Book contents

- Orthodox Judaism and the Politics of Religion

- Orthodox Judaism and the Politics of Religion

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on Terminology

- Introduction

- 1 Of Priests and Prophets

- 2 The Genesis of Orthodox Political Camps

- 3 Interwar Poland

- 4 Divisive Land

- 5 A New Era in Orthodox Relations

- 6 Emerging Israeli Milieus

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

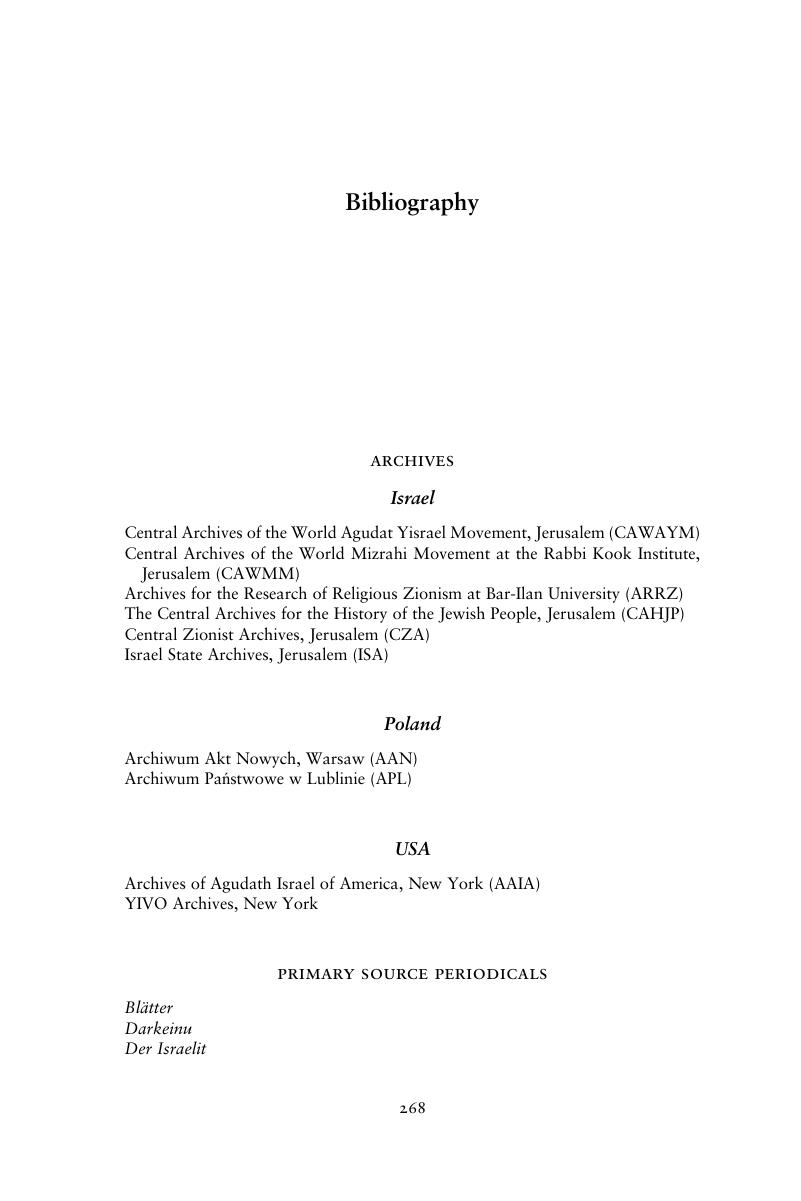

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 06 March 2020

- Orthodox Judaism and the Politics of Religion

- Orthodox Judaism and the Politics of Religion

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on Terminology

- Introduction

- 1 Of Priests and Prophets

- 2 The Genesis of Orthodox Political Camps

- 3 Interwar Poland

- 4 Divisive Land

- 5 A New Era in Orthodox Relations

- 6 Emerging Israeli Milieus

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Orthodox Judaism and the Politics of ReligionFrom Prewar Europe to the State of Israel, pp. 268 - 295Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020