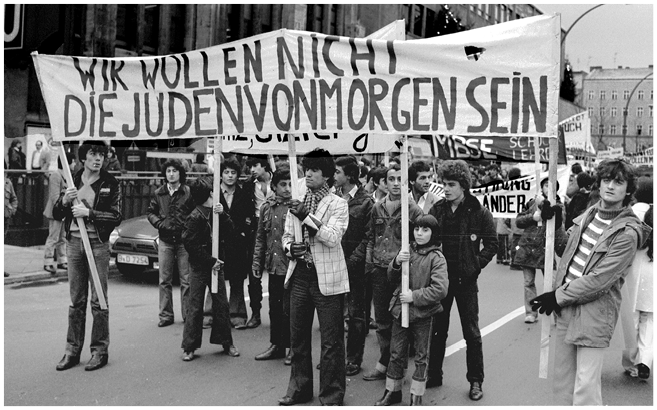

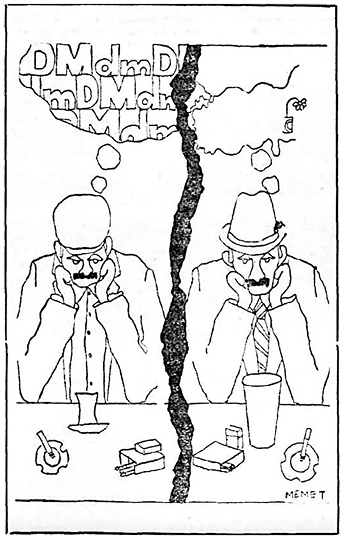

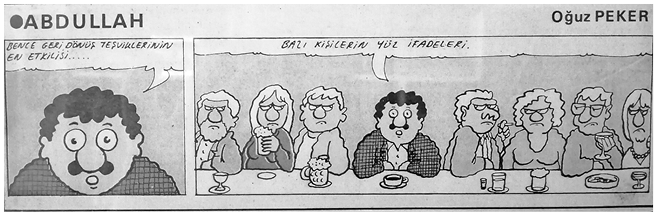

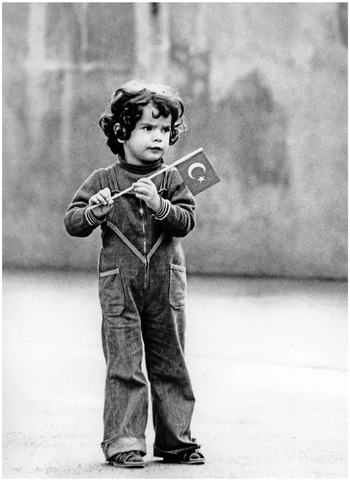

Turks also took to the streets to peacefully protest, often joined by sympathetic Germans. In November 1982, the local Protestant pastor in Gelsenkirchen worked alongside Turkish residents to organize a large “protest against Ausländerfeindlichkeit,” which attracted 500 demonstrators. This protest came in response to a spate of neo-Nazi violence that occurred in early November, the same week as the 44th anniversary of Kristallnacht. The Gelsenkirchen attack saw neo-Nazis ignite a fire at the office of the local Turkish workers association, spraypaint racist graffiti and swastikas on some two dozen storefronts owned by migrants, and send death threats to Turkish workers.”Footnote 107 The pastor defended the migrants: “They are not ‘Kanaken,’ they are not ‘pigs’… They are not ‘overrunning us … They are not ‘infiltrating’ us.”Footnote 108 He insisted that combatting Ausländerfeindlichkeit began first and foremost with Germans themselves. Germans, he cautioned, should not “bite our tongues when harmful, false words want to come out of our lips,” nor should they continue to “laugh at jokes about foreigners.” Importantly, amid the rise of Holocaust memory in the 1980s, these protests sometimes directly referenced the Holocaust, with Turks overtly comparing their situation to that of Jews during the Third Reich (Figures 4.4 and 4.5).

Figure 4.4 Young Turkish protesters march with a banner that states: “We do not want to be the Jews of tomorrow,” 1981.

Figure 4.5 Protesters somberly hold yellow Stars of David, which the Nazis forced Jews to wear, to draw a powerful visual connection between past and present persecution, 1982. Written in the stars are “asylum seeker,” “foreigner,” and “Jew,” although it is unclear whether the individuals holding the signs belong to those respective groups.

Protests of this sort, however, also revealed the fissures between Turks and Germans – or what Jennifer A. Miller has called “imperfect solidarities.”Footnote 109 Like in the Gelsenkirchen case above, protests were frequently organized by Germans, with relatively minimal input and participation from Turkish migrants. So, too, were protests often performative, with even the most well-meaning of German demonstrators taking to the streets without working to dismantle the elements of structural racism. One particularly striking example occurred in 1991 amid the wave of neo-Nazi violence after reunification in the heavily Turkish city of Duisburg. There, some two hundred people demonstrated in a silent march in the middle of a hailstorm, carrying signs with catchy slogans, such as “People eat gyros and döner kebab, so why do they try to get rid of the cook?” and “Do we only need foreigners for German garbage disposal?”Footnote 110 However, this protest was organized on the initiative of German doctors, nurses, and social workers at a local hospital without consulting any migrants, and both German and Turkish passersby appeared disinterested. In fact, one Turkish representative on the Duisburg’s Foreigner Council (Ausländerbeirat) even questioned why so few Turks were willing to participate alongside Germans.Footnote 111

Ultimately, examining Turks’ anti-racist activism reveals that – just like in matters of determining who counted as “German” – West Germans did not have a singular claim to reckoning with racism. And, just like racism itself, anti-racist activism existed on a spectrum. The case of Semra Ertan, who publicly set herself on fire in protest, is a powerful reminder not only of just how deeply racism was embedded in migrants’ psyches but also of the sheer frustration and desperation that many migrants felt. To be sure, not all migrants who engaged in forms of protest considered themselves political activists. Rather, fighting back against both structural and everyday racism – whether in workplaces, schools, or neighborhoods – was often simply a matter of everyday necessity to improve their living conditions and prevent further discriminatory acts. That some Germans leapt to Turks’ defense provides an encouraging counterpart to others’ blatant racism. Still, moments of solidarity proved fraught. When Germans defended Turks, they did so not necessarily out of sympathy for migrants, but mostly to mount a show of strength against the rising tide of right-wing extremism and neo-Nazism. Germans’ allyship thus slipped into what feminist scholar Linda Alcoff has called “the problem of speaking for others,” whereby “the practice of privileged persons speaking for or on behalf of less privileged persons has actually resulted (in many cases) in increasing and reinforcing the oppression of the group spoken for.”Footnote 112 Enjoying comfort in public space, and safe from the threat of retribution, Germans – despite their best intentions – drowned out the voices of the migrants themselves.

Turkey’s 1980 Coup, Human Rights, and Holocaust Memory

As performativity eclipsed real change, it became up to those in the home country to defend the migrants against the forces of hate. As news of a possible remigration law spread in the early 1980s, the racial reckoning echoed abroad, enflaming bilateral tensions with Turkey. The Turkish government staunchly opposed the proposed remigration law not only for policy reasons, as it blatantly contradicted Turkey’s financially based opposition to the guest workers’ return, but also as a matter of political strategy and principle. While Turkish officials did not always act in the migrants’ best interests, they envisioned themselves – at least outwardly – as the protectors of their mistreated citizens abroad. Turkish media outlets and ordinary citizens also rushed to the migrants’ defense, even though they simultaneously ostracized the migrants as “Germanized.” Generalizing all Germans as inherently racist, Turkish critics accused them of violating the migrants’ human rights and drew direct comparisons to the Nazi past: Turks were the new Jews, Schmidt was the new Hitler, and the 1980s had become the 1930s. The Holocaust thus became a usable past for Turks, one that could be deployed in debates about return migration or used, alternatively, to whitewash Turkey’s own past and present abuses against minority groups.

But this rhetoric was accompanied by a great irony: it occurred in the immediate aftermath of the September 12, 1980, military coup, when Turkey’s authoritarian government became the target of international scorn for committing egregious human rights violations against political dissidents, Kurds, and other minority populations. The coup was a major turning point in Turkey’s relationship with Europe, as it brought Turkey’s status as a “European” country into question and strained its relations with the EEC. Just three weeks after the coup, both West Germany and France introduced obligatory visas for Turkish citizens, and other EEC countries followed suit.Footnote 113 The West German government under Chancellor Helmut Schmidt found itself in a particularly tricky situation and had to tread lightly. For West Germany, many issues were at stake: Turkey was a crucial NATO ally against the Soviet Union, West Germany was the second largest provider of military and economic aid to Turkey, and Turkey’s cooperation on the question of guest workers’ return migration was paramount.Footnote 114 Moreover, the coup government’s heightened emphasis on Turkish nationalism and militarism contradicted West Germans’ growing wariness of nationalism and their turn toward a “postnational” identity rooted in broader ties to Europe. But Schmidt’s government also had to balance its diplomatic support for Turkey with domestic criticism. SPD parliamentarians expressed concerns that Turkey might “abuse” West German military aid to “suppress” the Kurdish minority and Turkish dissidents. In solidarity with Turkish and Kurdish activists, West German students, journalists, churches, trade unions, and migrant advocacy organizations complained that the West German government was “dismissing” or “watering down” Turkey’s abuses.Footnote 115 Still, even the mild reproach of Turkey by Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher “clearly offended the Turkish leaders.”Footnote 116

The 1980 military coup alarmed West German policymakers not only because of the authoritarian government and blatant human rights violations, but also because the resulting rise in asylum seekers posed a further impediment to solving the domestic “Turkish problem.” They argued that granting asylum to Turkish citizens would not only result in far greater numbers of “Islamic,” “Asiatic,” and “Oriental” people coming to West German, but would also create a “Kurdish minority problem” by transferring Turkey’s “ethnic tensions” to West Germany.Footnote 117 As a result, West Germany continued to label Turkey a “safe country,” excluded Kurds and Yazidis from its narrow definition of “political persecution,” and accepted only 2 percent of asylum seekers from Turkey between January 1979 and August 1983.Footnote 118 Policymakers also feared that granting asylum to dissidents would heighten political violence among migrants. Particularly worrisome were the Grey Wolves (Bozkurtlar), a militant, right-wing extremist, pan-Turkist organization tied to Turkey’s Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) founded in 1969. In the words of Der Spiegel, the MHP was “racist” and “fascist,” and its founder Alparslan Türkeş was a “Hitler admirer” who “dreams of a new Greater Turkish Empire.”Footnote 119 The West German Interior Ministry did not hesitate to describe Türkeş’s “true goals” in terms of Nazism: seizing power “exactly as the Nazis,” implementing “National Socialist doctrine” in Turkey through “oppressive measures,” “liquidating” all ethnic minorities, and uniting all Turks on the Earth under the principle of ‘One People, One Empire’ (ein Volk, ein Reich).”Footnote 120 Although Turkey’s post-coup government outlawed the MHP and imprisoned Türkeş, many West Germans continued to associate the Grey Wolves with Turkish authoritarianism and worried that extremism lurked among guest workers.

The situation was further compounded by Turkey’s looming full membership in the EEC, which was planned for 1986 but never materialized. Just three days after the coup, the EEC declared that discussions about Turkey’s full membership could only continue if the military government “quickly reinstated democratic institutions and respected human rights.”Footnote 121 Yet it soon became clear that Turkey was failing to “announce a precise timeline” for returning to democracy and that discussions about full membership would therefore be “frozen.”Footnote 122 With the highest proportion of Turkish immigrants, West Germany had the largest stake in Turkey’s membership – particularly regarding the provision that citizens of member states be granted freedom of mobility. Already grappling with how to limit the number of Turks allowed to enter the country, West German officials desperately sought to twist the terms of the EEC’s discussions such that Turkey could become a member without receiving freedom of mobility. As one internal memorandum on the issue stated emphatically, underlined for emphasis, “We must permanently exclude Turks from having unlimited access to our labor market!”Footnote 123 Behind closed doors, the Belgian and Danish governments, which also had sizable Turkish populations, agreed. West Germans thus weaponized Turkey’s authoritarianism and human rights violations to express their concerns about freedom of mobility for unwanted Turkish citizens.