Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Maps

- Introduction

- 1 Village Healers, Medical Pluralism, and State Medicine

- 2 Revolutionizing Knowledge Transmission Structures

- 3 Pharmaceuticals Reach the Villages

- 4 Healing Styles and Medical Beliefs: The Consumption of Chinese and Western Medicines

- 5 Relocating Illness: The Shift from Home Bedside to Hospital Ward

- 6 Group Identity, Power Relationships, and Medical Legitimacy

- 7 Conclusion

- Appendix One The Organization of the Three-Tiered Medical System in Rural China, 1968–83

- Appendix Two Common Medicines in Chinese Villages during the 1960s–70s

- Abbreviations

- Glossary

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Frontmatter

- Contents

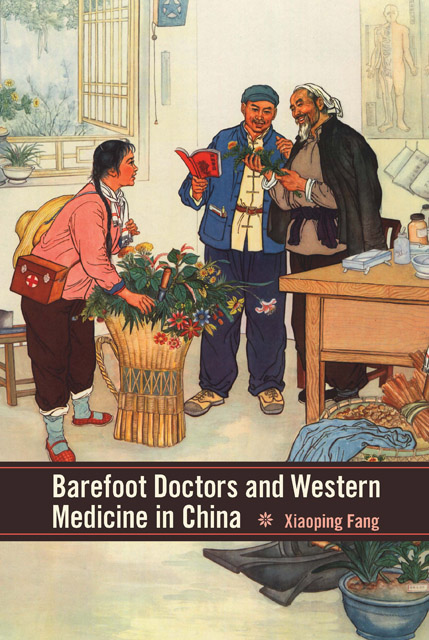

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Maps

- Introduction

- 1 Village Healers, Medical Pluralism, and State Medicine

- 2 Revolutionizing Knowledge Transmission Structures

- 3 Pharmaceuticals Reach the Villages

- 4 Healing Styles and Medical Beliefs: The Consumption of Chinese and Western Medicines

- 5 Relocating Illness: The Shift from Home Bedside to Hospital Ward

- 6 Group Identity, Power Relationships, and Medical Legitimacy

- 7 Conclusion

- Appendix One The Organization of the Three-Tiered Medical System in Rural China, 1968–83

- Appendix Two Common Medicines in Chinese Villages during the 1960s–70s

- Abbreviations

- Glossary

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

The year 1968 saw the publication of Ralph Croizier’s Traditional Medicine in Modern China: Science, Nationalism, and the Tensions of Cultural Change, which would become one of the most cited books on twentieth-century Chinese medical history. It focused on one “central paradox and main theme”: why twentieth-century intellectuals, committed in so many ways to science and modernity, insisted on upholding China’s ancient “prescientific” medical tradition. From the perspective of cultural nationalism, Croizier argued that these intellectuals were influenced by “the interaction of two of the dominant themes in modern Chinese thinking—the drive for national strength through modern science, and the concern that modernization not imply betrayal of national identity.” However, 1968 also marked the inauguration of a massive public health initiative in China that would have far-reaching consequences for the medical development of the world’s most populous country: a rural medical program inspired by the principles of revolutionary socialism and promoted nationwide. This new medical program pitted Chinese and Western medicine against one another and, more importantly, eventually determined the future of the two types of medicine in Chinese villages. This social transformation has been largely overlooked by scholars of Chinese medical history. The centerpiece of the program was the introduction of “barefoot doctors” (chijiao yisheng) into Chinese villages at the height of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76).

The barefoot doctors were members of commune production brigades who were given basic medical training so they could provide treatment and perform public health work in their home villages. They formed the lowest level of a three-tiered state medical system comprised of county, commune, and brigade levels. The concept of barefoot doctors was introduced to the public through newspaper pieces, particularly “Fostering a revolution in medical education through the growth of the barefoot doctors,” an investigative report published on September 14, 1968, in the People’s Daily, an organ of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. It described the work of barefoot doctors in Jiangzhen Commune, Chuansha County, Shanghai Municipality. On December 5, 1968, the same newspaper carried a report with the headline “Cooperative medical service warmly welcomed by poor and lower-middle peasants.” This article introduced the new cooperative medical service of Leyuan Commune, Changyang County, Hubei Province.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Barefoot Doctors and Western Medicine in China , pp. 1 - 19Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2012