Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The Marble Camera

- PART I

- 1 The Sculptor's Dream: Living Statues in Early Cinema

- 2 The Mystery … The Blood … The Age of Gold: Sculpture in Surrealist and Surreal Cinema

- 3 Carving Cameras on Thorvaldsen and Rodin: Mid-Twentieth- Century Documentaries on Sculpture

- 4 Anatomy of an Ovidian Cinema: Mysteries of the Wax Museum

- 5 The Night of the Human Body: Statues and Fantasy in Postwar American Cinema

- 6 From Pompeii to Marienbad: Classical Sculptures in Postwar European Modernist Cinema

- 7 Of Swords, Sandals, and Statues: The Myth of the Living Statue

- 8 Coda: Returning the Favor (A Short History of Film Becoming Sculpture)

- PART II

- Bibliography

- About the Authors

- Index

5 - The Night of the Human Body: Statues and Fantasy in Postwar American Cinema

from PART I

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 June 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The Marble Camera

- PART I

- 1 The Sculptor's Dream: Living Statues in Early Cinema

- 2 The Mystery … The Blood … The Age of Gold: Sculpture in Surrealist and Surreal Cinema

- 3 Carving Cameras on Thorvaldsen and Rodin: Mid-Twentieth- Century Documentaries on Sculpture

- 4 Anatomy of an Ovidian Cinema: Mysteries of the Wax Museum

- 5 The Night of the Human Body: Statues and Fantasy in Postwar American Cinema

- 6 From Pompeii to Marienbad: Classical Sculptures in Postwar European Modernist Cinema

- 7 Of Swords, Sandals, and Statues: The Myth of the Living Statue

- 8 Coda: Returning the Favor (A Short History of Film Becoming Sculpture)

- PART II

- Bibliography

- About the Authors

- Index

Summary

Although it is conventional, and perhaps logical, to regard the avant-garde and the commercial cinemas separately, major new developments in each arose concurrently in the USA during the Second World War and, to some extent, in response to it. The dark Hollywood trend that was retrospec¬tively dubbed film noir could be seen, as Paul Arthur and David James have observed, as an industrial form of an equally dark trend in the new genre of art cinema that came to be known as the trance film: “both modes feature a somnambulist protagonist who enters a menacing, often incomprehensible environment in a search for sexual, social, or legal identity, and both states are characterized by the same deadened affect, increased capacity for absorb¬ing or inflicting violence, iconographies of entrapment, and the dissolution of geographic boundaries.”

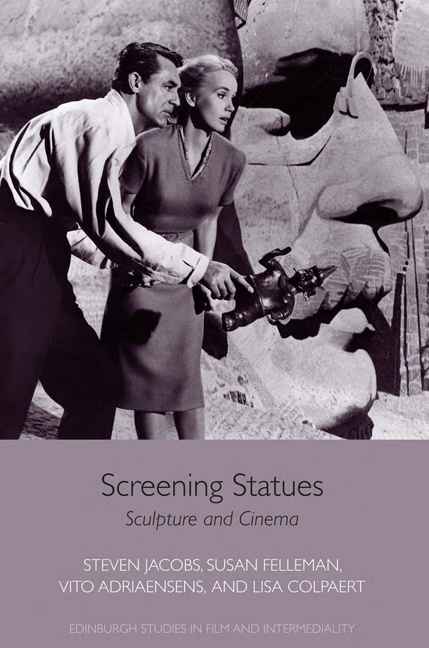

Influenced by the German Expressionist cinema, film noir was artier than the general Hollywood studio product. And the trance film, inaugu¬rated by Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid with Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) – in the tradition of works by such European filmmakers as Germaine Dulac, Jean Epstein, Dmitri Kirsanoff, the Surrealists and, especially, Jean Cocteau – was more narrative than the archetypal avant-garde film. Among the common attributes and imagery of noirs and their contemporary avant-garde cousins, sometimes referred to as psychodra¬mas, are dream sequences – often characterized by abstract imagery and special effects – and narratives featuring subjective formal devices such as first-person voiceover and complex flashbacks. And in a number of noir thrillers and melodramas such as The Maltese Falcon (1941), Three Strangers (1946), The Dark Corner (1946), and Stolen Face (1952), as often in the trance film, sculpture appears, as overestimated object of desire and as enigma.

Two films illuminate the poles of this historical nexus: Albert Lewin's MGM highbrow horror film, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945), which is a reflexive blend of noir atmosphere, stylized period mise-en-scène, and art en abyme, and Dreams That Money Can Buy, a noirish quasi-narrative feature, punctuated by experimental dream sequences, produced in 1947 with the help of art world friends and independently directed by émi-nence grise of the European avant-garde, Hans Richter.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Screening StatuesSculpture and Cinema, pp. 101 - 117Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2017