Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 “Till Ready,” to 1960

- 2 Inside the Record Industry, 1960–64

- 3 Freelance in London and New York, 1964–67

- 4 Chicago Years, 1967–73

- 5 Exchanging Criticizing for Supporting, 1973–76

- 6 The Pastoral Dream, 1976–79

- 7 Inside Music Publishing, 1979–84

- 8 Philadelphia, First Installment, 1984–91

- 9 Back to Holland, 1992–95

- 10 Philadelphia, Second Installment, 1996–2005

- 11 West Coast Years, 2005–14

- 12 Philadelphia, Yet Again, 2014–?

- Afterword

- Index

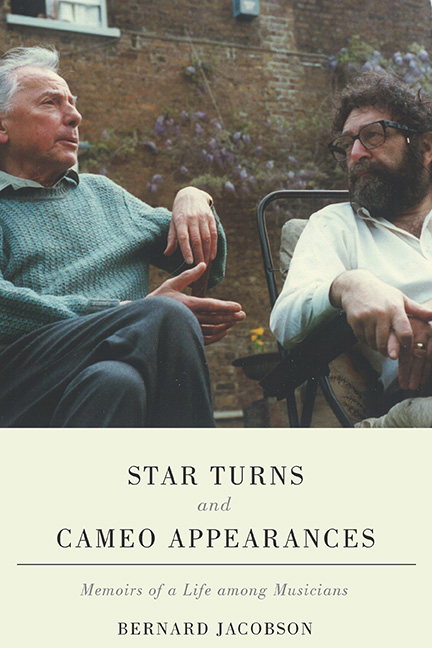

- Photographs follow page 148

- Plate section

9 - Back to Holland, 1992–95

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2016

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 “Till Ready,” to 1960

- 2 Inside the Record Industry, 1960–64

- 3 Freelance in London and New York, 1964–67

- 4 Chicago Years, 1967–73

- 5 Exchanging Criticizing for Supporting, 1973–76

- 6 The Pastoral Dream, 1976–79

- 7 Inside Music Publishing, 1979–84

- 8 Philadelphia, First Installment, 1984–91

- 9 Back to Holland, 1992–95

- 10 Philadelphia, Second Installment, 1996–2005

- 11 West Coast Years, 2005–14

- 12 Philadelphia, Yet Again, 2014–?

- Afterword

- Index

- Photographs follow page 148

- Plate section

Summary

Before accepting the Residentie Orkest post, I had asked Carli van Emde Boas, a friend since my time at Philips who lives in Amsterdam, whether moving back to Holland was a good idea. His response, penetratingly, was: “Let me put it this way—Holland is a terrible country, and Holland is the best country in the world.” I was to discover that both halves of his divided judgment were accurate. I already knew about the good side of Dutch society—notably the openness to foreigners and foreign cultures, which would be illustrated by a poster we saw on a house door on the street we were soon living on: “Nederland zit te vol mensen—racisten uit!” (Holland is too full of people—racists out!) But the society had changed radically since I had lived there in the early 1960s. Now a people of whom many were highly gifted seemed to have succumbed to a kind of national abdication of responsibility, and against that background what was in many ways a dream job soon took on nightmarish aspects.

What were the dreamier sides of my position? Well, one was the joy of occasionally discovering a notable talent in a performer previously unknown to me. I tried to listen to as many as possible of the unsolicited CDs that arrived on my desk every day. In one case, a disc of Mozart concertos by a gifted young German pianist named Gerrit Zitterbart, I was able to act immediately on the discovery. I had an opening for a soloist in a Mozart concerto and felt that, though I had not heard Zitterbart in the flesh, his live recording gave me sufficient evidence of his quality, so I dug out the letter that had accompanied the CD and called him with an invitation. He duly made an impressive debut appearance with the orchestra, and I have subsequently had the pleasure of encountering him again in recordings of Brahms piano trios and of three sonatas by Johann Christian Bach coupled with the concertos (K. 107) that Mozart arranged them into.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Star Turns and Cameo AppearancesMemoirs of a Life among Musicians, pp. 210 - 232Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2015