Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements and Permissions

- Foreword

- Introduction: Writing South Africa's Yawning Void

- Part I Coming into Writing

- Part II Writing about Pressing Issues

- Part III Writing about My Writing

- Conclusion: A Tribute to Those Who Came Before Me

- Notes

- Selected works

- Bibliography

- Index

6 - Do Not Choose Poverty

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 March 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements and Permissions

- Foreword

- Introduction: Writing South Africa's Yawning Void

- Part I Coming into Writing

- Part II Writing about Pressing Issues

- Part III Writing about My Writing

- Conclusion: A Tribute to Those Who Came Before Me

- Notes

- Selected works

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

This essay spells out in detail the personal story that Sindiwe Magona references again and again in her writing: her dramatic escape from the extreme poverty she was born into as a black South African woman in 1943. She leans heavily upon this origins narrative not to castigate those in unfortunate circumstances but to inspire them to reject the assumption that the poor inherently lack the agency to improve their lives.

MANY OF THE world's poor are born into poverty. Some escape, many do not. Tragically, many do not only not escape poverty but actually sink deeper and deeper into the quagmire. However, most, if not all, have a fighting chance to escape poverty. Take it from me, you can escape poverty. I know, because I did.

I was born poor. That is true of most people my age group, born black in apartheid South Africa or before. Black-black1 Africans were not recognised as citizens of South Africa, their birth country. Apartheid South Africa was governed by white people, governed with the sole purpose of legally barring all those not white-skinned from meaningfully participating in the economy of the country – the darker, the further the push away from being a person who experienced a life worth living. Yes, even oppression apartheid implemented according to rank: white best; coloured next; black crushed to the ground. Black-black people didn't even have identity numbers. An ID number means you are counted as a human being, a member of a society, with a numerical value in the census. Black Africans were not counted – not as South Africans. Which is why describing the pass or dompas as an identity document, as some are wont to do, is incorrect. The pass book was a reference book in that it provided a number in reference to a black body being in a certain geographical or urban area, legally, for the purpose of residence (if that body qualified for this ‘right’), and/or the employment of a black body by such and such – this last, always and only a white body or organisation comprising a group of white bodies. Residence and employment, the first to serve the second, were the two criteria. Visits, as for a funeral or wedding, were of very short duration – never more than three weeks; vacation from work, normally a month (minus travel time, three weeks) is all one was permitted.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

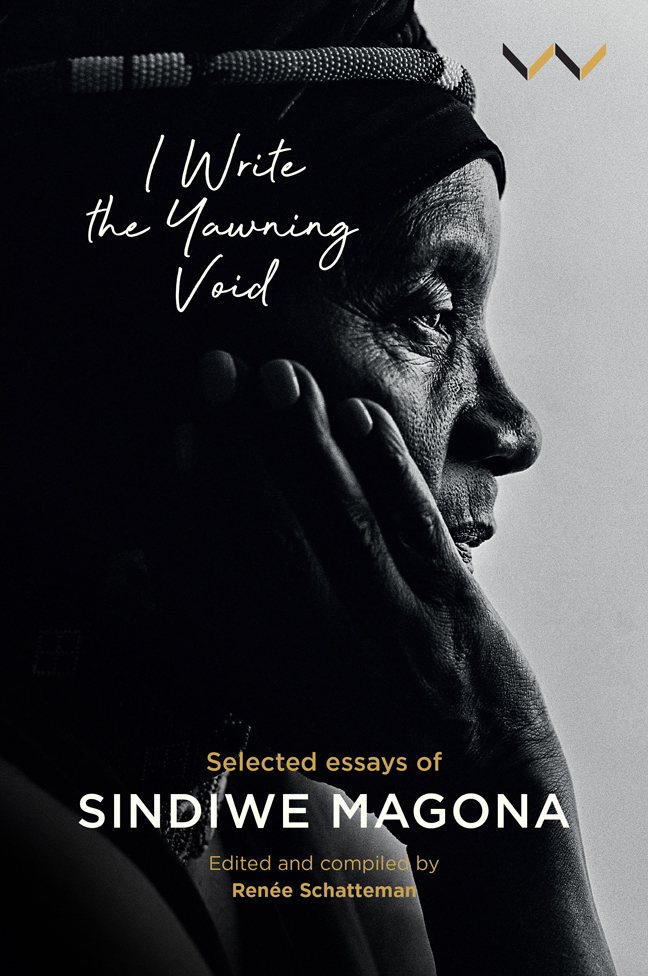

- I Write the Yawning VoidSelected Essays of Sindiwe Magona, pp. 61 - 73Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2023