Book contents

Epilogue: He Who is Made Lord

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2024

Summary

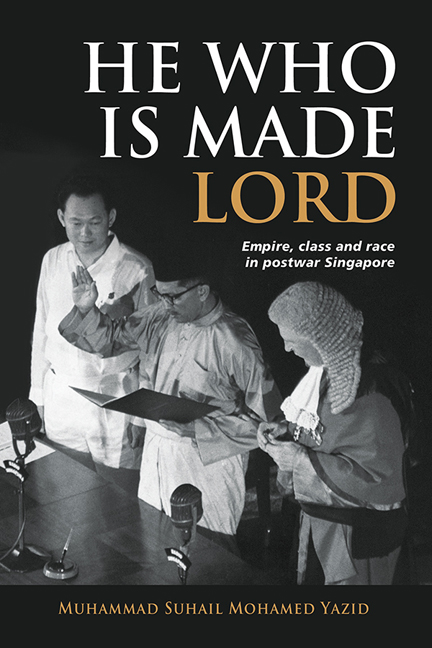

On 3 December 1959, the recently elected government of Singapore successfully installed Yusof bin Ishak as the first Malayan-born Yang di-Pertuan Negara. After over a century of British colonialism and a brief interlude of Japanese rule, the island state entered a new era of self-government, even as it waited for an uncertain reunion with the Federation of Malaya. The gaudy rhetoric, visuals and styles that accompanied the representative of the British Crown produced an atmosphere of a nationalist revolution, a rupture from the colonial order. Singapore was on the precipice of the new and unknown, a threshold of change and transformation. The talismanic vigour of the Yang di-Pertuan Negara represented a “Malayan” nation emerging from the obsolete era of imperial domination.

But underneath the grand parading of national sovereignty, Singapore was still in limbo. The island remained trapped in a colonial purgatory, in a liminal zone where states were denied sovereign equality and kept in an imperial system under the enduring dominion of Britain. In this “new” Singapore, the Yang di-Pertuan Negara was also exalted as a symbol of social equality, and yet, the office generated a series of secret plots, surreptitious plans and public performances which revitalized the stratifying practices of class distinctions in colonial society—a few continued to be more equal than others. With the coming of the

Malayan-born Yang di-Pertuan Negara, there was also a concurrent push towards the breaking down of the racial divisions entrenched during colonial rule. The office not only signified the erosion of the “Whites only” colour bar, but also served as a catalyst for a transcendental sense of “Malayan” identity between Singapore's different racial groups. The lumpiness of interracial relations, however, continued to taunt symbolic meanings of the Yang di-Pertuan Negara. Underneath the bold gesture of appointing a person of colour to the highest office in the land, uneasy contradictions persisted. Material disparities between different racial groups continued to threaten the promise of a post-racial and more equal social order.

An idealist among the PAP leaders, Minister S. Rajaratnam devolved the meaning of being “Malayan” to “the artists, the dramatists and the painters”. The same could be said for the multiple meanings of the Yang di-Pertuan Negara, the embodied representation of the “Malayan” nation in Singapore: the “artists”

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- He Who Is Made LordEmpire, Class and Race in Postwar Singapore, pp. 209 - 216Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2023