Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I The Age of Enlightened Rule?

- 1 Women's Political Authority in Maria Antonia Walpurgis von Sachsen's Talestris: Königin der Amazonen (Thalestris: Queen of the Amazons, 1763)

- 2 Maxims of Leadership for a Silent Readership: Sophie von La Roche's Pomona für Teutschlands Töchter and Mein Schreibetisch

- 3 Marcus Aurelius, Also for Girls: Discussions on the Best Form of Government in Enlightenment Hamburg

- 4 Dux Femina Facti: Gender, Sovereignty, and (Women's) Literature in Marie Antonia of Saxony's Thalestris and Charlotte von Stein's Dido

- 5 Crossing the Front Lines: Female Leadership, Politics, and War in Die Familie Seldorf

- 6 Power Struggles between Women in Schiller's and Jelinek's Works

- Part II Leadership as Social Activism around 1900

- Part III Women and Political Power in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

- Bibliography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

4 - Dux Femina Facti: Gender, Sovereignty, and (Women's) Literature in Marie Antonia of Saxony's Thalestris and Charlotte von Stein's Dido

from Part I - The Age of Enlightened Rule?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I The Age of Enlightened Rule?

- 1 Women's Political Authority in Maria Antonia Walpurgis von Sachsen's Talestris: Königin der Amazonen (Thalestris: Queen of the Amazons, 1763)

- 2 Maxims of Leadership for a Silent Readership: Sophie von La Roche's Pomona für Teutschlands Töchter and Mein Schreibetisch

- 3 Marcus Aurelius, Also for Girls: Discussions on the Best Form of Government in Enlightenment Hamburg

- 4 Dux Femina Facti: Gender, Sovereignty, and (Women's) Literature in Marie Antonia of Saxony's Thalestris and Charlotte von Stein's Dido

- 5 Crossing the Front Lines: Female Leadership, Politics, and War in Die Familie Seldorf

- 6 Power Struggles between Women in Schiller's and Jelinek's Works

- Part II Leadership as Social Activism around 1900

- Part III Women and Political Power in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

- Bibliography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

Vergil's Dido as Political Script

“DUX FEMINA FACTI” (A woman was leader of the deed): with these words Vergil's Aeneas concludes the narrative of misfortunes that forced a young merchant's widow named Dido to flee from her native Phoenicia to North Africa, where she founded—and became queen of— the city of Carthage. The genitive “facti’ refers to the stages of her flight. Dido, shocked to learn about the killing of her husband and urgently advised to leave the country, prepares her flight with allies (“fugam Dido sociosque parabat”); available ships are seized and loaded to carry the treasures of her pursuer Pygmalion to the open sea. What remains vague in the account is the exact role Dido plays at this stage. The three-word sentence at the end, “dux femina facti,” functions as a moment of investiture, underscoring that she took the lead. Yet the narrator's reticence—it is in fact the voice of the goddess Aphrodite, who recounts the history of Dido and Carthage to her son Aeneas—leaves some ambiguity as to why or how the merchant's wife became queen. On the one hand, the narrative suggests that, given the circumstances, it is only natural that Dido be the leader and hence no further explanation is needed. Yet on the other hand, “dux femina facti” can also be read as a notice to underscore a situation so unexpected that readers need to be informed explicitly in order to grasp what is happening: a woman became the leader. In light of the prevailing expectations in Western civilization the second interpretation appears more plausible. Though ancient history and literature abound with unjust and tyrannical (male) rulers, “dux femina” signals a state of exception, a disruption in the continuation of state power. In her seminal 1949 The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir concluded: “History shows that men have always had hold of all concrete power.” Though de Beauvoir does not focus on the history of women's relationship to political sovereignty in particular, her wry conclusion does apply to the field of political history, in which female sovereignty was never just “one rule after the other,” but always appeared as an exceptional case and an immanent risk.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

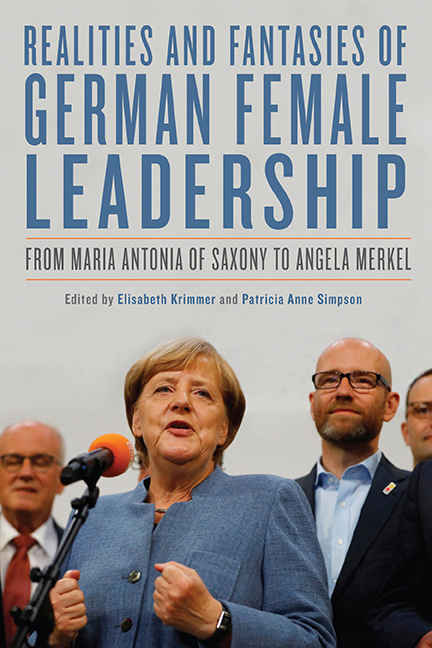

- Realities and Fantasies of German Female LeadershipFrom Maria Antonia of Saxony to Angela Merkel, pp. 97 - 112Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019