Article contents

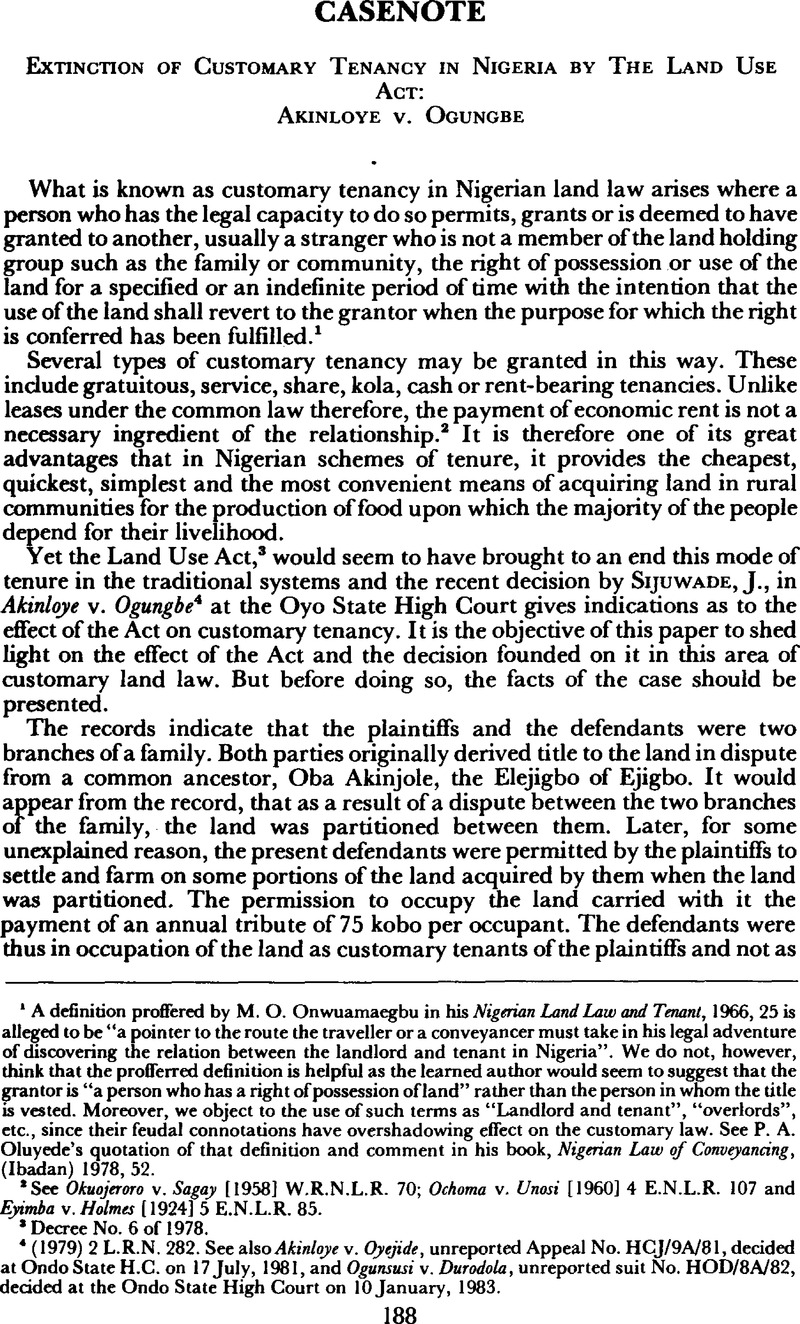

Extinction of Customary Tenancy in Nigeria by The Land Use Act: Akinloye V. Ogungbe

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 July 2009

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Case Note

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © School of Oriental and African Studies 1983

References

1 A definition proffered by Onwuamaegbu, M. O. in his Nigerian Land Law and Tenant, 1966, 25Google Scholar is alleged to be “a pointer to the route the traveller or a conveyancer must take in his legal adventure of discovering the relation between the landlord and tenant in Nigeria”. We do not, however, think that die profferred definition is helpful as the learned author would seem to suggest that die grantor is “a person who has a right of possession of land” rather than the person in whom the title is vested. Moreover, we object to the use of such terms as “Landlord and tenant”, “overlords”, etc., since their feudal connotations have overshadowing effect on the customary law. See Oluyede's, P. A. quotation of that definition and comment in his book, Nigerian Law of Conveyancing, (Ibadan) 1978, 52.Google Scholar

2 See Okuojeroro v. Sagay [1958] W.R.N.L.R. 70Google Scholar; Ochoma v. Unosi [1960] 4 E.N.L.R. 107Google Scholar and Eyimba v. Holmes [1924] 5 E.N.L.R. 85.Google Scholar

3 Decree No. 6 ofl 978.

4 (1979) 2 L.R.N. 282. See also Akinloye v. Oyejide, unreported Appeal No. HCJ/9A/81, decided at Ondo State H.C. on 17 07, 1981Google Scholar, and Ogunsusi v. Durodola, unreported suit No. HOD/8A/82, decided at the Ondo State High Court on 10 01, 1983.Google Scholar

5 See Ss.2 and 36 (3).

6 Sijuwade, J., found evidence justifying the intervention of equity to grant relief against forfeiture and could have reversed the customary court's decision without the application of the provisions of the Act. See his comments at p. 290.

7 Apart from this type of tenancy, there are other types of tenancies of definite periods or for particular purposes which terminate as soon as the periods expire or the purposes are achieved. These, however, do not usually present the sort of problems diat characterise tenancies of indefinite duration which are our main focus of attention in this paper.

8 Unreported Supreme Court Suit, decided in 1931, 29 08, 1931, referred to by Oluyede, , op. tit., p. 53.Google Scholar

9 Ibid.

10 See Etim v. Eke (1941) N.L.R. 430Google Scholar; Ochonma v. Unasi [1960] 4 E.N.L.R. 107.Google Scholar

11 See Onisiwo v. Fagbenro (1954) 21 N.L.R. 3Google Scholar; Ogbahmanwu v. Chiabolo (1950) 19 N.L.R. 107Google Scholar; Okuojeror v. Sagay (1958) W.R.L.R. 70Google Scholar; Vwani v. Akom (1938) 8 N.L.R. 19Google Scholar; Etim v. Eke (1944) 16 N.L.R. 43.Google Scholar

12 Lodo v. Akinliri (1975) 3 S.C. 9.Google Scholar

13 Elias, T. O., Nigerian Land Law, London, 1971, 90.Google Scholar

14 At 290.

15 See Smell's, Principles of Equity, 27th ed., 87 for the treatment of this topic.Google Scholar

16 Tito v. Waddell (No. 2) [1977] Ch. 106, at 225.Google Scholar

17 [1977] Ch. 106.

18 Ibid., 225.

19 See Olawoye, C. O., “Statutory Shaping of Land Law and Land Administration up to the Land Use Act” in Report of a National Workshop: The Land Use Act, Lagos, 1982, ed. Omotola, J. A., 18Google Scholar. See also 66 where Olaide Adigun expresses the view that the Governor is not a trustee in the conventional sense known to English jurisprudence. He thinks the concept of the State as the trustee accords with its objectives.

20 See Amodu Tijani v. Secretary, Southern Nigeria [1921] A.C. 399, at 404.Google Scholar

21 Omotola, J. A., op. cit., 37.Google Scholar

- 1

- Cited by