Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 What are psychoactive drugs, who uses them and why?

- 2 Drug use and adolescence

- 3 Having the drug conversation with your child

- 4 Drugs and the brain

- 5 Types of drugs

- 6 Rise of the synthetics

- 7 Detecting drug use and what to do about it

- 8 Treatment and recovery

- 9 Final thoughts

- Appendix

- References

- Index

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 What are psychoactive drugs, who uses them and why?

- 2 Drug use and adolescence

- 3 Having the drug conversation with your child

- 4 Drugs and the brain

- 5 Types of drugs

- 6 Rise of the synthetics

- 7 Detecting drug use and what to do about it

- 8 Treatment and recovery

- 9 Final thoughts

- Appendix

- References

- Index

Summary

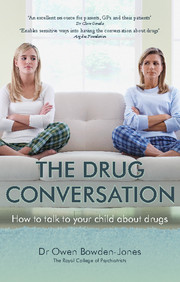

‘Mind your own business. What I do is up to me. You always go on about drugs being bad, but what do you know? You told me you've never taken any, right? So how do you know what's what? You don't know anything!’ – a 15-year-old's response to being asked by his mother if he is taking drugs.

I'm sitting with Harry, a bright, articulate 15-year-old who attends a well-known school in London. Harry's parents are here too, looking anxious and frustrated. This is my second meeting with Harry and he is here because he uses drugs. He mostly uses cannabis but also occasionally ecstasy and, on one occasion, he has taken cocaine. To Harry's dismay, one of his friends told a teacher that they were worried about him. The head teacher called Harry and his parents to a meeting to discuss his progress and reported drug use.

Harry doesn't think his drug use is a problem, claiming that all of his friends smoke a joint (of cannabis) ‘now and then’ and that he uses less than some. Despite recently falling grades, Harry knows he is bright and wants to go to university to study journalism, something he has wanted to do for as long as he can remember. He seems relaxed, even confident, as he talks to me about how cannabis helps control his anxiety, improves his sleep and makes him feel relaxed and ‘part of the crowd’. He can't imagine a life without drugs.

Harry's parents, on the other hand, are horrified. They can hardly bring themselves to believe that Harry is using drugs and blame his friends for introducing him to them. They think he has fallen in with a ‘bad lot’ and is putting his promising future at risk. At today's meeting, they ask Harry to stop using drugs immediately, threaten to ban him from seeing his friends and insist that he is drug-tested every week. They become frustrated and angry when he says that they are overreacting and accuses them of being out of touch and ignorant about drugs.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Drug Conversation , pp. 1 - 4Publisher: Royal College of PsychiatristsPrint publication year: 2016