Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Back to the Future? Idioms of ‘displaced time’ in South African composition

- Chapter 2 Apartheid's Musical Signs: Reflections on black choralism, modernity and race-ethnicity in the segregation era

- Chapter 3 Discomposing Apartheid's Story: Who owns Handel?

- Chapter 4 Kwela's White Audiences: The politics of pleasure and identification in the early apartheid period

- Chapter 5 Popular Music and Negotiating Whiteness in Apartheid South Africa

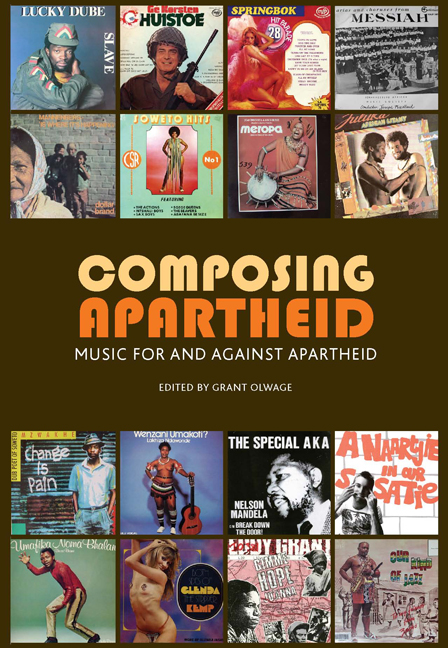

- Chapter 6 Packaging Desires: Album covers and the presentation of apartheid

- Chapter 7 Musical Echoes: Composing a past in/for South African jazz

- Chapter 8 Singing Against Apartheid: ANC cultural groups and the international anti-apartheid struggle

- Chapter 9 ‘Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika’: Stories of an African anthem

- Chapter 10 Whose ‘White Man Sleeps’ Aesthetics? and politics in the early work of Kevin Volans

- Chapter 11 State of Contention: Recomposing apartheid at Pretoria's State Theatre, 1990–1994. A personal recollection

- Chapter 12 Decomposing Apartheid: Things come together

- Chapter 13 Arnold van Wyk's Hands

- Contributors

- Index

Chapter 1 - Back to the Future? Idioms of ‘displaced time’ in South African composition

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Back to the Future? Idioms of ‘displaced time’ in South African composition

- Chapter 2 Apartheid's Musical Signs: Reflections on black choralism, modernity and race-ethnicity in the segregation era

- Chapter 3 Discomposing Apartheid's Story: Who owns Handel?

- Chapter 4 Kwela's White Audiences: The politics of pleasure and identification in the early apartheid period

- Chapter 5 Popular Music and Negotiating Whiteness in Apartheid South Africa

- Chapter 6 Packaging Desires: Album covers and the presentation of apartheid

- Chapter 7 Musical Echoes: Composing a past in/for South African jazz

- Chapter 8 Singing Against Apartheid: ANC cultural groups and the international anti-apartheid struggle

- Chapter 9 ‘Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika’: Stories of an African anthem

- Chapter 10 Whose ‘White Man Sleeps’ Aesthetics? and politics in the early work of Kevin Volans

- Chapter 11 State of Contention: Recomposing apartheid at Pretoria's State Theatre, 1990–1994. A personal recollection

- Chapter 12 Decomposing Apartheid: Things come together

- Chapter 13 Arnold van Wyk's Hands

- Contributors

- Index

Summary

Introduction

One evening in August 1997 I played a composition by a young black choral composer to one of my colleagues in the Fine Art Department at Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa. After listening to the strangely familiar yet unfamiliar language of the music, my colleague commented, ‘it∇s ostmodern’. It seemed to have arrived at a state of postmodernism without having been through European modernism, eschewing reference to art music of the early twentieth century (Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Bartók) and ignoring serial or post-serial techniques. What it lacked most conspicuously, however, made it what it was. It rearranged the codes and conventions from an earlier tonal era but projected them onto a flatter surface. Hence it sounded, to a colleague schooled in contemporary art but not music theory or composition, postmodern.

The codes this piece did employ belong to a substantial history and repertoire of written black South African choral music, but one transmitted half-orally because scores are scarce and choirs taught mainly by rote (see Lucia, 2005: xxvi). This is a tradition going back more than 125 years, with John Knox Bokwe (1855-1922) usually seen as colonial founding father (Olwage, 2006). The repertoire in this part of Africa has developed among hundreds of composers scattered throughout the region, adding idioms from various musical discourses encountered, including jazz, dance music, European classical, popular and folk music, African ‘traditional’ music, and church music of various kinds. Especially it feeds off its own histories; and along the way it has produced major composers and ‘classics’. The annual national competitions in which it is mainly performed, a culmination of local and regional competitions held throughout the year, make it seem as if there is a unitary history of such music; but the surviving repertoire comes from several historical periods and many areas of a large country, and is far from homogeneous in style and especially language, since the texts of choral songs are composed in all eleven official languages. Text and musical language articulate the experiences of black South Africans from colonial times to the present, and thus these pieces are valuable social documents.

On the production side: where scores have been preserved (and many have not) they are invariably hand-me-down copies of copies of manuscripts or typescripts.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Composing ApartheidMusic for and against apartheid, pp. 11 - 34Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2008