I Disaster Protection vs Free Movement

Not all disasters strike out of the blue. Some disasters develop over a long time – sometimes over several years. This allows societies to adopt measures to ward off – or at least reduce – the onslaught. Indeed, if a society can predict a future disaster with any reasonable certainty, most would probably agree that the authorities must be under a duty to adopt measures to ward it off.

Perhaps climate change is the best example of a slow-onset disaster: science is able not only to establish that climate change takes place but also to point out its likely consequences. Thus, we do not know precisely where and when climate change will manifest itself, but in practice there is consensus that the world will experience more severe hurricanes and heatwaves, increased wildfires, more prolonged droughts, rising sea levels, etc.Footnote 1 In other words, we have fairly clear and convincing predictions about what is in store for us – and for our children. The development of a number of diseases is also likely to be a slow-onset disaster. For example, we are witnessing an increased spread of multi-resistant pathogenic bacteria, i.e. bacteria that have become resistant to antibiotics. If we are unable to address this challenge, in the future we may expect to see people dying from infections that today we consider minor and easy to treat.Footnote 2

Thus, it is clear that we are faced with a number of predictable disasters – and it therefore seems only natural and well founded that we seek to protect ourselves against these threats. Where the authorities of a Member State introduce measures aimed at protecting that state against these predictable, future disasters there might well be instances where the measures, actually or potentially, directly or indirectly are capable of hindering the free movement of goods and/or services within the European Union – giving rise to the question whether the measures are lawful under EU law. This schism between the protection against slow-onset disasters and the EU’s free movement rules is the focal point of the present contribution in honour of Professor Laurence Gormley.

Three observations must be made before we embark upon our examination. First, we presuppose that the Member State measures constitute a barrier to trade covered by the provisions on free movement (goods and services)Footnote 3 laid down in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). It follows that we set out to clarify when a Member State measure is lawful irrespective of the fact that it impedes trade between Member States. Second, we presuppose that no secondary EU regulation applies in the field in question having the same objective as the one pursued by the Member State measure.Footnote 4 Third, we only consider ‘future disasters’ – meaning that, by definition, there will always be some uncertainty as to whether the disaster actually occurs – and if so how (i.e. when and with what consequences).

In what follows we first turn to consider the notion of ‘risk’ in an EU law context (section II). Next, we discuss how Member States may justify introducing measures against slow-onset disasters (section III). We thereupon consider how the (scientific) certainty and specificity regarding the different manifestations of the slow-onset disasters impact upon the legal assessment (section IV). We also discuss the situation where a Member State adopts measures addressing disasters occurring outside the Member State’s own territory (section V). Finally, we sum up our findings (section VI).

II Risk and EU Law

Before considering how to approach slow-onset disasters today, it may be useful to take a small step back in time; back to the 1980s when first of all the late Ulrich Beck published his seminal work Risikogesellschaft. Auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne (English title: Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity).Footnote 5 In this work Beck argued that the world was witnessing a new and systematic way of dealing with hazards and insecurities that were induced and introduced by modernisation itself. For our purposes, what is essential to keep in mind with regard to this ‘risk approach’ is, first, that in modern society human agency has come to play a central role both as an important cause of these risks and with regard to mitigating them.Footnote 6 And, second, that contemporary natural sciences play a key role in this context both because to a considerable extent ‘modern risks’ may be traced back to innovations based on the natural sciences, and because we need the natural sciences to identify the risk as such, to predict the consequences of the risk where it materialises, to estimate the likelihood that it materialises and to find ways of countering it.

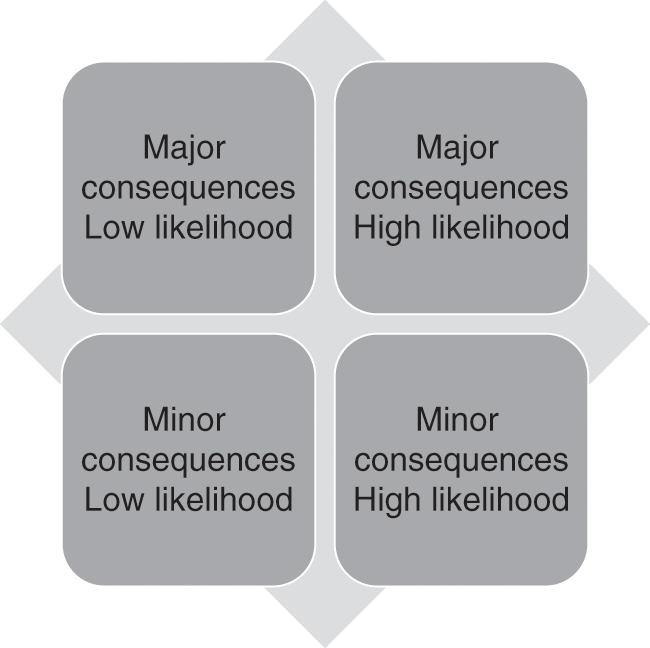

Below we will attach particular importance to two aspects inherent in slow-onset disasters, namely (1) the likelihood that the risk materialises and (2) the consequences it produces if it materialises.

Unsurprisingly, we must clearly distinguish the situation where there is a high likelihood that a risk will materialise producing major (adverse) consequences from the situation where there is a low likelihood that a risk will materialise – and that this will only have minor consequences.

Figure 34.1 The four categories of slow-onset disasters

Taking a risk approach is in no way alien to EU lawyers. Indeed, such an approach often forms an integral part of the EU legislative process. For example, if the authorities set out to regulate the use of a food additive, they may ask the producer of the additive to provide verifiable scientific data about the likely positive and negative effects of using the additive as well as the likelihood that the different negative effects will materialise. The legislator must also determine what risk level they consider acceptable – and they may draft the legislation accordingly. Similarly, we find the risk approach reflected in the proportionality principle as developed under EU law; thus, the authorities have a wider array of measures to choose between when they want to protect society against a risk that is likely to materialise and which will produce very adverse consequences as compared to a risk that is less likely to materialise and which will produce less adverse consequences if, nevertheless, it does materialise.

III Justifying Measures Addressing Slow-Onset Disasters

Any EU lawyer will know that where an EU Member State introduces measures that, directly or indirectly, actually or potentially, are capable of hindering intra-EU trade, this constitutes a Treaty infringement unless the measure pursues a legitimate objective and is proportionate. The Treaty itself lists some particularly weighty objectives that may justify the introduction of measures that constitute restrictions or are indirectly discriminatory or (in principle) even directly discriminatory.Footnote 7 Moreover, the Court of Justice of the European Union has established that measures that restrict intra-EU trade without being directly discriminatory can be lawful if they pursue so-called ‘mandatory requirements’Footnote 8 and are proportionate.

Slow-onset disasters may manifest themselves in many different ways. Still, where Member States adopt measures to prevent the disasters from materialising, in practice they are likely to only pursue a rather narrow range of objectives. Thus, a disaster will normally imply a risk to the health and life of humans, animals or plants, a risk to property and infrastructure and a risk to the environment more broadly. Moreover, there may be situations where a Member State fears that a disaster will affect public policy or public security – although these situations are likely to be less common. Measures introduced to ward off such risks are, as a clear rule, justifiable.Footnote 9

In other words, where a Member State adopts measures to prevent the negative impact of a slow-onset disaster while at the same time restricting trade between the Member States, it seems rather unlikely that the measures will not be found to pursue some legitimate interests under EU law.Footnote 10

IV Predicting and Countering Slow-Onset Disasters: Certainty and Specificity

A key characteristic of slow-onset disasters is that they develop over time, thereby allowing us to foresee them – at least to some extent. For example, drought is a classic slow-onset disaster that often develops over a long period of time. Adopting measures to address this type of slow-onset disaster does not differ from other Member State measures; thus, if the measure pursues a legitimate interest in a non-discriminatory way and if it is proportionate with this objective, it will be lawful under EU law.Footnote 11

The above concerns situations where it is possible to foresee the slow-onset disaster with a high degree of certainty meaning that scientific data permit a full evaluation of the inherent risk. However, not all slow-onset disasters can be foreseen with any appreciable degree of certainty. For example, considerable efforts are put into predicting the consequences of climate change, but still there are appreciable uncertainties associated with these predictions. And the further we look into the future, the more uncertain and imprecise are the predictions.

In other words, we are faced with a situation where, on the basis of ‘the most reliable scientific data available and the most recent results of international research’,Footnote 12 it is possible to identify specific climate change-induced phenomena that may pose serious threats to human societies – such as more powerful and more frequent hurricanes or more frequent and more prolonged water shortages – identified by a scientific and objective evaluation, but where it is impossible to determine with certainty the existence or extent of the alleged risk because of the insufficiency, inconclusiveness or imprecision of the results of studies conducted.Footnote 13 In this situation, under EU law, we must revert to the precautionary principle.Footnote 14

Thus, the precautionary principle applies to cases where scientific evidence is insufficient, inconclusive or uncertain and where a preliminary scientific evaluation indicates that there are reasonable grounds for concern that the potentially dangerous effects on the environment or on human, animal or plant health may be inconsistent with the desired level of protection that has been laid down by the authorities. Where the authorities can establish that such situation exists, under the precautionary principle they may adopt measures aimed at providing protection against this presumed risk in order to ensure the level of protection laid down by the authorities.Footnote 15 These measures may be in force pending further scientific information that allows for a more comprehensive risk assessment, they must be proportionate and they may not be more restrictive of trade than what is required to achieve the level of protection laid down by the authorities.Footnote 16 Moreover, it is incumbent on the authorities to regularly review the measures in order to ensure that they continue to be justifiable.

When establishing whether a given measure, adopted on the basis of the precautionary principle, is proportionate we must take into account not only (1) the likelihood that the risk materialises and (2) the consequences it produces if it materialises, but also (3) the certainty with which we can establish the likelihood and the consequences. In other words, if our scientific data with a very high degree of certainty show that there is a high likelihood that climate change will cause some adverse consequences the authorities will have a strong basis for adopting measures targeting these consequences even if the consequences are not particularly far-reaching. In contrast, if scientific data indicate that there is a high likelihood that some very adverse consequences will materialise sometime in the future, but these data involve a high level of uncertainty, the authorities have a much weaker basis for adopting the measures.

In the opinion of the present author, the precautionary principle in combination with the principle of proportionality, as first of all developed in the case law of the European Court of Justice, provide a sound legal framework for when and how Member States may (or may not) introduce measures addressing slow-onset disasters. Still, as convincingly pointed out by Cass Sunstein in Laws of Fear,Footnote 17 whereas the European Union’s approach to the precautionary principleFootnote 18 provides a plausible start, it nevertheless leaves many open questions as well as a number of doubts.Footnote 19

V Member State Pursuing (Legitimate) Interests beyond Its Own Territory

Slow-onset disasters do not recognise borders. Thus, multi-resistant pathogenic bacteria may travel from one continent to another – in a very short time. And climate change may manifest itself in many different ways and places. That slow-onset disasters are a matter for the international society is reflected in a number of international agreements. For example, in 2015 WHO, the UN World Health Organization, laid down a Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance,Footnote 20 also in 2015, 196 parties entered into the Paris Climate Agreement,Footnote 21 and in the same year the so-called Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted by the UN Member States and global civil society actors.Footnote 22 Many more international arrangements exist where the participating parties undertake to cooperate in order to address what essentially are slow-onset disasters.

The EU Member States and/or the European Union take a very active part both in the international legislative work and in the ensuing arrangements. These activities only very rarely give rise to questions regarding possible infringements of the Treaty rules on free movement, but nevertheless it may still be useful to briefly examine this possible conflict. To this end, we shall distinguish between, on the one hand, situations where a Member State adopts measures aimed at promoting its own interests, and, on the other hand, situations where the measure is intended to promote the interests of the state where the slow-onset disaster takes place. Let us illustrate this through an example where a slow-onset disaster begins to materialise.

VI Example

In Iceland a contagious and deadly bacteria slowly starts to spread. The bacteria is resistant to all but one type of antibiotics – and if at some point it turns into an epidemic, it is feared that we will have a new ‘Spanish flu epidemic’. In order to protect its citizens against this danger, Member State A prohibits all air carriers that continue to service Iceland from servicing Member State A airports.

Member State A’s measure may be contrasted with that of Member State B. Thus, Member State B prohibits all Member State B holders of the only type of antibiotics that is known to defeat the bacteria from selling (including exporting) any part of their stock. Instead they are required to surrender their full stock at cost price to Member State B in order that this antibiotic may be sent to Iceland.

Member State A’s measure excludes air carriers in other Member States from servicing Member State A, and Member State B’s measure prevents the holders of a specific antibiotic from exporting their stock of this antibiotic to other Member States.Footnote 23 Both measures therefore constitute a trade restriction as defined in the European Court of Justice’s Dassonville ruling (capable of directly or indirectly, actually or potentially hindering trade).Footnote 24 But whereas the measure adopted by Member State A is intended to protect the interests of this Member State, the measure adopted by Member State B is first of all adopted in the interest of Iceland.

In either of the two situations the state on whose territory a slow-onset disaster manifests itself must (as a rule) be considered to be the principal responsible for addressing the disaster. Therefore, in order to introduce a measure that is capable of restricting intra-EU trade and which suitably addresses slow-onset disasters that occur outside the Member State in question, the Member State must demonstrate that the measure is ‘necessary’.Footnote 25 If the slow-onset disaster takes place outside the Member State’s own territory, but may be expected to produce adverse effects within the Member State’s territory, this will be very similar to the situation where the slow-onset disaster manifests itself directly within the Member State.Footnote 26 Thus, whether a slow-onset disaster directly or indirectly produces adverse consequences within the territory of a Member State should not have any bearing on the legality assessment of any measures adopted to counter the slow-onset disaster.Footnote 27

The situation is rather different where a Member State adopts measures that are capable of restricting intra-EU trade in order to protect interests exclusively outside its own territory. If these interests are found in another EU Member State and if the measures are not supported by this other Member State, it seems to be very difficult to establish an argument that the measures are necessary (and lawful).Footnote 28 In contrast, if the measures are introduced with the acceptance of this other Member State (perhaps even at its instigation) the measures may be presumed lawful (presupposing that they are proportionate and comply with the principle of proportionality).

The situation is likely to be the same where an EU Member State adopts measures addressing slow-onset disasters in third countries, unless the third country is incapable of or unwilling to protect its own citizens (etc.) against slow-onset disasters. For example, during the Arab Spring, governments in several Middle Eastern and North African states were paralysed while at the same time the countries suffered from widespread droughts. In this situation assistance from EU Member States would seem warranted.

Moreover, under international public law – for example the Paris Climate Agreement – Member States may be under a legal obligation to provide assistance to third countries. If a Member State, in full conformity with EU law, has assumed a legal obligation to provide assistance to a third country and if such assistance can only be provided in a way that is capable of hindering intra-EU trade, we may expect the European Court of Justice to accept this.Footnote 29 Admittedly, it is rather difficult to imagine such situation in practice.

VII Conclusions

In this contribution we have first seen that applying a risk approach has become an integral part of EU law. Slow-onset disasters really are about risks – and may manifest themselves in many different ways. Such manifestations are particularly likely to pose a risk to the health and life of humans, animals or plants, a risk to property and infrastructure and a risk to the environment more broadly. Proportionate Member State measures introduced to ward off such risks are, as a clear rule, justifiable. We have also found that the precautionary principle in combination with the principle of proportionality provide a sound framework for the lawful introduction of measures addressing slow-onset disasters – while acknowledging that the European Union’s construction of the precautionary principle leaves many open questions as well as a number of doubts. Turning to the question of how a Member State may address slow-onset disasters that take place outside the Member State’s own territory, we find that there is no reason to distinguish situations where a slow-onset disaster may be expected to produce adverse effects directly within the territory of the Member State as compared to the situation where it only indirectly produces such (appreciable) effects. Somewhat more hesitantly, we also find that a Member State may adopt measures addressing slow-onset disasters that are unlikely to produce effects in the Member State’s own territory provided that the measures are supported by the state where the effects will occur. We also find that, exceptionally, such measures may be lawfully adopted even where the state where the slow-onset disaster occurs does not support (or even opposes) the measures. Finally, we consider to what extent a Member State may invoke public international law in support of the introduction of measures that are aimed at slow-onset disasters beyond that Member State’s territory. We find that in theory it may be possible to make such legal argument, but we also find that in practice it is difficult to imagine a situation where this will be relevant.