Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Maps

- Introduction

- 1 The Role of Agriculture in Kenya’s Political Economy in the Era of Transition and Independence

- 2 Western Kenya’s Region, People, and the Origins of Population Density

- 3 Chavakali Secondary School: A Place of Learning and Farming

- 4 “Doing Their Part”: 4-K Farmers’ Clubs

- 5 Friends and Acres: The Friends Africa Mission Stewardship Program

- 6 “Home is Home”: The Lugari Settlement Scheme and Maragoliland

- Conclusion: Agricultural Production—The New (Old) Sexy

- Appendix: Interviewee Information

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

4 - “Doing Their Part”: 4-K Farmers’ Clubs

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 January 2023

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Maps

- Introduction

- 1 The Role of Agriculture in Kenya’s Political Economy in the Era of Transition and Independence

- 2 Western Kenya’s Region, People, and the Origins of Population Density

- 3 Chavakali Secondary School: A Place of Learning and Farming

- 4 “Doing Their Part”: 4-K Farmers’ Clubs

- 5 Friends and Acres: The Friends Africa Mission Stewardship Program

- 6 “Home is Home”: The Lugari Settlement Scheme and Maragoliland

- Conclusion: Agricultural Production—The New (Old) Sexy

- Appendix: Interviewee Information

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

“I couldn’t become a farmer … farming was dirty … I didn’t even want my own children to think of it … even my own father, I remember my own father, there were times when we joined together as young men and we would go and dig land and plant … if he [my father] found me, he would’ve told me ‘I took you to school, I didn’t take you to go dig for people,’ so, we were forced not to think [about farming] … so long as they [my parents] saw me reading my books that was enough.”

As a high school student in early 1960s rural western Kenya, Pierson Zavani understood very well what his privileged position meant for himself and his household. He knew, for instance, that his parents expected him to take schooling seriously by refraining from extracurricular activities that were distracting. Among other things, this translated to Zavani devoting his free time to his studies rather than to helping his parents (and neighbors) prepare their farms for the seasonal harvest while not in classes. He made his parents’ expectations clear in the above comments when he explained his choice to “stay off the land” upon completing high school. In short, Zavani was discouraged from “digging land” for anyone, including for his own parents who had a five-acre farmstead in Maragoliland, because he was a “learned” person.

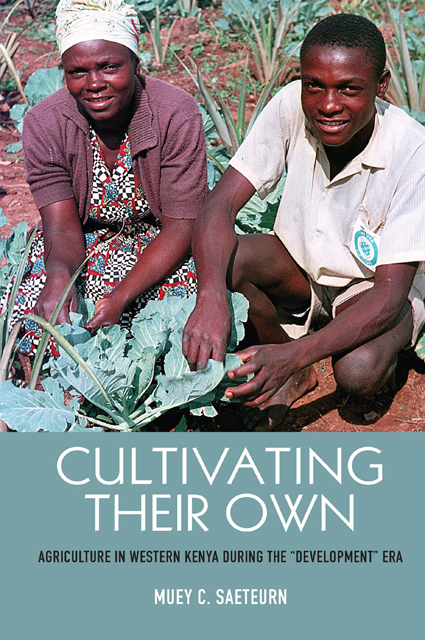

Despite his father’s objections, however, Zavani was an active 4-K club participant (4-K refers to Kuungana (to unite), Kufanya (to do), Kusaidia (to help), and Kenya) during a period when the Kenyan government and its development partners hoped to capture the imagination of rural people by way of its agrarian project, which championed the notion that prosperity was tied to working on the land. 4-K clubs specifically aimed to cultivate an interest in small-hold cash farming amongst the rural youth between the ages of ten and twenty-two years in regions like the Maragoli heartland in the North Nyanza district of western Kenya. This agricultural youth organization was popular in the early 1960s, especially with nationalist Kenyan leaders and their British counterparts and American advisers who recognized the importance of encouraging the younger generation residing in the countryside “to play their part in building the new African economy and society” by taking farming seriously.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Cultivating their OwnAgriculture in Western Kenya during the 'Development' Era, pp. 76 - 98Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2020