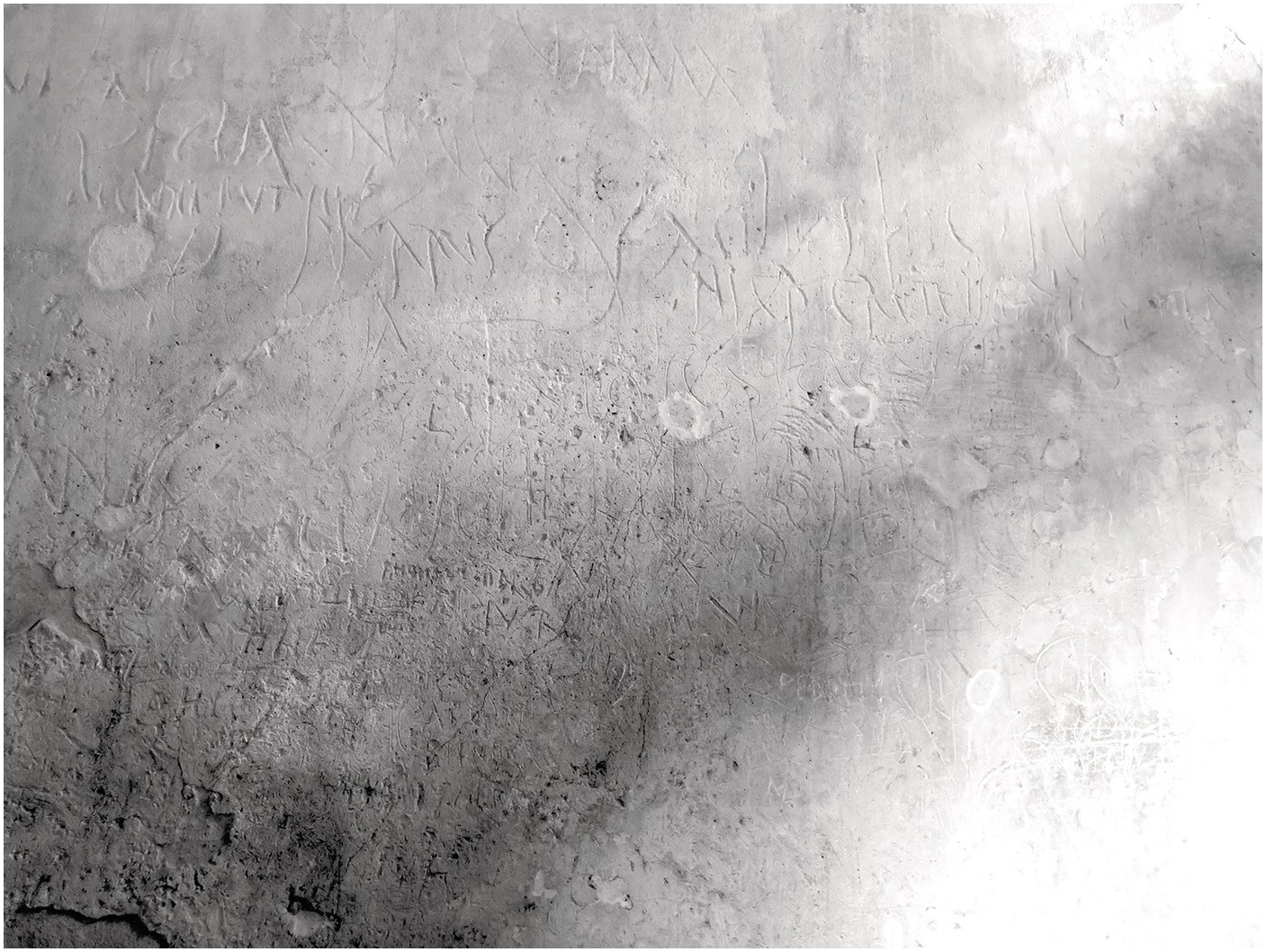

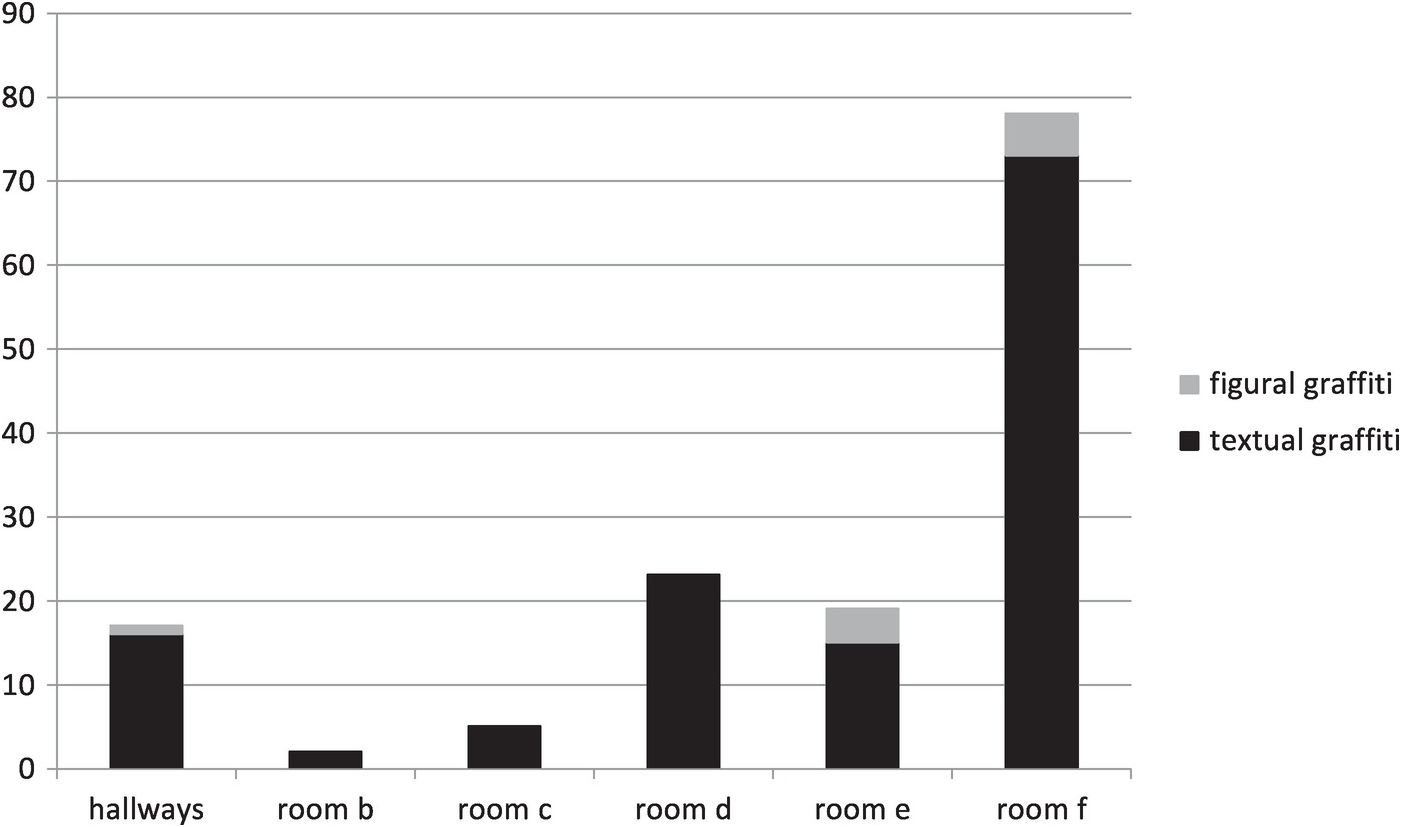

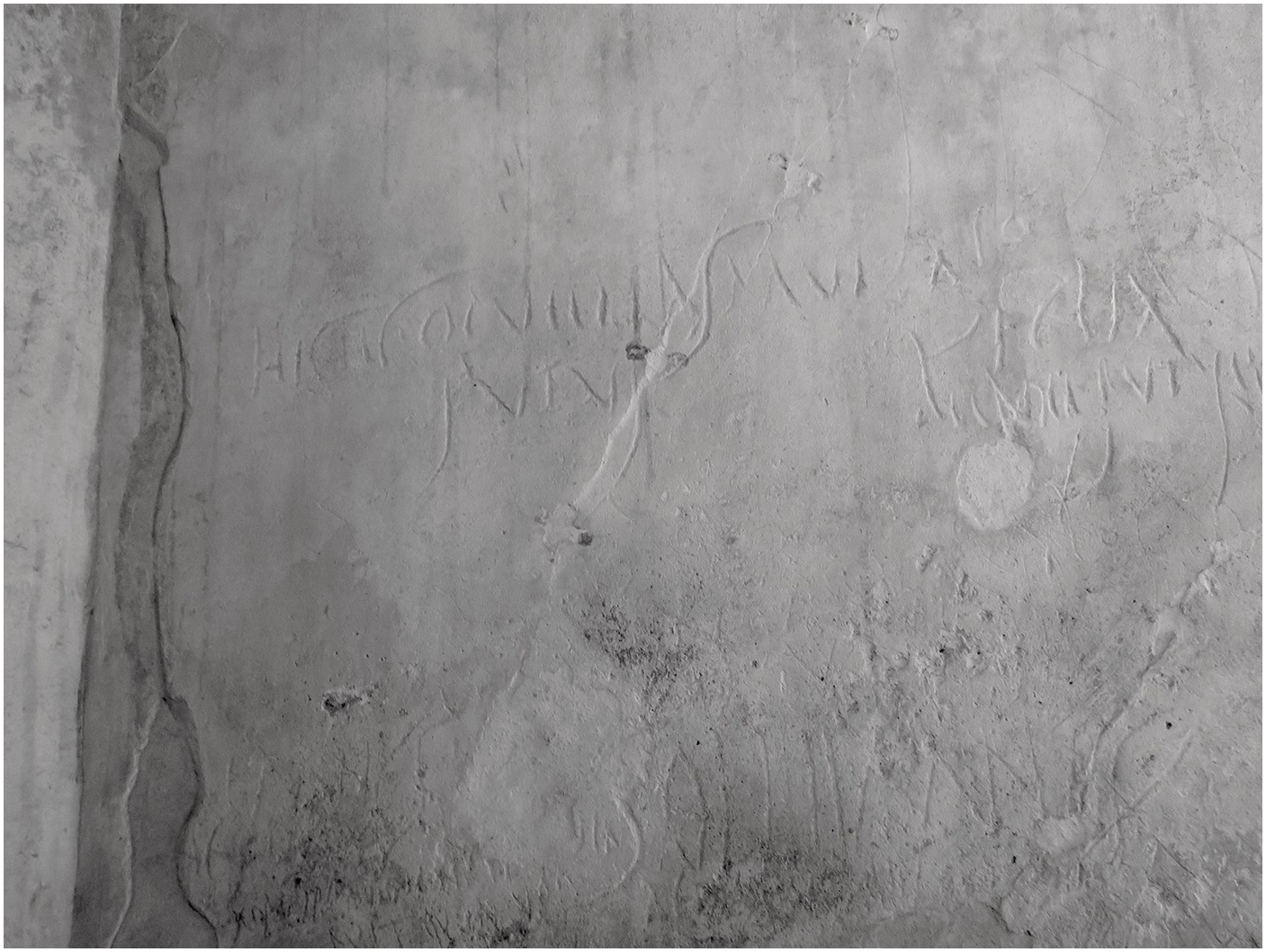

The nearly 150 texts and images of the purpose-built brothel – including sexual boasts, death notices, snippets of poetry, names, greetings, and drawings of ships, birds, and phalluses – comprise one of the largest clusters of graffiti anywhere in Pompeii (see Fig. 19).1 While early scholars were quick to characterize (and thus dismiss) these graffiti as obscene, only one-third of the structure’s graffiti contain explicit sexual content.2 Names, in fact, form the single largest category of graffiti in the structure – mirroring Pompeian graffiti more broadly3 – and have been amply studied by modern scholars seeking to understand how prostitution was organized in the brothel and at Pompeii more generally. The important work of James L. Franklin, Jr., Antonio Varone, Thomas McGinn, and Pietro Giovanni Guzzo and Vincenzo Scarano Ussani has tackled (though not resolved) aspects of the status and origins of those involved in Pompeian prostitution, as well as showing the possible connections that those in the brothel – both prostitutes and clients – had in the wider community.4

Among the most provocative of these findings are that some of the brothel’s clients and prostitutes were free (rather than slaves) – that is, their names are gentilicia or clan names, which were not given to slaves – and that one out of every five female names in the brothel is of a free woman.5 The prostitutes and clientele of the brothel are thus much more diverse in status than previously realized. As Varone notes, servile prostitutes whose earnings went directly to their owner or manager would have worked alongside prostitutes who had more freedom (or at least were less formally tied to a manager).6 Determining the ethnic origin of those in the brothel is much more difficult. It is tempting to read into the 8 percent of the brothel’s graffiti that are written in the Greek language or script,7 or the fact that nearly one-third of the names written in the brothel are of Greek origin,8 and posit that these reflect non-Pompeians or a large Greek population at the brothel.9 Heikki Solin, however, in no uncertain terms argues that neither Greek names nor the Greek script can identify ethnic Greeks at Pompeii.10 There is nevertheless clear evidence from other graffiti that the brothel attracted individuals from surrounding towns in addition to Pompeii.11

Another important finding is that the brothel’s prostitutes may have worked, or drummed up business, elsewhere at Pompeii.12 Perhaps the most evocative overlap of names inside and outside the brothel regards Myrtale, who is said to provide fellatio in one of the brothel’s graffiti (CIL 4.2268; 2271 also includes her name). This name reappears in a fresco from the Tavern of Salvius (VI.14.36) depicting a male and female figure facing one another, almost kissing, with the text nolo | cum Myrtale, “I don’t want to with Myrtale” (CIL 4.3494a), above them.13 We may never know if it refers to the same Myrtale as in the brothel, but the coincidence certainly should make us aware of the potential geographical and social reach that those who patronized and worked in the brothel may have had.

This corpus repays attention to its physical, rhetorical, and communicative features, as well.14 The inscribed images, along with other features such as fingerprints pressed into the wet plaster, suggest that a multisensory experience was available even to those with limited or no literacy, while the locations of the graffiti conjure a world of individuals clambering onto the brothel’s masonry platforms, with some rooms overwhelming their users with a cacophony of texts and images and other rooms remaining nearly mute. The wealth of names provides not only a prosopography of prostitutes and clients, but also a window into how these individuals crafted their identities for all to see. Finally, the diversity of texts and images – evoking a world not just of sex for sale but of commemoration, seafaring, and local town rivalries – suggests that the brothel functioned as a sounding board for at least a segment of the community.

Pompeian Wall-Writing Culture

Before we turn to the texts and images on the brothel’s walls, a few introductory remarks about Pompeian graffiti are in order. Scholars conventionally use the term “graffiti” to refer to texts and images scratched into Pompeian walls, since the term graffiti originally meant “little scratches” in Italian.15 The Romans, however, did not have a separate word to distinguish writing on walls from other types of writing.16 Moreover, scholars continue to illuminate the extent to which writing on walls at Pompeii was practiced by all strata of society, for all kinds of reasons, and in all types of places. Children, slaves, construction workers, household staff, women, and homeowners have all been shown as active participants in writing on walls.17 This diverse array of individuals drew ships, phalluses, faces, gladiators, and animals, and wrote texts ranging from self-referential witticisms to names, inventories, practice alphabets, greetings, slander, poems, games, and quotations from literature.18 It seems to have been commonplace and acceptable to write on nearly any type of wall, from the inside of houses to shops to civic structures.19 Rebecca Benefiel perhaps best illuminates this culture of wall writing through her discussion of graffiti within houses, arguing in one case that the homeowner has carefully inscribed a graffito into his own wall to welcome guests.20

While the literacy rate of the Roman Empire as a whole is hotly contested – William Harris argues for a rate as low as 15 percent – the robust epigraphic culture at Pompeii has generally been taken to indicate that Pompeians had comparatively high rates of literacy.21 We should keep in mind that this literacy may have been spread out unevenly, however: levels of literacy between, and even within, various categories of individuals at Pompeii may have varied significantly. For example, although there is evidence of literate women at all social strata,22 Roman boys were much more likely to have had formal schooling than girls, and thus generally, male literacy was in all likelihood higher than female literacy.23 Likewise, some slaves were educated to perform specific duties for their masters (who themselves might not be literate), but many slaves may have remained illiterate.24

Perhaps more importantly for understanding the brothel’s graffiti, scholars acknowledge that individuals could fall along a spectrum of literacy, from replicating letters without understanding them, to being able to read a little but not write, to being able to write a few words (such as one’s name), all the way to being able to compose and understand syntactically complex sentences.25 Franklin, for example, suggests that the large names in Pompeii’s electoral posters could have been “worried out even by the semi-literate” and that the abbreviations within posters “must have been intelligible to the voters if only by virtue of their constant repetition.”26 Ann Ellis Hanson and Benefiel have likewise highlighted the ability of those with limited literacy to copy (if poorly) short examples of texts written by others.27 The ability to draw images or marks on a wall likewise broadens the number and types of individuals (such as children and the illiterate) who were involved in graffiti production. From the outset, then, we ought to be open to the possibility of prostitutes and clients, men and women, and slaves and elites as potential writers and viewers of the brothel’s graffiti, while being sensitive to the ways in which an individual’s level of literacy might have affected their participation.28 To capture this range of literacies, as well as aspects of Pompeian vernacular and the influence of oral pronunciation on spelling, I present the graffiti below (and in all parts of the book) with minimal editorial interventions. This carries over into my translations, where I aim to preserve non-standard forms and errors.29

A Multisensory Experience

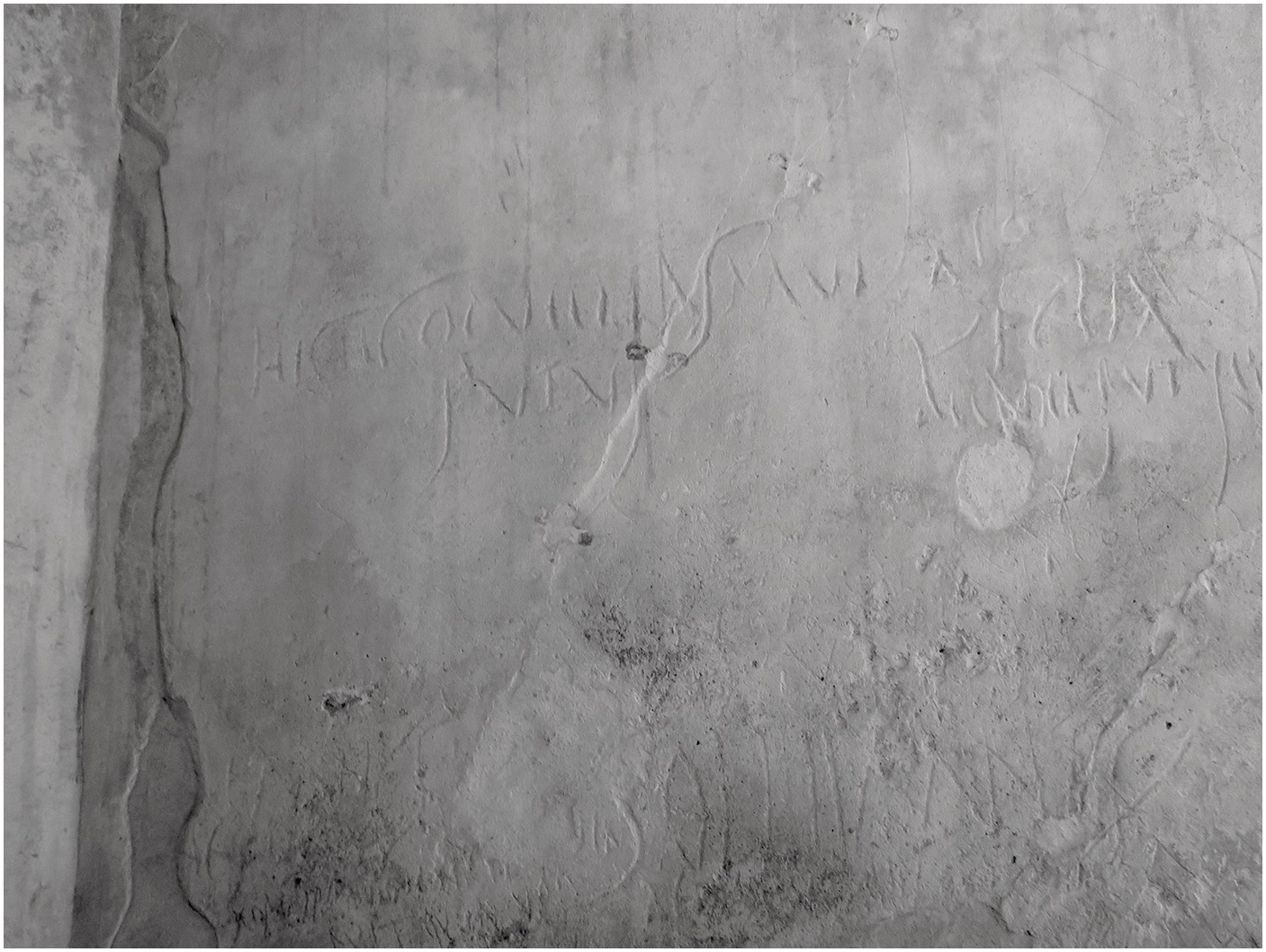

The brothel offered numerous ways – including touch, sight, and sound – for individuals of all levels of literacy to engage with the structure’s epigraphic environment.30 To start, individuals used the walls of the structure not only for writing texts but also for drawing images. A ship was drawn with numerous heavy linear strokes on the west wall of room f (Fig. 20), while small lines made with a sharp tool might indicate water or schools of fish below. 31 Three human profiles were drawn amid the tangle of textual graffiti; of the two that are still visible, one may have depicted a gladiator (Fig. 21), while the other incorporated parts of nearby textual graffiti for the back of the head (Fig. 22).32 On the north wall of room e, someone used careful, precise lines to delineate a bird clutching onto a branch with berries (Fig. 23),33 while the doorjamb of this room contains a row of short, vertical marks, from the center of which a set of closely spaced thin vertical lines descends (Fig. 24). These lines, in turn, are drawn over by a heavy wavy line. What this is meant to depict is unknown, but perhaps it was architectural in nature.34 Individuals also drew four phalluses, one of which ejaculates (see Fig. 62).35 The visual vocabulary of these figural graffiti speaks of seafaring, animals (maybe even a pet?), people (including a possible gladiator), and sex. All of these are common motifs in Pompeian figural graffiti,36 and thus the interests of those in the brothel mirror those of the wider community.

20. Graffito of a ship, west wall of room f. The futue of CIL 4.2200 Add. p. 215 (Feliclam ego hic futue, “I focked Felicla [= Felicula] here”) can be seen above the ship.

21. Graffito of a human profile near the doorway to room f, west wall of room f of the purpose-built brothel. The letters MPEI of Pompeianis (from CIL 4.2183 Add. p. 465: Puteolanis feliciter | omnibus Nucherinis | felicia et uncu · Pompeianis | Petecusanis, “Good luck to the Puteolans! To all the Nucherians [= Nucerians], luck! [But] an anchor for the Pompeians [and] the Petecusans [= Pithecusans]”) seem to have been written over the figure’s headgear (helmet?); the rest of the profile, facing left, is in the space below. CIL 4.2173 Add. p. 215 (Salvi filia, “daughter of Salvius”) can be seen at the bottom of the image, and at the left is the last word of CIL 4.2201 (Marcus · Scepsini ubique sal(utem), “Marcus [sends] greet(ings) to Scepsis everywhere”).

22. Graffito (CIL 4.2191: futui, “I fucked”) in the forehead of a human profile facing left, west wall of room f. The back of the figure’s head is formed by the graffito’s “i,” while the back of the figure’s neck is formed by the first “f” of CIL 4.2199 (Felicla ego f, “I f-ed [= fucked] Felicla [=Felicula]”).

Scratching graffiti – whether figural or textual – into a wall also brought an individual into close contact with the wall itself. An individual could leave deep or shallow marks, skinny or wide; one could write or draw over existing graffiti, or even just feel the marks left by others on the walls.37 Moreover, a number of additional marks suggest an abiding interest in the materiality of the wall. On the west wall of room f, coins were pressed into the wet plaster creating multiple circular impressions, at least one of which was decipherable shortly after excavation (this is, in fact, what dates the brothel’s remodeling to 72 CE).38 The marks left by fabric pressed into the wet plaster can also be seen not far below the drawing of the ship, and a set of parallel bands with soft, rounded edges on the same wall may have been made by someone running their fingers horizontally over the wall when the plaster was still wet.39 This same wall also contains a series of marks resembling ( ) ( ) ( ) X X, some of which – the roughly circular shapes – reappear on the east doorjamb of room e (see bottom right corner of Fig. 32). The north wall of room e also contains a rough line of circular impressions that may be fingerprints made in the wet plaster (Fig. 25).40

25. Circular impressions (possibly fingerprints), north wall of room e.

The visual environment created by these graffiti, as one can see in Figure 19, could be complex and crowded. In addition to the texts, images, and marks already mentioned, numerous solitary lines and letters added to the visual chaos.41 Moreover, the visual experience of the graffiti would change as the day progressed and natural light from the south- and east-facing windows moved over the walls, bringing some graffiti into relief while others faded from view. The use of lamps – as mentioned in the previous chapter, a single-nozzle terracotta lamp was found in the structure – would have added a further visual dynamic, creating halos of light and dark, and highlighting some graffiti while plunging others into darkness. The flickering could at times catch on the sharp edges of the graffiti and make them more readable or, as Benefiel has recently argued, give a sense of motion to the otherwise static incisions.42 When this flickering light fell upon the figural graffiti, phalluses could seem to grow and ejaculate (or on the contrary, to shrink), faces to express emotions, ships to sail, birds to flutter. The brothel’s graffiti thus offered a vibrant, ever-changing visual experience.

In addition, one could participate in this discourse by reading aloud graffiti already on the wall, or hearing another person’s recitation (as we think that reading was often conducted aloud in antiquity).43 Hearing others read aloud textual graffiti made these texts accessible to all, and after listening, subliterate individuals could then coopt these recitations and rearticulate the statements as their own, for their own purposes. In sum, the physical and sensory qualities of the brothel’s graffiti made it possible even for non-literate individuals to participate in the conversations reflected in, and created by, these graffiti.

Distribution and the Use of Space

As mentioned in passing above, some of the rooms of the brothel have dense concentrations of graffiti, while others were left nearly bare (see Figs. 26 and 27), raising questions about what can account for such an uneven distribution. Room f contains more than half of the structure’s graffiti, with seventy-three textual graffiti in addition to drawings of two phalluses, two human profiles, and a ship. When combined with the twenty-three textual graffiti in room d, these rooms closest to doorway 18 together account for over two-thirds of the brothel’s graffiti.44 For comparison, room b has only two graffiti.

27. Distribution of graffiti by wall; the numbers in bold indicate total number of textual graffiti on each wall, with the numbers in parentheses indicating CIL numbers.

What might account for the vast discrepancies between the eastern rooms (d and f) and the western rooms (b, c, and e)? One of the two scenarios Varone suggests is that the prostitutes in the western rooms did not allow individuals to write graffiti.45 However, Varone does not put forward a motive for preventing graffiti, nor is one readily apparent, especially given the pervasive writing culture at Pompeii. Nor is it clear why graffiti would be prevented in the western rooms and not the eastern rooms. Varone’s alternate explanation – and the one he admits is more likely – is that the eastern two rooms were used much more often than the other rooms.46 As Mary Beard suggests, this may be because they are the first rooms that clients would reach on entering the structure from doorway 18,47 though perhaps it is not a coincidence that room f is the largest room, and that both rooms d and f have two windows each that would provide fresh air and natural light, making the environment more pleasant and making incised texts and images easier to see.48

If the eastern two rooms attracted more graffiti because they were used more often, it would seem that the brothel was not fully staffed or not fully booked, since we would imagine a more even distribution of graffiti if all rooms were equally put to use.49 The western rooms might have been left vacant much of the time, perhaps making them available to walk-in couples wanting to rent a room for a tryst (as Varone suggests) or to the brothel’s prostitutes for resting when not with a client.50 Perhaps the manager kept tabs on both prostitutes and clients from one of these less heavily inscribed rooms.

Or, to posit a different explanation for the graffiti’s distribution, perhaps the eastern rooms were waiting rooms where the brothel’s manager or one of the prostitutes would take a client’s money and socialize with him – including reading and writing graffiti – before and after sex. In that case, the sexual activity itself may have taken place in one of the western rooms. At the very least, even if a definitive solution eludes us, individuals must have had the time, desire, and ability to write graffiti in the rooms closest to doorway 18, and one or more of these factors may have been lacking in the other set of rooms.

The distribution of graffiti on certain walls, to the exclusion or near exclusion of other walls, also bears notice (see Fig. 27). Many more graffiti were written in areas that permitted standing up and moving around than in areas requiring one to be (relatively) static (that is, sitting or reclining on a masonry platform). In room f, for example, there is a marked absence of graffiti behind the platform on the south wall of the room, despite the abundance of texts on the east and west walls.51 Likewise, in room d, only four of the twenty-three graffiti were written in the area of the masonry platform (two above the foot of the platform and another two directly behind the platform). Doorjambs, on the other hand, were favored spots: the only two graffiti in room b were written on the western doorjamb; three of the five graffiti in room c are on its western doorjamb; and three graffiti and the architectural (?) drawing can be seen on the eastern doorjamb of room e (Fig. 24 and Fig. 32).52

Graffiti in these areas of movement – whether on doorjambs that one would pass entering and exiting a room or in the open areas of the rooms themselves – would have offered an interactive visual and kinesthetic experience.53 As an individual moved through these spaces, encountering these texts and images from numerous locations in space, the graffiti might become more visible as raking light from certain angles would catch on the edges of the scratches and incisions. The connections between an individual graffito and those around it would also move with the viewer, allowing graffiti to take part in multiple, shifting conversations depending on one’s perspective.

The height of the graffiti can likewise provide information about how bodies were interacting with the built environment of the brothel. For the most part, the graffiti were written at roughly eye level from a standing position, though in some cases, individuals contorted and stretched their bodies to write on the walls. For example, several are located high enough where one would need to stand on the masonry platform to write them. This is the case, for example, with two graffiti on the north wall of room e (see Fig. 28): hic ego cum veni futui | deinde redei domi, “When I came here, I fucked, and then I returned home” (CIL 4.2246 Add. p. 465), and Bellicus hic · futuit quendam | [l]uculentissim[e] fut[ui], “Bellicus fucks here a certain one. [I] fuck[ed] most [spl]endid[ly]” (CIL 4.2247 Add. p. 215; note that all graffiti with futuit can be translated as either present tense [“fucks”] or past tense [“fucked”]). The former was written nearly 7 feet from the floor, the latter a few inches below.54 As the platform in this room does not abut the north wall, the writer would have had to stand at the very foot of the platform and reach across and above to create these graffiti.55 Likewise, the height (nearly 6 feet off the ground) of Iias cum Ma|gno ubique, “Iias [= Ias] with Magnus everywhere” (CIL 4.2174), on the west wall of room f, led Fiorelli to believe that it was written by someone standing on the room’s platform (see Fig. 29).56 The awkward split of the name Magnus, moreover, is not because space was lacking after the first two letters – there is ample untouched wall space – but rather because it seems that this was the farthest the writer could reach from the platform, and thus he or she had to continue the name on a second line. Hic ego puellas multas | futui, “Here I fucked many girls” (CIL 4.2175), was also written from a standing position at the head of the platform in room f, but in this case was carefully centered above the platform (see Fig. 30).57 Thus, at least some individuals seem to have felt free to climb on top of the masonry platforms.

28. Locations of graffiti, north wall of room e: CIL 4.2246 Add. p. 465 (hic ego cum veni futui | deinde redei domi, “When I came here, I fucked, and then I returned home”) and CIL 4.2247 Add. p. 215 (Bellicus hic · futuit quendam | [l]uculentissim[e] fut[ui], “Bellicus fucks here a certain one. [I] fuck[ed] most [spl]endid[ly]”).

29. Locations of graffiti, west wall of room f: CIL 4.2174 (Iias cum Ma|gno ubique, “Iias [= Ias] with Magnus everywhere”), CIL 4.2175 (hic ego puellas multas | futui, “Here I fucked many girls”), CIL 4.2185 (S[ol]lemnes | b[e]ne futues, “S[ol]lemnes [= Sollemnis?], you fock w[e]ll”), and CIL 4.2188 (Scordopordonicus hic · bene | fuit · quem · voluit, “Scordopordonicus fuks well here who he wished”).

30. Detail of graffito (CIL 4.2175: hic ego puellas multas | futui, “Here I fucked many girls”), west wall of room f. Above the letters TAS at the end of the first line are the first three tall letters of the beginning of CIL 4.2174 (Iias cum Ma|gno ubique, “Iias [= Ias] with Magnus everywhere”), and below the same is CIL 4.2176 (Felix | bene futuis, “Felix, you fuck well”). Underneath that graffito, in turn, are the first six letters (inscribed very lightly) of CIL 4.2179 (calos Paris, “beautiful Paris”). In the bottom half of the photograph are, on the left, CIL 4.2185 (S[ol]lemnes | b[e]ne futues, S[ol]lemnes [= Sollemnis?], you fock w[e]ll”) and below that CIL 4.2188 (Scordopordonicus hic · bene | fuit · quem · voluit, “Scordopordonicus fuks well here who he wished”); on the right is CIL 4.2186 (Sθllemnes | bene futues, “Sollemnes [= Sollemnis?], you fock well”).

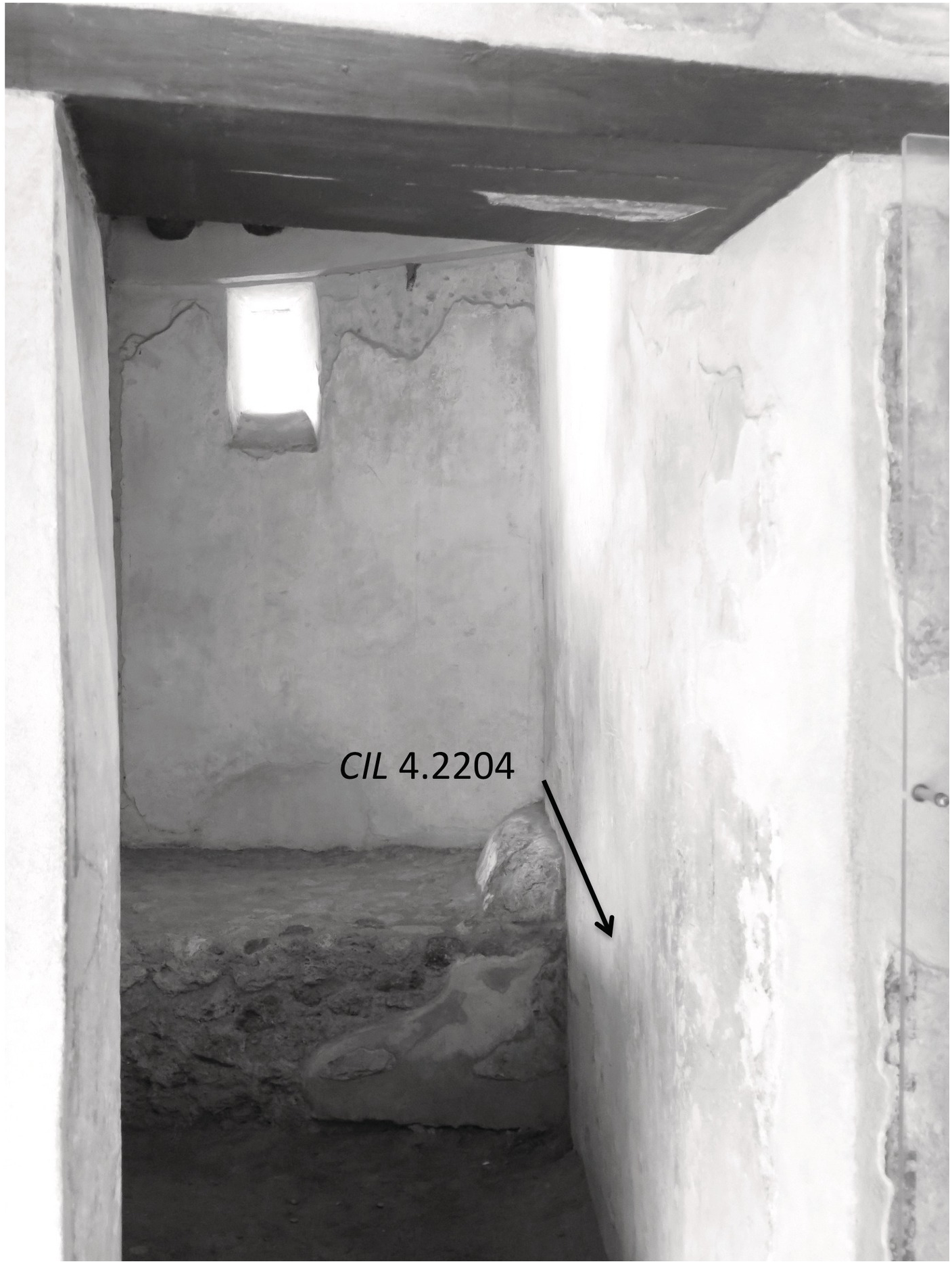

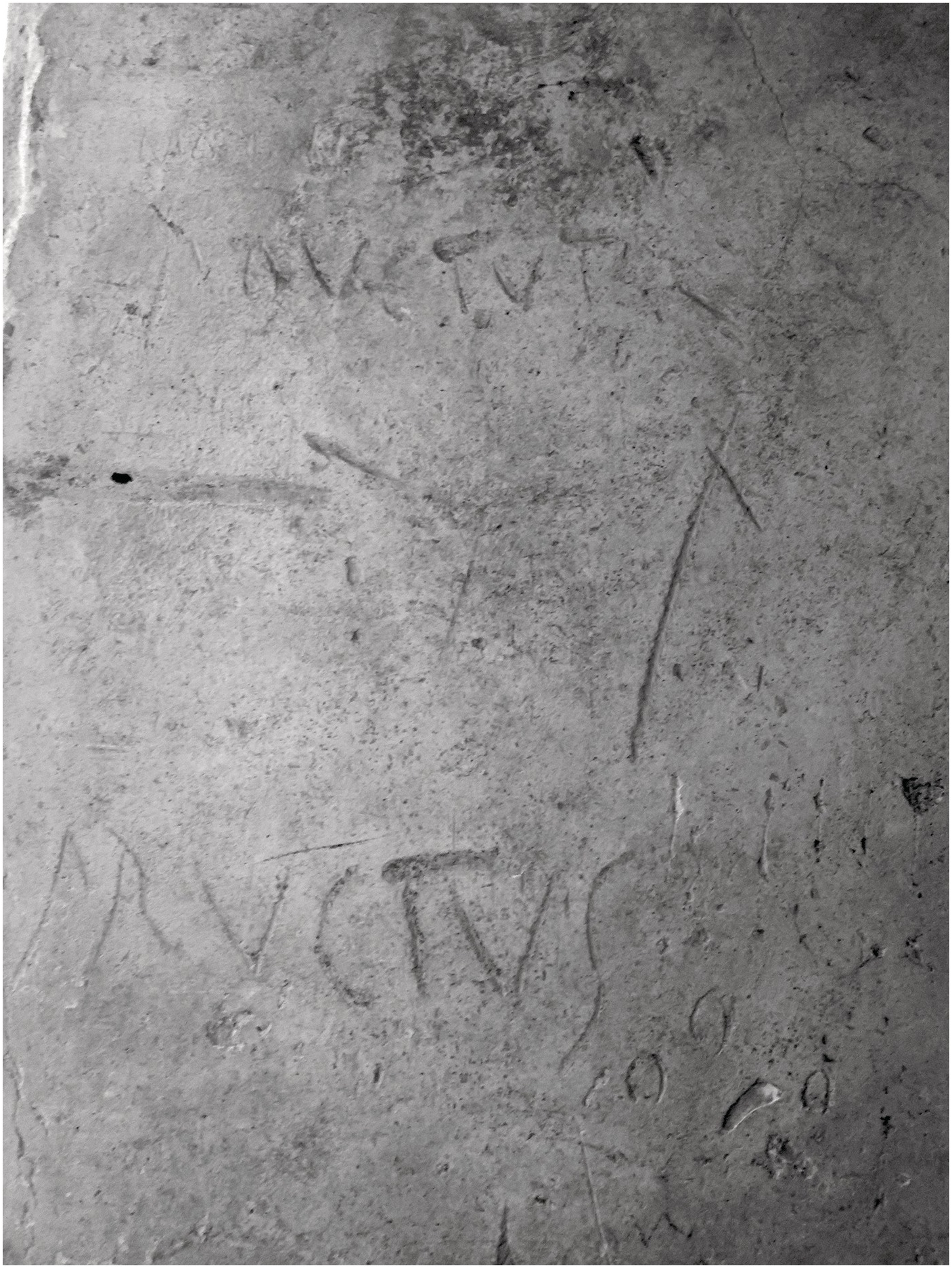

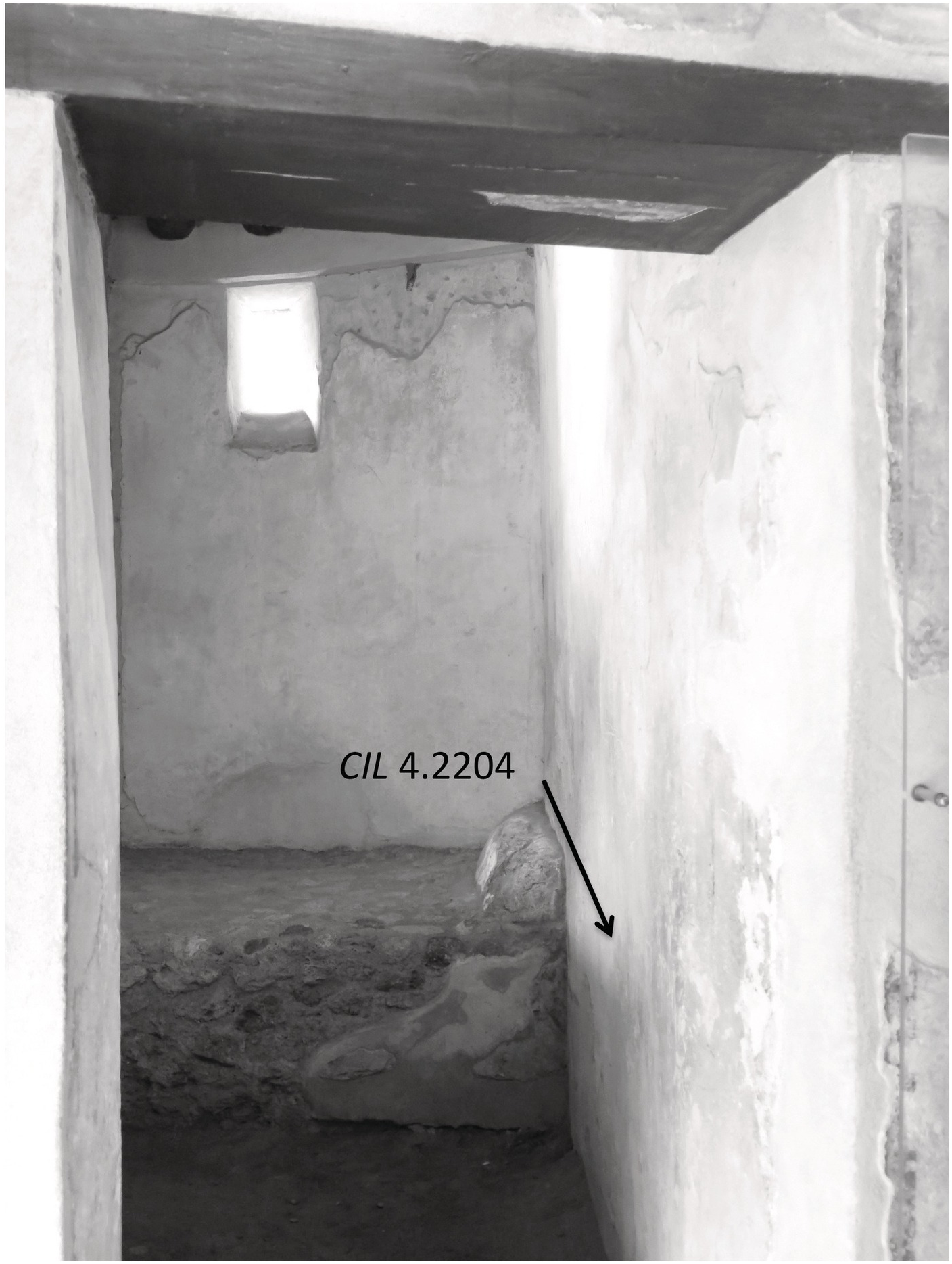

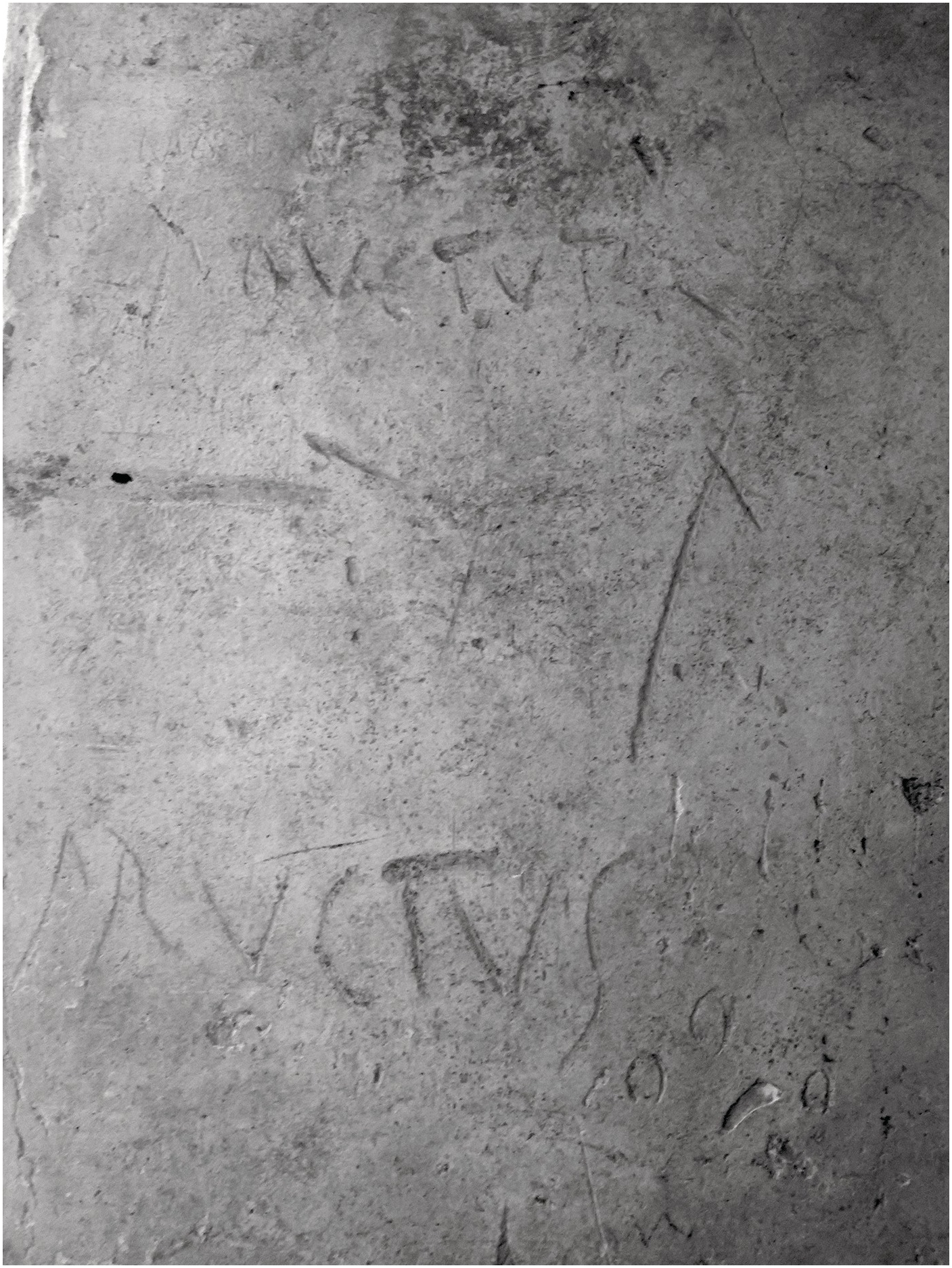

Other graffiti seem to have been written by someone reclining, sitting, or kneeling on the platform. This was probably the case with S[ol]lemnes | b[e]ne futues, “S[ol]lemnes [= Sollemnis?], you fock w[e]ll” (CIL 4.2185), and beneath it, Scordopordonicus hic · bene | fuit · quem · voluit, “Scordopordonicus fuks well here who he wished” (CIL 4.2188), written in room f less than 2 feet above the platform and starting in the corner (see Fig. 29).58 Only a few graffiti were written low to the ground, notably, Μόλα · φουτοῦτρις, “Mola the fucktress” (CIL 4.2204; note that all graffiti with a name and title could also be translated as “x [is] a y,” or in this case, “Mola [is] a fucktress”), which is less than 3 feet from the ground (Fig. 31).59 This suggests a scenario of someone kneeling or sitting on the floor, or perhaps bending down at an awkward angle. In all, these heights indicate that prostitutes and clients were engaging actively with the architecture of the structure.

As David Newsome reminds us, spaces with writing in them “do not simply respond to existing patterns of movement, but generate and sustain new ones.”60 In this way, the brothel’s graffiti not only reflect patterns of movement, but inspire (and even constrain) future interactions. The proliferation of texts and images in the rooms closest to doorway 18 may have drawn more individuals to these spaces and encouraged them to linger longer, moving along the walls to see the mass of graffiti written there.

Crafting Personas

While studying inscriptions and graffiti from a prosopographical point of view has a long history – and has been applied already to the brothel’s graffiti – examining graffiti through the lens of literary theory is a recent trend. As Craig Williams explains this approach, “[By] paying attention to recurring words, images, themes, noting what is largely or entirely absent, asking ourselves what kinds of actions and behaviors are praised, blamed, or made the subject of jokes, and with what words, we can consider what the graffiti suggest about the cultural systems of meaning shared by their readers and writers.”61 In other words, we should be attuned to “how people writing in this medium represented what they and others did, or were, or wanted.”62 As part of this approach, we should acknowledge the polysemous nature of graffiti: not only can they lie, create fictive personas, and play tricks on readers, as Williams and others have begun to show,63 but they could have different meanings to various individuals.

Most apparent in the brothel’s graffiti is the popularity of inscribing names (or personas), as can be discerned first of all by the sheer number of names present.64 Varone counts 88 distinct names referred to a total of 141 times in the brothel, and only 18 out of all of the brothel’s graffiti lack names.65 Moreover, 27 names appear more than once in the brothel,66 and while it is certainly possible that there were, say, three different individuals named Synethus who frequented the establishment, scholars believe that the small space of the brothel makes it probable that graffiti with the same name do refer to the same individual.67 The name Fructus, for example, has been written three times on the east doorjamb of room e, seemingly by the same individual (CIL 4.2244–2245a; see Fig. 32, but note that the name is visible only twice in the photograph). The names Victor (“Mr. Conqueror”) and Victoria (“Ms. Conqueror”) fittingly dominate all others with six appearances each. Statements about Victor could be seen on the north and east walls of room f (CIL 4.2209 and 2218 respectively), on the north and east walls of room d (north wall: CIL 4.2258 and 2260 Add. p. 216; east wall: 2274 Add. p. 216), and at the back of the hallway (CIL 4.2294).68 The appearances of Victoria, on the other hand, cluster in a group on the east wall of room f, and engage in a lively debate (see pp. 123–124).69 It seems likely, then, that Victoria worked out of room f, though Varone’s analysis of the spatial distribution of names shows that, in general, the rooms were probably used by multiple prostitutes and that the same prostitute could work out of different rooms.70 In all these cases of multiple appearances, attention is drawn to the person named.

In other cases, a name appears in more than one language, suggesting – if the same person wrote all of the statements – a desire both to communicate to as many potential readers as possible and to show off one’s knowledge of multiple languages. Above the platform in room e, for example, someone wrote the name Syneros in large, careful letters (CIL 4.2252; see Fig. 33); written next to it, in letters of the same size and carefulness but in Greek, is Ϲυνέρωϲ | καλὸϲ · βινεῖϲ, “Syneros, you fuck good” (CIL 4.2253; see Fig. 33 and p. 137).71 A similar situation may have been the case with two attestations of the name Marcus on the west wall of room f. The name appears once in Latin (CIL 4.2201), while also appearing close by in the (nearly defunct!) native Oscan language (see the notes of CIL 4.2200 Add. p. 215).72

33. Detail of graffiti, east wall of room e: CIL 4.2252 (Syneros) and CIL 4.2253 (Ϲυνέρωϲ | καλὸϲ · βινεῖϲ, “Syneros, you fuck good”).

While the “reality” behind Syneros, Marcus, and others may not be recoverable,73 we can still explore how people chose to depict themselves and others. In some cases, a fuller persona is communicated by the addition of adjectives to names. For example, an individual’s sexual acts (or predilections) could be turned into a title and appended to his or her name. A certain Phoebus is specified as a pedico, one of two nouns (the other being pedicator) meaning “ass-fucker,” in a graffito on the west wall of room f (CIL 4.2194 Add. p. 465),74 while in the hallway Epagathus is called a fututor, “fucker” (CIL 4.2242; for more on clients’ boasts, see pp. 101–106). The claim (mentioned briefly above) that Mola is a φουτοῦτρις, “fucktress” (CIL 4.2204), extends over nearly a meter of wall space on the west side of room f, and Murtis is said to be a felatris, “suktress,” in a graffito at the back of the hallway (CIL 4.2292).75 A couple of graffiti refer to physical traits, as in the description of two males, Paris and Castrensis, as calos, “beautiful” (CIL 4.2179 and 2180; see further pp. 135–136, where I suggest they might be male prostitutes).76 The oft-mentioned Victoria is even represented as a victrix, “conqueress,” in a greeting addressed to her (CIL 4.2212 Add. p. 215).

While the descriptors just mentioned are tied to the actions or appearance of the physical body – fitting, perhaps, for an establishment where bodily interactions (among other types of interactions) were bought and sold – some representations highlight others aspects of identity. One example, from the east wall of room d, seems to be a proclamation of local identity: Lucrio | amasuc[--] | Sarnesis “Lucrio … from Sarno[?]” (CIL 4.2267). In another example, from the west wall of room f, someone wished to specify that the occupation of Phoebus who optume futuit, “fucks best,” was making perfume (unguentarius; CIL 4.2184 Add. p. 215); this may or may not be the same Phoebus who is said to be a pedico, “ass-fucker” (CIL 4.2194 Add. p. 465), on the same wall, or the Phoebus who is mentioned as a bonus futor, “good fukr” (CIL 4.2248 Add. p. 215), on the north wall of room e. A certain Restituta’s character is featured in a graffito on the west wall of room f that refers to her as bellis moribus, “with charming ways” (CIL 4.2202 Add. p. 465).77 This was a compliment that apparently resonated with prostitutes, as it often appears in conjunction with a price.78 If the reading of CIL 4.2173 Add. p. 215, on the west wall of room f near the doorway, is in fact Salvi filia, “daughter of Salvius,”79 this would be a unique case in the brothel where familial relations were highlighted at the expense of the name of the woman herself, making readers aware that individuals in the brothel had identities and families outside the brothel.80 These additional details about individuals – their origins, occupations, character, possibly their family associations – situated the prostitutes and clients within the wider community.

Furthermore, we may be able to interpret the three profiles drawn on the walls of the brothel as belonging to the phenomenon of inscribing personas. On the west wall of room f near its doorway, someone drew a human profile facing left wearing headgear (Fig. 21).81 Martin Langner classifies the profile under gladiatorial imagery, and gladiatorial graffiti were very common indeed at Pompeii.82 It may even be that this profile provoked someone to inscribe a graffito about local town rivalries (CIL 4.2183 Add. p. 465; discussed more below) over the headgear of the profile.

Another human profile was drawn on the same wall around the graffito futui (CIL 4.2191), so that the statement “I fucked” can be read clearly on the figure’s forehead (Fig. 22; see further p. 126). The profile must have been inscribed after the text, since it makes use of the “i” of futui for the back of the head; in addition, it reuses the first “f” of Felicla ego f, “I f-ed [= fucked] Felicla [= Felicula]” (CIL 4.2199), for the same purpose.83 Thus we have an example of figural graffiti clearly engaging with textual graffiti already on the wall, and in a way that seems to personalize the anonymous statement “I fucked.”

A third profile was noted by CIL on the north wall of room e, apparently near the graffito (referred to briefly above) stating Phoebus | bonus futor “Phoebus the good fukr” (CIL 4.2248 Add. p. 215).84 Even if the profile were still visible, its connection to the textual graffito might still be unclear. Perhaps the profile was drawn to further identify Phoebus by means of physical characteristics, though perhaps there was no intended connection.85 Regardless, the human profiles as a whole represent another way of participating in the larger trend of proclaiming personas, and a way that even illiterate individuals could partake in (through inscribing profiles) and appreciate (through viewing the drawings).86

The role of graffiti in proclamations of identity or persona comes into further relief if we apply Greg Woolf’s view of inscribed Roman objects – namely, that these are “objects in which personhood is inscribed, stored, communicated and shared” – to inscribed walls, as well.87 If we broaden Woolf’s claim that objects inscribed with someone’s name indicate that “writing [one’s name, especially] is a powerful means of extending one’s self, of investing it in objects and (through their use) of expanding one’s participation in the world,” we can see how scratching one’s name (or persona) into the wall was a way of extending – both spatially and temporally – one’s presence in the brothel.88

In light of this view, the breakdown of the brothel’s graffiti by gender becomes particularly interesting: the epigraphic environment of the brothel was disproportionately gendered male. Varone notes that male names comprise nearly two-thirds of the total occurrences of names,89 and while epigraphic promiscuity was not restricted to one gender, as seen above with multiple appearances of the names Victor and Victoria, repeated male names outnumber repeated female names by sixteen to ten.90 While some of the male names might belong to male prostitutes (see further Chapter 8), many would belong to clients. Thus, even though clients’ actual presence in the brothel would have been more transitory than that of prostitutes, their epigraphic presence overwhelmed that of the workers.

Finally, a graffito written above the masonry platform in room f is a valuable reminder of the types of play that these graffiti might exhibit: Scordopordonicus hic · bene | fuit · quem · voluit, “Scordopordonicus fuks well here who he wished” (CIL 4.2188). While the formula hic bene futuit was used often in the brothel, the name Scordopordonicus is unique both at Pompeii and more widely. Crafted from two different Greek stems, the name can be translated roughly as “Mr. Garlique-farticus.”91 We see in this how certain formulas became so common that the expectations of readers could be played with to humorous effect: perhaps there was a client known for his flatulence problem, or, since the graffito offers no further identifying features about Scordopordonicus, perhaps any client could be framed as a potential garlic-farter. While the name Scordopordonicus calls attention to its stagecraft with its unprecedented combination of root words, other more common names might have been read as stage names in the context of the brothel. It is possible that Victoria was a stage name giving her an aura of “victory” in the brothel; that Fortuna and Fortunata might have been meant to feel “lucky” themselves or bring luck to others; and that Mola was a “grindstone” in bed (see further pp. 118–119).

Community Message Board

The brothel’s graffiti were also used to convey news and messages and, in the process, gave rise to certain affective communities. Town rivalries, the death of community members, and greetings were all written on the walls for others to read.

Perhaps best known is the expression of local town rivalries in room f near the doorway.92 Written in large, clear letters that could be seen from doorway 18, it begins Puteolanis feliciter | omnibus Nucherinis | felicia, “Good luck to the Puteolans! To all the Nucherians [= Nucerians], luck!” (CIL 4.2183 Add. p. 465). Because the wishes for luck are expressed with different grammatical constructions, Benefiel thinks that we already have two different individuals at work.93 As can be seen in Figure 34, someone else picked up after felicia and added et uncu · Pompeianis, “[But] an anchor for the Pompeians,” on the same line, and finally, on a fourth line, another individual added in smaller letters Petecusanis, “[and] the Petecusans [=Pithecusans].”94 These rivalries came to a head during an incident in 59 CE when a riot broke out in Pompeii’s amphitheater between Pompeians and the neighboring Nucerians during what may have been gladiatorial spectacles.95 As represented by the early second-century CE historian Tacitus, the thoroughly routed and wounded Nucerians tattled to Rome, and the Senate in response banned (gladiatorial?) spectacles at Pompeii for ten years. Advertisements from the last decade before the eruption of Vesuvius show that at least some kinds of spectacles (beast hunts and athletic competitions, for example) continued to take place, and local rivalries certainly did not cease.96 In the case of our graffito, up to four different individuals at four different moments – perhaps one immediately after the other, perhaps separated by days or month or even years – chose this space to express their wishes for good (or bad) luck to their favored (or rival) town. Moreover, parts of the texts were written over the profile of a possible gladiator discussed earlier (Fig. 21), and thus the location of this articulation of rivalries may have been deliberate.

34. Detail of graffito (CIL 4.2183 Add. p. 465: Puteolanis feliciter | omnibus Nucherinis | felicia et uncu · Pompeianis | Petecusanis, “Good luck to the Puteolans! To all the Nucherians [= Nucerians], luck! [But] an anchor for the Pompeians [and] the Petecusans [= Pithecusans]”), west wall of room f. The end of CIL 4.2201 (Marcus · Scepsini ubique sal(utem), “Marcus [sends] greet(ings) to Scepsis everywhere”) can be seen at the bottom of the photograph.

The deaths of at least two individuals were also commemorated inside the structure, and in ways that involved multiple individuals as writers or readers. In one case, from the west wall of room f, the notice is brief and direct: Ikarus Θ, “Ikarus, dead” (CIL 4.2177).97 The theta deserves further attention, as it was written with shallower, wider strokes than the name itself. This suggests that it was added by someone else at a later date, perhaps (one would hope) after Ikarus died, and thus points to a desire to keep the community informed of Ikarus’s status.98 Another death notice, from the north wall of room d, portrays a vivid narrative: Africanus moritur | scribet · puer Rusticus | condisces cui dolet pro Africano, “Africanus is dying. The boy Rusticus writes. You will learn who mourns for Africanus” (CIL 4.2258a). If, as I have done in the translation, we take condisces as a second-person verb (“you will learn,” rather than condisce[n]s, “schoolmate,” as some scholars think),99 the reader is coopted into the grieving process (for more on this graffito, seemingly written by a male prostitute, see pp. 132–133).

In addition, both prostitutes and clients used the brothel’s walls for sending and receiving greetings.100 Ias Magno salute, “Ias [sends] greeting to Magnus” (CIL 4.2231 Add. p. 215), shouts across a meter of the east wall of room f with the first “I” a whopping 45 centimeters tall, overshadowing all other graffiti on the wall. Ias was a common name in Latin literature for a female prostitute, and thus we may have a prostitute writing to her client.101 We have already seen this pair, in fact: both are mentioned on the opposite wall in a graffito written by someone reaching from the platform (Iias cum Ma|gno ubique, “Iias [= Ias] with Magnus everywhere” [CIL 4.2174]). Only two other greetings include the names of both the sender and recipient. Marcus – briefly mentioned above for his multilingual appearances – left a warm greeting to the woman Scepsis on the west wall of room f: Marcus · Scepsini ubique sal(utem), “Marcus [sends] greet(ings) to Scepsis everywhere” (CIL 4.2201). On the north wall of room f, Sabinus Proclo | salutem, “Sabinus [sends] greetings to Proclus” (CIL 4.2208), leaves us to speculate about the relationship between the two individuals, since neither male name is mentioned elsewhere in the brothel. Perhaps this was a greeting between two clients, or a prostitute and client, or even two prostitutes.

In another five greetings, only one party is named, expanding the interpretive possibilities.102 In calos Castrensis s(alutem), “Beautiful Castrensis [sends] gr(eetings)” (CIL 4.2180; west wall of room f), the open-ended greeting invites readers to imagine themselves or others as the recipients. In other cases, we must imagine the sender (who remains anonymous), as in a greeting to one of the female prostitutes (mentioned earlier) on the east wall of room f, victrix Victoria va(le), “Conqueress Victoria, hey!” (CIL 4.2212 Add. p. 215).

Graffiti such as these that include greetings, show multiple hands at work, or convey conversations in progress speak to the time that individuals spent creating, reading, and responding to these messages. This outlay of time and effort has implications – like the distribution of graffiti – for the economics of the brothel. Rather than aiming to get clients in and out as fast as possible, the brothel allowed individuals to linger, peruse previous graffiti and perhaps experience moments of discovery at new additions, and to leave one’s mark.

Moreover, these graffiti were not just static traces of (real or imagined) relationships, but worked to create relationships and communities. We might take inspiration from scholarship on ancient written correspondence, in that “letters inscribe within themselves the identity of the author (as she or he wishes to present it) and that of the recipient (again as the author chooses to shape it).”103 Graffiti, too, allowed individuals to craft particular personas (as seen in the previous section), and call specific types of readers into being.104 In the brothel, open-ended greetings may have turned readers and listeners into members of an affective community, and the graffito about town rivalries may have brought to the fore local affiliations. Perhaps most poignantly, readers and listeners of the death notices immediately became a community of witnesses and mourners.

A final comment on the brothel’s graffiti comes by way of a one-word graffito – a quotation from the beginning of the second book of Vergil’s Aeneid – inscribed under the window of the east wall of room f.105 This particular snippet might be interpreted as an ironic response to the cacophony of voices present in this heavily inscribed room, countering, in turn: contiquere, “They [all] fell silent” (CIL 4.2213).