Book contents

6 - Truth, objectivity and knowledge

Summary

Introduction

Philosophers, no less than others, take comfort in familiar labels. To discover that someone is a physicalist or a compatibilist or a Platonist is to be instantly situated philosophically with regard to that person, and, while such familiarity may well breed contempt, it also orients and, in orienting, comforts. Williams, however, in this as in so many ways, provides little comfort; that is, his views either resist being labelled entirely, or invite only radically attenuated application, particularly in the realm of ethical philosophy. Not surprisingly, Williams's ethical scepticism and anti-theoretical tendencies militate against ascribing to him obvious first-order or normative positions, as his critique of others' answers to Socrates' question (how should one live?) effectively camouflages his own. But what about his positions on second-order, or more meta-ethical, issues? However difficult it may be to label Williams's own custom-made alternative to, say, utilitarianism or Kantianism, surely he must embrace certain ready-to-wear views concerning its philosophical underpinnings; surely he must embrace certain familiar metaphysical and epistemological commitments; and surely these can be labelled.

Metaphysically, such commitments typically invite the labels “realist” or “anti-realist”, as they assert or deny, as Williams roughly puts it in Morality, “that thought has a subject matter which is independent of the thought” (Williams 1972: 36). They are no doubt best construed along a continuum of gradually intensifying avowals of ethical objectivity; indeed, objectivity constitutes the playing field upon which realists and anti-realists butt heads.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

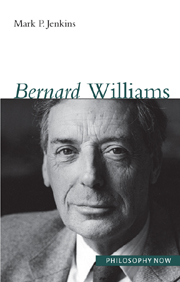

- Bernard Williams , pp. 121 - 148Publisher: Acumen PublishingPrint publication year: 2006