Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: “What's it going to be then, eh?”: Questioning Kubrick's Clockwork

- 1 A Clockwork Orange … Ticking

- 2 The Cultural Productions of A Clockwork Orange

- 3 An Erotics of Violence: Masculinity and (Homo)Sexuality in Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange

- 4 Stanley Kubrick and the Art Cinema

- 5 “A Bird of Like Rarest Spun Heavenmetal”: Music in A Clockwork Orange

- REVIEWS OF A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, 1972

- “The Décor of Tomorrow's Hell”

- “A Clockwork Orange: Stanley Strangelove”

- A Glossary of Nadsat

- Filmography

- Select Bibliography

- Index

“A Clockwork Orange: Stanley Strangelove”

Review in The New Yorker, January 1, 1972

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 January 2010

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: “What's it going to be then, eh?”: Questioning Kubrick's Clockwork

- 1 A Clockwork Orange … Ticking

- 2 The Cultural Productions of A Clockwork Orange

- 3 An Erotics of Violence: Masculinity and (Homo)Sexuality in Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange

- 4 Stanley Kubrick and the Art Cinema

- 5 “A Bird of Like Rarest Spun Heavenmetal”: Music in A Clockwork Orange

- REVIEWS OF A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, 1972

- “The Décor of Tomorrow's Hell”

- “A Clockwork Orange: Stanley Strangelove”

- A Glossary of Nadsat

- Filmography

- Select Bibliography

- Index

Summary

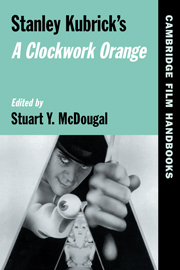

Literal-minded in its sex and brutality, Teutonic in its humor, Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange might be the work of a strict and exacting German professor who set out to make a porno-violent sci-fi comedy. Is there anything sadder – and ultimately more repellent – than a clean minded pornographer? The numerous rapes and beatings have no ferocity and no sensuality; they're frigidly, pedantically calculated, and because there is no motivating emotion, the viewer may experience them as an indignity and wish to leave. The movie follows the Anthony Burgess novel so closely that the book might have served as the script, yet that thick-skulled German professor may be Dr. Strangelove himself, because the meanings are turned around.

Burgess's 1962 novel is set in a vaguely Socialist future (roughly, the late seventies or early eighties) – in a dreary, routinized England that roving gangs of teen-age thugs terrorize at night. In perceiving the amoral destructive potential of youth gangs, Burgess's ironic fable differs from Orwell's 1984 in a way that already seems prophetically accurate. The novel is narrated by the leader of one of these gangs – Alex, a conscienceless schoolboy sadist – and, in a witty, extraordinarily sustained literary conceit, narrated in his own slang (Nadsat, the teen-agers' special dialect). The book is a fast read; Burgess, a composer turned novelist, has an ebullient, musical sense of language, and you pick up the meanings of the strange words as the prose rhythms speed you along.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange , pp. 134 - 140Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2003

- 1

- Cited by