1.1 Resolution of Shareholder Disputes in a Small Private Company

The majority of companies registered in the Hong Kong Company Registry are, in fact, closely held corporations whose shares are not publicly traded.Footnote 1 Clearly, these small quasi-partnership types of private limited companies are playing an important role in the Hong Kong economy, as about 60 per cent of the Hong Kong population is employed by these entities.Footnote 2 Although the strength of personal and/or family ties offers real benefits for shareholders to work closely together in a privately owned business, minority shareholders in particular are vulnerable to the opportunistic conduct of majority shareholders. Therefore, minority shareholder disputes are of concern primarily to private companies with management ownership concentrated in the hands of a small group of family members.

In general, the family business model can be viewed as the ‘powerhouse’ that not only generates wealth and economic well-being, but also strengthens the intimacy of family ties that support the ongoing operation of a family business.Footnote 3 These blood ties may consequently produce superior performance of a business enterprise.Footnote 4 However, the informal organizational structure of small private companies, coupled with the doctrine of majority rules, makes it possible for those who control the majority of shares in the company to employ a variety of squeeze-out techniques (such as exclusion from management, dilution of minority shareholding with an improper motive, excessive remuneration, misapplication of company assets and similar practices), which are unfairly prejudicial to the interests of minority shareholders who hold fewer shares in the company.Footnote 5

Corporate conflicts can be destructive when multiple disputes involving the desire for power and wealth and other personal feelings remain unresolved.Footnote 6 In particular, Corporate conflicts involve ‘deep-rooted issues which are seen as non-negotiable’, whereas shareholder disputes are considered specific disagreements relating to the question of rights or interests in which disputing parties proceed through a range of dispute resolution methods, such as adjudication, mediation, avoidance, self-help and so on.Footnote 7 In the corporate environment, the self-interested desire to increase power or wealth could further lead to the breakdown of the personal relationships between shareholders and result in deep-rooted conflicts in which issues are non-negotiable.Footnote 8 In general, the most common types of behavioural patterns associated with distinctive characteristics of shareholder disputes in a small, closely held company such as marital discord,Footnote 9 sibling rivalryFootnote 10 and so on could disrupt the family business.

For instance, disputes can arise over the power to control business activities among members of the second generation after the passing of the founder of a family business.Footnote 11 The younger siblings may take an entrenched position with regard to either retaliation against the first-born for receiving preferential treatment or disagreement about the company’s strategies. The younger siblings could form an alliance with other senior family members to usurp the first-born’s authority by using squeeze-out techniques available under the majority rule to diminish the role or the stake of the first-born in the company. In this scenario, an unresolved dispute among the siblings and other family members within the company escalates into a full-blown crisis that would jeopardize the survival of the family business.

Clearly, there could be various possible underlying factors in shareholder disputes (such as unresolved issues from the past, sibling rivalry, interpersonal relationships, etc.) inviting a general state of hostility between members in a small private company (i.e., corporate conflicts). Corporate conflicts from which shareholder disputes emerge are undesirable, as these could eventually lead to the irretrievable breakdown in relations in a small private company (such as deadlock). To prevent the relational breakdown due to unresolved personal conflicts among shareholders in a small and closely held corporation, both the Hong Kong government and the Judiciary should aspire to developing a sophisticated dispute resolution system that offers a range of formal and informal dispute resolution processes for local businesspersons and their lawyers to choose from.Footnote 12 Further, such a system could reinforce Hong Kong’ s competitiveness and attractiveness as a global financial centre.

Over the past decades, the Hong Kong government has sought to emulate the United Kingdom’s corporate legal framework by amending its Companies Ordinance virtually step-by-step tracking many of the reforms in the United Kingdom.Footnote 13 Court-based shareholder proceedings have been generally regarded as the most appropriate ways of dealing with shareholder disputes where the majority shareholders are exercising abusive power to gain outright control of the company, depriving the company minority of their rights and interests.Footnote 14 Minority shareholders submit their disputes for resolution by a third-party judge, thereby surrendering a degree of control over the proceedings under this traditional, litigation-based approach to resolving minority shareholder disputes.Footnote 15 An independent neutral judge has the authority to impose an authoritative decision on the parties based on evaluations of the pre-existing legal principles and the legal rights of the disputing parties. Generally speaking, there are three underlying reasons for the attractiveness of court-based shareholder proceedings under the statutory unfair prejudice provisions.

First, the statutory unfair prejudice remedy was initially introduced as an alternative to the just and equitable winding-up remedy in Hong Kong.Footnote 16 This provision makes it easier for a minority shareholder to bring an action to the court in a case in which the nature of the complaint is related to the infringement of personal rights rather than a breach of duty to, or other misconducts actionable by, the company.Footnote 17

In Hong Kong, the vast majority of companies are small and medium-sized enterprises.Footnote 18 They are often formed on the basis of mutual trust originating from close and personal relationships between members.Footnote 19 A member in a small private enterprise typically places great reliance on the understandings that form the basis on which the company was formed to actively participate in the business affairs.Footnote 20 These understandings, however, are in fact not truly reflected in the articles or any other written agreements. The character of a quasi-partnership company was reflected in a seminal case, Ebrahimi v. Westbourne Galleries Ltd, where Lord Wilberforce stated thatFootnote 21

The words [“just and equitable”] are a recognition of the fact that a limited company is more than a mere judicial entity, with a personality in law of its own: that there is room in company law for recognition in fact that behind it, or amongst it, there are individuals, with rights, expectations and obligations inter se which are not necessarily submerged in the company structure.

On that basis, it is not uncommon that the statutory unfair prejudice remedy is usually sought by aggrieved shareholders in private companies, as the scope for finding expectations which are supplementary to a member’s strict legal rights is obviously greater in small quasi-partnership types of private limited companies.Footnote 22

Second, the court’s discretionary power in granting relief under the unfair prejudice provisions has been substantially enhanced through the Companies (Amendment) Bill 2004 and more recently the new Companies Ordinance (Cap. 622) which took effect on 3 March 2014.Footnote 23 Specifically, Section 725(2)(b) of the new Companies Ordinance expands the court’s discretion to grant corporate relief in an unfair prejudice petition.Footnote 24 This provision can be viewed as the most remarkable improvement, as it provides greater clarity and certainty with regard to the court’s power to grant damages in the event of unfair prejudice.Footnote 25 Also, the provision of Section 168A of the former Companies Ordinance (Cap. 32) is modified to be in line with the corresponding provisions in the UK Companies Act 2006, which extend the scope of unfair prejudice remedy to cover ‘proposed acts or omissions’.Footnote 26

Third, the new statutory unfair prejudice remedy has proved to be more effective than the statutory derivative actions.Footnote 27 Remedies under the unfair prejudice provisions are much wider than both the common law and statutory derivative actions.Footnote 28 A list of specific remedies is set out in the unfair prejudice provision (such as the court’s power to grant damages in circumstances of unfair prejudice, or a share purchase order for a buyout of the minority shareholders, etc.). This provision empowers the court to make any order that it thinks fit for giving relief. In addition, an unfair prejudice claim is generally perceived to be more attractive, as shareholders would not necessarily need to go through the expenses and uncertainties of a leave application.Footnote 29

However, Hong Kong’s corporate legal framework is largely influenced by its UK counterpart, as it was a former British colony.Footnote 30 The English common law adversarial system maintains its influence over the manner in which evidence is to be adduced by the parties during the course of unfair prejudice proceedings. Shareholder litigation remains costly, as the complexity of both the evidentiary and procedural rules may eventually lead to a greater reliance on lawyers to represent a lay businessperson who is without any litigation experience in court.Footnote 31 Thus, the courts would have to serve as the last resort for minority shareholders whose legal or equitable rights or interests have been violated by those who control the majority of shares in a company.

Indeed, shareholders react to disputes not only through public court adjudicative process for settlement, but also through various techniques, including revenge, self-help, avoidance, negotiation, mediation and similar methods for handling disputes.Footnote 32 Shareholder disputes involve both legal and non-legal elements that can influence not only the outcome of the case, but also the choice of a particular process.Footnote 33 Every procedure has its own characteristics. Shareholders and their lawyers can decide which dispute resolution methods fit their needs. In general, the basic processes for settling shareholder disputes are listed as follows:

Negotiation: A quasi-partnership company enables shareholders to explore the possibility of early settlement by negotiating the terms of the buyout before trial.Footnote 34

Facilitative mediation: This process opens the channel of communication that encourages the parties to maximize their chances of maintaining a good relationship in the future.Footnote 35

Collaboration and collaborative practice: Like mediation, this process is a ‘solution-oriented and interest-based process’ that involves identification and selection of options and alternatives maximizing the interests of all parties.Footnote 36 However, the most obvious difference between mediation and collaborative approach is ‘the dynamics of the process’.Footnote 37 The collaborative model enables the parties to work with a team of collaborative lawyers and other experts (such as psychologists, accountants and financial planners) in achieving mutually a satisfactory settlement.Footnote 38 The collaborative process could also be used in resolving shareholder disputes as this process offers not only individual support to each client.Footnote 39 In addition, the multidisciplinary nature of the collaborative practice offers specialized support from professionals in helping the parties to deal with sensitive and emotional issues.

Mini-trial: Shareholders may strongly prefer a mini-trial if they want to minimize the costs associated with the lengthy investigation of the unfair prejudice conducts during the court litigation process. A mini-trial is generally considered a suitable alternative means of resolving shareholder disputes where shareholders seek to explore the possibility of early settlement. In the mini-trial, a neutral third party can make an early assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of each side’s case and the likely outcome of litigation.Footnote 40

Expert determination: Expert determination is a common mode of informal dispute resolution process used to resolve shareholder disputes.Footnote 41 In expert determination, a neutral third party is appointed by the parties who possesses sufficient technical expertise in the subject matter of the disputes to bring to bear in the making of decisions. The nature of expert determination makes it particularly suitable to solving unfair prejudice cases where the only outstanding issue is a technical matter such as the valuation of minority’s shareholdings in the event of a buyout.Footnote 42

Arbitration: This process has generally been preferred over litigation for resolving cross-border shareholder disputes as the enforcement of arbitration agreements is secured by the most important international treaty, namely, the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Award (the New York Convention 1958).Footnote 43

Adjudication: A court adjudicative process is particularly suitable where both parties have the desire to discontinue their business relationship and to achieve a clean break.Footnote 44

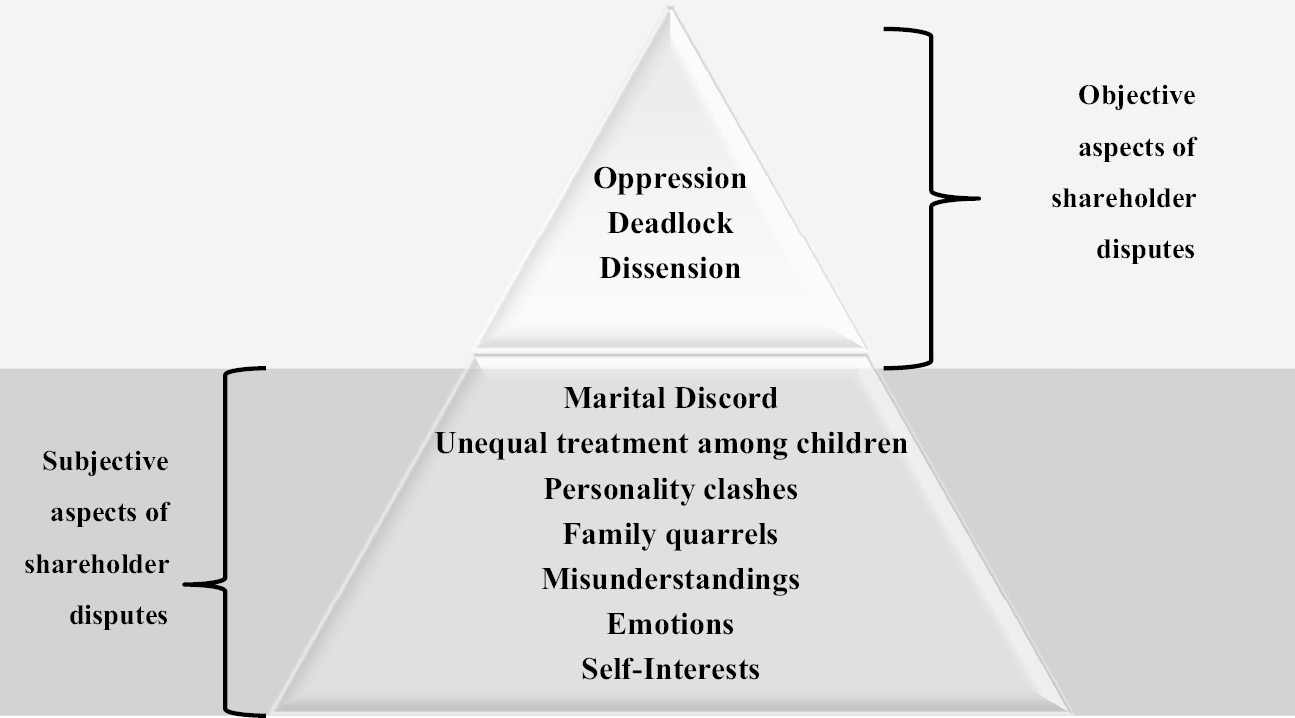

Obviously, court-based shareholder proceedings are by no mean the most superior settlement procedures. First, the underlying causes of shareholder disputes including misunderstandings, feelings and personality clashes are often overlooked or ignored by either the court or the corporate lawyers. These subjective aspects of shareholder disputes are, in fact, located at the submerged part of the iceberg, and it is not always a straightforward matter for the court or lawyers to identify one factor or a combination of factors which contribute to the breakdown of a quasi-partnership type company (see Figure 1.1).Footnote 45

Figure 1.1 The iceberg of disputes between shareholders in a family-owned business.

In general, the role of the court is not to investigate who or what caused the breakdown of personal relationships between shareholders.Footnote 46 Instead, the focal point of the court’s enquiry in determining whether a shareholder has been prejudiced in an unfair manner is the effect of the opportunistic conduct of the majority and not the nature of the conducts that are the subject of the complaint.Footnote 47 Judges often miss the true cause of a dispute (such as personality clashes) as they concentrate on the ‘objective aspects’ of shareholder disputes and the application of law and equity in determining whether the conduct complained about is unfairly prejudicial to the interests of minority shareholders. In general, the objective aspects of shareholder disputes can be classified as follows:Footnote 48

Dissension: Disputes between the shareholders inter se may lead to dissension, where a minority shareholder might either dissatisfy or disagree with the corporate policies which management is pursuing.Footnote 49

Oppression: A dissident shareholder may file a petition to the court alleging that the conduct of the majority shareholders was unfairly prejudicial to the interests of the petitioners.Footnote 50

Deadlock: Dissension may subsequently result in serious disagreement in a company, and this may be harmful to the continuation of an ongoing business, as it could lead to the drastic consequence of a winding-up.Footnote 51

The court’s approach to the scope of unfair prejudice provision affects significantly lawyers’ approaches towards handling of shareholder disputes. The true causes of shareholder disputes, such as misunderstandings, fears and personal feelings, are rarely discussed between lawyers and their clients.Footnote 52 Consequently, court adjudicative process focuses specifically on a faction of disputing issues, regardless of the submerged part of those underlying facts that contribute to shareholder disputes.

Second, Lord Hoffmann’s reasoning in O’Neill v. Phillips has been expressly adopted and applied by the Hong Kong courts, which recognize only the parties’ expectations arising either from formal contractual agreements or informal understandings binding under the general principles of law and equity.Footnote 53 An alleged unfairly prejudicial conduct is assessed objectively not only on whether an honest and reasonable man would regard the conduct complained is unfairly prejudicial to the interests of the members generally or of some part of its members in the particular business context.Footnote 54 In addition, the content of ‘unfairness’ is to be judged by reference to established equitable rules (such as the doctrine of good faith) instead of allowing vague notions of unfairness to be used in creating commercial uncertainty as to the costs and length of the proceedings.Footnote 55 This approach inevitably limits the concept of unfairness, as the type of the petitioner’s legitimate expectations is usually confined within the ambit of the statutory unfair prejudice remedy as delineated in O’Neill v. Phillips, on the basis of the recognition either that the expectations formed part of the implied terms of the agreements or understandings when a person becomes a member or that they arise out of the exercise of strict legal rights in a manner which equity would regard as contrary to good faith.Footnote 56

Although the concept of unfairness has been narrowly construed, the categories of unfairly prejudicial conduct are not closed.Footnote 57 This is particularly true as the court is entitled to exercise its discretionary power in the statutory unfair prejudice jurisdiction to elucidate the equitable principles and considerations, including the imposition of equitable constraints to estop the majority from exercising a strict legal right which is unfairly prejudicial to the interests of the members generally or of some part of its members.Footnote 58 Unfair prejudice proceedings can still be lengthy and potentially expensive. Specifically, in order to establish a good arguable case that the alleged conduct is unfairly prejudicial, the petitioners still have to produce detailed accounts of the history of the company and show that the parties have come to some other specific arrangements or promises which are not reflected in the articles and the provisions of the Ordinance. On such a basis, it seems appropriate to consider a broad array of innovative dispute resolution techniques that may help to reduce the burgeoning caseload on the court.Footnote 59

Generally speaking, the term alternative dispute resolution (ADR) is used interchangeably with the term ‘innovative dispute resolution’, and it is defined as an alternative method of settling disputes which are separated from court adjudication.Footnote 60 ADR includes a broad range of informal non-litigious forms of dispute resolution processes, including but not limited to arbitration, mediation, expert determination, early neutral evaluation, mini-trial, hybrid processes (such as the combination of mediation and arbitration) and similar.Footnote 61 Each of these informal out-of-court processes can be ranked in terms of the degree of formality (flexibility/rigidity) and the level of control of the processes across the spectrum. These informal out-of-court processes place efficiency, privacy, consent and individual participation above strict observance of legal rules and principles developed either by the court or as legislative enactments. As Hwang indicates, it is generally accepted that arbitration and other non-judicial methods are particularly suitable for the resolution of private company shareholder disputes.Footnote 62

At present, the key initiatives to promote the greater use of ADR to resolve shareholder disputes include the development of a voluntary court-connected ADR scheme for shareholder disputes initiated in 2009Footnote 63 and the reform of the statutory unfair prejudice provisions which took effect on 3 March 2014.Footnote 64 The new court rules, judicial directives on ADR and a new set of specific procedural rules for unfair prejudice applications have been introduced that confer specific case management powers on the courts to encourage earlier settlement of disputes and to monitor the preparation of cases for trial.Footnote 65 Court-connected mediation becomes an integral part of modern case management systems as judges have to carry out their duties to actively promote the greater use of mediation in resolving shareholder disputes.Footnote 66 Mediation is now recognized as the primary ADR process used for the reform of the law and procedures relating to unfair prejudice proceedings.Footnote 67 Clearly, the Hong Kong Judiciary and the Hong Kong government are considered to be the key role-players in promoting and encouraging the greater use of private extrajudicial processes for resolving shareholder disputes.

The Civil Justice Reform (CJR) in Hong Kong represents a major and innovative shift from the traditional, litigation-centred approach to resolving disputes and to move towards a regime which recognizes the proper use of alternative methods to resolve disputes. However, it is uncertain whether the effects of these ADR initiatives have achieved the intended goals of extrajudicial processes being perceived as more attractive and acceptable approaches to resolving shareholder disputes. In particular, the concern is not only that the widespread use of mediation as the predominant means to resolve shareholder disputes may exacerbate imbalance of power between the majority and minority shareholders in a closely held corporation.Footnote 68 An additional consideration is that the majority shareholders may be reluctant to settle or compromise at the mediation stage, as they believe that they would win the case.Footnote 69

Given the limitations of mediation and other alternative processes in resolving shareholder disputes, a balance must be struck between the right of access to the courts and the need for the maintenance of public confidence in using ADR processes to resolve shareholder disputes. This raises deeper questions about the extent to which innovative dispute resolution techniques are introduced as part of the legal framework for the resolution of shareholder disputes, and equally important, about the extent of understanding and awareness of innovative dispute resolution methods among the local legal professions.

Against the background of a new disputing landscape of Hong Kong, this book seeks to develop a theoretical framework in analysing the key stages of institutionalization that enhance the legitimacy of informal out-of-court processes for the resolution of shareholder disputes. In this context, ‘institutionalization’ refers to a process by which certain practices (such as mediation) have acquired legitimacy through their link to a broader cultural framework of beliefs or a set of rules or norms that most people support and will therefore endorse the practices.Footnote 70 Institutionalization is directly linked with legitimacy or acceptance, which provides a social basis in which certain practices are deemed desirable, proper or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, rules, values and beliefs.Footnote 71 The degree of institutionalization can then be measured in terms of three main types of legitimacy: pragmatic, moral and cultural-cogitative legitimacy.Footnote 72 Thus, the implications of the transition from the initial phase of ADR development to a more sophisticated stage in which extrajudicial processes would generally be perceived as preferred vehicles to resolve shareholders disputes can be understood in the conception of a relationship between the types of legitimacy derived from the key stages of institutionalization and the types of institutional pressures exerted by legislative mandates, the court system and the critical role of lawyers in constructing a new paradigm for dispute resolution.

Previous sociolegal academics, however, have not examined the key stages of institutionalization involved in producing legitimacy for the use of ADR for shareholder disputes in Hong Kong. In particular, scholars are less concerned with how the involvement of lawyers and the combined set of policy instruments could support the institutionalization process for ADR development.Footnote 73 Others analyse the concept of the institutionalization process in a narrow sense, as only one type of regulative legitimacy (such as court rules and specific legislations) is normally considered the most desirable method of institutionalizing the significant use of extrajudicial processes to resolve civil disputes.Footnote 74 There has been relatively little focus on the specific interest regarding the interaction of a set of legal and non-legal instruments which affect the attitudes of Hong Kong lawyers to promote the greater use of ADR for shareholder disputes. This book makes three contributions towards the development of a theoretical framework for evaluating the current ADR initiatives for shareholder disputes, particularly judicial policy on ADR and the legislative policy on the reform of unfair prejudice provisions in Hong Kong.

First, the literature about Hong Kong lawyers’ attitudes towards the use of ADR for shareholder disputes following the implementation of the CJR in April 2009 is neither very big nor particularly rich. This evaluation would aid the Hong Kong Judiciary to refine its policy strategies for achieving the target of greater responsiveness of lawyers to a new disputing climate by endorsing more pragmatic and effective approaches to resolving shareholder disputes.

Second, this book attempts to address the unresolved problem about the degree to which ADR has been institutionalized by the Hong Kong Judiciary as a means of altering lawyers’ traditional and litigation-centred approach to resolving shareholder disputes. To date, no prior empirical research has completely examined the relationship between the legitimacy of ADR practices within the legal environment and the spread of ADR practices in the Hong Kong context.

Last but not least, this book provides the first empirical analysis of the potential impact on the reform of the civil process in 2009, which may change Hong Kong lawyers’ attitudes towards the use of ADR for shareholder disputes.Footnote 75 This analysis helps to determine the spread of ADR practices within the two branches of the Hong Kong legal profession.

The following section applies the theory of sociological institutionalism as a lens through which to analyse how the institutionalization process actually unfolds in a way such that ADR can secure legitimacy through the supportive role of the legal professions and a range of policy instruments developed by the government and the Judiciary.

1.2 Arguments Development: Institutionalizing and Legitimizing ADR Policy in Shareholder Disputes

The book attempts to build on the work in sociolegal theory and sociological institutionalism seeking to establish a theoretical framework to examine the key stages of institutionalization that may secure the legitimacy of ADR for the resolution of shareholder disputes in Hong Kong. New institutional theory from sociology thus offers a useful model in analysing how ADR practices are evolving through the three sequential stages: (1) pre-institutionalization, (2) semi-institutionalization and (3) full institutionalization.Footnote 76 Institutionalization is defined as a process by which procedural innovations acquire legitimacy and ultimately become ‘taken-for-granted’ dispute resolution processes within the local business and legal professional communities.Footnote 77 Institutionalization constitutes a social basis from which legitimacy stems from the rules or other social beliefs.Footnote 78 In general, institutionalization involves the integration of procedural innovations into sources of reproduction, usually existing ones such as law, the legal professional codes of conduct and similar.Footnote 79 As such, innovative dispute resolution practices (such as mediation) would then be highly institutionalized and perpetuated over time if these practices are reproduced by persons who ‘repeatedly (re)mobilize and (re)mobilize in historical processes’ (such as law, the professions, identity categories and patterns in the life course).Footnote 80 The utility and benefits of using non-litigation modes of dispute resolution for shareholder disputes would not be questioned or challenged by the local business and legal professional communities if ADR practices are highly institutionalized.

However, it is uncertain whether mediation and other alternative processes have acquired legitimacy as fair and desirable procedures for resolving shareholder disputes within the local business and professional communities. As the former Secretary for Justice of Hong Kong Wong Yan-lun noted, this is particularly true given that mediation has not yet earned its legitimacy within the local business and legal professional communities as compared with other jurisdictions.Footnote 81 Similarly, Ms Elsie Leung Oi-sie noted that there are barriers to the development of mediation in Hong Kong, as the general public has many misconceptions about mediation’s function and outcomes when compared with the normal judicial process.Footnote 82 One possible reason for this may be attributable to lawyers’ scepticism about the procedural fairness in the mediation process. Most notably, the process of mediation may be open to abuse by unscrupulous parties who use mediation as a tactical ploy to discover information about the strengths and weaknesses of the other side’s case in subsequent litigation process.Footnote 83 Apart from that, it has been suggested that many litigants and their legal representatives seek to avoid an adverse costs order and other consequences of failure to mediate by simply going through the mediation process with no intention to attempt settlement.Footnote 84

Clearly, the company law, civil procedure rules and a set of directives on mediation issued by the Judiciary do not simply perform a symbolic function, providing a set of established rules to either encourage or discourage parties to behave in a desired manner.Footnote 85 An actor conforms to established practices not because such practices are backed by the coercive force of the state, but because they are recognized as a set of institutionalized and binding rules within the local community.Footnote 86 This reveals that laws can be considered as viable ‘instruments of social engineering’ that affect the attitudes of the people to comply voluntarily with certain practices.Footnote 87 On that basis, practice directions, court rules and the new corporate legislation can be considered as effective instruments to shape policy development on ADR for the resolution of shareholder disputes in Hong Kong. In other words, informal out-of-court process has generally been accepted as a legitimate means of resolving shareholder disputes through the court rules, practice directions and the corporate legislation.

In fact, ADR is underused if its potential benefits are not as widely known as they should be among the local businesspeople and legal professions.Footnote 88 Previous empirical studies on corporate-related dispute resolution illustrate that business enterprises were generally positive about their experience with out-of-court processes because these processes are generally viewed as flexible techniques for efficiently and effectively settling disputes.Footnote 89 It follows that the attitude or motivation of businesspeople to engage in ADR processes can affect the overall likelihood of success of the ADR initiatives for shareholder disputes, as they are the end users of ADR processes.

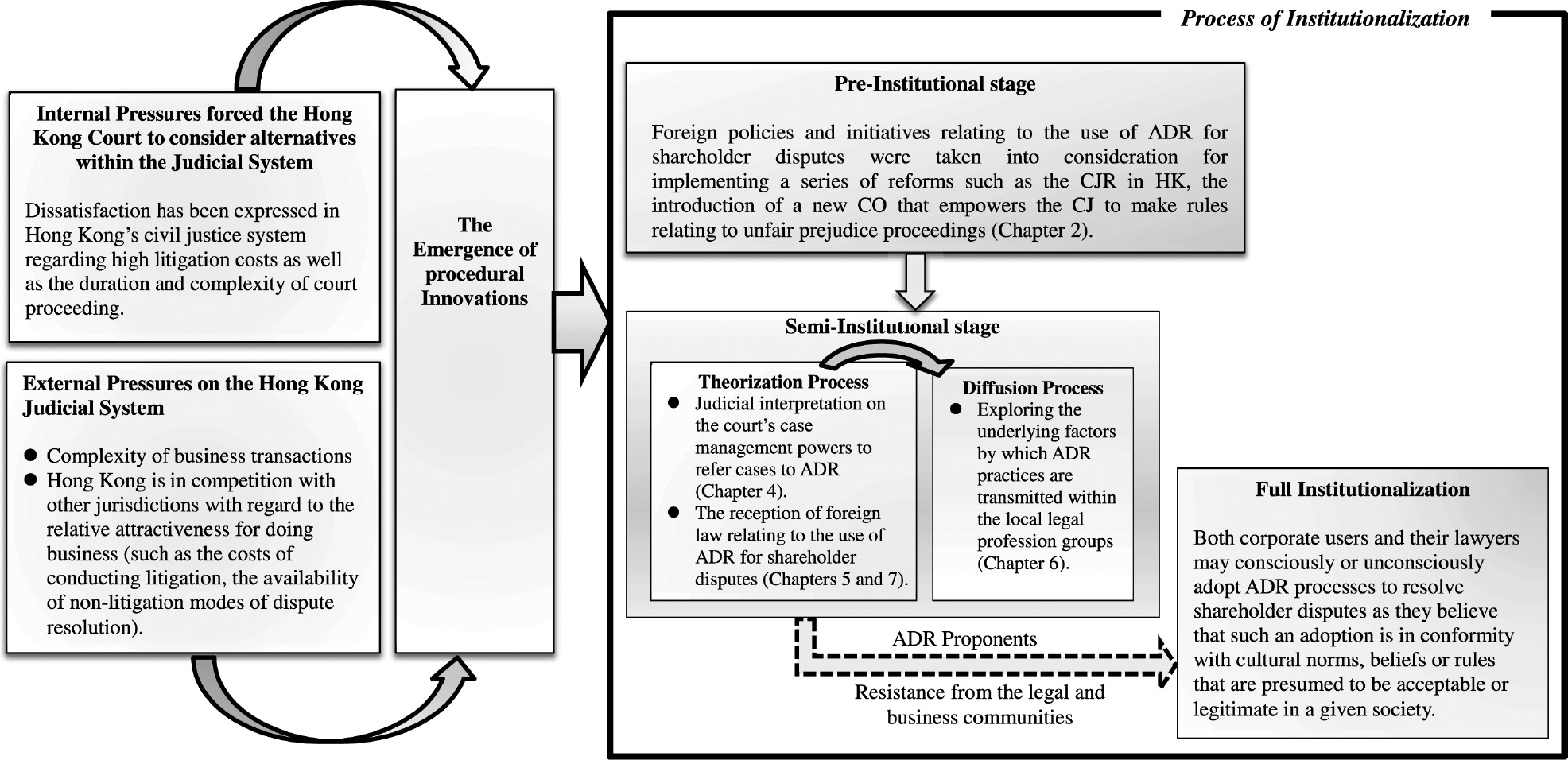

However, it cannot be ignored that the legal professions are capable of performing special roles in legitimizing the greater use of ADR within the statutory unfair prejudice regime. This argument rests on the assumption that the legal professions occupy dominant positions in the field to take control over the arrangements in ADR schemes introduced by the Judiciary and to influence the pace of promoting ADR in Hong Kong.Footnote 90 The degree to which the legal professions would support the institutionalization process of ADR for the resolution of shareholder disputes depends on how a variety of policy options are transmitted within the legal field.Footnote 91 Professional networks are effective for spreading peer influence and reinforcing the wide dissemination of ADR practices.Footnote 92 The more the information about the benefits of using ADR to resolve shareholder disputes is transmitted through the legal professional networks, the stronger the degree of institutionalization of ADR practices.Footnote 93 This analysis is in parallel to the institutional view that that full institutionalization of a given practice likely depends on the ‘conjoint effects of relatively low resistance by opposing groups, continued cultural support and promotion by advocacy groups’.Footnote 94 On that basis, institutional theory sheds light on how institutionalization actually unfolds in a way that ADR can secure legitimacy through a range of policy instruments and the role of the legal professions (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Institutionalization of ADR policy for shareholder disputes in Hong Kong.

Note: This model builds on the following literature: Tolbert and Zucker, ‘Studying Organization’, 173–178 and Greenwood et al., ‘Theorizing Change’, 59–61

As a whole, institutionalization is first triggered by ADR policy in responding to the pressures not only within the local court system, but also those of interstate competition with regard to the relative attractiveness of doing business (such as the costs of conducting litigation, the availability of non-litigation modes of dispute resolution and similar).Footnote 95 These pressures eventually become burdens on the courts to allocate judicial resources effectively that meet the needs and expectations of the disputants. The introduction of ADR into the Hong Kong courts is partly a response to remove the enormous pressure on the court dockets.Footnote 96 Although both the Hong Kong government and the Hong Kong Judiciary have provided supportive and practical steps to institutionalize ADR practices for shareholder disputes in recent years, Hong Kong is now somewhere between the stage of semi-institutionalization and the stage of full institutionalization.

It is certainly true that the utility and benefits of using informal out-of-court processes (such as mediation) to resolve shareholder disputes are more vulnerable to challenge by ADR’s opponents. There is an appreciable literature criticizing that private extrajudicial means can (1) reinforce the power imbalance between the parties; (2) promote law without justice; (3) heighten the risks of prejudice when the issue to be adjudicated touches a sensitive or intimate area such as, for example, housing or cultural-based conduct; and (4) neutralize conflicts by setting up mandatory referral of cases to ADR within the court system.Footnote 97

The critique of ADR undermines the assertion made by ADR’s proponents that informal out-of-court processes are especially beneficial to those minority shareholders who are either unable to fund the litigation or weary of using adversarial approaches to resolving intra-close corporate disputes.Footnote 98 On that basis, it is imperative to consider how the policy objectives of introducing extrajudicial processes into the statutory unfair prejudice regime would be refined and evolve through policy learning and adaption.Footnote 99 This raises the question of how the development of a broad range of policy instruments and the influence of the legal professions could ultimately increase the institutionalization process of ADR for the resolution of shareholder disputes in Hong Kong.Footnote 100

This book, by examining the recent development and growth of ADR for shareholder disputes in Hong Kong, finds that mediation and other alternative processes have not yet been fully institutionalized as preferred approaches to resolving shareholder disputes. On that basis, this book argues that the success of ADR initiatives for shareholder disputes depends not only on the efforts of the Judiciary and the government to devise a broad range of policy instruments in supporting the institutionalization process, but also on the critical role of lawyers in legitimizing the use of ADR.

First, both the court rules and a set of directives on mediation improve the legitimacy of the judicial institutions to promote the greater use of ADR within the local business community and legal professions in Hong Kong. This is particularly true, as the legitimacy of both the civil procedure rules and a set of ADR referral directions issued by the Judiciary derived not only purely from the authority but also from the endorsement of a powerful group of local businessmen.Footnote 101 One plausible line of reasoning of this is that both the court rules and case management directions on mediation are designed in conformity with the objectives of the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (the Basic Law) in preserving the existing private market-orientated legal system.Footnote 102

Law and society theorists such as Friedman and Cotterrell note that judges are statutorily bound to interpret the rules in light of a set of governing principles which were established or enacted by an authoritative body (such as the legislative body).Footnote 103 Clearly, if the law is designed in accordance with the societal necessities that gained support from a group of powerful actors, judges are more willing to follow a legalistic approach to articulating reasons as the law meets the social demands.Footnote 104 Hong Kong judges are accordingly more willing to apply rules in a manner which is consistent with ADR goals if these objectives are consistent with social norms underpinning the cultural rules of a given society, which emphasize the importance of safeguarding the free operation of business and the right of access to the courts.Footnote 105

Second, the new statutory unfair prejudice regime being introduced in the 2014 corporate legislation is a ‘relatively self-contained social system’ that accommodates the existence of ADR for the resolution of shareholder disputes.Footnote 106 On the one hand, the statutory unfair prejudice provision remains relatively autonomous from the political sphere, as it captures the interest of private enterprises for safeguarding the free operation of business affairs through contractual mechanisms.Footnote 107 On the other hand, the law remains relatively autonomous from the judicial sphere, as ethical considerations are generally taken by the court in articulating public values in the constitution.Footnote 108 Thus, the court will not make any order to compel the parties to resort to ADR in lieu of traditional court litigation processes for shareholder disputes.

Third, the legal professions serve as ADR advocates or agents of legitimacy supporting the development of ADR policy in Hong Kong.Footnote 109 In particular, judges, the leaders of the legal practitioners, use their intellectual or cognitive capacities to convince all practicing lawyers to assist their clients in using mediation and other alternative processes to resolve shareholder disputes. Lawyers also play a key role in assisting their clients to explore the benefits of using ADR to resolve shareholder disputes. The legitimacy of ADR derives from a cognitive process through which ADR promoters employ a symbolic (such as the use of law) or rhetoric (the use of language) device that connects ADR practice to the existing legal culture.Footnote 110 The present empirical study provides evidence supporting that law can be viewed as a powerful policy instrument to convey a message to lawyers that ADR was perceived as being compatible with court-based shareholder proceedings.Footnote 111 Similarly, the empirical findings of this study also demonstrate that the legitimacy of ADR requires active efforts of ADR promoters to employ non-legal instruments (such as ADR training) encouraging Hong Kong lawyers to adopt ADR on behalf of their clients.Footnote 112

Last but most importantly, much remains to be done in refining Hong Kong’s current ADR programme by looking elsewhere for direction towards international expectations for the development of sophisticated ADR programme for shareholder disputes.Footnote 113 This book further proposes that two conditions theoretically help ensure that the new corporate law, the amended civil procedure rules and a set of ADR referral directives issued by the Judiciary could achieve their maximum impact on further policy development of ADR in Hong Kong.

First, the inclusion of ADR into the voluntary codes of corporate governance for small and medium-sized private companies in Hong Kong is to be welcomed as it provides additional guidelines for the court to determine the appropriate standard of conduct for directors to behave in a manner which is consistent with ADR goals.Footnote 114 Second, the new Companies Ordinance that permits a minimum level of judicial intervention with regard to jurisdictional limits of the arbitral tribunals to grant specific kinds of relief such as a winding-up order should be retained.Footnote 115 This approach permits greater freedom for private companies to contract out some of the members’ statutory rights to file a petition to the court through an arbitration agreement, while retaining a certain degree of the court to control over the specific kind of remedies that the arbitral tribunals should not be granted.Footnote 116

1.3 Organization of the Book

This book is organized into three key parts. Part I includes this introductory chapter and Chapters 2 and 3. Chapter 2 provides an overview of the recent development and growth of ADR in the resolution of shareholder disputes in Hong Kong. Chapter 3 then develops a methodological framework for evaluating policy development on ADR in resolving shareholder disputes. It provides a rationale for and description of data collection methods and instruments, as well as for data analysis techniques.

Part II comprises three chapters, with a focus on how mediation and other out-of-court processes can secure legitimacy from corporate law, court rules, judicial directives on mediation and the support of the local legal professions. Chapter 4 analyses the policy reasons for the development of court-connected ADR procedures in Hong Kong. This analysis helps to determine whether the amended court rules together with a set of judicial referral directives have improved the legitimacy of the court to further promote the greater use of ADR in resolving shareholder disputes. Chapter 5 considers how the reform of provisions concerning protection of minority shareholders facilitates the coexistence of both informal out-of-court processes and court-based shareholder proceedings. Chapter 6 seeks to identify the key factors affecting the attitudes of Hong Kong lawyers to choose ADR methods in helping their clients to resolve shareholder disputes.

Part III consists of one chapter, which explores the feasibility of formulating a set of specific company law provisions in relation to the proper use of out-of-court processes for the resolution of shareholder disputes in Hong Kong. Chapter 7 includes the use of comparative sociology of law to develop three testable series of arguments regarding the conditions under which Hong Kong may learn from the experience of the United Kingdom, New Zealand and South Africa by incorporating the use of informal dispute resolution methods into the company legislation.

Finally, a concluding chapter summarizes the findings presented in the earlier chapters. This chapter concludes the study by drawing together the main themes of the book in relation to the process of institutionalizing the greater use of extrajudicial processes for the resolution of shareholder disputes. This analysis provides more detailed recommendations for future research purpose. In particular, it underlines the importance of developing other sophisticated empirical models to examine the unfolding changes of an institutional process that could ultimately lead to the stage of full institutionalization.

Some important limitations to the present study should be acknowledged at the outset. First, this study does not attempt to resolve the broad issues in attempting to expand the scope of ADR applications in derivative actions. Instead, it focuses on shareholder disputes, primarily on disputes between minority and majority shareholders in a private company registered in the Hong Kong Company Registry. Second, this book is concerned primarily with shareholder disputes rather than corporate conflicts. It pays more attention to examining how and why the development of a variety of policy instruments can secure the legitimacy of innovative dispute resolution processes for handling shareholder disputes in Hong Kong. Third, the study does not employ substantive case law analyses together with the historical perspectives in analysing the substantive law development that have impacted on the development of unfair prejudice proceedings. Fourth, the empirical study is limited to analysis of Hong Kong lawyers’ attitudes towards the use of mediation instead of other modes of non-litigation dispute resolution processes (such as arbitration and expert determination). This is predicated on the fact that the intentions of the CJR together with the Chief Executive’s Policy Address of the Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region are to encourage the parties and their legal representatives to pursue mediation. Last but not least, this study is limited to the theoretical realm by comparing with those common law jurisdictions including South Africa, the United Kingdom and New Zealand which have developed sophisticated ADR programmes for resolving shareholder disputes.