Book contents

- Writing Sounds in Carolingian Europe

- Cambridge Studies in Palaeography and Codicology

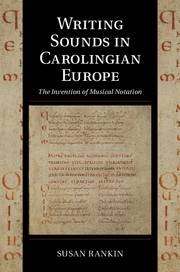

- Writing Sounds in Carolingian Europe

- Copyright page

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Examples

- Note on Musical Examples

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Part I Musical Literacy

- Part II Music Scripts

- Part III Writing Sound

- Appendix Manuscripts with notations written in the ninth century

- Bibliography

- Index of Manuscripts

- Index of Chants and Songs

- General Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 November 2018

- Writing Sounds in Carolingian Europe

- Cambridge Studies in Palaeography and Codicology

- Writing Sounds in Carolingian Europe

- Copyright page

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Examples

- Note on Musical Examples

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Part I Musical Literacy

- Part II Music Scripts

- Part III Writing Sound

- Appendix Manuscripts with notations written in the ninth century

- Bibliography

- Index of Manuscripts

- Index of Chants and Songs

- General Index

- References

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Writing Sounds in Carolingian EuropeThe Invention of Musical Notation, pp. 370 - 390Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2018