Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Contributors

- Introduction: Reimagining the Contemporary Musical in the Twenty-first Century

- PART ONE ORIGINAL MUSICALS

- PART TWO STAGE TO SCREEN

- 7 Star Quality? Song, Celebrity and the Jukebox Musical in Mamma Mia!

- 8 Beyond the Barricade: Adapting Les Misérables for the Cinema

- PART THREE MUSICALS BY ANOTHER NAME

- Index

8 - Beyond the Barricade: Adapting Les Misérables for the Cinema

from PART TWO - STAGE TO SCREEN

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 January 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Contributors

- Introduction: Reimagining the Contemporary Musical in the Twenty-first Century

- PART ONE ORIGINAL MUSICALS

- PART TWO STAGE TO SCREEN

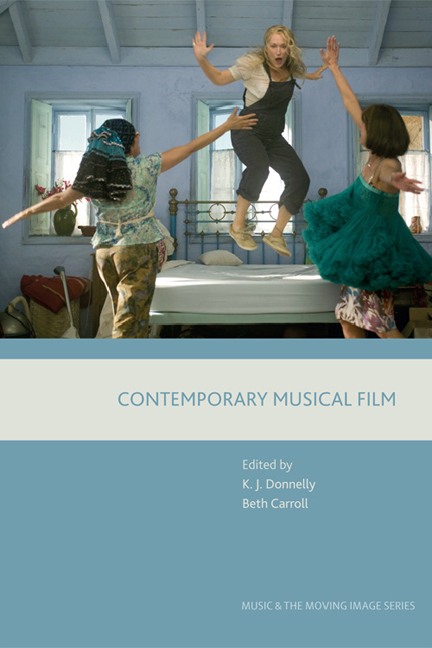

- 7 Star Quality? Song, Celebrity and the Jukebox Musical in Mamma Mia!

- 8 Beyond the Barricade: Adapting Les Misérables for the Cinema

- PART THREE MUSICALS BY ANOTHER NAME

- Index

Summary

Adaptations of Broadway shows were the mainstay of the film-musical genre at the height of its popularity in the 1950s and 1960s, with cinematic releases of Rodgers and Hammerstein's Oklahoma! (1955), Carousel (1956), The King and I (1956), South Pacific (1958) and The Sound of Music (1965), as well as other hits including Guys and Dolls (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1955), Anything Goes (Robert Lewis, 1956), West Side Story (Robert Wise, Jerome Robbins, 1961), Gypsy (Mervyn LeRoy, 1962) and The Music Man (Morton DaCosta, 1962). The popularity of the genre declined rapidly in the 1970s, but the release of Baz Luhrmann's Moulin Rouge in 2001 sparked something of a renaissance for the movie musical. However, there have been relatively few adaptations of stage musicals compared to made-for-screen offerings since the turn of the twenty-first century, and film adaptations of established shows no longer offer the sort of guarantee of success that they did fifty years ago.

Contemporary stage-to-screen adaptations have enjoyed mixed fortunes at the box office, with some, such as Chicago (Rob Marhsall, 2002), Hairspray (Adam Shankman, 2007) and, as Catherine Haworth discusses in her chapter in this volume, Mamma Mia! (Phyllida Lloyd, 2008), proving to be commercially successful. In these cases the films covered their production costs within a few weeks of opening in America and generated vast profits from screenings worldwide, but others have failed to match these returns despite being based on profitable and long-running Broadway properties. Rent (Chris Columbus, 2005) opened in cinemas while the show was still running at the Nederlander Theatre, but fell short of recouping its $40 million budget – indeed, the release of the film coincided with a surge in ticket sales for the stage show, perhaps indicating that audiences opted instead to see the musical in the theatre. The Producers (Susan Stroman, 2005) and Rock of Ages (Adam Shankman, 2012), the latter of which is considered elsewhere in this volume by K. J. Donnelly, fared similarly despite strong Broadway runs that were ongoing at the time the movies were released, demonstrating that translating Broadway longevity into Hollywood profitability is not always a simple task.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Contemporary Musical Film , pp. 123 - 140Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2017