Conclusion

Summary

In a chapter which is tellingly entitled ‘Back to Dickens’, Mike Davis argues, in his book Planet of Slums, that the contemporary ‘dynamics of Third World urbanization both recapitulate and confound the precedents of nineteenth and early twentieth-century Europe and North America’ (2007: 11). Similar analogies between the Victorian slums of the nineteenth and the shan-tytowns of the twenty-first century have not only been drawn by sociologists, but also by filmmakers and writers. Danny Boyle has, for instance, compared Mumbai to ‘Charles Dickens’ Victorian London’ (Boyle 2009b) and the journalist George Packer has argued in his essay ‘Dickens in Lagos’ that

Dickens’ real heirs are less likely to have grown up in London than Bombay. It's no accident that one of the few great works of social realism of recent years was produced by an Indian-born writer, Rohinton Mistry, whose novel A Fine Balance begins with [an] epigraph from Balzac … In vast, impoverished cities like Bombay, Cairo, Jakarta, Rio, or Lagos, the plot lines of the nineteenth century proliferate. Not ignorant mass suffering, but the ordeal of sentient individuals who are daily exposed to a world of possibilities through a sheet of glass – satellite TV, the Internet – that keeps them out. The extreme conditions of megacity slums contain the extravagant material that animated Dickens. (Packer 2010)

Hence, apart from drawing analogies between Charles Dickens and Rohinton Mistry, Packer also points to the novel realities of globalised screen media that are shaping, for better or worse, the dreams, aspirations and hopes of many slum-dwellers today – a topic that has, however, already been explored in films like Moi, un noir or Salaam Bombay!, but still continues to be a prominent concern in more contemporary films like Cidade de Deus and Slumdog Millionaire.

With the latter example, this book concludes not merely with a return of ‘Dickens in Mumbai’. Evidently there is a much broader historical loop or cycle that has been outlined in this book: another turn-of-the-century conflation between emerging new media technologies and an immense multiplication of slum images and stories. To rephrase Douglas Muzzio and Thomas Halper's observation about the previous fin-de-siècle (see Chapter 2), in the digital era the slum – tied to a panoply of issues, from drug abuse, crime and gang violence to homelessness and social inequality – has returned as a topic of high visibility.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

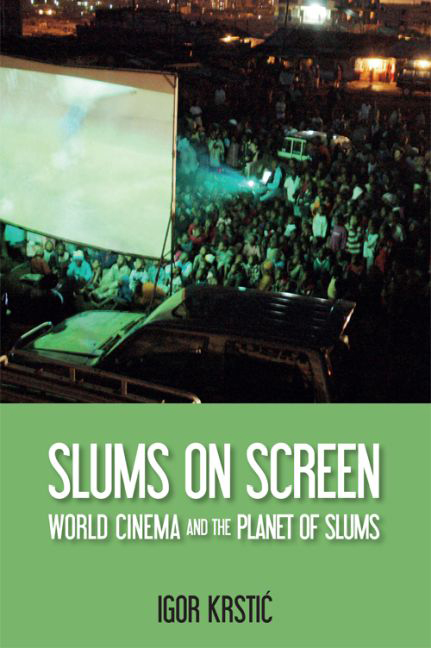

- Slums on ScreenWorld Cinema and the Planet of Slums, pp. 257 - 262Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2016