Book contents

- Antifascist Humanism and the Politics of Cultural Renewal in Germany

- Antifascist Humanism and the Politics of Cultural Renewal in Germany

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: Antifascist Humanism and the Dual Legacies of Weimar

- Part I Defending the “Other Germany”

- Part II Contesting “Other Germanies”

- Conclusion: From the Saar to Salamis

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

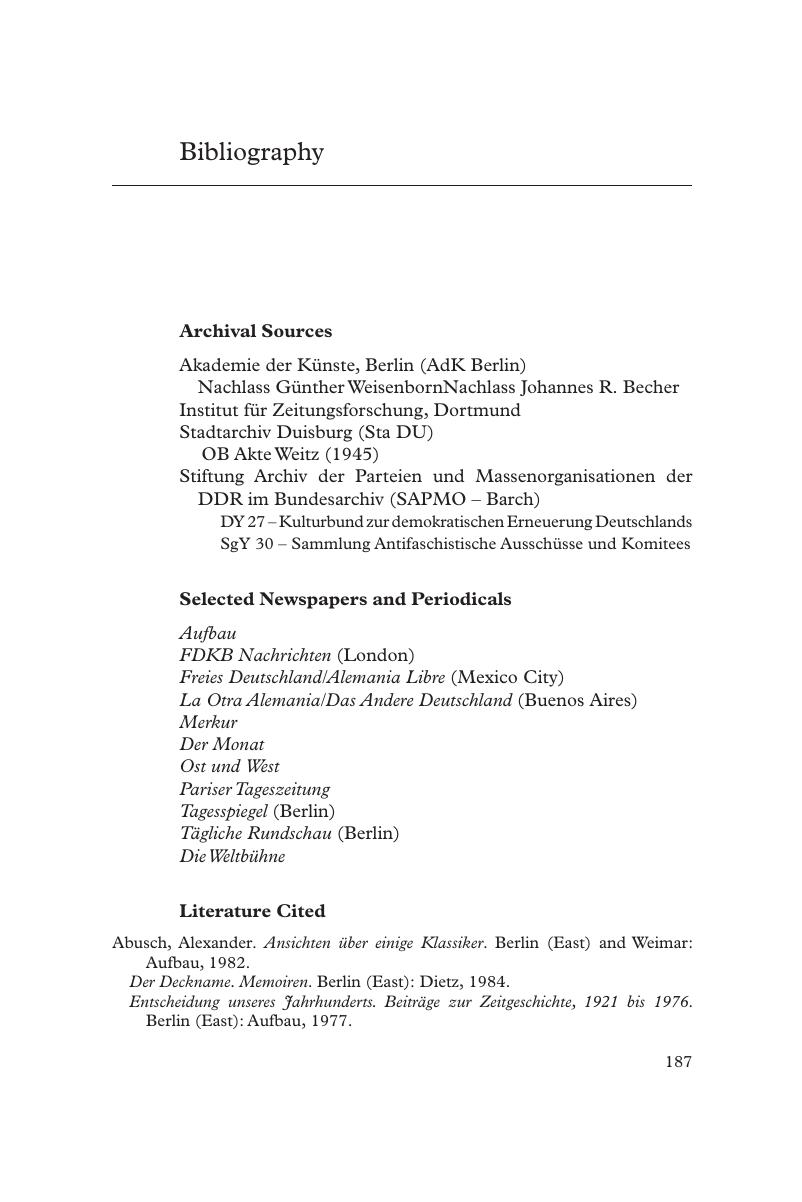

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 July 2017

- Antifascist Humanism and the Politics of Cultural Renewal in Germany

- Antifascist Humanism and the Politics of Cultural Renewal in Germany

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: Antifascist Humanism and the Dual Legacies of Weimar

- Part I Defending the “Other Germany”

- Part II Contesting “Other Germanies”

- Conclusion: From the Saar to Salamis

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017