Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword (David Langslow)

- PART I THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

- PART II EARLY LATIN

- PART III CLASSICAL LATIN

- 10 Hyperbaton and register in Cicero

- 11 Notes on the language of Marcus Caelius Rufus

- 12 Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretius

- 13 Campaigning for utilitas: style, grammar and philosophy in C. Iulius Caesar

- 14 The style of the Bellum Hispaniense and the evolution of Roman historiography

- 15 Grist to the mill: the literary uses of the quotidian in Horace, Satire 1.5

- 16 Sermones deorum: divine discourse in Virgil's Aeneid

- PART IV EARLY PRINCIPATE

- PART V LATE LATIN

- Abbreviations

- References

- Subject index

- Index verborum

- Index locorum

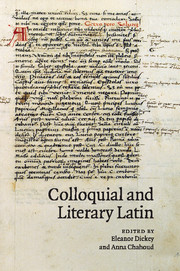

13 - Campaigning for utilitas: style, grammar and philosophy in C. Iulius Caesar

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2011

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword (David Langslow)

- PART I THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

- PART II EARLY LATIN

- PART III CLASSICAL LATIN

- 10 Hyperbaton and register in Cicero

- 11 Notes on the language of Marcus Caelius Rufus

- 12 Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretius

- 13 Campaigning for utilitas: style, grammar and philosophy in C. Iulius Caesar

- 14 The style of the Bellum Hispaniense and the evolution of Roman historiography

- 15 Grist to the mill: the literary uses of the quotidian in Horace, Satire 1.5

- 16 Sermones deorum: divine discourse in Virgil's Aeneid

- PART IV EARLY PRINCIPATE

- PART V LATE LATIN

- Abbreviations

- References

- Subject index

- Index verborum

- Index locorum

Summary

INTRODUCTION

C. Iulius Caesar is not a name that readily springs to mind in the context of an inquiry into the relationship between ‘colloquial’ and literary Latin; for ‘Caesar is incomparably the most “correct” of classical authors, if by “correct” we mean that he observes the “rules” of Latin orthography, grammar and word-order that would later become standardised by Palaemon and others’ (Hall 1998: 18). Caesar's linguistic self-discipline, which famously restricts the vocabulary of the Bellum Gallicum to less than 1,300 lexemes, is so thorough that it even affects and excludes forms, words and constructions which can hardly be called ‘colloquial’ if this term is taken as the opposite of ‘literary’. However, if we admit that colloquial Latin can also be taken to refer to ‘the Latin used conversationally by the upper … classes during the Republic’ (Dickey, this volume p. 66), in other words be equated roughly with what ancient theoreticians referred to by terms such as cottidianus sermo (Rhet. Her. 4.14; cf. Ferri and Probert, this volume pp. 14, 39), then Caesar might even be called the most colloquial of Latin authors: there is little in his writings which could not also have been said, without much stylistic effect, in a standard upper-class conversation of his time. All the more, though, the inclusion of a chapter on Caesar in this collection might seem pointless: for whether we call nothing or everything ‘colloquial’, the lack of substantial diastratic differentiation in the primary material provides little scope for illuminating comments.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Colloquial and Literary Latin , pp. 229 - 242Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2010

- 2

- Cited by