Chapter 9 - Caroline Bergvall’s Drift

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 February 2024

Summary

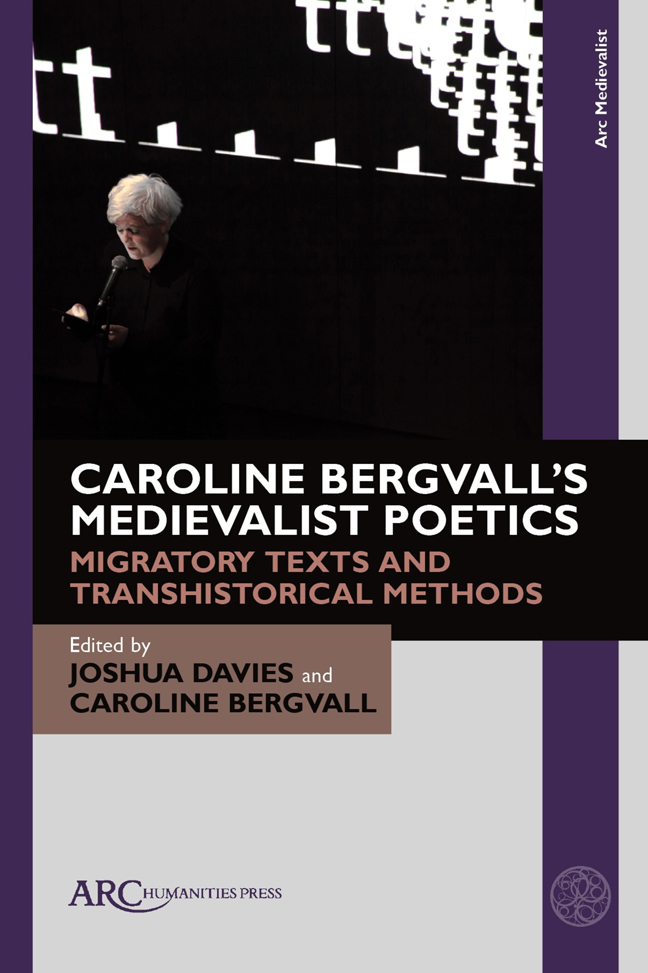

WHEN POET CAROLINE Bergvall first read reports of what became known as the “Left-to-Die Boat” in 2011, she had little idea this maritime tragedy would feature as the passionate core of a live performance and book project called Drift. She was translating a tenth-century, anonymous, Old English poem called The Seafarer but found that, when neither her native Norwegian nor modern English could source meaning, the word–roots and syllabic stems led to the rich, associative play and sonic experimentation of a new version. What starts as a pulsating invocation to sail north and beyond north, beyond peril, using the medieval “true tale” or “soþgiedd” as a template, becomes a multi-genre, elastic, athletic and magnificent sound poem, accompanied by the screen visuals of Swiss artist Thomas Köppel and live percussion by Norwegian musician Ingar Zach.

In an hour-long performance, Bergvall navigates the vastness, the lure, the connectivity and the dangers of the sea, moving through maritime chronology and topography with great intimacy and awe. She hacks into the Old English vaults, borrowing suffixes like “ge” and grafting them onto contemporary English, adapting, adopting, and ghosting words to create coupled meanings: “gewacked by / seachops gave up all parts of me on gebattered ship…hail hagl hard nothing else geheard gehurt but / sky butting sea.” Her neologistic verve is exuberant, enchanting and estranging. “Blow wind blow, anon am I” is whispered and droned as a tribute and a plea for change. Her allusive skaldic ballad sprays and spreads through history, evoking the women, like Gudrid Gudridur and Elizabeth Bowden, who cross-dressed to “scarper to sea” and the “hafville” (from the Viking “bewildered,” or “lost at sea”) artists who’ve guided Bergvall’s practice: from Li Bai and Rimbaud, to Jeff Buckley and Ingeborg Bachmann. Language eats itself as physical and/or spiritual fug sets in: “The f og was sodense that they l ost all s ense of dirrrtion.” The syllables shatter on the screen behind Bergvall, vowels sinking away as consonance emerges battered and bettered by the storm. “Show me the wave … Where will the wind come from?” Then the image slips and sways with multiple “t”s swimming in and out of view: “t” for interminable tossing and the “tick tick tick” of waiting for the fear of “sea fodder” and “gust ghosts” “sucking everything in” to pass.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Caroline Bergvall's Medievalist PoeticsMigratory Texts and Transhistorical Methods, pp. 81 - 82Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023