On the first anniversary of Independence in August 1948, with tension mounting between India and Pakistan over the future of the Princely State of Hyderabad (Deccan) and its Muslim minority population,Footnote 1 the Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru broadcast to the nation from the same spot in Delhi where he had delivered his ‘Tryst with Destiny’ speech twelve months before:

Free India is one year old today. But what trials and tribulations she has passed through during this infancy of her freedom. She has survived in spite of all the perils and disaster that might well have overwhelmed a more mature and well-established nation … We have to find ourselves again and go back to [the] free India of our dreams. We have to re-discover old values and place them in the new setting of [a]free India. For freedom brings responsibility and can only be sustained by self-discipline, hard work and [the] spirit of a free people.

Nehru then concluded with the following impassioned ‘call to arms’:

Let us be rid of everything that limits us and degrades us. Let us cast [off] our fear and communalism and provincialism. Let us build up a free and democratic India where [the] interests of the masses, our people, has always the first place to which all other interests must submit. Freedom has no meaning unless it brings relief to these masses from their many burdens. Democracy means tolerance, tolerance not merely of those who agree with us but of those who do not agree with us.Footnote 2

As this attempt in the summer of 1948 to enlist fellow Indians in a ‘war’ to resolve some of the myriad problems caused by Partition underlines, all new regimes create, revive and mobilize political symbols – both material and rhetorical – as a means of consolidating power and simultaneously propagating visions of shared citizenship. Politicians and governments in Pakistan and India in the immediate post-Independence period followed distinctive strategies in their promotion of national iconographies and views of the ideal citizen.Footnote 3 But how these were re-circulated – in different localities, by a range of different institutions and movements, and sometimes through the spontaneous response to them by ‘crowds’ – affected their meaning and impact over time. Furthermore, their transmission was far from passive thanks to the ways in which such symbols can themselves be transformed as a result of precisely this kind of circulation taking place at different social and spatial scales.Footnote 4 This opening chapter, therefore, begins our exploration of postcolonial citizenship by considering how far – for India and Pakistan during their early years – the process of ‘making citizens’ was also about consolidating the unitary state in ways that could often allow each country to emulate the other, despite contrasting contexts.

Following Independence and Partition, politicians supported by bureaucrats at the centre, whether they were located in the new capital cities of Delhi or Karachi, expressed a clear desire to manage or contain regional difference and to promote a strongly centralized unitary form of government. In this, irrespective of location, they were clearly influenced by their shared experiences of British rule and the political as well as the administrative structures that they had been bequeathed. And crucially, both encountered difficulties, at the state or provincial level, which highlighted the contingency of citizenship in the transition from colonial rule to independent government. But while India inherited most of its political, administrative, judicial and security structures largely intact, Pakistan was required to build a centralized state from the remains of provincial administrative structures, which in the case of the Punjab and Bengal had hurriedly been cut in two. This meant that in Pakistan (by comparison to India) the choices of unitary symbols were dependent on a more unstable – arguably artificial – balance of regional identities and likewise heavily influenced by the political circumstances at the moment of Independence alongside the wielding of the religious card, that is, Islam. In other words, Pakistan did not have as many ‘ready-made’ national histories on which to base the idea of a unitary independent identity as India did, and, as a result, in the words of Christophe Jaffrelot, ‘Pakistan was born of a partition which over-determined its subsequent trajectory’.Footnote 5 The choice to pursue a unitary political system, and the symbols that accompanied this, therefore, had different outcomes for each country.

All the same, official government-driven attempts to propagate civic notions of national belonging could be contested at different scales, within formal institutions and in popular movements in both countries. For Pakistan, this involved, at one level, a tension between local (Punjabi) and migrant (muhajir) cultures that were dominant in the army, administration and politics, against demographically important regional identities, especially in East Bengal but also present in other provinces. In contrast, the idea of the Indian ‘citizen’ was more atomized given that country’s greater size and resultant complexities, but equally, this process turned out to be no less about the consolidation of power around certain majoritarian symbols for the new regime.Footnote 6 For the Indian government, following Independence, it was not as if ideas of the nation had to be invented afresh as in Pakistan. Quite the opposite. The last century of colonial rule in the subcontinent had produced richly documented and highly contentious debates about ‘Indian-ness’ and the ‘Indian people’, from which the notion of ‘Pakistan’ itself had arisen as one dynamic, in terms of political representationFootnote 7 and the politics of identity.Footnote 8 However, when we focus specifically on citizenship, with all that this implied in terms of actual or anticipated constitutional rights, rather than the nation state as a whole, we can see that there were a range of contingent events, on occasion revolving around large-scale ceremonies, which complicated the symbols that each country used to reinforce its new national identity.

After 14/15 August 1947, South Asia’s new postcolonial regimes quickly realized that opportunities had arisen to shape cultures of national identity together with citizenship values by connecting popular political symbols to state power. In India and Pakistan alike, this objective was pursued repeatedly in a series of staged ceremonial occasions, some of them serendipitous and others deliberately planned around the annual calendar marking such values as ‘Independence’ and the ‘Republic’. This chapter accordingly takes as its starting point the impact of two key happenings – the deaths and subsequent funerals of Gandhi and Jinnah in January and September 1948, respectively. It explores their fallout in terms of the ceremonies that they triggered and locates them within the broader assortment of ceremonial processes that took place at a range of regional and political scales during this period, before considering ways in which India and Pakistan projected their authority vis-à-vis their citizens during these nation-building years. In particular, while this chapter’s purview inevitably extends to more general developments as well, it focusses particularly on reactions in two specific places, namely the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh (UP) and the Pakistani province of Sindh, where issues connected with ‘belonging’ lay at the heart of much discussion about the evolving relationship between the postcolonial state and its citizens.

Personifying the Postcolonial State

An early pivotal moment for the new Indian government as far as the special use of symbolic nation-building ceremonies was concerned followed the demise of one of the masters of large-scale mobilization itself. On 30 January 1948, while at a prayer meeting in the gardens of Birla House in New Delhi, Gandhi came face to face with a Hindu extremist, Nathuram Godse, who shot him three times at point-blank range. In a real sense, the response to the murder provided India’s new postcolonial regime with an opportunity to settle some political scores, but it also suggested, in a microcosm, how the use of commonly agreed national symbols could be interpreted and remoulded in multiple quotidian ways. Less than nine months later, with Jinnah’s death from natural causes on 11 September, the new authorities in Karachi faced a similar challenge and reached similar conclusions.

In the weeks preceding Gandhi’s assassination in early 1948, his efforts had shifted from Calcutta to Delhi where more and more Hindu and Sikh refugees were arriving from the Pakistani province of Sindh, ‘with their uncompromising bitterness towards the Muslims’, and Delhi Muslims in large numbers were ‘leaving their homes in the mixed localities of the city and concentrating themselves in those areas where Muslims had a preponderating majority’. Gandhi – in his efforts to restore ‘communal peace’ and ‘keeping in remarkably close touch with Indian opinion’ – campaigned for sufficient reconciliation between communities to allow ‘Muslims to return in safety to their homes in Delhi and non-Muslims to Pakistan’.Footnote 9 When he broke what turned out to be his final fast on 18 January,Footnote 10 it was in response to receiving assurances from all communities in Delhi that Muslim life, property and religion would be both respected and protected. The press also pointed out the effects of the fast in Pakistan as well as among Muslim leaders in India.Footnote 11

But in the first few hours, as the news of Gandhi’s death spread, there was the fear that a Muslim might have been responsible. Violent reprisal attacks against Muslims consequently occurred in Lucknow and Bombay,Footnote 12 and military commanders all over India were told to stand by in case of an emergency in other cities.Footnote 13 Within the space of a few days, once it became known that the attacker was a member of the Hindu right-wing organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), arrests took place, rounding up members of that militaristic organization and declaring it illegal.Footnote 14 This led to mass arrests in Allahabad and Kanpur, and popular attacks on the main RSS offices in the latter city.Footnote 15 Similar arrests were made of Hindu Mahasabha leaders.Footnote 16 The assassination thus provided state governments with an opportunity to maintain public order in response to the ‘volunteer’ organizations that dated from the war years and were still operating. Indeed, this was the context for the passage of the 1948 United Provinces Maintenance of Public Order Bill, which sought to prevent the members of volunteer organizations from wearing any uniform or article of apparel that resembled in any way what was worn by the police or military called out to quell disturbances.Footnote 17 In UP too, to allay public fears, newspapers claimed to be able to provide detailed figures of arrests: in Lucknow it was reported that many of UP’s RSS men had gone underground and that the government had decided to sequester their property. Reported arrests included those in Aligarh (twenty), Allahabad (eight), Bahraich (twenty), Budaun (eight), Ballia (five), Jaunpur, Lakhimpur (fifteen) and Meerut (twenty-five). In Hardoi, anti-Gandhi posters were found, while in Bara Banki the district organizer was charged for assaulting a Congressman and in Fatehpur five RSS members were arrested for distributing sweets in celebration of Gandhi’s death.Footnote 18

In the Constituent Assembly, India’s first Home Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Vallabhai Patel fielded awkward questions about whether government servants could still belong to ‘communal organizations’ such as the RSS. His reply was that they were prohibited from political groups as well as from those ‘which [tended] directly or indirectly to promote feelings of hatred and enmity between different classes or disturb public peace’, although social welfare groups were exempted.Footnote 19 Patel himself, who had been seen as a leader with some sympathies for the Hindu Right of the Congress, also came under fire from a number of sources for apparently not taking sufficient care over the security linked to Gandhi’s final prayer meeting. Overseas reporters closely monitoring these unfolding developments suggested that their repercussions might spread to Pakistan, where there was a danger of them stimulating a ‘communal frenzy’, given preaching by the Hindu Mahasabha and the RSS against Pakistan.Footnote 20

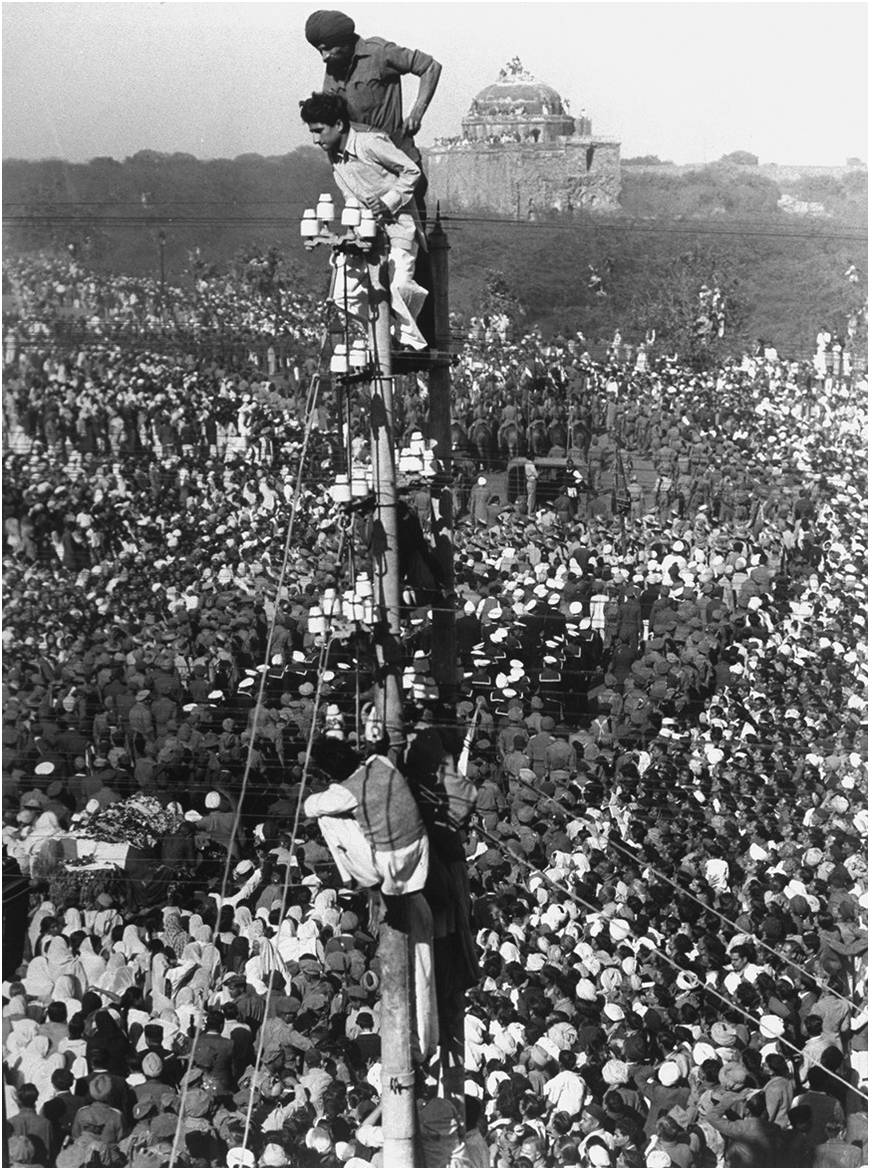

Yasmin Khan has shown how Gandhi’s funeral and the subsequent dispersal of his ashes to different parts of India operated as a key mechanism for the consolidation of Congress power together with the idea of the secular state.Footnote 21 However, in extending Khan’s argument, it is clear that quotidian responses to national symbols could often test these larger ideas on the basis of regional and local readings of India’s past. Certainly, extraordinary scenes of public grief followed Gandhi’s death, with one of UP’s prominent newspapers including only one column on its front page as an expression of national shock and mourning, the day after the assassination.Footnote 22 A large-scale funeral in New Delhi was followed by a two-week official mourning and then the immersion of his ashes in the Ganges. The public reaction involved immense numbers of people, with reportedly more than a million congregating in the city of Allahabad alone (see Figure 1.1).Footnote 23 The political symbolism of this national event conveyed the tragedies of religious conflict (Gandhi had been killed at the hands of a Hindu extremist), and, by extension, the urgency of ‘secularism’ and the triumph of the Congress as its main champion.Footnote 24 This in itself was a powerful symbolic resource for Congress politicians, shortly following Independence, not least because the apparent threat of both the right-wing of the Congress and right-wing parties such as the Hindu Mahasabha was still significant in the lead-up to the first national elections of 1951–2. Hindu traditionalists, including Purushottam Das Tandon who was successfully elected as Congress president in 1950, were in the ascendant as a result of the refugee crisis and the desire by some within the party to assimilate the right-wing RSS outfit (despite its ban following Gandhi’s death) into the Congress Party organization itself.Footnote 25

But it was the forms by which symbols of reconciliation and secularism were scaled both upwards and downwards which marked the extraordinary translatability of these events to a range of public contexts. As we will see later, local responses often challenged or subverted official narratives. Gandhi’s death allowed the new Congress-led regime to consolidate its power – both at local and symbolic levels – in its strategic use of the state apparatus and in the strengthening of Nehru’s executive authority.Footnote 26 The huge official funeral, which passed through the grand colonial spaces of Delhi, was witnessed by crowds lining the malls as its key audience in a specific set of Delhi-based rituals (see Figure 1.2). Khan shows how, in the aftermath of the funeral, there was a clamour for Gandhi’s bodily remains.Footnote 27 Once Gandhi’s pyre was lit on the evening of 31 January, Nehru had to issue orders to save throngs of people (the overall crowd numbered between 700,000 and one million) from falling into the fire.Footnote 28 At the specific location where the Mahatma had died, now considered by many to be a sacred site, people gathered up handfuls of the earth, leaving a large hole in the ground. Raj Ghat later became a memorial park for a range of other leaders – a sacred cremation space on the banks of the Yamuna, which related to Delhi’s complex historical geography.Footnote 29 At the same time, the effect of Gandhi’s passing was experienced in a multitude of other spaces. The UP press made a great deal of the international responses to the assassination.Footnote 30

Figure 1.2 People watching Mohandas K. Gandhi’s funeral, Delhi, 31 January 1948.

It was in the use of Gandhi’s ashes that the spatial underpinnings of the new regime’s secularism were most clearly demonstrated. Ashes were distributed from Delhi to all the states of India where they were scattered in local rivers, linking together the country’s physical and political geography. This well-publicized network extended out from Delhi and, importantly, was under direct Congress control and supervision. It seemed far from coincidental that several of the locations set for receipt of his ashes were areas of religious conflict – for instance, the Punjab in the north-west and Hyderabad (Deccan) in the south.Footnote 31

Ironically, shortly before his death Gandhi had as usual been protesting about matters that linked the local and quotidian to the national.Footnote 32 Undertaking a fast for ‘communal unity’ in the context of the refugee problem in Delhi in early 1948 in response to communal tensions, he had set out the conditions for the breaking of his protest: the annual fair at the dargah (shrine) of the early thirteenth-century Muslim mystic Khawja Bakhtyar (also known as Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki), he argued, should be held, and Muslims ought be able to join it without fear; all mosques which in recent riots in Delhi had been converted into temples or residential accommodation needed to be returned to Muslims to become mosques again; Muslims should be able to move about without fear in formerly Muslim-majority areas of Delhi such as Karolbagh, Sabzimundi and Paharganj; Hindus should not object to the return of Muslims to Delhi; Muslims had the right to travel in railway trains without any risks; there should be no economic boycott of Muslims and the accommodation of non-Muslims in Muslim areas ought be left entirely to the discretion of the residents of those areas.Footnote 33

As on many previous occasions, just before his murder Gandhi had successfully created publicity around a controversy that connected to high-level political struggles within the Congress Party and which had repercussions through India’s entire polity. Official reports on Gandhi’s motivation for fasting in early 1948, as related to India’s Governor General Mountbatten, set out the former’s annoyance at the policy of Patel towards Delhi’s Muslims.Footnote 34 The external – British – interpretation was that the fast was as much designed to bring reconciliation between the two leaders as it was about the city’s Muslim inhabitants,Footnote 35 and the controversy was even accompanied by positive reflections on Gandhi’s motives in the Pakistani press.Footnote 36 Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the leading Congress Muslim politician, also described how Patel remained ‘indifferent’ to the fasting, believing that these actions were directed at him, and as a result – Azad claimed – this affected local security arrangements for Gandhi in Delhi. Patel’s apparent lack of concern came back to haunt him following the Mahatma’s death. Gandhian politicians such as Jayaprakash Narayan and Prafulla Chandra Ghosh both held Patel publicly responsible for the lack of protection. Consequently, Gandhi’s protests concerning the treatment of Muslims in India, together with his subsequent assassination, had a range of disciplinary repercussions for the Congress Party, and individual figures associated with it. There were knock-on consequences that filtered down to local Congress committees and to low-level administrators. Police, for instance, investigated those allegedly holding public meetings to celebrate Gandhi’s death, with such events taking place in Gwalior and Jaipur where sweets were distributed;Footnote 37 and two kanungos (local revenue officers) in Ghaziabad district, B. K. Mathur Tahsildar and Anand Swarup, faced punishments for various misdemeanours, including the claim that they ‘indulged in drinking wine on the night of Gandhiji’s assassination’.Footnote 38

Perhaps the most important quotidian significance of Gandhi’s death was the range of implications that it had, on the one hand, for spontaneous popular protests around communal organizations and, on the other, for generating opportunities for local policemen and administrators to settle old as well as new scores. Exploring the spontaneous reactions that took place, we gain a sense of how ordinary citizens in urban UP and beyond identified with the larger symbols of national belonging. The news of Gandhi’s death created shock across the city of Banaras, and both Hindu and Muslim shops simultaneously closed. All public employees took a day off.Footnote 39 Importantly, a similar spontaneous closure of shops also took place in Karachi, Sindh.Footnote 40 More directly, there was an attack by a large mob on the house of Veer Savarkar (Hindu Mahasabha leader) in the Dadar Mahim area of Bombay,Footnote 41 and a student demonstration in Lucknow in support of Gandhi and against the various organizations deemed responsible for his demise.Footnote 42 There were also local-level clampdowns on the Muslim National Guard and Khaksars, including community leaders who had held, for instance, the Chairmanship of the Bahraich Board.Footnote 43 In other centres in UP, opportunities were presented for assimilating RSS cadres into the Congress, with speakers at a meeting held by the president of the Lucknow Congress Committee suggesting that all (banned) RSS members should be absorbed into the Congress Seva Dal in each mohalla (urban neighbourhood).Footnote 44

Clearly, as these instances collectively testify, the political moment created by Gandhi’s assassination, alongside the very public ceremony of his funeral generated by the regime itself, allowed for new and spontaneous material interactions between citizens and the political process. In a very real sense, and in a way quite different to mass mobilizations in the colonial era, people involved in street politics were now able to engage directly with the political theories of Gandhism and Nehruvian secularism. In addition, the anticipation of fresh political freedoms, and the now poignant ‘example’ of Gandhi, had brought a heightened sense of how new governments were expected to operate: how, in particular, there was an acknowledged need to move away from the old bureaucratic approaches of British India.Footnote 45 Decolonization, in short, cultivated new public expectations that postcolonial regimes sought to channel and control, but which were exposed very clearly in such times of collective uncertainty.

Gandhi could not have died at a better time for the new regime under Nehru’s leadership, for three significant reasons. First, developments just before his death represented a means for potentially bolstering the secular ideology of Nehru, something that he could use to confront the position of his rival, the more religiously conservative Patel. This would prove to be significant in the context of a renewed social and political conservatism evident in Indian Constituent Assembly debates of 1948–9 concerning refugees, women’s rehabilitation and the hard line that was being urged in relation to Pakistan. Second, the specific timing of Gandhi’s death, shortly after the already-fixed ‘Independence Day’ of 26 January (later to become ‘Republic Day’) that two years afterwards would be the date on which the Constitution was inaugurated, brought together two key memorial events. These directly served a politics of reconciliation and the idea of the rootedness of the Congress organization in the rights of the Constitution itself. Finally, while few were embarrassed to evoke Gandhi while he was alive, his death and accompanying ‘loss’ to India – at least for a time – provided another public opportunity to celebrate Gandhian values. This readiness was strongly reflected in contemporary press editorials. As The Hindu declared on 31 January 1948,

… let us face, as the Prime Minister exhorts us to do, all the perils that encompass us – and they are many and grave … If we are true to Gandhiji’s teachings, nothing must deflect us from considering all classes, castes and communities as children of the same mother, entitled to equal rights and – what is not less important – charged with equal responsibilities, all acting in harmony, earnestness and unison in the interest of the nation as a whole.Footnote 46

But beyond local politics and street demonstrations, the force of Gandhi’s murder lay in the effect it had on political debate and media commentaries. Gandhian ideas, especially given the violent and precipitate nature of his death, were represented as both universal and eternal in a range of forums. Many reflected on his calls for political morality, such as their use by a pamphleteer, Amar Nath Shastri, writing to Nehru in 1948 about Gandhi’s passing as an explanation for state corruption, together with the need for his memory to keep things ‘clean’.Footnote 47 Others complained about political selections to constituencies, either against those who had made celebratory speeches when Gandhi had died,Footnote 48 or in favour of those who claimed to have planned events in celebration.Footnote 49 Gandhian ideas affected forms of public morality in other ways: in Bombay in 1950, the local government refused to certify a cigarette advertising film entitled Ek Kash Ki Kahani (A Story of a Puff) for Cavender’s Cigarettes. The film, censors argued, associated the father of the nation with its propaganda to encourage smoking, especially as it contained sequences with Gandhi’s photograph, smokers in a cloth shop and ‘the anger of a mother-in-law’ dispelled by the aroma of cigarette smoke.Footnote 50

Hence, the timing of Gandhi’s death was a gift that could keep giving for the Congress. Its anniversary each year neatly coincided with annual Republic Days, allowing and encouraging public engagement to meld the memory of this with a particular ‘reading’ of the Indian Constitution itself. At an address at a public meeting on Sarvodaya Day at the Ramlila Grounds, New Delhi, on 30 January 1950, Nehru’s speech about the Republic suggested to the audience that ‘perhaps you may already be aware of your rights – little more clearly than is necessary – but it is equally necessary to know your responsibilities, otherwise a nation cannot function’. Nehru deliberately phrased his call in terms of Gandhian notions of how unjust laws could be changed via a consensus between the will of the government and the will of the people,Footnote 51 something that required not just the legal implementation of the Constitution but its active connection to civic responsibilities.Footnote 52 Such connections allowed the leadership to safely re-enact popular struggles with autocracy, which (via reference to Gandhi) stood aside and above global materialism. Crucially, too, they affected Nehru’s own projected policy towards Pakistan, which served a dual purpose of relative reconciliation on the international stage, together with internal control of the Congress right wing: by speaking of the ‘panic and fear’ of the Pakistani press, Nehru emphasized the need for India not to resort to ‘panic and fear’ in relation to Pakistan.Footnote 53

Across the border, like Gandhi’s funeral, that of Jinnah held later the same year in Pakistan’s federal capital city of Karachi represented an early ‘ceremonial’ opportunity for the embryonic Pakistani state to project itself (see Figure 1.3). News of Jinnah’s death on 11 September 1948 stunned Pakistan’s new citizens. Although he did not die unexpectedly like Gandhi at the hands of an assassin, Jinnah had been growing steadily more unwell for some time – he had suffered from tuberculosis since the 1930s and then developed lung cancer. But awareness of Jinnah’s declining health had been kept a closely guarded secret, and so his passing took most Pakistanis by surprise. Nor was this collective grief helped by the revelation that the ambulance transporting him from Karachi airport to his official residence had broken down en route, forcing him to wait at the side of the road for an hour before a replacement vehicle arrived. Jinnah’s body was placed on public view at Government House where thousands visited to pay their respects. The enormous number of assembled mourners – a reported million people gathered in the city – who lined the three-mile-long funeral route the following day was credited with behaving in the main with admirable discipline, though, as one British High Commission report noted, ‘the vast crowds who swarmed around the bier … at one point completely disorganized the official programme’.Footnote 54 In an interesting and perhaps telling inversion of what had happened in India, British Pathé newsreel, which filmed the sea of people attending Jinnah’s funeral, showed mourners scattering soil that had apparently been brought from ‘all over the new nation’ on his grave. In contrast to the nationwide distribution of Gandhi’s ashes mentioned above, this ceremony materially and metaphorically sought to connect in symbolic fashion the country’s constituent parts with its newly created political centre in Karachi.Footnote 55 Whereas the Congress had quickly realized the necessity to extend its authority outwards to other states in the lead-up to the first general elections in India, in Pakistan the problem was still one of the need or desire to centralize.

Figure 1.3 A view of M. A. Jinnah’s funeral, Karachi, 12 September 1948.

The Indian High Commissioner who attended Jinnah’s funeral along with other members of the diplomat corps present in Karachi described events in detail to the authorities back in Delhi:

[Members of the diplomatic corps] turned up in full force, most of them in full morning dress with toppers. Jinnah lay on a low bed covered with a white sheet with a few rose petals strewn thereon. His face was bare, eyes closed and mouth open. I learn now that this was because he wore false teeth which according to Muslim custom are not buried with the body. The face showed acute and prolonged suffering, was horribly emaciated and shrivelled, and it looked as if the man had been dead a long while and not only the night before as given out. Zafrullah [Khan, Pakistan’s Foreign Minister] was very composed. I thought I detected even a faint smile flickering about his lips. He was the first to shoulder the bier. The procession itself numbered over a lakh [100,000] and was most orderly. Everyone was on foot. There were no women except Fatima Jinnah, Jinnah’s daughter Mrs. Wadia, Lady Hidayatullah [wife of the Governor of Sindh] and Mrs. Tyabji, wife of the Chief Judge of the Sind Court.Footnote 56

With government offices closed for three days, private businesses were not legally obliged to shut, but most chose to do so, though the spontaneity of shared grief was marred by the presence of roving bands of ‘self-appointed enforcers’ who reportedly caused unpleasant scenes, including setting fire to one of Karachi’s principal restaurants.Footnote 57 On 22 October, the final act in Jinnah’s mourning ceremonies (chelum) took place when a crowd estimated by observers at around 400,000 assembled near his burial place to pray and to listen to tributes from the country’s top leaders.Footnote 58 The main focus of the speech by the new Governor General Khwaja Nazimuddin was the need for ‘faith, unity and discipline if Jinnah’s creation – Pakistan – was to reach fruition’: ‘the people’, he advised, ought to ‘scrupulously refrain from raising issues likely to create disruption or weaken authority and it was everyone’s duty to join [the] armed forces and to subscribe to defence loans’.Footnote 59 On the occasion of Eid ul Azha, as part of the Hajj ceremonies, a few weeks later, Nazimuddin called on Pakistanis to dedicate themselves to ‘the task nearest to the Quaid-i-Azam’s heart – the establishment of a model Islamic state in Pakistan, a task requiring untiring effort, devotion to duty and a spirit of sacrifice’,Footnote 60 and ‘thousands [were said to have already made] pilgrimage to Quaid’s grave’.Footnote 61 The reports by the Indian High Commission in Karachi, though they acknowledged that ‘Jinnah’s grave [had] become a place of pilgrimage for Muslims far and near’, disputed the number of people visiting it on a daily basis. Rather, as Indian officials explained, enthusiasm was being ‘kept alive by occasional free bus rides to the grave side, [and] by photographers being arranged to be in attendance when any one of importance visits the grave side to lay a wreath’. These photographs were then duly published in newspapers such as Dawn, giving visitors ‘the satisfaction of not only seeing themselves … but also offering proof of their loyalty to the State’.Footnote 62

What the Indian High Commission, however, could confirm was the speed with which the land around the grave was cleared and levelled as part of the Pakistan government’s plan to build a ‘mosque, a replica of the Jumma Masjid in Delhi, an exquisite mausoleum over Jinnah’s grave, a Dar-ul-Ulum [religious seminary] and an institute of technology’ on the site. But while these schemes were given top priority, apparently placing other plans to build a new site for the federal headquarters in the vicinity of Karachi and a diplomatic colony into “‘cold storage’, the initial response from the public in terms of donating funds was described as disappointing:

[Syed Hashim] Raza, Administrator of Karachi called a public meeting in which the non-Muslims outnumbered the Muslims and the Parsis outnumbered the non-Muslims. It was given out that an announcement would be made as soon as Rs 10 lakhs had been collected. [But] as no announcement has so far been made, it may be presumed that even this paltry sum is not yet forthcoming.Footnote 63

All the same, for local politicians, foreign dignitaries and ordinary citizens, the act of visiting the final resting place of the country’s ‘founding father’ acquired enormous symbolic importance, with official and military ceremonies taking place there on special occasions. The first official act of the newly installed bishop of Karachi, for instance, was to visit Jinnah’s grave in October 1948 to offer prayers and blessings.Footnote 64 As one visitor in 1950 commented in his private diary, there was a ‘huge crowd there all the time, particularly on Thursday. His grave has become a place of pilgrimage. I saw a few people reading the Quran. They have turned it into a saint’s shrine. At one stage there was even qawwali. But the Government of Pakistan has banned that’.Footnote 65

In August 1949, with the first anniversary of Jinnah’s death fast approaching, the authorities had to decide how the occasion was to be marked. People were requested ‘to pay homage to the Father of the Nation and the Founder of the State’ by participating in the largest possible number at a fateha khawani (condolence prayer meeting) to be held at his tomb and ‘to bring with them their own copy of the Holy Quran for recitation’. A public meeting was also scheduled for the evening, to be addressed by Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman, chairman of the Muslim League, and other prominent personalities.Footnote 66 While the Quaid-i-Azam Relief Fund, set up to coordinate the various provincial, central and private refugee relief agencies, was intended to provide a lasting legacy of a more practical kind, the Pakistani authorities like their Indian counterparts took pains to prohibit any unauthorized use of Jinnah’s name. As reports in the intensely patriotic Karachi newspaper Dawn explained in 1949, ‘it [had] been observed that the hallowed name of the Quaid is being exploited by petty shopkeepers in Karachi. This tendency is objectionable unless official permission is obtained and all those shops who are using the Quaid-i-Azam’s name without official permission are given time to stop doing so by the 1st of May 1949’.Footnote 67 This prohibition proved ineffective, however. Just a few months later, there were still reports of Jinnah’s face appearing in advertisements for ‘Pak’ and ‘Badshahi’ bidis (cigarettes),Footnote 68 while in 1950, a disgruntled Karachi resident complained that

Although the Government have prohibited the use, association and display of Quaid-i-Azam’s name and photo for purposes of business, advertisements etc., it is regretted that in actual practice these instructions are deliberately violated. Sometime ago I happened to see an advertisement in the city about Quaid-i-Azam Brand Pure Ghee. A medicine ‘Jinnahspirin’ is being openly sold. In certain cinema houses it has become a practice to display Quaid-i-Azam in pencil and chalk drawing with incorrect spelling of the leader’s name. It is time that the authorities took serious view of such practices and punish the offenders. We must show due respect to the founder of our State and even if his photo is to be displayed on the screen it must be one which is officially accepted by the Government.Footnote 69

The same point was picked up by newspaper editors who reflected on the broader misuse of ‘great names’, citing with admiration Gandhi’s opposition to cigarettes being named after him: as a Dawn editorial commented,

There has been an increasing tendency … to name business concerns after Quaid-i-Azam. We can quite see that those who do it do so in order to seek blessing in their own way, from that great name, and thereby to make their wares attractive or acceptable to the customer. … It is for the leaders and the Press of this country to explain this legislation [forbidding misuse of Jinnah’s name] to the common people. There is much in a name: a great name has to be lived up to and not to be traded upon.Footnote 70

In October 1951, following his own assassination, the body of Pakistan’s first Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan was brought to Karachi from Rawalpindi and buried close to that of Jinnah, his funeral creating a second occasion for very public shared grieving on a massive scale:

thousands lined the streets of [the] capital to see his body brought from the airport. During the morning it lay on the veranda of his home in a casket heaped high with flowers. Mourners trudged slowly passed it. [In the] afternoon, 250,000 gathered in the polo fields where the coffin was brought for a state display before its burial. There it was laid on a gun carriage decked with flowers and drawn by Pakistan navy men thru [sic] the streets to the burial place.Footnote 71

While this outpouring of national grief was more restrained than when Jinnah had died, the ceremonies associated with Liaquat’s burial in the days and weeks that followed re-focussed the collective attention of the country’s citizens on a site that had already become the emblematic centre of Pakistani national sentiment, and hence the symbolic terrain on which the state both performed and represented its new identity.Footnote 72

Meanwhile in India, political advantages for the new regime continued to be drawn directly from Gandhi’s death anniversaries. This was particularly evident in the period leading up to India’s first general elections in 1951–2 with supporters of the prime minister calling for Nehru to be seen as Gandhi’s ‘heir’. As we will explore in more detail in later chapters, Nehru derived considerable political mileage from this association when he confronted Tandon over the presidency of the Congress Party in 1951. As one national Indian newspaper put it, following the resignation of Tandon, the more ‘secular’ and ‘Gandhian’ leadership of Nehru suited him for this position: ‘Congress opinion is agreed that today’s decision of the AICC [All-India Congress Committee] to entrust Mr Nehru with full-fledged leadership of the Congress would have a tonic effect on Muslims and other minorities. It is also held possible that Muslims would join the Congress more readily and in larger numbers than under the presidentship of Mr. Tandon’.Footnote 73 However, once the Congress had firmly established itself following its successes in the first general elections, these kinds of references to Gandhi’s legacy grew less frequent. Instead, at least in localities like UP, discussion revolved around a new generation of largely career politicians who no longer felt the need to pay the same degree of ideological lip service to the Mahatma.Footnote 74 Similarly, by the mid-1950s, commemorations for Jinnah in Pakistan had become more routine, with instructions in 1955 – the seventh anniversary of Jinnah’s death – stating that a condolence prayer meeting (fateha khawani) would be held both at his mazar (tomb) and at the residence of his sister, Fatima Jinnah. But provincial governments were given strict orders that while they should put suitable arrangements in place, no public meetings were to be held ‘under official auspice [sic], nor flags … flown at half-mast’.Footnote 75

Projecting the New State

When Pakistan and India came into existence on midnight on 14/15 August 1947, as was the case in many other states making the transition from colonial rule, their political leaders faced enormous mutual challenges as far as turning what had been a demand for political rights into a reality. In India, the transition to Independence ought to be viewed as a medium to long-term process, not least because notions of autonomy can be traced at least back to the framework under which Congress governments had held power in eight of British India’s eleven provinces between 1937 and 1939. The period from the end of the Second World War, and especially following the elections of the winter of 1945–6, also signalled that the end of colonial rule was in sight. Yet while Partition refugees proved to be a consistent focus of public attention after August 1947, there was surprisingly little reflection in UP newspapers on the possible changes to the lives of most Indians that might have been brought about by these dramatic events in terms of new or anticipated democratic rights. Instead, when reflections on the meanings of ‘Independence’ did take place, they tended to be explored through the more murky lens of everyday problems – food supply, political problems, corruption and shortages. On the Pakistani side of the border, circumstances were by their nature more precipitate but also shaped by local considerations. For all the enthusiasm of those who at the stroke of midnight had found themselves ‘Pakistanis’, the reality of their new state meant very little to most people now living within its newly drawn-up frontiers. Despite the public celebrations that took place in Karachi to signal the official British handover, it was said that the vast majority of its new citizens ‘scarcely realised that Pakistan had really come about’.Footnote 76 ‘Pakistan’ had after all been a rallying cry, envisaged – towards the later stages of the struggle to end British rule – first and foremost as a place that was not ‘India’. Jinnah, when he had inaugurated Pakistan’s separate Constituent Assembly on 11 August, referred to the creation of Pakistan as a ‘supreme moment’, and ‘the fulfilment of the destiny of the Muslim nation’. But as contemporaries astutely recalled, while Independence celebrations were ‘carried off with very scanty means and not in as perfect a manner as at Delhi … that never struck one as incongruous as it was improvised, Pakistan itself was being improvised’.Footnote 77

Almost overnight, anything and everything that could be was re-labelled as ‘Pakistan’ or ‘Pakistani’: for many people there, just to hear the name of their country reportedly became a ‘source of pride’.Footnote 78 From ministries to refugee rehabilitation boards to the railway, ‘Pakistan’ was added to their official designation. In due course, firms were advised to brand their products ‘Made in Pakistan’, so as to encourage ‘patriotic’ Pakistanis not to confuse them with foreign (Indian?) manufactures. And, day in and day out, the instruction to ‘Patronise Pakistani Products’ reverberated from public platforms and government speeches.Footnote 79 Acts as mundane as posting a letter turned into a way of projecting the same message. From October 1947, this required the use of former British India stamps overprinted with the word ‘Pakistan’, and franked with the slogan ‘Pakistan zindabad’ (Long Live Pakistan). It was not until July 1948 that the Pakistani authorities issued the country’s first set of postal stamps. Produced to celebrate the first anniversary of Independence,Footnote 80 none of the four stamps, however, contained images that were directly connected with the eastern – Bengali – wing of the country: instead three depicted buildings in West PakistanFootnote 81 while the fourth (apparently approved by Jinnah himself) was based on the crescent and star motif made familiar by the League’s own flag, itself the template for Pakistan’s national emblem (see Figure 1.4).Footnote 82

India’s own postal stamps showed an equal level of concern about territory and borders, especially vis-à-vis Pakistan. India’s territorial claim to Kashmir was included on the 1950s’ stamps depicting the map of India, where the whole province was included in cartographic representations, including the part beyond the 1948 ceasefire line.Footnote 83 India was less careful in the representation of its north-eastern boundaries, where, despite in effect ‘annexing’ Bhutan on maps from this time, it was suggested that 31,000 square miles of territory disputed with China lay ‘outside’ India. But Portuguese India, not absorbed within the Union until 1961, was incorporated in the maps of India on postage stamps in the 1950s.Footnote 84

As far as currency was concerned, Pakistanis initially carried on using British India bank notes and coins until April 1948, when the Reserve Bank of India issued currency for use exclusively within Pakistan (that is, without the possibility of redemption in India). Still printed by the India Security Press in Nasik (in what was then the Indian state of Bombay), the new banknotes were produced from Indian plates now engraved (rather than overprinted) with ‘GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN’ in English and its Urdu translation Hukumat-i-Pakistan added at the top and bottom on the front only (see Figure 1.5).Footnote 85 This move, however, unsurprisingly created considerable confusion at first, and so official statements were needed to clarify that while the new bank notes were legal tender only in Pakistan, Government of India notes would continue to circulate for the foreseeable future.Footnote 86 Moreover, Pakistani and Indian rupees remained interchangeable up to 1949, when the two currencies finally went their separate ways after India but not Pakistan devalued its rupee and introduced new currency notes,Footnote 87 a move that contemporaries regarded as an opportunity for the country to pursue its own best interests regarding its currency status even if, in the short term, the shortage of Pakistani coins in circulation created local difficulties.Footnote 88

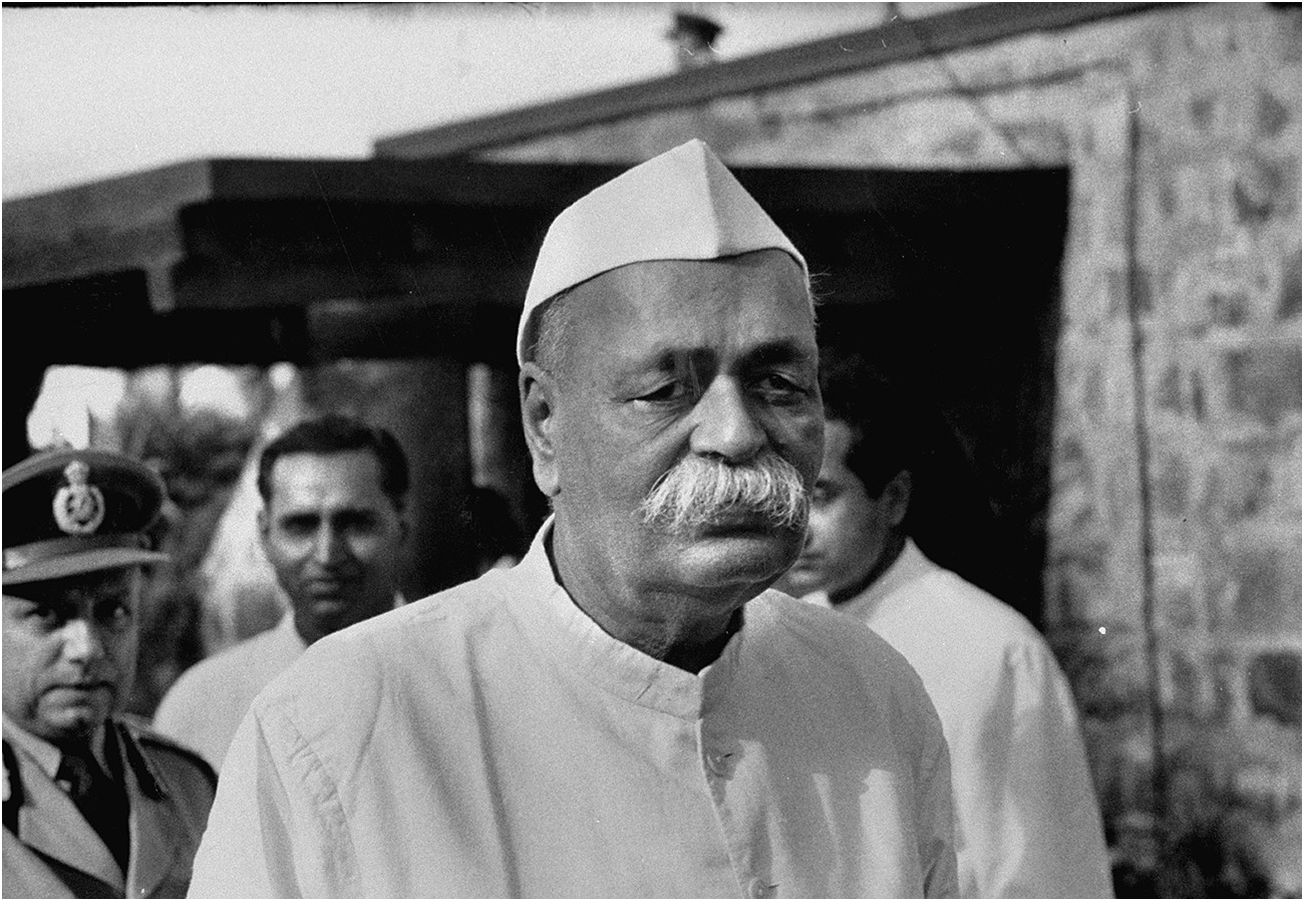

One of the interesting inversions for India following Independence, and a topic that generated much media comment, was the role of administrative officers and policemen who had served the colonial regime and their ‘transition’ to a new democratic context. This changeover was critically important for all citizens given the fact that not only was the local bureaucrat or police officer the tangible face of the new ‘state’ but also one that had become especially palpable in the light of food and civil supply problems through the war years and thereafter. In early January 1948, the UP Governor Sarojini Naidu declared at the annual police parade at Lucknow that those who had fought for the freedom of the country were no longer simply ‘badmashes’ (criminals) but rather badmashes ‘in service of the country’, whose duty was now to ‘work as protectors of the people’.Footnote 89 There were plenty of general articles on the new spirit of service that ought to imbue the public servants’ relations to the people.Footnote 90 In similar fashion, just over a week later, G. B. Pant, chief minister of the state (see Figure 1.6), addressed a conference of policemen in the city of Kanpur. In his speech he declared that ‘The days when we detested the red turbans are over’. Pant proceeded to highlight the urgent need to fight bribery and corruption, instructing policemen to behave towards the people in the way that they would expect their fellow officers to behave with their own kinsmen elsewhere in the country: as he reminded them, ‘Today, you are not merely policemen, but citizens of a free nation’.Footnote 91

Figure 1.6 Govind Ballabh Pant, first premier/chief minister of UP.

Nevertheless, there were plenty of instances, in UP at least, when complaints swiftly arose about the ‘failed’ administration of newly democratic India, which in the eyes of its critics had not fully made the transition away from colonial governance. For instance, in the ‘Reader’s Forum’ of Lucknow’s National Herald newspaper, one G. Misra commented that the ‘dawn of freedom’ had been accompanied by a new menace in the district of Gorakhpur in the eastern part of UP – namely, the interaction between official and non-official. Misra gave the case of a particular magistrate, who was allegedly ‘holding jurisdiction in many different areas’ beyond his formal powers. ‘These power hungry administrators’, Misra concluded, ‘are doing things which discredit the people’s government and the Congress’.Footnote 92 As we will see in later chapters, the ‘reconstruction’ of the state administration to accommodate, in particular, the new demands of welfare, local government, land redistribution (zamindari abolition) and supply of goods often stimulated public debate about the role of minorities, migrants and refugees as far as public employment was concerned.

Unlike independent India that inherited the former headquarters of colonial power – New Delhi – together with a range of ready-made ‘national’ institutions already in place, the politicians and bureaucrats now running Pakistan faced the challenge of creating a whole set of new administrative structures. On the one hand, this infrastructure itself had to embody the ‘state’; on the other hand, it was through this framework that the ‘state’ would have to operate, perform and reproduce itself on a day-to-day basis. At the federal level, a raft of replacement national institutions – ministries, commissions, committees – needed to be put in place, and quickly. Comparable trials and tribulations in terms of reconfiguring everyday administrative structures applied at the provincial level as well. Pakistan’s biggest provinces (in terms of population) – East Bengal and West Punjab – had been parts of two larger units, namely united Bengal and the Punjab, themselves now divided in two. Hence, here too the local administration required extensive re-building. In the case of Sindh, though territorially unaffected by Partition, a large proportion of the province’s non-Muslim government officials left for India in the months following Independence. And as was the case with India, the place of Princely States and tribal areas had yet to be resolved. It was much the same for municipalities and district boards, with their day-to-day operations disrupted by migration and displacement. Other explicitly ‘national’ bodies to be set up included a State Bank – regarded by the press as a necessary symbol of statehood – opened in Karachi on 1 July 1948 by Jinnah, who took the opportunity to call Pakistan’s banking arrangements to be separated from those of India and also to conduct its banking in accordance with so-called Islamic ideals.Footnote 93 Meanwhile, against the backdrop of growing tension with India over Kashmir in 1948, the authorities established a Pakistan National Guard with the ambitious objective of training two million civilians, comprising both women and men, in the use of arms.Footnote 94

In most of India, and particularly in locations such as UP, the Indian state was very closely associated with the principal vehicle of anti-colonial protest, namely the Congress that following Independence transformed itself from an all-embracing national movement into a political party. This association was, at one level, a by-product of colonial power itself: law and order and revenue collection as the principal logics of the colonial system were presided over and controlled by political administrators,Footnote 95 and at least in terms of party organization the Congress necessarily mapped onto much of the same jurisdiction as had existed in the bureaucratic apparatus in the interwar period. Perhaps it was not so strange that power exercised locally involved a bureaucratic-political nexus in which Congress leaders exercised significant authority over local administrators. In effect, the Congress Party equalled the ‘state’ in the eyes of much of the population.Footnote 96 By way of parallel processes in Pakistan, there were complications generated by the fact that the state there, at least in period immediately following Independence, tended to be closely identified with another dominant political party, the Muslim League. To all intents and purposes, state and party were regarded by many Pakistanis (whether they liked it or not) as synonymous, and distinctions between the two extremely were blurred: in the words of Tai Yong Tan and Gyanesh Kudaisya, the League ‘was expected to play a role similar to that of the Indian National Congress in India by providing the leadership and the organizational machinery to ensure and facilitate mass participation in the political structure’.Footnote 97 League politicians automatically assumed key roles both at the centre and in the provinces, dominating the federal Cabinet in Karachi, as well as providing a majority of the members of the Constituent Assembly also located in that city. Ministers and party officials combined their efforts to reinvigorate the League and engender ‘solidarity and discipline in its ranks’.Footnote 98

Under these circumstances, it was often hard in practice, whether in India or in Pakistan, to separate the state in terms of its administrative functions from those interests who claimed to represent it politically. We see this happening in UP, even though government servant rules were set up with the apparent aim of ensuring ‘complete political neutrality’ for government servants.Footnote 99 As we will explore in later chapters, public scandal frequently revolved around the misuse of political patronage towards civil servants and police officers, and the use of bureaucratic transfer. In Pakistan, corresponding patterns were evident, even after a ban on ministers holding party offices was included in the Constitution of the All-Pakistan Muslim League at the time of its formal establishment in February 1948.Footnote 100 Attempts to distinguish between the two were made trickier still by the fact that these same politicians often framed their rhetoric as if they were talking on behalf of the state, rather than the party to which they belonged. Leading Muslim Leaguer and ‘Father of the Nation’ – Jinnah – was transformed overnight into the state’s supreme representative when he assumed the responsibilities of governor general at Independence, and then proceeded to juggle these duties alongside those of the head of the government, leader of the Muslim League and the office of president of the Constituent Assembly.

This high-level process of projecting the independent state often hinged on controlling information flows between India and Pakistan, whose relationship was poor from the start. In January 1948, the UP government issued a notification under the Maintenance of Public Order (Temporary) Act forbidding newspapers there from publishing any news item taken directly from Radio Pakistan in so far as these related to Kashmir, political matters or armed conflict.Footnote 101 To a great extent though, Radio Pakistan’s reach was still very limited, prompting Pakistani politicians at federal and provincial level repeatedly to tour the country in person, in attempts to project the authority of the new state that they now represented as well as their own political interests. In April 1948, for instance, Jinnah – not long after his controversial visit to East Bengal where he drew criticism for his support for Urdu as the country’s sole national language despite a majority of its citizens speaking Bengali – undertook a ‘full and energetic’ tour of the NWFP. There his speeches sought to hammer home the message that the ‘anti-government’ attitude that had so recently helped to remove a foreign (colonial) administration now needed to be replaced by discipline and a constructive approach towards solving Pakistan’s social and economic problems.Footnote 102 Unity and discipline, he emphasized, were required ‘if the difficult task of building Pakistan into [a] solid state was to succeed’. At a joint tribal jirga held against the backdrop of growing tension with India over disputed Kashmir, Jinnah assured assembled Pashtun chiefs that Pakistan, while not wishing to interfere with the internal freedom of their so-called tribes, would provide all possible assistance in educational, social and economic development: in return, he asked for tribal loyalty and assistance in national defence. The local press headlined the tour as a triumphal success, but other contemporaries reported a ‘general sense of disappointment, in part thanks to excessive security restrictions and [also] partly to Jinnah’s failure to appeal to rugged Pathan humour – he … usually spoke in English and kept at a distance from crowds’.Footnote 103

Tours and ceremonial occasions shaped by various party political agenda took place at a local (state or provincial) level too. This has been explored at the level of high state ceremony in UP’s main Congress-led projections of the nation, around flags, Independence Day and the politics of historical reconstruction and renaming.Footnote 104 However, the translation of some of these ideas at local-level perceptions of state power moved beyond the significance of region itself. In the UP city of Allahabad in January 1948, Acharya Jugal Kishore championed the Congress-linked volunteer movement, the Seva Dal, as an organization dedicated to service, self-sacrifice, simplicity, the promotion of national unity and improving the fitness and health of the Indian people through physical culture and training. In times of emergency, the idea was that the Seva Dal would act as a peace and relief brigade, as well as a ‘School of Citizenship’.Footnote 105 In the Tehri district in the north-west of UP, a public meeting was held on 17 January 1948 to commemorate what local politicians described as ‘Deliverance Day’. This anniversary marked the local taking over of law and order by the UP state government and was coordinated by a political-administrative combination of the veteran Indian Civil Service man B. D. Sanwal and Mahabir Tyagi, Congress politician and member of the UP Legislative Assembly for Dehradun. At the gathering in front of Tehri Jail, Tyagi made a speech saying that the officers of the UP government had come to ‘serve the people who were now free’. The provincial government, he reported, had announced compensation to political sufferers, the refund of collective fines imposed on the people of the region, the release of political prisoners and freedom of speech and the press.Footnote 106

In the Pakistani province of Sindh, in March 1948, equivalent grandstanding events were planned and delivered. The president of the Sindh Provincial Muslim League Yusuf Haroon, accompanied by Manzar Alam, the president of the States Muslim League who had migrated to the province from India, undertook the first visit since Independence by League office holders to some of Lower Sindh’s smaller urban centres, including Thatta, Hyderabad and Tando Allahyar. Their official aim was to ‘create an awakening among the masses for the reorganization of the Pakistan Muslim League on a representative basis’, but the majority of Haroon’s time was taken up with addressing complaints about shortages of necessary goods and accusations of corruption in the administration. Even shrouds were apparently difficult to obtain, triggering the suggestion that the authorities should at least provide cloth for the dead even if they could not do so for the living. As one newspaper correspondent asked, ‘Where is the utopia you promised us after the establishment of Pakistan? We have won our independence but can you honestly say that this has made any difference [to] the lot of the common man?’Footnote 107

For many Pakistanis, Jinnah more than anyone or anything else – as reactions to his death discussed above have suggested – symbolized the new state: his rhetoric along with his physical being were both constitutive and representative of Pakistani identity, and hence Pakistan itself. Indeed, Jinnah’s way with words equipped those running the new state with a rich repository of useful nation- and state-building resources. By the early 1950s, the authorities had launched an official Pakistani emblem that featured Jinnah’s most famous saying. Green in colour, and incorporating a crescent and a star, this symbolic shorthand for the state signified Pakistan’s ideological foundation – Islam – while its shield, divided into quarters and showing the country’s major crops at this time – cotton, wheat, tea and jute – pointed to the agricultural base of its economy. The surrounding floral wreath, which alluded to traditional Mughal art forms, emphasized Pakistan’s Indo-Muslim cultural heritage. Finally, the scroll supporting the shield contained three Urdu words – ![]() – that read (from right to left) ‘iman-ittihad-nazm’. Translated as ‘Faith, Unity, Discipline’ – virtues invoked by Jinnah both before and after Independence – these were turned into Pakistan’s official guiding principles, which, emblazoned on hillsides and public monuments, came to acquire pride of place alongside Jinnah’s own portrait as a physical embodiment of Pakistan’s identity and political reality. While their exact ordering has triggered an ongoing debate, in practice, Jinnah himself prioritized them differently in different speeches. In 1950, a letter writer in Dawn suggested that, echoing the Statue of Liberty in New York, ‘the Pakistan Government should construct in memory of our beloved Quaid-i-Azam, a huge structure on the Oyster Rocks in Karachi harbour, just off Clifton, visible miles away to the incoming ships and the planes as well. If possible the words “Unity, Faith and Discipline” may be inscribed on it, and brilliantly lighted at night’.Footnote 108

– that read (from right to left) ‘iman-ittihad-nazm’. Translated as ‘Faith, Unity, Discipline’ – virtues invoked by Jinnah both before and after Independence – these were turned into Pakistan’s official guiding principles, which, emblazoned on hillsides and public monuments, came to acquire pride of place alongside Jinnah’s own portrait as a physical embodiment of Pakistan’s identity and political reality. While their exact ordering has triggered an ongoing debate, in practice, Jinnah himself prioritized them differently in different speeches. In 1950, a letter writer in Dawn suggested that, echoing the Statue of Liberty in New York, ‘the Pakistan Government should construct in memory of our beloved Quaid-i-Azam, a huge structure on the Oyster Rocks in Karachi harbour, just off Clifton, visible miles away to the incoming ships and the planes as well. If possible the words “Unity, Faith and Discipline” may be inscribed on it, and brilliantly lighted at night’.Footnote 108

Both India and Pakistan quickly produced national flags, either as adaptations of older ones or largely new, inspired by those of the parties that spearheaded the recent struggles for Independence. India’s was based on the Congress’s Swaraj flag, but with the spinning wheel replaced by the Ashoka Chakra or eternal wheel of law. The gradual production of this flag linked back to the 1931 Karachi Congress, which had passed a resolution on the flag, and the requirement for it to be ‘officially acceptable’ to the Congress. It was from this point that the issue of the ‘communal’ significance of its colours was perhaps most strongly and openly debated, with potential designs that were totally saffron eventually being abandoned for the tricolour: white representing Christian communities, green representing Muslims and saffron Hindus. The flag encapsulated debates about the material and symbolic role of Gandhi’s constructive nationalism: In 1931, it had been made of homespun cloth, with an image of the spinning wheel placed at the centre. By the time of Independence, the full image of a spinning wheel had been replaced by a martial sign of the conquering warriors of Ashoka – the Dharma Chakra – the wheel of cosmic order. When this replacement was proposed in July and August 1947, Gandhi expressed a sense of disappointment and concern that the spinning wheel had been lost.Footnote 109 However, typically he took the opportunity at a prayer meeting to turn his dismay into the positive point that ‘the country should have only one flag and everyone should salute it’. For Gandhi, the significance of the flag also surpassed simple questions of demographic symbolism and denoted ideas of belonging for minorities, particularly Muslims: before Independence, it had made him ‘very happy to hear that in the Constituent Assembly both Choudhry KhaliquzzamanFootnote 110 and Mohammad SadullahFootnote 111 saluted the flag and declared that they would be loyal to the National Flag. If they mean it, it is a good sign’.Footnote 112 And just before Independence, Pakistan’s incoming government adopted a flag very similar to that used by Muslim League, which had itself drawn inspiration from flags associated with the Sultanate of Delhi, the Mughal Empire and the Ottoman Empire, with the green representing Islam and the country’s Muslim majority while its white stripe symbolized religious minorities and minority religions. In the centre, the crescent and star – traditional symbols associated with Islam – denoted progress and light respectively.

National anthems took longer to be approved. With the handover of power looming, government officials in Bombay, for instance, had requested confirmation regarding what tune to play on 15 August 1947. On 11 August, they received the following reply: ‘In connection with the celebrations of the “Independence Day”, all collectors are informed that “God Save the King” should not be played or sung on the 15th August [but] there will no objection to “Vande Mataram”Footnote 113 being played or sung if so desired’. Though the chief secretary to the Political and Services Department of the Government of Bombay promised that ‘orders regarding the new national anthem [would] be issued in due course’, it took until January 1950 before India’s official choice – Jana Gana Mana – was adopted by the Constituent Assembly. Indeed, it is not clear what was sung officially at the intervening Independence Day celebrations of 1947–49. Pakistan faced its own musical headache when it came to finalizing its own national song. At the direct invitation of Jinnah, a first set of words was penned in 1947 by Jagannath Azad, a Punjabi Hindu, Urdu poet and scholar of Iqbal’s poetry.Footnote 114 Interviewed much later (in 2004), Azad recalled the circumstances under which he had been asked to write Pakistan’s national anthem:

In August 1947, when mayhem had struck the whole subcontinent, I was in Lahore working in a literary newspaper. All my relatives had left for India and for me to think of leaving Lahore was painful. My Muslim friends requested me to stay. On August 9, 1947, there was a message from Jinnah Sahib through one of my friends at Radio Pakistan Lahore. He told me ‘Quaid-i-Azam wants you to write a national anthem for Pakistan’ … I asked my friends why Jinnah Sahib wanted me to write the anthem. They confided in me that ‘the Quaid wanted the anthem to be written by an Urdu-knowing Hindu’.Footnote 115

In December 1948, in the wake of Jinnah’s death, for reasons that are not clear other than the Pakistani authorities’ likely desire for something written by a Muslim,Footnote 116 a search was started for a replacement anthem, and a National Anthem Committee was set up, comprising politicians, poets and musicians and initially chaired by the Information Secretary. Progress, however, proved to be slow. Following the first foreign head of state visit (by President Sukarno of Indonesia) in January 1950, when there had been nothing available to be played, renewed urgency was attached to the search. Members of the public now started to worry about Pakistan’s embarrassing lack of an anthem. As one letter writer to Dawn pointed out: ‘We want to sing our National Anthem full-throated and we – men, women and children – would like to stand-to-attention when its tune is played by our military band’.Footnote 117 Others agreed:

The National Anthem of a great country always represents the virility, ambition and spiritual urge of its people. After our religion it is one single factor which is capable of reinforcing our morale even in the worst circumstances. It can also be used to discipline our people whether they are students or workers in field or factory. It is a pity that although this is the third year of our existence the authorities have not so far been able to release the tune and the wordings of our National Anthem.Footnote 118

In 1950, the Committee eventually gave the go-ahead for music by Ahmed G. Chagla (approved the previous year) to be performed during a state visit by the Shah of Iran in March, and then the following August the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting officially approved new lyrics – written by the well-known poet Hafeez Jullundhri and chosen from over 700 submissions – with the complete anthem broadcast publicly for the first time on Radio Pakistan that month.Footnote 119

Pakistan, like India and other states that had won their freedom from colonial rule, evidently needed to remind its citizens that they belonged to a qualitatively different kind of political arrangement than had existed in the past. National days, parallel to those devised in India, represented one relatively straightforward way of getting this message across. Hence, 14 August – Pakistan’s Independence Day – became a key date in the annual calendar, when politicians and public were encouraged to celebrate the anniversary of Pakistan’s creation. In addition, 23 March – Pakistan Day – conveniently marked both the passing of the 1940 Lahore (or ‘Pakistan’) Resolution and later when the first Constitution came into effect in 1956. Jinnah’s official birthday – 25 December – was turned into a public holiday, as, from 1949 onwards, was the annual commemoration of his death (11 September). On these state occasions, politicians at national and provincial level issued suitably stirring messages via official press releases and through the media, with Radio Pakistan playing an important role as its reach expanded over the course of the 1950s. Though Jinnah was too unwell to speak directly to crowds gathered in Karachi to celebrate Independence Day in August 1948, his words of patriotic encouragement were relayed to by Liaquat Ali Khan, and then dominated newspaper headlines the following day:Footnote 120 as Jinnah reminded Pakistan’s new citizens, the establishment of the country was ‘a fact of which there is no parallel in the history of the world. It is one of the largest Muslim States …, and it is destined to play its magnificent part year after year, as we go on, provided we serve Pakistan honestly, earnestly and selflessly’.Footnote 121

But despite the specific rhetoric involved, Pakistan’s first anniversary celebrations were very like those taking place in India a day later, though perhaps rather more clearly focussed on military technology – a military tattoo, and a fly-by which dropped leaflets on the crowd (also officially and conveniently estimated at 200,000), followed the official summaries of the past year. Speeches focussed much more markedly on the adversity facing Pakistan from ‘enemies’ (viz. India), and the main reference to Pakistan’s future related to the establishment of a government operating ‘on Islamic principles’ of equality, fraternity and social justice.Footnote 122 With tension mounting over India’s policy towards the Princely State of Hyderabad (Deccan), Pakistani newspapers reported on Liaquat’s reference to how enemies had ‘conspired to paralyze the new state and how Pakistan had bravely weathered the storm’, on the existence of a ‘Sikh conspiracy’, the alleged conspiracy to destroy important papers and records, and the ‘presence of a certain element whose cult is to spread discord’.Footnote 123

According to contemporary observers, with little visible progress in terms of reorganizing the city’s administration, the Karachi authorities found themselves with their ‘hands full’ when it came to mounting the first anniversary celebrations: ‘The much heralded Refugee Rehabilitation Finance Corporation so far appear[ed] to have achieved nothing at all’, as one observer commented.Footnote 124 But refugee welfare remained a dominant theme on these state occasions, exploited by official rhetoric as well as challenged by the government’s critics. Time and again, the Pakistan government scheduled its release of information on refugee rehabilitation to coincide with the anniversary of Independence, taking the opportunity to outline the progress that it claimed was being made together with ambitious future projects intended to address any continuing problems.Footnote 125 In his 1953 Independence Day speech, Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra announced a scheme for the resettlement of some 43,000 refugee families in the federal capital, and appealed for public donations to help with the costs involved.Footnote 126

It was not just anniversaries of key moments in the creation of Pakistan that offered opportunities to enact and, in the process, reinforce the official identity of the new state. While members of Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly were finding it extremely hard to agree on what a ‘Muslim state’ would actually mean in practice, the religious calendar provided additional collective occasions for the authorities to exploit. In 1948, Liaquat and his colleagues were ‘lavish’ in their exhortation to the public to observe the month of fasting in the manner ‘befitting the largest State of Islam’.Footnote 127 In the run-up to Ramadan (the Muslim month of fasting) that year, the prime minister took the step of issuing an official injunction to Muslims to observe the fast in practice as well as in spirit: a move that caused a British observer to comment cynically that ‘this Islamic fervour on the part of Pakistan officials who, privately, and in some cases publicly also, are but moderate observers of the Quranic injunctions, is probably designed to steal the thunder of the Mullahs’.Footnote 128 The state authorities also made use of religious festivals – in particular Eid ul-Fitr at the end of Ramadan and Eid ul-Azha (that marked an important stage in the annual Hajj) – to deliver public messages about Pakistan’s identity as well as its progress, whether past, present or future. In August 1947, shortly after Independence, Jinnah used the occasion of Pakistan’s first Eid celebrations to remind its new citizens that

No doubt we have achieved Pakistan, but that is only yet the beginning of an end. Great responsibilities have come to us, and equally great should be our determination and endeavour to discharge them, and the fulfilment thereof will demand of us efforts and sacrifices in the cause no less for construction and building of our nation than what was required for the achievement of the cherished goal of Pakistan. The time for real solid work has now arrived, and I have no doubt in my mind that the Muslim genius will put its shoulder to the wheel and conquer all obstacles in our way on the road, which may appear uphill.Footnote 129

A couple of years later, the Prime Minister’s Eid message in July 1950, though less dramatic, promised an early imposition of a (long-awaited by some) refugee tax.Footnote 130 Refugee interest groups welcomed Liaquat’s assurance, but they also cautioned his administration against becoming ‘remote from those whose will it embodies’: while the state might want to impress outsiders with what Pakistan had achieved since Independence, ‘we cannot mould their judgement by pomp and pageantry’.Footnote 131 On the same day in Karachi, some 200,000 worshippers offered their Eid prayers in the open space surrounding Jinnah’s mazar (tomb): ‘From all parts of the city since early morning … crowds converged on the ground … thousands had to line themselves up on the road for the prayers … After the prayer was over nearly every Muslim from the congregation visited the resting place of the Father of Nation, the Quaid-i-Azam, and paid homage to his memory’.Footnote 132

Anniversaries and national days, however, could prove to be a double-edged sword by also creating space for critics of government to air their dissatisfactions: in Pakistan in 1950, while ‘the din of Independence Day oration was still echoing’, a Civil and Military Gazette editorial bluntly observed that ‘[a]t present, the League is, for the vast majority of the population, a name and not a particularly well-sounding name’.Footnote 133 In 1954, following a growing split between the party and the federal government, a group of Muslim League supporters turned the official Independence Day gathering in Karachi into a very public demonstration against the incumbent Prime Minister Mohamad Ali Bogra and his administration. The political atmosphere on the eve of this particular anniversary was undeniably tense. While the East Bengal governor had just prorogued the Legislative Assembly in Dhaka to prevent the provincial – United Front – ministry from being overthrown, students in Karachi were demonstrating in support of President Nasser in Egypt with a citywide strike planned for 16 August. Meanwhile, the Muharram season had reached its climax – significant, bearing in mind local Sunni-Shia friction – and, in addition, refugees and non-refugees in Karachi were hugely divided over the local police force.Footnote 134