Book contents

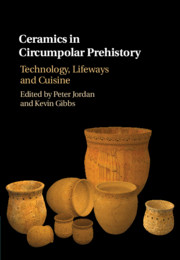

- Ceramics in Circumpolar Prehistory

- Ceramics in Circumpolar Prehistory

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- One Cold Winters, Hot Soups and Frozen Clay

- Two Why Did Northern Foragers Make Pottery?

- Three Vessels on the Vitim

- Four Maritime Nomads of the Baltic Sea

- Five The Paradox of Pottery in the Remote Kuril Islands

- Six Understanding the Function of Container Technologies in Prehistoric Southwest Alaska

- Seven Ethnographic and Archaeological Perspectives on the Use Life of Northwest Alaskan Pottery

- Eight An Exploration of Arctic Ceramic and Soapstone Cookware Technologies and Food Preparation Systems

- Nine Ceramic Use by Middle and Late Woodland Foragers of the Maritime Provinces

- Ten Prestige Foods and the Adoption of Pottery by Subarctic Foragers

- Eleven Use of Ceramic Technologies by Circumpolar Hunter-Gatherers

- Index

- References

Ten - Prestige Foods and the Adoption of Pottery by Subarctic Foragers

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 November 2018

- Ceramics in Circumpolar Prehistory

- Ceramics in Circumpolar Prehistory

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- One Cold Winters, Hot Soups and Frozen Clay

- Two Why Did Northern Foragers Make Pottery?

- Three Vessels on the Vitim

- Four Maritime Nomads of the Baltic Sea

- Five The Paradox of Pottery in the Remote Kuril Islands

- Six Understanding the Function of Container Technologies in Prehistoric Southwest Alaska

- Seven Ethnographic and Archaeological Perspectives on the Use Life of Northwest Alaskan Pottery

- Eight An Exploration of Arctic Ceramic and Soapstone Cookware Technologies and Food Preparation Systems

- Nine Ceramic Use by Middle and Late Woodland Foragers of the Maritime Provinces

- Ten Prestige Foods and the Adoption of Pottery by Subarctic Foragers

- Eleven Use of Ceramic Technologies by Circumpolar Hunter-Gatherers

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Ceramics in Circumpolar PrehistoryTechnology, Lifeways and Cuisine, pp. 193 - 215Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019