Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Images

- An Introduction

- 1 Wound: On Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

- 2 Touch: On Giovanni Lanfranco’s Saint Peter Healing Saint Agatha

- 3 Skin: On Jusepe de Ribera’s Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

- 4 Flesh: On Georges de La Tour’s Penitent Saint Jerome

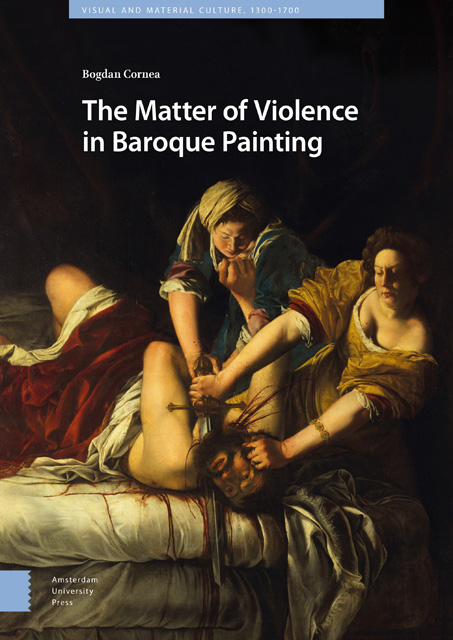

- 5 Blood: On Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

- 6 Death: On Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion

- Conclusion

- General Bibliography

- Index

6 - Death: On Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 April 2023

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Images

- An Introduction

- 1 Wound: On Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

- 2 Touch: On Giovanni Lanfranco’s Saint Peter Healing Saint Agatha

- 3 Skin: On Jusepe de Ribera’s Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

- 4 Flesh: On Georges de La Tour’s Penitent Saint Jerome

- 5 Blood: On Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

- 6 Death: On Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion

- Conclusion

- General Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Abstract

Chapter Six explores the relationship between corporeal fragmentation and darkness in Francisco de Zurbaran’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion. The chapter argues that the painting’s modulation of white and dark produces a form of violence that is simultaneously concealed and revealed in the dazzling succession of deep folds. This implies an interpretation where the white garment, instead of hiding away the martyred body, become a visual vehicle for its violence; namely, its deep and heavy folds establish an analogous relationship with the fragmentation of the saint’s body. The folding of the body is replicated in the folding of light and dark on the surface of the painting – a material and temporal process that has the potential to transform the pictorial surface into a tomb.

Keywords: Zurbaran, corporeality, fragmentation, folds, tomb, death

St. Serapion, I wrap myself in the robes of your whiteness which is like midnight in Dostoevsky.

– Frank O’HaraObserve: there is no blood, no wound, no instrument of torture or execution, nothing to betray the presence of any sign of physical violence. The friar’s white habit is spotlessly clean. The man looks calm, almost asleep. Surely, there is no violence to be seen in this painting for there is none shown outwardly. And yet, we see the head sunken, the body hanging low. His hands are tied with ropes to some kind of wooden frame barely discernable in the background. Perhaps he has been knocked out, has fainted, or is exhausted – or is he dead? One cannot really say. The thick bonds hold his limp body frontally to the painting’s frontal view; he is presented to us, exposed, displayed, strung up, and put on show. We are confronted with a figure stretched out on the canvas’s stretcher, extracted from the dark ground, wrapped in a succession of white folds, deep and heavy, broken and fragmented, like the saint’s martyred body.

From within the folds a paradox arises: How is it possible to convey the violence of martyrdom without showing any signs of bloodshed and suffering, to render a torn body without depicting ripped flesh and skin, or to make death an absent presence?

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Matter of Violence in Baroque Painting , pp. 141 - 160Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023