Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- A Note on Translations

- Bibliographic Abbreviations

- Introduction: The Idea of Art Music in a Commercial World

- PART I PUBLISHERS

- PART II PERSONALITIES

- PART III INSTRUMENTS

- PART IV REPERTOIRES

- PART V SETTINGS

- Index

- Music in Society and Culture

11 - Schicht, Hauptmann, Mendelssohn and the Consumption of Sacred Music in Leipzig

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 May 2021

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- A Note on Translations

- Bibliographic Abbreviations

- Introduction: The Idea of Art Music in a Commercial World

- PART I PUBLISHERS

- PART II PERSONALITIES

- PART III INSTRUMENTS

- PART IV REPERTOIRES

- PART V SETTINGS

- Index

- Music in Society and Culture

Summary

IN autumn 1778, Johann Adam Hiller, music director (Kapellmeister) of Leipzig's leading subscription concert series since 1763, published a booklet to accompany the forthcoming Concerts Spirituels – the biannual set of sacred music programmes performed during the penitential seasons of Advent and Lent – that were to be presented by his Musikübende Gesellschaft (Music- Practising Society). The booklet is part of a very small group of documents that describe the city's public, commercial concert programming before the construction of the Gewandhaus concert hall and the founding of the Gewandhauskonzerte (Gewandhaus Concerts) in 1781. What makes it stand out, however, is Hiller's introductory essay on the texts of the works to be performed – mostly traditional Latin liturgical texts such as the mass ordinarium, Magnificat and Te Deum – in which he reflected on the role of sacred music in the concert season. These remarks were structured around an exegesis of the Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca's twenty-third epistle to Lucilius, in which he comments, ‘res severa est verum gaudium’ (‘a serious thing is a true joy’). Hiller printed the maxim on the cover of the booklet and used a slight variant (‘Res severa verum gaudium’; ‘Serious thing – True joy’) as the motto for the Gewandhaus, one that was emblazoned over its stage immediately after the hall's construction and has appeared in eponymous halls ever since.

Although Hiller's booklet is recognized as the moment this adage first became associated with the Gewandhaus, less notice has been taken of Hiller's essay itself, and particularly of Hiller's choice to discuss Seneca's words in connection to sacred, rather than secular, music. And while a spectator in the Gewandhaus might interpret the motto as a declaration that the music performed in the space is – and should be – something more than mere entertainment, Hiller's original intent was more closely related to sacred music's role in public concert life:

True joy is a very serious matter, says Seneca. The conviction of the truth of this statement, and the confidence in the right-thinking of our Leipzig residents, who exceed [those of] so many German cities in their love of music, have called for the newly established Musikübende Gesellschaft to perform so-called Concerts Spirituels during Advent and Lent, in which not only serious operas and oratorios would be performed, but also other large pieces of sacred music.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

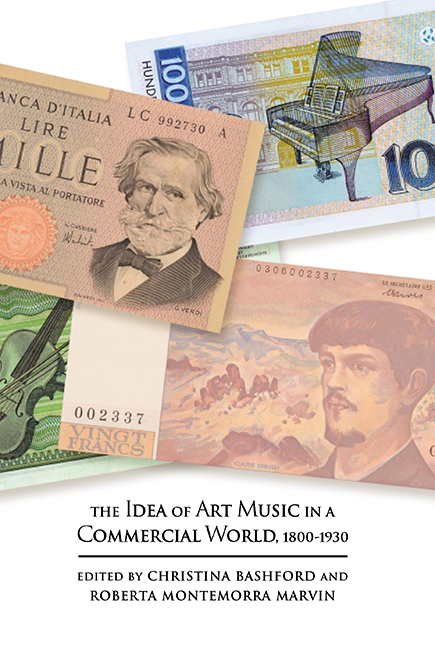

- The Idea of Art Music in a Commercial World, 1800-1930 , pp. 250 - 273Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2016