In 2004 the World Food Prize was awarded to the rice breeders Yuan Longping from China and Monty Jones from Sierra Leone.Footnote 1 Yuan was lauded for applying the heterosis effect to rice, creating hybrid rice varieties that were widely grown in China from the mid 1970s. Jones, working for the West Africa Rice Development Association (WARDA), received the prize for breeding rice varieties from crossing African rice (O. glaberrima) and Asian rice (O. sativa). The interspecific varieties were considered a breakthrough for rice cultivation in Africa and therefore named New Rices for Africa, shortened to NERICA (Figure 6.1). From the moment NERICA varieties were released, they were heavily promoted as the best option for African rice farmers to increase their yields and were hailed as a marked success of WARDA. In the early 2000s the distribution of NERICA lines had just begun. The uptake by farmers and the effects on rice production in the various rice-growing regions of Africa were largely unclear. By the end of the decade, when more reports on NERICA’s performance had appeared, it turned out that results were mixed at best.Footnote 2

Figure 6.1 A New Rices for Africa (NERICA) variety intended for use in lowland ecologies, one of several such varieties developed at AfricaRice in the 2010s.

The excitement over NERICA and the combined award for Yuan Longping and Monty Jones seem emblematic of the history of WARDA since its inception in 1970. Granting the World Food Prize to Yuan recognized his creation of hybrid rice and its contribution to the growth of rice production in China. The application of hybrid vigor or heterosis effect in rice requires a labor-intensive breeding and multiplication method. The technique results in F1 hybrid seeds that need replacement each year. The main advantage is that hybrids perform well with limited additional fertilizer. These features anticipated the limited production capacity for chemical fertilizer in China in the early 1970s, as well as the wide-ranging agricultural research and extension system embedded in rural communes.Footnote 3 The NERICA varieties were also a technical achievement in that they were based on crossbreeding two species, glaberrima, a rice species native to West Africa, and the sativa or Asian rice species. The main complicating factor for this breeding strategy is overcoming high sterility levels in the offspring, which was achieved by back-crossing interspecific lines with sativa lines. Linkages with the many rice farmers in West Africa, however, were poorly developed. The new varieties were tested at the WARDA farm, a set of experimental plots near the research station, rather than on actual farms in the region.

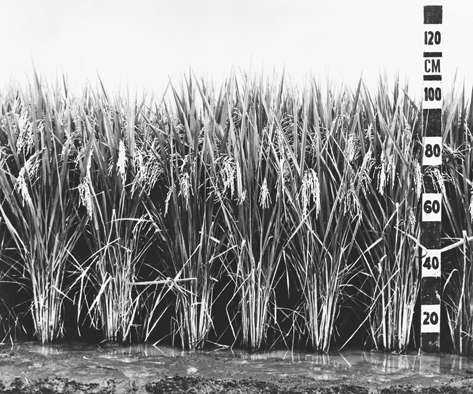

The work by Jones and his team thus was a technical achievement without the kind of effects on rice production in Africa that had been seen with hybrid rice in China. The criticism WARDA received for the triumphant claims over NERICA was acknowledged in later years and taken as an incentive for further testing of NERICA varieties in different African countries.Footnote 4 The fact that such further testing happened after the launch of the NERICA lines, and not before, suggests that the technical challenge of achieving an interspecific hybrid was prioritized over questions about what kinds of rice varieties were needed and how these were best distributed to African rice farmers. Moreover, the sativa varieties selected for backcrossing made the NERICA varieties fertilizer-responsive, like Asian improved varieties. As various studies have pointed out, agricultural improvements in Africa are typically framed as an African version of the Green Revolution in Asia, a framing in which technical similarities are considered capable of overcoming ecological, social, and economic differences.Footnote 5 Such framings turned the NERICA lines into evidence that WARDA was a rice-breeding institute comparable to the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), famed for its contribution of the “miracle rice” IR8 to the Green Revolution in Asia (Figure 6.2), and that similar effects on rice production would follow from WARDA’s breeding program.

Figure 6.2 IRRI’s semidwarf IR-8 rice variety, the standard against which later rice-breeding efforts would be measured. Rockefeller Archive Center, Rockefeller Foundation photographs, series 242D.

The question of whether and how WARDA’s trajectory compared with that of IRRI is indeed central in most historical accounts of the organization, which was renamed the Africa Rice Center in 2009 after widening its scope and membership to other African countries.Footnote 6 A key feature of IRRI is that it operated as a centralized research institute, concentrating scientific and technical expertise at a single research location. A major assumption of the centralized model was the isolation of research and plant-breeding techniques from diverse and locally specific environments. The aim was to develop “breakthrough” rice varieties that would have “wide adaptability,” suggesting the variety would be transferable across regions with largely similar conditions. The association of centers with research eminence created expectations that IRRI delivered on in 1966 with the launch of IR8.Footnote 7 Awards and prizes subsequently conferred stardom to plant breeders and confirmed the status of research institutes as “centers of excellence.”Footnote 8

Existing historical accounts of WARDA take this model as the leading principle for understanding how the institute emerged and, in the 1990s, was ultimately turned into a centralized rice research institute ready to produce transformative rice varieties in the African context. Delays in WARDA’s development are typically explained as resulting from an unclear research mandate at its inception in combination with limited budgets and shortages of trained staff. As WARDA’s main historian, John Walsh, put it: “in the fundamental matter of research strategy WARDA had gotten off on the wrong foot.”Footnote 9 However, a broader historical examination of research strategy, one that considers the breeding environment, including the ecology, economy, and social-political features of rice farming, puts WARDA’s history in a different light. As I demonstrate in this chapter, WARDA initially focused on rice-farming environments defined in the colonial period. The colonial focus on rice was closely linked to exports to Europe and related commercial interests. Moreover, the colonial policies excluded a major environment where West African farmers grew rice, namely the forested humid uplands zone.

WARDA shifted its focus to the humid uplands in the early 1990s, with decisive consequences. As argued by experts within and outside CGIAR (Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research), the humid uplands required a different research strategy, one in which variation in farm types was the starting point. The CGIAR Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) urged WARDA to engage with such an approach, known as farming systems research. Experts also argued that a research agenda for the humid uplands required a decentralized breeding strategy. Although these consequences of its changed research target were acknowledged in the official documents, WARDA chose a different route by further centralizing research and concentrating on the technical ambition of breeding interspecific hybrids. Here I present the history of rice research in West Africa between the 1930s and 1990s from a perspective that considers rice farming and rice breeding as coproduced by ecological and social environments. In the conclusion, I reflect on how this historical perspective sheds a different light on the controversial launch of NERICA varieties as a breakthrough in rice improvement.

Colonial Rice Environments in West Africa, 1930–60

From the early decades of the twentieth century colonial policies were framed as “civilizing missions” that aimed to improve the living standards of people in colonized territories by investing in the local economy.Footnote 10 Colonial investments in agriculture chiefly focused on crops that supplied European industries and consumers. For the French and British territories in West Africa, the main products were cotton, coffee, cocoa, palm oil, and timber. A key problem for the colonial enterprise, including the production of these agricultural exports, was labor. West Africa had been a major area of enslavement, and colonizing powers sought new mechanisms to secure human labor after the abolition of slavery. Colonial administrations and private companies used the disguise of taxation and dodgy contracts to force African people’s labor on plantations or enforce their delivery of specified quantities of agricultural produce. From about the 1930s colonial powers introduced settlement schemes to boost agricultural production in Africa.Footnote 11 Large areas of land in low-population areas were prepared as new production sites where relocated families were given plots to produce certain crops, usually a combination of food crops for local consumption and crops for export. The settlement schemes provided all the facilities needed to farm the land, and scheme managers promised prosperity to settler farmers if they produced the prescribed crops in sufficient quantities.

One of these schemes, the Office du Niger, was built along the Niger River in French Sudan (present-day Mali). The history of the irrigated land settlement program of the Office du Niger, vividly documented by Monika van Beusekom, shows a gradual shift in the main crop from cotton to rice.Footnote 12 French colonial officials had pointed out the potential of rice cultivation along the Niger River when planning the scheme, which had initially focused on providing cotton for the French textile industry. The major grain crops in the region were millet and sorghum, but farmers were growing rice on the riverbanks, using the seasonal flooding of the river. Colonial authorities anticipated further demand for rice in other colonized areas, for example Senegal, where the French had invested primarily in groundnuts.Footnote 13 The Senegalese groundnut schemes supplied the French oil-seed industry and increased the local demand for food. The growing rice imports from Asia to Senegal were another incentive to stimulate rice in the West African region, which the Office du Niger did by building irrigation infrastructure to facilitate a more permanent water supply to a larger area.

The Office du Niger irrigation and settlement scheme exemplifies the overall transformation of agriculture in West Africa set in motion by colonial agricultural policies. Colonial powers shared an optimism about science and technology, expecting lush harvests and quick returns on investments in roads, irrigation infrastructure, machinery, and mineral fertilizers. Researchers and technicians played a leading role in the African settlement schemes.Footnote 14 Although illustrating colonial policies in general, the schemes were also in many ways specific to the semi-arid Sahel region. In particular, the scale of the schemes and their dependency on irrigation infrastructure made them costly and necessitated a substantial layer of managerial and technical staff. After 1945 the French colonial authorities continued the investments in irrigated rice, although new schemes were substantially smaller in size.

The irrigated river schemes provided a major impetus for rice research. Two research stations were established to serve these schemes. The first was created in 1927 in Diafarabé (Jafarabe) in the Mopti region and attached to the Office du Niger in 1930.Footnote 15 Because the Office du Niger scheme opened up large stretches of land for which rice was a new crop, a principal task of the Diafarabé station was testing rice varieties that would perform well under irrigated conditions. Researchers also tried to find out more about these farming environments, for example studying the different soil types and soil fertility levels. The second research station was established in the 1940s at Richard Toll, attached to one of the smaller irrigated rice schemes along the Senegal River. These stations were later included in WARDA, together with two further stations located in Ivory Coast and Sierra Leone.

These additional two stations had different origins. The French colonial policy of stimulating export crops and food crop production in Ivory Coast focused on two regions. A forest region, covering roughly half the country northward from the coast, featured export crops that were perennials, mainly cocoa and coffee. Timber was also an export product. Producing these exports formed a major share of the economy, resulting in an increasing inflow of migrants. Although people grew food crops, including rice, in the forest zone, these types of farming were considered detrimental for the forest.Footnote 16 Growing food crops was instead stimulated in the drier savanna area further north, in combination with cotton production. The rural migration triggered by economic policies mixed ethnic groups as well as cropping patterns across the region. Whereas rice cultivation in Ivory Coast had been limited to the southwest forest region, halfway through the twentieth century rice was grown by smallholder farms across the colony, resulting in a wide variety of rice-farming methods and preferences for particular rice varieties.Footnote 17 From 1955, the French colonial administration also introduced small irrigation schemes in the savanna zone, together with further intensification of cotton cultivation.Footnote 18 To support these schemes, a rice research station in Ivory Coast was located in the southern savanna area at Bouaké, which was a major center for the cotton industry thanks to its location on the railway line running north from Abidjan. Rice research at the Bouaké station focused on selection of varieties for the dry upland rice farms.

One other rice research station eventually included in WARDA was created by the British colonial administration in Sierra Leone. Policies in the British West African territories were broadly similar to those in the countries controlled by France. The colonial economy of Sierra Leone had a somewhat different history, in that after the 1930s mining became increasingly important and by the 1960s, when it was an independent nation, completely dominated the country’s exports.Footnote 19 Investments in food crop production therefore were less directly connected to areas developed for export crops than in the settlement and irrigation schemes elsewhere. However, rice was considered a potential export crop, and indeed Sierra Leone exported rice in the 1930s and 1950s when farmers responded to favorable global price fluctuations.Footnote 20 As colonial experts quickly found out, rice yields in lowland areas along the rivers and inland swamps were higher than in the humid uplands. Concerns over the negative effects of slash-and-burn farming in the forest zone further motivated a focus on lowland areas. Colonial experts considered the rice farms in the Great Scarcies River area, located in the southwest bordering Guinea, to have the most potential. There, the nearness of the ocean caused tidal flows and extended mangrove forests, coastal conditions that farmers used to their advantage, resulting in one of the most productive rice areas of the country. Colonial officials thought that yields could be further increased with water control and other introduced techniques, making the Scarcies region a model for the rest of the country.Footnote 21 A rice research station was operational from 1934 in Rokupr, one of the nodes in the trade network for rice from the Scarcies region.

In sum, the rice research stations in the French and British colonial contexts of West Africa focused on farming environments that contributed, or were complementary, to an export-oriented economy. In the upper Sahel region, the river-based flooded farms were turned into much larger irrigation schemes where rice became the dominant food crop. The stations at Diafarabé and Richard Toll addressed the demands of farming rice in these conditions. Meanwhile, in Ivory Coast and Sierra Leone, two countries with substantial forest zones in which rice was an important crop, colonial officers largely ignored rice cultivation in the forested humid uplands. Intensification of rice cultivation in Ivory Coast concentrated on the northern dry savanna area, where rice complemented cotton growing. In Sierra Leone the emphasis was on tidal flooding in the coastal area and other lowlands that allowed for inundated rice cultivation.

Despite the restricted focus of rice research on dry uplands and inundated lowlands, research activities had effects beyond these target environments. The search for rice varieties that performed best in the Sahelian schemes, coastal areas, or dry savanna regions triggered a lively exchange of rice varieties on a global scale. Colonial experts were well networked and often travelled between different colonial territories, bringing rice varieties themselves or making requests to have varieties sent over. Varietal improvement during the first half of the twentieth century consisted primarily of sorting, recording, and testing the many different rice types. Named varieties were often so-called landraces, groups of morphologically similar types, which breeders further split up into “pure” lines. The starting point for breeders’ selection work was the varieties that farmers held in their fields. An example is the variety Demerara Creole, originating from British Guiana in South America. In the early twentieth century, sugar cultivation in British Guiana relied on indentured laborers from India, many of whom continued as smallholder rice farmers in the coastal zone. Colonial agronomists identified Demerara Creole as a landrace introduced to British Guiana by these Indian plantation workers.Footnote 22 The first descriptions of the variety in British Guiana date from the 1900s, and soon thereafter it was introduced to Sierra Leone.Footnote 23 From there it spread along the coast and further inland, also passing the border with French Guinea, where it was observed by the French botanist Roland Portères.Footnote 24 Many other varieties from within and outside the West African region were collected for further selection, followed by intentional and unintentional distribution.Footnote 25 Whereas colonial rice breeders primarily looked for varieties for targeted rice zones, the varieties also circulated more widely via informal distribution channels, reaching all rice areas, including the forested rice zones.

Colonial experts were aware of the wider effects of their work. The emergence of research stations and the often long-term involvement of experts in colonial programs implied that local agricultural practices were observed, if not closely studied.Footnote 26 Various colonial experts in West Africa persistently reported on the importance of local farming practices and the value of farmers’ knowledge and skills. For example, farmers in the Office du Niger cultivated a variety of crops, including rice, on their own fields, within and outside the scheme, mostly producing better-quality and higher yields. The scheme’s main agronomist, Pierre Viguier, concluded in the late 1940s that the colonial policy had failed. What West Africa needed, he argued, was not more foreign technology but “the application of African formulas, inspired no doubt by more evolved techniques, but thought out by Africans, adapted to the needs, the means, the aspirations of African peoples.”Footnote 27 Colonial administrations, however, seemed fully convinced about the superiority of foreign farming technology. In the 1950s the introduction of tractor plowing and mechanization of other tasks in 4,500 hectares of the Office du Niger scheme was to overcome “indiscipline, labour bottlenecks, or incompetence on the part of the farmers.”Footnote 28 By the late 1950s the results showed an overall higher yield in the nonmechanized parts of the scheme. Similar observations were made in colonial Sierra Leone. Experts like the soil scientist H. W. Dougall had noticed that farmers used higher fields at the margins of the mangrove swamps “to establish their rice nurseries, cassava and sweet potato beds and occasional banana groves. It is doubtful if the system could be profitably improved upon.”Footnote 29 The colonial administration in Sierra Leone nevertheless continued with the introduction of mechanization and improved irrigation infrastructure in the lowland areas. These technologies appeared very costly, and once authorities gave up support for maintenance and other operational costs, farmers quickly reverted to their “African formulas.”

Dependent and Independent West African Rice Environments in the 1960s

Between the end of colonial domination around 1960 and the establishment of WARDA in 1971, two major developments affected the course of rice research in West Africa. The independent West African nations started to transform colonial policies into national plans to stimulate the economy and agriculture. Few countries managed to do so without foreign support, and therefore former colonial powers and new international donors entered the scene. A second development was the strategy of the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations, backed by the US government, to boost food production in Asia and produce what has since been known as the Green Revolution. The strategy focused on plant breeding, resulting in varieties of wheat and rice that allowed for double cropping and overall high yields in areas with proper irrigation facilities and availability of mineral fertilizer. The philanthropies and US aid agencies pushed other international actors and Western allies to help apply the same strategy in other areas, including Africa.

Although the economic challenges for the independent West African states were broadly similar, there were major differences among country-level policies. For example, Ghana, independent in 1957, profited from the high price of cocoa in the 1950s, providing the government with revenues for investment in the economy. Rice was a relatively recent food crop in Ghana, and by the mid 1960s the government aimed for an expansion of rice production, with the help of Chinese experts and funds.Footnote 30 In Sierra Leone, where rice was the predominant food crop, the government had few financial reserves and fully relied on foreign support for rice improvement, which was provided by Taiwan. In 1968, when elections in Sierra Leone created a regime change, the new government opted for support from China.Footnote 31 The presence of China and Taiwan in West Africa makes clear that assistance programs for food production in Africa, as in Asia, were affected by the Cold War.Footnote 32

The new geopolitical constellation of the Cold War was also entangled with ongoing colonial dependencies. France and Britain held a firm overall grip on the economic interests in their former West African territories, mainly by securing commercial exploitation of lucrative export crops. France also coordinated agricultural research activities for tropical agronomy and food crops through a new umbrella organization created in 1960, the Institut de Recherches Agronomiques Tropicales et des Cultures Vivrières (IRAT).Footnote 33 Although new independent governments were formally in charge of agricultural research, IRAT’s headquarters were in France, and the budgets, staffing, and research agendas of the stations in West Africa were controlled from Paris.Footnote 34 Circumstances differed in former British colonies. Although independent governments had taken over all responsibilities for agricultural research, many British colonial experts continued to advise and support these countries, switching jobs from colonial service to national and international aid agencies.Footnote 35 The British centralized research structure established in 1953, in which the Rokupr research station had coordinated rice research across all British West African countries, was dismantled. Rokupr became the national research center for Sierra Leone in 1962, integrated with the agricultural research station and college at Njala.Footnote 36 In countries like Nigeria, Liberia, and Ghana, rice research was similarly taken up in national agricultural research agendas. As I describe below, the continuation of a centralized research organization by France would play a major role in the establishment of WARDA.

Towards the end of the colonial period, French and British researchers had started crossbreeding experiments to further fit rice varieties to West African environments. The breeding programs had resulted in various new releases for the target regions but were also distributed to other areas through local trading networks. Continued plant-breeding experiments at the research stations after independence included crossings between sativa and glaberrima rice varieties. Halfway through the 1960s such interspecific crosses were made in Sierra Leone and Nigeria. IRAT researchers did the same somewhat later.Footnote 37 None of these experiments resulted in stable lines that were released for distribution. Among other challenges, the decolonization of research in former British colonies quickly reduced the research capacity. By the end of the 1960s there were four full-time rice breeders, one each in Sierra Leone and Liberia and two in Nigeria.Footnote 38 Local resources compensated for new limitations. At Rokupr, for example, the experimental fields were tended by women who grew their own crops at the edges of the rice fields and helped in sorting seeds of the different varieties.Footnote 39 The linkages with Njala University, in the eastern part of the country, created the option for training new rice experts. However, most government and donor money was spent on improvement projects. In sum, by the time US donors planned to expand international agricultural research to West Africa in the late 1960s, there was a rather strong French-run research infrastructure in former French territories, and a relatively weak research infrastructure in former British colonies.

The proposal for a new international rice research institute in West Africa emerged alongside the preparations for the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), which had been initiated by the Rockefeller Foundation officials George Harrar and Will Myers in 1962. Harrar and Myers proposed that the Nigerian government set up IITA on the campus of the University of Ibadan. The new research center would focus on various tropical crops – except rice, as it was initially assumed that IRRI would provide the research input for rice breeding.Footnote 40 However, the importance of rice as a food crop in West Africa and the distinctive rice ecologies of Africa invited calls for further institutional development. Two years after the opening of IITA in 1967, the American donors, joined by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), made arrangements for a central rice research center in West Africa, a move resisted by France as it continued to coordinate several rice research stations in the region.Footnote 41 The negotiations among these actors for the future of rice research in West Africa were chaired by UNDP officer Paul Marc Henry, who had previously worked in the region for the French government.

There were three organizational models on the table. In the first, the new rice center would primarily disseminate research results from IITA, IRRI, and the French rice stations across the region. A second model was to make it a coordinating institute for the existing rice research stations. A third option was to create a central research institute with the four existing stations as satellites. This last model was preferred by the representative of the Rockefeller Foundation, Will Myers, and IRRI’s director, Robert Chandler. The UNDP delegation proposed a variant that reinstated the coordinating role for the Rokupr station in Sierra Leone.Footnote 42 Final agreement was reached at a 1970 meeting in Rome hosted by FAO. The outcome followed the second model of establishing a coordinating institute for the existing research stations. The model suggested a centralized research institute, yet without its having a firm lead in research activities. In contrast to the somewhat obfuscated research mandate of the overarching institute, the task of the four research stations was spelled out in clear terms.

Research activities at the newly designated WARDA stations focused on irrigated and deep-flooded (or floating) rice in Senegal and Mali, mangrove rice in Rokupr, and upland rice in Bouaké. This division implied a rather straightforward continuation of the colonial-era research agendas, and in many ways it was a continuation. However, colonial dependencies had become entangled with the newly emerging aid relationships, Cold War politics, and diverging national policies across the independent states. Countries like Ghana and Nigeria, for example, started to invest in rice production under irrigated conditions that were very different from the irrigated rice zones in the Sahel region. The Rokupr station in Sierra Leone never exclusively focused on mangrove rice. It had had a much broader mandate in the 1950s and then turned into a national research station in the 1960s, at which point it focused on all rice environments in the country. The agendas of the four research stations were further challenged after WARDA became operational.

Redefining Rice Farming Environments, 1970–2000

From 1970 a growing number of international donors became involved in rice improvement projects in West Africa. This was further intensified by the integration of WARDA into CGIAR in subsequent years. One of the challenges for WARDA was to broaden the scope of the four research institutes it coordinated. As explained in the previous section, the stations had built up expertise for specific rice-farming environments within institutional contexts defined by the British and French colonial empires. In the new setting of WARDA, the colonial distinctions were formally gone, and country borders were to be exceeded. For example, Rokupr had little experience with research on mangrove rice other than in Sierra Leone. However, mangrove rice environments stretched out along the coast of West Africa, crossing various national and linguistic borders. Likewise, irrigated rice schemes existed in West African countries other than Senegal and Mali. Throughout the first three decades of WARDA’s existence, the focus of the four stations on distinct rice-farming environments gradually changed. As I show here, there were two major reasons for the shifts in focus: first, changes within the farming environments themselves and, second, increasing criticism about the exclusion of the upland humid forest zone from research agendas.

Connections between WARDA and IRRI implied that the improved rice varieties introduced in Asia would become available for African farmers. Direct transfers, however, were hardly an option. By the early 1970s most varieties released by IRRI focused on Asian rice environments, where irrigation and fertilizer were available and two or even three rice crops per year were possible.Footnote 43 The irrigation schemes in Senegal and Mali would in principle match these conditions. However, the Sahelian climate includes a relatively cold winter period, requiring further selection of cold-resistant varieties in order to achieve double cropping.Footnote 44 The farming environments of the Sahelian irrigation schemes not only differed from Asian irrigated rice schemes but also from other irrigated rice areas in West Africa. Compounding these concerns, the operational conditions of irrigated rice schemes in the Sahel changed substantially during the last decades of the twentieth century.

In Mali, the legacy of the Office du Niger had created disparities among farmers in terms of entitlement to land and irrigation water. Subsequent governments tried to solve inequities through state-imposed farmer cooperatives and village advisory councils. These social structures were often caught in a crossfire from ongoing government involvement and complaints from farmers.Footnote 45 The introduction of farmer-operated motor pumps aimed to reduce the dependency on national managerial bodies. Pump-based village schemes, applied in Mali and Senegal from the end of the 1970s, were largely successful in decentralizing rice production but did bring up new problems. Researchers noted, for example, that support mainly went to male farmers, marginalizing women who often had a major share in agricultural work. In one of the Senegalese schemes a Dutch-funded program developed new pump-irrigated farmland in collaboration with women’s groups. The women opted for vegetable crops rather than rice, as these better served their household food security concerns and relied on their knowledge about local food markets.Footnote 46 The women’s decision to prioritize their own food security concerns rather than government demands for rice was an example followed by many rice farmers when, in the 1990s, the winds of neoliberal policy reforms stopped the supply of cheap fuel, maintenance for the motor pumps, credit for fertilizers, and subsidies on rice. Farmers’ interest in growing rice dropped significantly, as did acreage of rice cultivation, and many village schemes were abandoned.Footnote 47 These changes dampened the high expectations about the potential of irrigated rice schemes in West Africa. Although irrigated rice continued as one of WARDA’s targets, its prominence was overtaken by attention to a different environment: rice farming in the forested humid uplands.

Soon after the establishment of WARDA, agricultural experts working in the region pointed out that rice farming in the humid upland zone deserved more attention. Despite the overall consensus that yield increases had to come from irrigated rice, the size of the humid uplands, in terms of acreage and number of farm households, could no longer be ignored. In its first quinquennial review of WARDA in 1979, CGIAR’s TAC noted that some WARDA officers considered the focus on dry upland rice by the station in Bouaké inadequate for the humid uplands.Footnote 48 The committee’s advice was to investigate and discuss the issue. In the next quinquennial review, conducted in 1984, the committee repeated the advice in stronger terms, noting that humid uplands are “a badly neglected area of rice research and development which deserves increased attention from WARDA, national rice research programs, and IRRI and IITA.”Footnote 49 The importance was repeated in subsequent years. By the early 1990s the continuum of rice ecologies in the humid uplands was the main focus for WARDA’s research. Of the four farming environments that had been set as WARDA’s research targets in 1970, only irrigated rice remained as a priority.Footnote 50 The focus on humid uplands was a major shift in WARDA’s strategy that had further consequences for its research agenda (Figures 6.3 and 6.4).

Figure 6.3 Rice demonstration plots featuring “Upland Germplasm” and “Lowland Germplasm” (the latter including NERICA lines) that were associated with a WARDA collaboration in Liberia funded by Japan, 2009.

Figure 6.4 Two rice researchers at an Africa Rice Center upland rice-breeding site on the Danyi Plateau, Togo, in 2007.

A key feature of the humid upland zone is that it contains a variety of soils with different water levels. The topographical sequence implies a continuum from higher parts with low water levels, to a middle zone with saturated soil conditions, to a lower swamp area with standing water for most of the rainy season. The variation in ecological conditions and water levels makes it difficult to breed or select a single rice variety suitable on all types of farmland. The anthropologist Paul Richards, who had studied rice farms in the humid zone of Sierra Leone since 1977, concluded that selecting and experimenting with a broad set of different rice varieties was common practice among farmers.Footnote 51 Richards reported in detail about farmers’ preferences and their selection of rice varieties that addressed different soil and water conditions, resistance to weeds or pest damage, growth duration in anticipation of labor peaks during harvest time, and integration with other crops. Richards’ studies found some resonance in reports produced within CGIAR. For example, the focus on ecological variation and integration with crops other than rice was a research area with overlapping interests at WARDA and IITA. In the 1980s IITA had initiated an “agro-ecological characterization of rice-growing environments” in West Africa.Footnote 52 In a report of this effort published in the early 1990s, the researchers argued for a further integration of the work of WARDA and IITA in analyzing farming systems and called for improved varieties based on regional variation.

The message was taken on board by the next external program review committee, which wrote in its 1993 assessment that “WARDA needs a farming systems approach to research with a strong ecological focus so as to be of short- and long-term environmental, social and economic benefit.”Footnote 53 What the studies and reports hardly mentioned was that a farming systems approach had implications for WARDA’s approach to rice breeding. A “strong ecological focus” in West Africa would require a variety of projects embedded in nation- and region-specific research and extension facilities. Rice breeding then would follow from region-specific characteristics and farmers’ needs. As Richards explained, farmers’ selection strategies were likely to be seen as irrational in the eyes of breeders and extension agents, who would “replace a profusion of uncertain and unstable variants of local land races with a much smaller range of fixed and reliable seed types.”Footnote 54 The breeder’s perspective would be valuable, Richards and colleagues argued, but only if based on a continuous dialogue between farmers and breeders to find the common ground in what “wide varietal adaptability” means from both perspectives.Footnote 55 One such breeding approach, participatory varietal selection (PVS), gained some leverage in national rice-breeding projects in West Africa. An evaluation study of PVS projects over the late 1990s showed that national researchers were positive about the approach and most concerned by the limited capacity of their national research organizations to expand the work. The study also pointed out that financial support from WARDA was very modest.Footnote 56 In the 1990s, the actual rice-breeding agenda of WARDA had fully focused on the interspecific crossing experiments.

Conclusion

The evidence presented in this chapter provides a very different history of WARDA from what can be found in the limited historiography of the institute. Existing accounts perceive rice research primarily as on-station research and breeding capacity. Such capacity was, by the time WARDA was created, scattered over different regional and national stations. WARDA’s initial mandate gave the institute a coordinating rather than a leading role in rice research and breeding. In the received view, the alleged lack of control of WARDA’s headquarters staff over the research agenda was resolved with the centralization of research at the Bouaké station in the 1990s, with a clear research focus on interspecific crossing. In contrast, WARDA’s history as presented here explored rice research from an environmental perspective, examining linkages between farming environments and rice research. This shows a trend in which WARDA continued to focus on the rice-farming areas defined in the colonial period, addressing European commercial interests rather than the concerns of West African rice farmers. The 1990s, was the decade in which the inclusion of the humid uplands implied that WARDA finally covered the variety of rice-growing environments in West Africa, acknowledging the importance of studying the diversity of farming systems and addressing them with such methods as PVS. This version of WARDA’s history provides a puzzling contradiction with existing historical accounts.

One possible explanation for the contradicting trends in WARDA’s history is the limited overall research budget that, together with increasing regional political instability in the 1990s, enforced a decision to concentrate resources on a restricted rice-breeding program. CGIAR faced shrinking budgets in the 1990s, and a civil war in Liberia prompted WARDA to move its headquarters to Ivory Coast. However, the challenging circumstances of the 1990s do not explain why centralization of research was not implemented in earlier decades, when pretty much all the options were there and known to CGIAR officials. Moreover, improved rice varieties were produced by various national and regional breeding stations. From the 1960s to the 1990s, this added up to almost 200 releases of improved varieties.Footnote 57 As noted above, the early breeding activities also included interspecific crossing experiments with glaberrima and sativa rice. In other words, centralization of research and breeding was not a necessary condition for developing the scientific or technical knowledge to produce interspecific crossing lines or improved varieties more generally. And as shown in the account of the negotiations leading to WARDA’s establishment in the late 1960s, the US donors preferred a central breeding institute but did not block other options. Moreover, by the 1990s, as centralization took hold, there was much more evidence that diverse and decentralized research would be a better fit for West African conditions.

An alternative explanation considers the contradictions in the history of WARDA as the effect of a delayed decolonization of rice research in West Africa. The research stations set up in countries formerly under French rule formed the backbone of WARDA’s research. During the colonial period, Britain and France largely applied the same policies. France, however, continued its control over research facilities in its former colonial territories until the 1990s, mainly to secure uninterrupted access to export crops.Footnote 58 The historiography from the colonial period further makes clear that experts were aware that, in the selected environments, rice cultivation methods aiming for high yields required high investments. Moreover, they acknowledged that the farming practices of West African rice farmers were highly effective, given prevailing conditions, covering a wider variety of farming environments. Nevertheless, the research organization established for WARDA in 1970 largely continued the research agenda set in the colonial period.

This may justify a conclusion that colonial interests controlled rice research at WARDA, in particular through the continued influence of French officials. However, official documents of WARDA only provide indirect evidence for this. And even in the unlikely scenario that French influences largely determined the course of WARDA’s research, CGIAR donors had various options to invest in a complementary rice research agenda. Rokupr, for example, had earlier dealt with a regional mandate, and in the 1960s countries such as Ghana and Nigeria had also initiated rice research. Another route to diversify rice research was through IITA, which indeed did conduct complementary rice research, including rice breeding. Moreover, CGIAR donors other than France were also active in countries like Senegal, suggesting that the focus on irrigated rice environments was considered an attractive option for multiple actors at least until the 1990s. This would compromise a conclusion that attributes WARDA’s research agenda and the limited and late attention to humid uplands to French intentions alone.

CGIAR donors likely considered irrigated rice the best option until the moment protectionist policies were dismantled. There is a striking synchrony between the economic reforms that ended the economic viability of large, irrigated rice environments and the promotion of a new model focusing on the humid uplands. This explanation still does not account for the decision to ignore the expert advice to focus on farming systems research and diversification of the breeding strategy – leaving as a final explanation the allure of a centralized research model, mentioned in the introduction.

The summary version of WARDA’s history would then be that there was sympathy, but never strong conviction, for a diversification of WARDA’s research agenda. The need to strengthen decentralized, national research capacities in West Africa was acknowledged but never seen as a CGIAR task, other than by showing that top-notch scientific research leads to superior crops under favorable conditions. The example of IRRI was to be followed, and, when the opportunity came in the 1990s, it was pushed through with fervor. Such an explanation would have to discard the contradicting developments and statements presented in this chapter. Moreover, it would have to discard evidence from the history of IRRI, showing that by the early 1970s the centralized research and breeding model, including the notion of wide adaptability, was put up for debate, leading to a gradual change of IRRI’s research agenda.Footnote 59 IRRI breeders themselves advised against a centralized research agenda in Africa, stating at a conference in Nigeria in 1977 that “rice varieties should be tailor-made for specific locations, conditions and systems. So-called widely adapted varieties are probably nothing more than a reflection of a past void in local research capability.”Footnote 60 Statements like this are difficult to make chime with the course of rice research at WARDA after the 1990s. Perhaps donors and CGIAR decision-makers have had a stronger conviction regarding the powers of research excellence and science-based technologies than CGIAR researchers and other experts.

The dichotomy between the actual research work and representations of science by policymakers also played a prominent role in the life and work of Yuan Longping. As Sigrid Schmalzer has shown, Yuan’s work was embedded in wider networks of breeders, agronomists, and rice farmers across China. His role in hybrid rice breeding was largely unknown by the public until after 1976, when post-Maoist reforms started to kick in and the history of agricultural development was rewritten along the lines of research excellence and individual prestige rather than team effort.Footnote 61 Having opened this chapter with the two winners of the 2004 World Food Prize, I should end with the caution that although the prize winners no doubt have laudable merits as individual researchers, the prizes as such are poor emblems of the research traditions and history of the science of which they were a part.