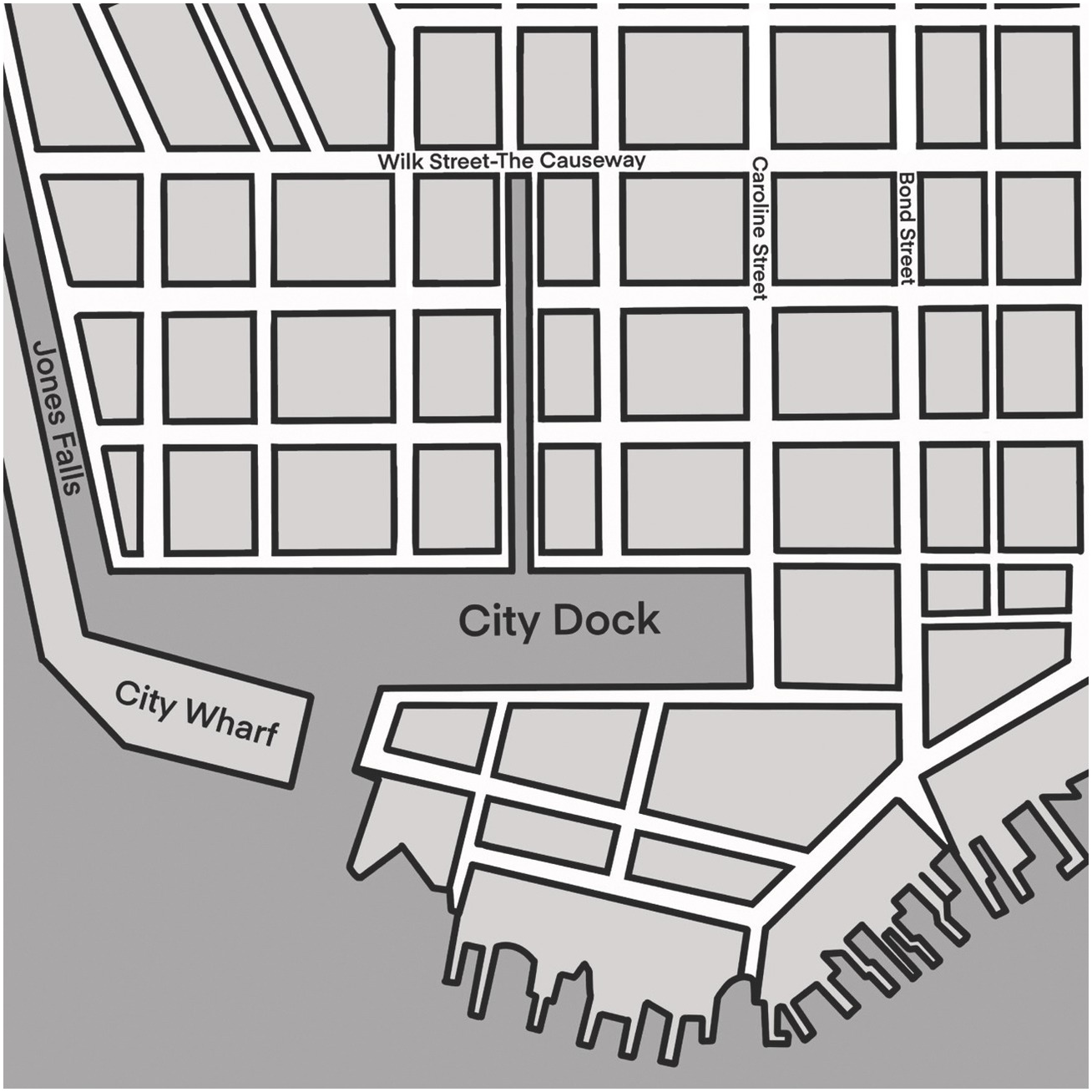

Bawdy-house keeper Ann Wilson was a fixture in Baltimore’s early sex trade. Born sometime in the 1790s, Wilson had allegedly started selling sex while in her late teens, when the city itself was barely into adolescence. In the years that followed, she became well known around town, where her stout frame and large build earned her the nickname “Big Ann” among the local sporting set. Wilson lived on a section of Wilk Street (later renamed Eastern Avenue) nicknamed “the Causeway” or “the Crossway” because of its location adjacent to a bridge over a canal that ran north from Baltimore’s deep-water harbor at Fells Point (see Figure 1.1). She may have taken up residence in the neighborhood initially as the wife of a sailor, for she often went by “Mrs. Wilson.” However, by the time she first started appearing in court dockets on disorderly house charges in the 1820s, there was no husband in her life. Tasked with raising numerous children on her own, Wilson made her living by dabbling in a variety of commercial pursuits: she offered board to seamen in port, ran betting games, sold liquor without a license, and rented rooms to women – black and white – who sold sex. Her house, which was situated just blocks from the wharves amid a smattering of taverns, groceries, and inns, was in a prime location to take advantage of foot traffic from sailors and visitors to the city. It quickly became a center of early Baltimore’s raucous, mixed-race, and loosely organized prostitution trade.Footnote 1

Figure 1.1 The Causeway vice district.

Even so, life was not easy for Wilson. At the time she lived there, Fells Point was a rough neighborhood characterized by violence and poverty. Seasonal labor patterns governed life for much of the local population, and residents’ fortunes ebbed and flowed with the pace of trade and the availability of waged work.Footnote 2 Though Wilson ran her own business, she was no more insulated from the turbulent economy of early Baltimore than others whose livelihood depended on maritime commerce. She went through periods of hardship and impoverishment, sometimes having to resort to the almshouse to sustain herself. Nevertheless, she managed over the years to scrape together enough to support herself and her children and to gain a limited degree of upward mobility. By 1840, she had expanded her enterprise to include ten female boarders between the ages of fifteen and forty-nine, an unusually high number for a brothel in a neighborhood where street and tavern prostitution predominated. Try as she might, however, she never earned enough to retire from the trade. Wilson kept her house until her death in the early 1850s.Footnote 3

Wilson’s property ownership and long tenure in the sex trade made her somewhat unusual, and yet many aspects of her life – where she lived, how she sustained herself, and how she incorporated sex work into her broader household economy – were typical of women who sold sex in early nineteenth-century Baltimore. Prostitution emerged at the same time the city did and cropped up around waterways, where it ebbed and flowed with the maritime economy, with influxes of sailors into and out of town, and with seasonal expansions and contractions in the labor market. Sexual exchange was embedded in the culture of the neighborhoods that surrounded the wharves, and women of all ages – black and white – sold sex in the streets, in taverns, at home, or in boardinghouses like Ann Wilson’s. Sex workers generally operated independently and pocketed most or all of the proceeds of their labor, but most failed to achieve more than subsistence in a trade that was still marginal and occasionally cash-poor in the first decades of the century. Sex work was a means of survival that made a great deal of sense given that early republic women had few options for supporting themselves outside a sexual connection with a man, but it was hardly a glamorous or financially rewarding means of making a living. For many, if not most, women who participated in the trade, sex work was part of an economy of makeshifts rather than a profession in and of itself.

At the time Ann Wilson entered prostitution, commercial sex was just beginning to take root in Baltimore, which was still a young and underdeveloped port city. Baltimore Town had been founded as a port in 1729, but for years after its establishment, it amounted to little more than a sleepy cluster of dwellings and a few boats along Maryland’s Patapsco River. Eventually, increased trade and the merger of the town with the nearby settlements of Fells Point and Jonestown positioned Baltimore as a growing hub of commerce. The city became an important locus of shipbuilding during the Revolutionary era, and its merchants took advantage of shipping disruptions brought about by war to expand their role in the West Indies trade.Footnote 4 By the time Ann Wilson was born, the city was on the brink of a boom period. Baltimore’s population doubled within the span of a decade in the 1790s.

In the early nineteenth century, infrastructural improvements and the growth of wheat agriculture increased the fortunes of the city and made it an entrepôt in the grain trade. Barrels of wheat flour produced in Maryland, Virginia, and points west passed from the deep-water harbor of Fells Point to Latin America, the Caribbean, and Europe. Tobacco, lumber, manufactured goods, and thousands of enslaved laborers would flow through the city to and from points around the United States and abroad. Although the trade on which the city depended faltered somewhat with the foreign relations crises of the 1790s and Jefferson’s embargo, Baltimore continued to attract visitors, residents, and commercial investment. Baltimore’s port bustled with activity, and both its fortunes and its population continued to grow, albeit unevenly.Footnote 5

Prostitution, which sprung up in many colonial cities in the eighteenth century, began to be a visible trade in Baltimore around the time of the city’s incorporation in 1796. Although Baltimore’s sex trade was considerably younger than those that existed in colonial cities like Philadelphia and New York, it resembled those trades in a number of ways.Footnote 6 Like prostitution in other urban ports, sex work in early Baltimore first emerged as a visible trade around the waterways. Court records and pardon papers contain only a few mentions of bawdy-house keeping or streetwalking in the first decade of the city’s incorporation, but visitors to the city frequently observed the connections between maritime and sexual commerce.Footnote 7 When future Pennsylvania Congressman William Darlington toured Baltimore as a young man in the summer of 1803, he wandered over to the deep-water harbor of Fells Point to admire its ships and the dense clusters of dwellings to the north of its wharves. Darlington noted that the neighborhood was “a fine place for trade” as well as a popular resort for sailors. Local shops and taverns boasted signs that catered to seafarers, including one that read “Come in Jack, here’s the place to sit at your case, and splice the main brace” (i.e., get drunk). Darlington also noted commerce of another kind. He remarked with some amusement that a section of the wharves known as Oakum Bay was “a noted place for those carnal lumps of flesh called en francais Filles de joie.”Footnote 8

Fifteen years later, a Wilmingtonian calling himself “Rustic” confirmed Darlington’s observations about Fells Point, albeit with considerably less amusement and good humor. Rustic wrote in his travel journal, “[Fells Point] is the rendezvous for all the heavy shipping … There were several fine ships at anchorage: some just arriv’d and others about to embark. But it has the appearance: & I was enform’d was a place of great dissipation, prostitution & wickedness.”Footnote 9 By the time Rustic came to Baltimore, the Causeway where Ann Wilson lived and worked had become the city’s main site of sexual commerce.

Early prostitution’s roots in maritime communities were a product of the mobility, precariousness, and unique cultures of labor that characterized life for sailors and their families in the early republic. Although prostitution changed a great deal over the first half of the nineteenth century in terms of its forms and labor arrangements, one point of consistency was that it thrived when there were high rates of population mobility and large numbers of women struggling to earn a living in the paid labor market. Maritime communities had both of these characteristics – and in exaggerated form – before the rest of the city developed them. The neighborhoods along Baltimore’s wharves were always in flux. Labor patterns were seasonal, with commerce and employment opportunities peaking during the warm months when the harbor was easily navigable and trade was steady. During that time, it was not unusual for men who labored at sea to leave for weeks or months at a time on voyages along the coast or around the Atlantic. Their absences left their wives or female family members to manage households and raise children on their own, often without the benefit of their Husbands’ wages, which might be delivered only at the end of a voyage or delayed in reaching home. Fells Point, which Darlington and Rustic identified as a center of the early sex trade, had an unusually high number of female-headed households. Because maritime labor was dangerous and often unpredictable, the women who kept those households lived with the uncertainty that they might never see their husbands, fathers, or male relatives again once they boarded their ships.Footnote 10 Women had to fend for themselves for long stretches of time.

Sailors’ wives, like other women who were forced to labor for wages, struggled to make ends meet in an early republic economy that provided them with limited economic opportunities. As Jeanne Boydston argued in her classic study Home and Work, the decades following the Revolution marked a period of labor transition in which it was increasingly assumed that women were – and should be – nonproductive dependents of men rather than workers who made contributions to the household economy.Footnote 11 The waged labor market reflected this shift. Work for women was never lacking in Baltimore; indeed, local newspapers in the early years of the city were filled with advertisements from employers seeking housemaids and other domestic workers, and women provided much of the labor in the spinning and needle trades. However, employers justified paying women very little on the assumption that women were merely supplementing a household wage rather than supporting themselves independently. Most of the jobs that were open to women paid wages that were below the level required for subsistence. Domestic work, which was by far the most common occupation, produced scarcely enough income for a worker to support herself, much less a family (the existence of which might prevent her from gaining domestic work in the first place). Many women participated in an economy of makeshifts in which they made ends meet through a variety of seasonal and often cobbled-together economic pursuits. These included opening their houses to boarders, cooking for and selling alcohol to lodgers and sailors, doing housework for wealthier families, scrapping, checking into the almshouse to labor in exchange for food and shelter, and at times participating in sex work.Footnote 12

Sex work for women struggling to get by was part and parcel of an early republic economic structure in which most women had to attach themselves sexually to men in order to survive. Sex workers in maritime neighborhoods found themselves with a ready clientele during the warm months. In the early years of the city, sailors drove much of the demand for sexual services. The nature of maritime labor meant that they were without women for weeks or months at a time, and the uniqueness of their work gave rise to specialized subcultures of leisure, masculinity, and sexuality. As Paul Gilje has argued, sailors often embraced a rough and ribald concept of masculinity that was focused on strength, bravery, and virile conquest of women. At the same time, many also idealized the home and the women they left behind as they embarked on long voyages.Footnote 13 Seafarers who came into port often sought out both domestic and sexual modes of interaction with women residing on shore, and many found it most easily through commercial transactions. Cities became sites of potential for sexual and ribald fun and short-term romance for sailors who arrived in port with a month’s pay or more in their pockets.Footnote 14

Prostitution became enmeshed in the broader network of dockside businesses that catered to sailors and local workers whose livelihoods depended on trade. Boardinghouses that provided shelter, washing, food, and other domestic services and taverns that provided drink and entertainment were both favorite sites of solicitation for jacks looking for female companionship. This sale of sex and other services was part of what historian Seth Rockman referred to as the “commodification of household labor,” a process that took place in the early nineteenth century as mobile male populations turned to commercial exchange for services that might otherwise be provided by wives.Footnote 15 Some sailors sought out women for the purposes of quick, anonymous sexual exchanges or short flings, while others paid women to act as surrogate partners who performed many kinds of labor for them, including cooking, laundry, and general companionship. Arrangements sometimes blurred the boundaries between purely commercial and genuinely affectionate. Notably, women who acted as domestic surrogates relieved sailors of having to perform “feminine” tasks, like sewing and mending, that they would be expected to perform at sea and thus allowed them to experience – however briefly – a more traditionally gendered labor regime.Footnote 16

In Baltimore, as in other cities at the turn of the nineteenth century, selling sex was not an especially lucrative trade for the women who participated in it. Although it generally paid better than other forms of work open to women, the value of sexual labor could and did fluctuate with the economy. Following the specie contractions of the 1790s, Baltimore’s economy was so cash-poor that some women who sold sex did so on a virtual barter system, as had been common in the early modern period. When William Darlington observed the “filles de joie” in Fells Point in 1802, he noted that they were not paid in cash. The area that they operated out of had been nicknamed Oakum Bay on account of the fact that sex workers who labored there exchanged sexual services for “rope yarn and old cables” from sailors.Footnote 17 In addition to not being especially valuable, old rope yarn and cable also required considerable labor in the form of spinning to transform them into a salable product. For the women who were willing to trade sex for such meager compensation, prostitution was less a means of getting ahead economically than a desperate measure to avoid abject poverty.

Even as cash flowed more freely over time, women who sold sex continued to struggle to make ends meet. The embargo of 1807 and the prohibitions on wheat trading during the War of 1812 hit Baltimore’s young, maritime-oriented economy hard and caused the shipping trade to stagnate. The sex trade declined with it. Just a few years after Baltimore recovered from the economic devastation wrought by these trade prohibitions, the Panic of 1819 heralded a new economic depression. The flow of sailors to the Causeway’s brothels and taverns slowed, along with trade as a whole, and high unemployment rates meant that fewer men had money to spend on sex. Circumstances were bad enough that even women who owned their own establishments suffered. In the winter months of 1820–21 and 1821–22, when trade was especially stagnant because of cold weather and freezes, Ann Wilson found herself on the verge of impoverishment. As many women did in the winter months, Wilson begged admission to the almshouse, which provided her warm lodgings, regular food, and treatment for venereal disease during the slow period for commercial sex. She checked herself out in the spring, when business was likely to be better.Footnote 18

It would take years for the growing availability of bank notes and other paper money and the expansion of wage labor to improve compensation for sex work, and even that could not relieve seasonal doldrums entirely. Women in the sex trade had such narrow economic margins that they were often forced to resort to charitable facilities and hospitals when illnesses rendered them unable to work, even temporarily. Records from the Marine Hospital and the almshouse list over a dozen sex workers who entered those institutions’ medical wards, most of them pregnant or visibly infected with venereal or tubercular diseases.Footnote 19

Because the early sex trade was part of the makeshift economy, it was deeply integrated into the culture and social life of Baltimore’s poor. Relatively few women were professional prostitutes in any sense of that term, and prostitution in East Baltimore’s maritime communities would maintain this informality through much of the nineteenth century. Sex work was loosely organized and largely conducted on an individual basis, and many women moved in and out of sex work in their youth and throughout their lives as need dictated. This behavior, while not entirely without social repercussions, was more accepted in poor neighborhoods than it was in more genteel ones. Laboring people did not always approve of sex outside marriage (although their conceptions of marriage and what it entailed were often flexible), but they understood better than their elite counterparts that sex was often transactional, be it in the context of prostitution or in a woman marrying a man for his wages. As such, they did not usually attach a permanent stigma to women who worked as prostitutes, nor did they insist on clear boundaries between the illicit world of the sex trade and the more licit world of everyday life and commerce. In neighborhoods like Fells Point, the children of brothel keepers attended Sunday school at the local church alongside the children of more respectable families, and young boys were allowed to play in the streets in front of houses of ill fame. Women who sold sex in their youth married and started families later. The world of sexual commerce was porous, casual, and integrated into the social fabric of many waterfront communities.Footnote 20

The casual nature of sex work meant that it was a survival strategy open to women from a variety of age groups and life circumstances. Many sex workers in East Baltimore, including Ann Wilson, were widowed, separated, or married women with absent husbands who were selling sex as a means to support their families. Mary Bower, who lived not far from Wilson’s dwelling in Fells Point, performed sex work to keep her household afloat. At age thirty-eight, Bower lived with her two sons, aged seventeen and nineteen. Although both of her sons worked, Bower had a difficult time maintaining the household. In addition to taking a young ship carpenter and his wife as boarders, Bower gave her occupation to the census taker as “lady of pleasure.”Footnote 21 Although the bulk of women involved in prostitution were younger than Bower and more casually involved in the trade, familial situations like hers were common. Up to a quarter of women who participated in sex work in the early republic were married, and economic hardship ensured that some continued to perform sexual labor until they were advanced in age. In 1814, a woman named Ann France accused a farmer named Thomas Potter of raping her after she visited his mother’s house in search of liquor. Pardon requests submitted on behalf of Potter described France as “a Notorious drunkard, a dirty, hackneyed prostitute of seventy-one years of age.”Footnote 22

Other women were unmarried and barely more than girls when they took up the trade, often in an attempt to escape difficult or restrictive home lives. Just as wives in the early republic were bound to their husbands by law and by unequal labor opportunities, daughters were bound to their parents, specifically to fathers who acted as family patriarchs. They were expected to live at home until marriage, work in support of the household, and be obedient. And yet many young women yearned for a degree of independence from their families, parental control, and the drudgery of menial labor they performed as part of their domestic duties. Some married early, while others turned to sex work to escape the domestic realm in the period between childhood and marriage. As Clare Lyons argued, prostitution was sometimes a “sexual lifestyle” for young women, one that allowed them to engage in sexual license and pleasure while also supporting themselves.Footnote 23 Some young women seemed to relish the independence and opportunities to meet men that prostitution provided, and they formed short-term relationships with their clients that were intimate as well as commercial. Other women entered prostitution in a bid to escape the violence that characterized life in their households. Such was the case for Elizabeth Shoemaker, an eighteen-year-old Fells Point resident who had a difficult relationship with her father and his wife. Following the death of Elizabeth’s mother, her father had married a woman who resented and abused Elizabeth. In protest, Elizabeth ran away from home and resorted to “one of those sinks of Iniquity,” where her stepmother complained that she spent her “night[s] in riot and debauchery.”Footnote 24 Another young woman, Elizabeth Miller, ran away to a house of ill fame, because her father and mother forced her to scrap during the day and beat her if she did not return with sufficient money. Life in a house of ill fame, she said when summoned before a justice of the peace by her father, was preferable to laboring on the streets and suffering abuse.Footnote 25

In addition to being diverse in terms of the age of its participants, early Baltimore’s sex trade was racially mixed. Baltimore was a slave city. In 1790, enslaved people made up approximately 9 percent of its population, a statistic that excluded the large number of men and women who migrated seasonally between Maryland’s wheat and tobacco fields and urban work.Footnote 26 In the wake of two decades of manumissions that followed the Revolution, the city became home to a sizable free black population, which would grow into the largest in the country by the midcentury. Because the majority of enslaved laborers in the city were domestic workers and because freedwomen were more apt to work in nonagricultural employments in the city than freedmen, Baltimore’s black population was disproportionately female. Between 1810 and 1820, the number of free black women residing in Baltimore doubled, and black women came to outnumber black men in the city by a ratio of three to two.Footnote 27

Black women faced many of the same challenges that white women did in early Baltimore’s economy, but their difficulties were exacerbated by personal histories of enslavement, uneven sex ratios among the city’s black community, and restrictions placed on them as a result of their race. Many of the freedwomen who arrived in Baltimore were accustomed to agricultural labor and may have lacked skills like knitting or needlework that were trained into their white counterparts from the time they were children. Their inexperience, coupled with some householders’ preference for white domestic servants, may have stymied them as they attempted to compete for paid employments.Footnote 28 Meanwhile, the dearth of black men in the city and legal and social intolerance of interracial unions meant that many black women could not marry or otherwise form households with men who might contribute wages or economic support. Although many black women found alternative means of surviving the early republic’s harsh economic climate by forming extended kinship networks, taking washing, and huckstering, some followed a path common among their white counterparts and turned to selling sex to supplement their earnings.Footnote 29

Black and white sex workers, like the black and white populations of the city as a whole, lived and labored alongside one another. Baltimore was similar to most Southern cities in that it was not residentially segregated in the first decades of the nineteenth century. Because black men and women so frequently performed domestic labor for white Baltimoreans, it was common for city neighborhoods to be racially integrated, albeit through residential arrangements that reflected social inequalities. Black laborers and their families often lived in alley houses that abutted white residences, or they even (in the case of domestics) resided with white families in more affluent areas. As historian Seth Rockman has noted, Baltimore’s labor market was similarly integrated from the 1790s until the 1830s. Black and white men worked together on public improvement projects around the city as well as in a number of other unskilled or semi-skilled jobs that did not require apprenticeships, and local employers treated white and black women as interchangeable when it came to domestic service. The maritime trade in Fells Point and Old Town drew both black and white workers, who labored together – not always harmoniously – as sailors, ship caulkers, and day workers. In some cases, they were even paid the same wages. It would not be until the 1830s that growing tensions over slavery, fears of slave revolt, and hardening racial ideologies would bring about the privileging of white laborers and the exclusion of black workers from trades.Footnote 30

Just as the general labor market was racially integrated in early waterfront communities, so too was the market and the customer base for sexual labor. Early spaces and zones of sexual commerce were as racially mixed as the rest of city life. Black sex workers mingled with white ones on the wharves or in taverns, brothels, and bawdy houses that catered to white, free black, and enslaved clientele. Ann Wilson’s establishment was notorious for both renting rooms to black sex workers and allowing interracial sex. Similarly, James Dempsey’s disorderly house on Fleet Street was known for attracting what newspapers referred to as an “abandoned set of loafers and prostitutes, black and white,” as well as a mix of free and enslaved male patrons.Footnote 31 When police raided Dempsey’s house in 1839, they found among its patrons an enslaved man named Wilkey Owens, who, presumably, was one of the many enslaved men living in Baltimore who was allowed to hire out his own labor and keep a portion of his wages.Footnote 32 Most of the brothels on Brandy Alley, which subsequently became Perry Street, attracted similar demographics. An 1839 advertisement for a fugitive slave, Henry Kennard, noted that Kennard was “well known among the negro haunts in Brandy Alley.”Footnote 33 Despite city officials’ paranoia about black gatherings and suspicion of white and black city residents socializing with one another during their leisure time, raucous establishments that catered to neighborhood residents of both races were common. Gambling, dancing, drinking, and prostitution were all popular forms of recreation in East Baltimore’s alleys.

In some cases, black men and women even managed to own or supervise their own bawdy houses, though limited economic resources and the restrictions placed on black Baltimoreans made this comparatively rare. For a time in the 1830s, two free black women named Juliana Bosley and Mary Benson kept rival houses located next to one another in Fells Point.Footnote 34 More commonly, black women managed houses on less centrally located streets or small alleys in Old Town. Iby Tomlinson, a black woman living in Dutch Alley, owned a “negro brothel” that attracted white clientele, and several similar establishments existed in Salisbury Alley.Footnote 35 One of these houses, kept by Margaret Perry, explicitly catered to white men in the hopes of cashing in on what historian Edward Baptist called the “erotic haze” that surrounded black and “mulatto” women in the minds of white Southerners. Although Perry was light-skinned enough that she appeared to be of “Anglo-Saxon” origin, newspapers claimed that she “gloried in laying claim to affinity to the African race.” Forgoing the significant legal and social privileges that came with being read as white, Perry specifically described herself as a “yellow” woman in her business dealings. While this may have been a personal decision, it also had an eroticized appeal in a city like Baltimore, where slave trading firms like Franklin and Armfield were well known for purchasing light-skinned enslaved women in order to sell them as sexualized commodities.Footnote 36 In 1837, when Perry’s neighbor, Caroline Trotter, accused her of keeping a disorderly house, Perry had her lawyer read a statement in open court claiming that Trotter was a fellow sex worker who was bitter that gentlemen’s preferences for Perry had reduced Trotter to performing sewing work and fixing up ball gowns for Perry’s “lady” visitors.Footnote 37

Sex between black sex workers and white men and vice versa was common in Baltimore’s early prostitution trade and, indeed, continued to be common in East Baltimore until the eve of the Civil War. In 1839, police arrested a fifteen-year-old white girl named Mary Jane Long in a house on Brandy Alley that was “frequented by blacks as well as whites” and sent her to the almshouse.Footnote 38 An anonymous 1842 chronicler of the Causeway’s vice district noted, with no small degree of titillation, that it was possible to enter some brothels and “view the Circassian and sable race beautifully blended together, and their arms intermingled so as to form a lovely contrast between the alabaster whiteness of the one, and the polished blackness of the other.”Footnote 39

Brothels, in general, were less common in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries than they were in later decades, and those that did exist differed from the establishments that would exist later in the nineteenth century in terms of their level of commercialization and specialization. In keeping with prostitution’s integration into poorer neighborhoods in the early republic, sexual commerce was not yet spatially separated from places of general resort, work, or commerce for laboring people. The establishments where sex workers conducted their transactions – what were called brothels and bawdy houses at the time – were usually not devoted entirely to sexual commerce. Much of the sexual solicitation that took place in early Baltimore happened in the wharves, in the streets, or in taverns that catered to maritime laborers and other workingmen. Women and their clients carried out their sexual transactions in rooms rented from boarding houses, inns, or taverns if they could not do so within the home. The casualness of the trade and its spatial overlap with other forms of commerce would persist in East Baltimore through the Civil War period.

Taverns were particularly popular venues for prostitution. Local drinking spots were important social and political sites in the Revolutionary era and the early republic, and they were usually masculine spaces.Footnote 40 However, low-end taverns in waterfront neighborhoods attracted a mix of patrons, black and white, men and women. For the “disreputable” women who composed the majority of taverns’ female visitors, solicitation in indoor spaces carried less risk of arrest than more visible, public means of solicitation like streetwalking. The constant stream of male patrons into Causeway taverns provided a ready clientele for sex workers, and taverns also gave women the opportunity to have men buy them drinks or provisions in addition to paying them for sexual services. Tavern keepers, for their part, welcomed the arrangement as a boost for business. The Viper’s Sting and Paul Pry, a short-lived sporting paper published in Baltimore in the 1840s, noted that mutual arrangements between prostitutes and tavern keepers were common. Its writer commented that the eastern part of the city was dotted with what appeared to be “well-kept taverns, while in reality they are vile brothels, frequented by the lowest prostitutes.”Footnote 41 The Causeway alone featured several taverns that regularly rented rooms to sex workers, and Old Town’s L Alley and Pitt Street were host to several grog shops that were known to attract rowdy and bawdy clientele. One commenter complained that a groggery in Pitt Street (later, Fayette Street) drew a crowd that caused the neighbors to be “disgusted and abused, day and night, with the obscene language and drunken orgies of a horde of wretches.”Footnote 42 A German immigrant whose fourteen-year-old daughter had run away from home lamented the presence of such havens of vice in the city. Suspecting that her daughter was selling sex, the woman initially “sought for her in a stew kept by Mary Pearson.” Not finding her there, the mother checked a local tavern, where she discovered her seated at the bar, attempting to attract the attention of men.Footnote 43

Boardinghouses and inns, particularly those that catered to sailors, were also common brothel sites. The areas around Fells Point and the harbor were dotted with small lodging establishments whose keepers depended on the traffic of maritime laborers in and out of the harbor for business. Some of these inns and boardinghouses allowed men to bring women back to their rooms, while others boarded sex workers as part of a larger strategy to extract money from their male patrons. Ann Wilson’s brothel, which boarded several women, doubled as a sailor’s boardinghouse. Similarly, James and Ann Manley, who kept a small travelers’ and sailors’ hotel on the Causeway in the 1850s, were in the habit of renting some of their rooms to sex workers. The Manley’s neighbor, Mary A. Keul, employed the same business model. At the time of the 1860 census, Kuel kept a hotel that had four female boarders between the ages of nineteen and thirty-three, an arrangement that (viewed in light of the Causeway’s reputation) suggested that she was running a brothel.Footnote 44 Baltimore’s Salisbury Street, Brandy Alley, and Guilford Alley also featured boardinghouses that were well known as resorts for “debauchery.”Footnote 45

In many cases, sex work in boardinghouses was part of a larger economy rooted in fleecing sailors of their earnings and keeping them in cycles of debt. Many businesses that catered to sailors were owned by “land sharks,” who made their livings by exploiting maritime laborers. Sailors were vulnerable to exploitation because their rowdy reputations and unfamiliarity with the cities they visited limited their boarding options, and their tendency to be paid in lump sums in advance or following voyages meant that they often had cash on hand. Many boardinghouse keepers intentionally overcharged sailors for board and drink and kept women on hand in order to encourage them to spend their money and prevent them from straying from the establishments to seek entertainment or sex. In some cases, sea captains even colluded with land sharks to ensure that sailors spent all of their money and advances and were thus driven back to sea to resolve their debts and earn their living. Sexual commerce thus became part of a strategy for ensuring a ready supply of laborers to perform the difficult and often miserable work of securing the passage of goods across the Atlantic.Footnote 46

Sex work was integrated into illicit, informal, and illegal economies outside boardinghouses as well. Disreputable taverns and brothels in the early republic were often sites of theft and of traffic in illicit and stolen goods. Many sex workers in low-end bawdy and assignation houses, particularly those that lined Chestnut (also called Potter) Street in Old Town, supplemented their income from sex work and domestic labor by stealing from their clients. Though there is little evidence that the kind of sophisticated panel housesFootnote 47 that existed in cities like New York existed in antebellum Baltimore, court and newspaper records contain a number of examples of East Baltimore sex workers who took advantage of men when they were in flagrante delicto or sleeping. Caroline Davenport, keeper of a brothel on the Causeway, was charged in 1837 with stealing a pocketbook from Captain George Hayden, a visitor to her house. The Sun’s wry commentary – “We forbear, at present, to state the circumstances under which the robbery was perpetrated” – left little doubt that Hayden had been in a compromising position at the time of the theft.Footnote 48 In a similar incident, Harriet Price, the long-time African American keeper of a house in Old Town, was charged with stealing a breastpin from one of her male clients, John Roberts.Footnote 49 Though both Davenport and Price faced legal penalties for their actions, many crimes like theirs likely went unreported by men who were not in the city long enough to pursue prosecution or who were loath to notify the police – and, by extension, the press – that they patronized brothels. So long as women avoided stealing from local men who composed a regular clientele, they were relatively free to supplement their incomes by stealing from travelers and visiting seamen.

The prevalence of theft in East Baltimore’s houses had much to do with the poverty of the neighborhood and the lower profit margins of selling sex to sailors and laboring men. At times, competition for resources grew so intense that casual sex workers abandoned all pretense of artfulness and outright assaulted and robbed visitors to their neighborhoods. In 1846, Mary Brown, Ellen White, Ann White, and Julia Ann Stafford were charged with robbing William Johnson of four or five hundred dollars. Johnson, who was not from Baltimore, had wandered into Wilk Street without knowing its reputation. One of the women threw a stone at Johnson’s head, stunning him. The rest surrounded him, hit him over the head with a bottle, and picked his pocket in the scuffle. By the time Johnson realized that he had been the victim of theft, the women had already scattered and stashed the stolen money in one of the local houses. Despite a thorough search of the area, police never recovered it.Footnote 50

The money may have disappeared because some women in East Baltimore’s sex trade supplemented their earnings from selling sex by fencing stolen goods, laundering illegitimate or counterfeit money, and acting as semi-licit pawn brokers. While early Baltimore had numerous “legitimate” or semi-legitimate pawnshops that provided loans to poorer members of the community, such shops did not serve all city residents equally. By law, pawnshops could not serve enslaved people without explicit permission from their enslavers, and some explicitly refused to accept goods from black Baltimoreans on the grounds that the property was assumed to be stolen.Footnote 51 Proprietors of early sex establishments tended to be more willing to serve black patrons and to assume the risks associated with taking goods of questionable provenance, and their businesses became destinations for marginalized city residents who required loans or payments. Many women had frequent contact with local watchmen and courts as a result of their activities. Harriet Price, one of Baltimore’s few black sex establishment keepers, appeared in court no fewer than twelve times on various charges, two of which were related to possession of items alleged to have been stolen. In one instance, Price was alleged to be holding a gold watch taken from Henry Rowe of Alexandria, VA. In another incident that did not result in her arrest, police searched her house for stolen merchandise after seventeen-year-old Frank Bowen was arrested for stealing fancy goods from Boury’s on Baltimore Street, where he worked as a porter. Bowen told the magistrate that he had taken the goods to Price’s house, where authorities eventually recovered them.Footnote 52 Price was also partnered for a time with a local thief named Giles Price, who was eventually sold into term slavery in Georgia after he was arrested outside Harriet’s brothel with stolen money on his person.Footnote 53 Harriet Price was not alone in her attempts to supplement the proceeds of prostitution with the discounted purchase of stolen goods or with theft. When George Cordery stole a lot of spermaceti candles from the docks, he sold part of his loot to Sarah “BlackHawk” Burke, who operated a well-known brothel north of the harbor.Footnote 54

Brothel keepers’ and other sex workers’ practice of trafficking in stolen goods put them at risk of arrest and incarceration for theft, but that was just one of several legal hazards that accompanied sex work in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Although exchanging sex for money was not technically illegal in early Baltimore, local authorities could, and did, police prostitution as a public nuisance under the common law. They did so often as part of what historian Jen Manion has described as a post-Revolutionary project by elites to reestablish social hierarchies by curtailing rowdiness and sexual misconduct and insisting that men and women conform to their “proper” social roles.Footnote 55 Prostitution as it existed in the early nineteenth century not only promoted forms of sexual licentiousness incompatible with good republican citizenship but also violated a gendered order that insisted that women’s place was in the home rather than in streets or taverns.Footnote 56 Women who labored as streetwalkers or sold sex in public places were therefore at constant risk of being hauled into court for disorderly conduct or, more commonly, vagrancy.

Following the Revolution, paranoia about rapid urban growth fueled concerns among elite Baltimoreans that the municipality was being overrun by idle, disorderly, and “unworthy” paupers, which ensured that local ordinances and state laws concerning vagrancy were especially harsh. In 1804, the Maryland legislature passed a law specifying that “every woman who is generally reputed a common prostitute … shall be adjudged a vagrant, vagabond, prostitute or disorderly person” and allowing accused vagrants to be confined at hard labor in the almshouse for two months.Footnote 57 In 1811, Baltimore Mayor Edward Johnson complained to state officials that the 1804 law was insufficient to prevent the city from being overrun by dissolute persons and beggars. The state legislature responded by passing an even stricter vagrancy law that stated that persons in Baltimore City deemed vagrants or vagabonds could be sentenced to a year in the newly constructed state penitentiary.Footnote 58

Enforcement of the vagrancy statutes could be vigorous and devastating for sex workers and other poor women.Footnote 59 In 1816, during a peak period of paranoia over vagrancy, Baltimore’s Court of Oyer and Terminer heard sixty-two separate vagrancy cases. About a fifth of these resulted in the offenders’ convictions and remand to the penitentiary for a year. While it is not clear how many of the accused “vagrants” were sex workers, it is the case that over 70 percent of those charged with vagrancy and three-fourths of the 186 people sent to prison for the offense during the period when the 1811 vagrancy law was in force were women, mostly Maryland-born, white, and in their twenties.Footnote 60 In prison, they were forced to labor at “wool picking,” sewing, or the arduous, unpleasant task of washing for the duration of their confinement.Footnote 61 After 1819, the state rescinded the harsh vagrancy law requiring confinement in the penitentiary and returned to the earlier practice of sending women to the almshouse for months of labor. Although this was a less severe punishment – among other things, the almshouse was easy to escape – women who faced it were given virtually no due process rights or rights to trial. Under the more lenient law, vagrants were simply called before a magistrate – often at the complaint of a single witness and without the benefit of counsel – and remanded to labor at the magistrate’s discretion. The constant threat of being arrested and incarcerated for months at a time must have weighed heavily on women who barely made their living soliciting sailors or cruising local taverns for clients.Footnote 62

Women who kept sex establishments had more legal protections on the basis of their access to property, but they too faced the possibility of arrest, high fines, or even incarceration. Keeping a disorderly or bawdy house was a misdemeanor offense that entitled the accused to a jury trial if she or he so chose, but the fines on conviction were high, especially in the late eighteenth century. In 1789, Elizabeth Cowell was summoned to court on the complaints of three witnesses, John and Elizabeth Winchester and James Clemments, who claimed that she kept a disorderly and bawdy house. The court fined her the staggering sum of £30 and required her to post an additional £50 security for her future good conduct.Footnote 63 By the first decades of the nineteenth century, penalties for the offense became less severe, but prosecutions grew more frequent. In 1813 and 1816 fifty-five persons were charged in the Baltimore County Court of Oyer and Terminer with keeping a bawdy or disorderly house – the latter an umbrella charge that encompassed gambling dens, places of resort for loud crowds, or illegal liquor dens, as well as brothels.Footnote 64 Only six of the individuals charged with the offense were actually convicted, and most of them were sentenced to much smaller fines than the one that had befallen Elizabeth Cowell. However, even the more modest $10 fine that was typically issued in these cases exceeded the financial abilities of some defendants. Some defendants went to jail for weeks or months. Black defendants, who had more limited access to financial resources than white ones, tended to remain in jail the longest. They also faced the threat of a more serious loss of liberty if they could not raise the revenue to pay the fine and their jail fees within a sufficient amount of time. In 1813, Betsey Hawlings was fined $10 for keeping a disorderly house and committed in default of payment. Although Hawlings was not listed in the court docket as black (court clerks were often careless about such distinctions in the early period), a notation on her case read “committed & sold,” which suggests that she was likely a free black woman who was sold into slavery as a result of her conviction.Footnote 65

Punishment for the keepers of disorderly houses grew more severe after 1817, when the Baltimore County Court of Oyer and Terminer was renamed the Baltimore City Court and tasked with hearing only those cases that originated from within municipal boundaries.Footnote 66 Chief Justice Nicholas Brice and his compatriots on the court raised the standard fine levied on those found guilty of keeping a disorderly house from the previous amount of $5 to $10 per offense to $20 plus court costs. In some cases, court costs could exceed $10, and any defendant who failed to pay the fines and costs promptly was incarcerated in the city jail.Footnote 67 Brice and his fellow justices also issued harsher sentences to certain defendants whose establishments they deemed particularly offensive to public morals. Unis Miller, who was found guilty of keeping what was apparently a particularly raucous disorderly house on Caroline Street, was fined $50 and costs, sentenced to six months in jail, and ordered to remain in the institution until she paid her fine.Footnote 68 Five other women brought to court around the same time as Miller were sent to jail for between two and three months.Footnote 69 Incarceration was an especially harsh punishment, as it required women and men who kept bawdy houses to spend weeks living under unpleasant conditions and losing out on the money they might earn from their establishments. The measures that Brice and his compatriots used against brothel keepers were intended to be suppressive.

Even as late as the 1820s, sex workers’ rewards for shouldering and surviving the risks that accompanied prostitution in East Baltimore’s casual trade were usually meager and limited to basic subsistence. Most women left the trade after a few months, married, and settled into other forms of work. Those who remained could expect to cycle in and out of prostitution and often in and out of the city’s workhouses and public medical facilities. Even brothel keepers like Ann Wilson, who were more fortunate than most sex workers in that they owned property, rarely earned upward mobility for themselves; their best chance was usually providing it to their children. In Wilson’s case, she kept her son at home with her for protection but sent her daughters away to school so that none of the stigma of her trade would attach to them. Her money, divorced from the circumstances of its earning, afforded her daughters a degree of privilege, and – according to some sources – allowed them all to attract respectable husbands. George Konig, another Causeway brothel keeper and member of a Democratic political gang in the 1840s and 1850s, leveraged his political connections, as well as the money he and his wife, Caroline, earned through brothel keeping to launch his son into a political career. George Konig Jr. became a United States congressman.Footnote 70 Neither Wilson nor Konig Sr. ever escaped the trade.

In Fells Point and other East Baltimore neighborhoods, the sex trade would remain informally organized, oriented toward sailors and other laboring men, and integrated into the local tavern and boardinghouse economy through the Civil War period. Mobility, seasonal labor patterns, and economic precariousness continued to characterize life in the Causeway, even as the city as a whole matured and developed some of the hallmarks of refinement that had been largely absent in its early days as a port. By the 1820s, however, the sex trade would begin to expand beyond maritime neighborhoods as the transience and anonymity that characterized life along the wharves came to characterize urban life as a whole. As the trade gradually took root at the outskirts of commercial and leisure districts, it would follow a path common to many industries and commercial ventures and adapt more centralized, specialized labor arrangements. The world of commercial sex that Ann Wilson had helped to make would be a much different world from the one that evolved in the Western part of the city.