8 - Śaiva Religious Iconography: Dancing Śiva in Multi-Polity Medieval Campā

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 September 2023

Summary

As early as the 5th century CE, Śaivism had risen to eminence on the Indian subcontinent as an established religious institution. Prosperous maritime trade routes between India and China brought Śaivism to the new lands of Southeast Asia, including Campā, a chain of small coastal polities that developed during the first millennium CE in present-day central and southern Vietnam. The name ‘Campapura’ first appeared in a local Cam inscription, the Mỹ Sơn Stele of Prakāśadharma (C. 96), which is dated to 658 CE. A few years later, in the Khmer Kdei Ang inscription (K. 53), the name ‘Campeśvara’ is mentioned as well (Coedès and Parmentier 1923: 46; Schweyer 2010). But Campā did not exist throughout its history under the same name, as it was referred to in several Chinese sources under different names such as Linyi 林邑 (Viet. Lâm Ấp) from 192 to 758, Huanwangguo 環王國 (Viet. Hoàn Vương quốc) from 758 to 886 and Zhancheng 占城 (Viet. Chiêm Thành) from 886–1471 (Vickery 2011: 369). In addition, if early French scholarship often described Campā as a unified kingdom, the last few decades have seen a wave of new studies concerning Campā not as a single entity, but as a multi-polity Cam ‘network state’ comprised of five regions or principalities located from North to South in present-day Vietnam: Indrapura, Amarāvatī, Vijaya, Kauthara, and Pāṇḍuraṅga. Keith Taylor (1999: 153) defined Campā as ‘a generic term for the polities organized by Austronesian-speaking peoples along what is now the central coast of Vietnam’, while Vickery (2011: 378) asserts that there was no single kingdom named ‘Campā’, and that the regions as distinguished in epigraphy corresponded to distinct geographical, and even rival, polities. This prompts the question as to what kind of political relationships and connections there existed between different parts/regions of Campā, and whether these regions can be conceptualized as polities, states, or principalities. There are of course differences between these terms but for the time being, as my chapter focuses more on artistic rather than political aspects, I will use these terms interchangeably. And for the sake of convenience, I will use the term Campā to include all Cam polities.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

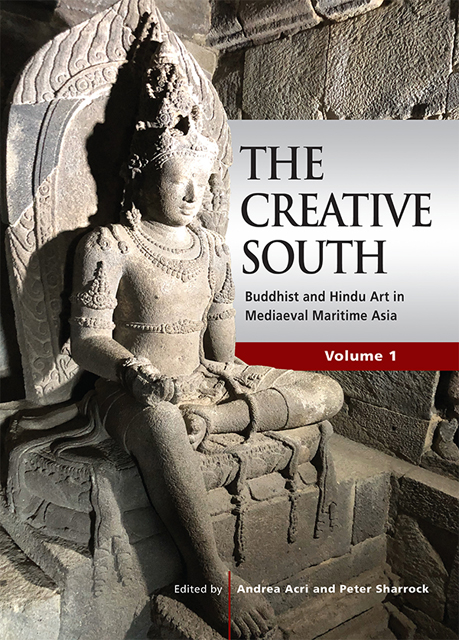

- The Creative SouthBuddhist and Hindu Art in Mediaeval Maritime Asia, pp. 289 - 304Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstituteFirst published in: 2023