Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 January 2023

Summary

All you who enter here, abandon hope!

The literature of hell is certainly voluminous. Narratives of a descent into the underworld, of the sights to be seen there, and the punishments meted out, have always had a strong hold on the creative imagination. Hell has appeared over millennia in the stories mankind tells. It functions as a religious belief, as a disciplinary threat to enforce social conformity, as a metaphor for man’s inhumanity to man, as a barbed satiric riposte, and as a source of entertainment, whether to produce thrills and spills or ludic transgressions.

In religious terms, hell can be identified as the supreme place of retribution for wrongdoing, where the judgement imposed on deceased individuals by a superior authority is unalterable. In both the Christian and Islamic traditions, the torments in hell will endure for all eternity. This is the place to send enemies: those who oppress the faithful or the vulnerable, those who cold-heartedly exploit people or natural resources for their own material gain, those identified as the accurst. Yet universal agreement is not to be found on what constitutes either an afterlife or a hell. The Hebrew Bible gives little detail of an afterworld, for instance, and Buddhist thought makes the punishments in hell purgative, part of Samsara (the cycle of death and rebirth).

There is no one vision of hell and no single thread of representation. The fundamental motifs for a journey made by a living being to the land of the dead and for a post-mortem judgement day (a river crossing, or the image of a precariously narrow bridge which spans the divide between the worlds of the living and the dead, the scales of justice where the merit of an individual’s life will be weighed, a lake of fire) come to us from the ancient religions and myths of Mesopotamia and Persia. These ideas are passed forward through a number of routes (for instance, through trade or imperial expansion or by means of pedagogical systems), but retain their valency due to the powerful nature of the imagined geography and its focalised markers.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

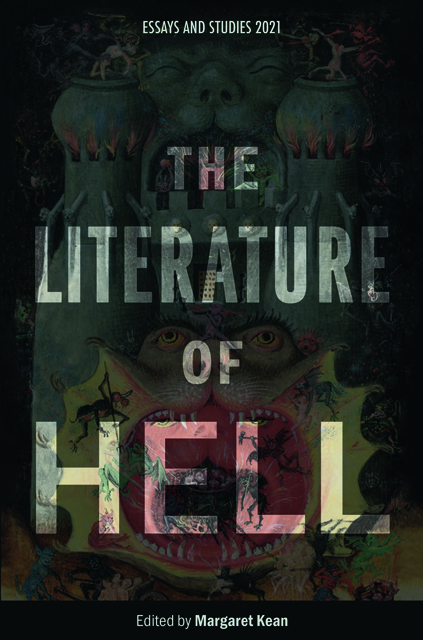

- The Literature of Hell , pp. 1 - 10Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2021