When Kaleem Caire arrived back to his hometown of Madison, Wisc., in 2010 after working for President Obama on the Race to the Top education plan, he found a community little changed from the one he’d left years prior – at least in terms of the opportunities available to people of color.Footnote 1 He, his wife, and his five children – two girls and three boys – were African American. Yet, there in that midsized, college-dominated city, the achievement disparities between White, Black, and Brown people were some of the worst in the United States. African American and Latino students trailed their White counterparts at all education levels in areas such as reading test scores. One in every two Black males in Madison were failing to graduate high school in four years – compared to a graduation rate of 88 percent for their White counterparts. The situation seemed to get worse every year as more and more African Americans, Hispanics and other minorities enrolled in the local schools; minority groups comprised a majority of the Madison schools’ population. The thought of raising his kids in that environment dismayed the new head of the Urban League of Greater Madison and he was ready to effect change in a real way. While he was away, people had been working on the problem; committees had been formed, reports had been written. But political stalemate, financial uncertainty, inertia, and an unwillingness to redirect resources away from other student groups for 20 percent of the student population stymied any major solutions from being implemented. Caire rolled up his sleeves and set to work.

In September 2011, Kaleem Caire won a planning grant to develop a publicly funded charter school called Madison Preparatory Academy that would educate Black and Latino boys in grades 6–12. After much research, Caire had landed on what he considered to be the best alternative to the public schools. Madison Prep was modeled after Chicago Preparatory Academy and a variety of other charter schools across the country that seemed to be meeting the needs of Black children where public schools were failing. His first proposal (which changed several times over the year) at first excluded girls in order to focus on Wisconsin’s Black boys, who ended up in prison more frequently than in any other state. The students would wear uniforms, attend school for longer hours, and participate in summer learning activities. It would cost the district an additional $4 million over the course of five years.Footnote 2 It wasn’t perfect, but Caire thought it was a stab at something, an experiment in a place that seemed to him to be badly in need of new ideas.

Caire needed the approval of the 2011 Madison Metropolitan School District’s seven-member Board of Education (BOE), made up of White, older progressives with the exception of one Black male. The BOE represented Madison voters (mostly White), not Madison kids (now a majority minority) and had historically had strong connections to the local teachers’ union. He also knew he needed the community of Madison behind him. The capital city of nearly 250,000 skewed liberal – indeed, it liked to brag about itself as the birthplace of the Progressive Party. Madison regularly appeared on “Best City” lists for its friendly community, livable environment, world-class education, bike paths, dog parks, and many other metrics. Its White citizens imagined themselves to be community oriented, volunteered in their kids’ schools, and donated to charity. If White people did not encounter many people of color during their commute to the university or their law office at the Capitol, they enjoyed hearing several languages spoken and many considered themselves color-blind. And these White residents were well off, with an average household income of $61,000 and ranked as having the highest concentration of PhDs in the country.

Yet Madison, like many places in the world, harbored implicit biases and enacted institutionally racist policies. Cops picked up Black teens at a rate six times that of White teens. Employers passed over Black applicants such that the unemployment rate for Black people was 25.2 percent compared to just 4.8 percent for White people in 2011. Even the schools were disciplining Black children more harshly and frequently than the White kids, with a suspension ratio of 15 to 1.Footnote 3 And though many White people in town would bristle at the idea that such an intellectually progressive place could harbor such racial problems, the Black people I talked to for this book – without exception – described a segregated city where hostile environments were the norm for people of color.Footnote 4 Caire knew he had an uphill battle, not only in behind-the-scenes negotiating with school officials, but also in the public realm. He knew he’d encounter resistance and suspicion and defensiveness: He just wanted people to “stay in the room” to hear him out.

The proposal immediately generated controversy and a raging public debate ensued – borne out in local news outlets, education blogs, Facebook, and other social media. The Urban League of Greater Madison appealed for public support in YouTube videos, showing charts filled with achievement gap metrics. Local activists debated it in popular blogs with one linking to dozens of reports full of research evidence. Reporters covering the proposal wrote articles full of meeting logistics and he-said/she-said “evidence.” Hundreds of Madison citizens commented on Facebook posts and news articles, railing against Madison Prep or persuading BOE members to give the charter school a try, relaying personal stories, quoting experts, or citing blog posts. Caire spent much of his time posting upcoming hearings or newly released reports on charter schools on his Facebook page, emailing out messages that were picked up by blogs or local media, and answering phone calls from reporters.

On one level this book documents the story of Caire, Madison Prep, and the aftermath as it unfolded in the public sphere. As a White, liberal professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison as this narrative took shape, I had a front row seat to the onslaught of vitriolic commentary and stilted debate that occurred in the news media, on Facebook, on Twitter, and in the blogosphere. I read all of Caire’s public Facebook, Twitter, and blog posts and the intense discussions that followed. I watched the hearings where parent after parent talked about the marginalization of their children in the school systems and then I saw these same parents’ experiences discounted by other speakers. I noted the meeting-driven, he-said/she-said coverage in the local media. And overall, I became intrigued at the ineffective communicative patterns I saw, especially how important voices in the discussion about the achievement gap were ignored, suppressed, or completely absent. I began documenting how community information circulated on the issue via different media – social, traditional, and other. I was particularly interested in the quality of the material that was flowing so quickly, so voluminously, and wondered: how can public content about significant racial issues reflect inclusive, credible, meaningful information that could create healthier deliberation?

I began looking at other similar suburban-microcosms like Madison – Cambridge, Mass., Chapel Hill, N.C., Ann Arbor, Mich., and Evanston, Ill. – all of which were close to major universities, suffered under noxious racial achievement disparities, and were committed to resolving them. And all of them were hyperliberal, even progressive, and yet still had difficulty navigating the tricky discourse around race. In all of them, I and my research team found intense, ongoing public dialogues about the gaps between White people and Black and Brown people, combined with frustration and confusion about why things have not improved much, a lot of defensiveness, and a keen desire to “do better.” In all of them, we found excellent, well-meaning journalists whose coverage of disparities consistently failed to meet the expectations and hopes of many in and those supporting marginalized communities. In all of them, we found community leaders, activists, and would-be politicians writing in blogs and Facebook, to bypass media in posts that often ignited healthy debate even as they also advanced political careers for those ensconced in the dominant White progressive hegemony, shifted power networks, and helped amplify conversations that had once been private. This book explores how we can improve public dialogues about race in liberal cities that should be better at such conversations.

On a deeper level, this book portrays a grand theoretical view of what’s happening with evolving media ecologies and the public information exchange at the local community level during the digital age. The conversation about how new technologies network our social, political, economic, and other lives is well underway. Despite the optimism that digital networks will diffuse power through entrenched structures, scholarly evidence has shown how online networks act as echo chambers for the powerful. In these spaces, offline inequalities not only persist but are exacerbated in digital spaces.Footnote 5 This book joins that dialogue and takes up where those studies leave us, grappling with how new social-media tools are reconstituting these networks and how power flows through these information-exchange structures. Using case studies from across the nation, my main goal is to examine whether journalists and other content producers can adapt reconstituted networks for new conversations, in keen consideration of the existing infrastructure governed as it is by dominant power constructs, embedded hegemony, and long-established institutions. To do this, I document the emerging media ecology for Madison, Wisc., and the roles taking shape within it. I will use field theory (from sociologist Pierre Bourdieu) to help me explain the power structures within that ecology via the overlapping fields of information-exchange (journalism, education). And I will use some light network analysis as a methodology to help me visualize the ecology.

In this work I reveal meaningful connections, identify key influencers, and uncover the ways in which the scaffolding of the information structure can be manipulated to incorporate marginalized voices. I argue that entrenched identity constructs in these liberal cities prevent the healthy heeding and other necessary components of trust building for true deliberation. Those seeking to promote an alternative message use social-media networks to bypass mainstream journalists in order to spread their messages, build trust, and gain social and political capital. But, they can be stymied by their own isolation in the network or come up against mainstream ideological forces. In these progressive or highly liberal places in particular, the political landscape served to hamper rather than ameliorate conditions for discussions. This is ironic, given that one of the stalwart tenets of a progressive ideology is a commitment to freedom of the press and to the free flow of ideas in civil society. Healthy community and vibrant democracy, progressives believe, depend upon open communication. Yet many White people who thought of themselves as social-justice advocates became defensive and hostile when forced to confront how White privilege had informed liberal policies, such as in the public schools, and led to exacerbated disparities. Though rich, deliberative conversations were happening on digital platforms in public spaces in most of these cities, many of them existed in isolated silos of talk away from the eyes and ears of major policymakers – and this effect is exacerbated in cities with decreasing media coverage. Essentially I am arguing that progressive ideologies become doxic (in field theory language) in the information-exchange fields. And those who practice progressivism in these places are governed so closely by this doxic mentality that they fail to see how exclusive the politics can be when exercised according to established norms of a place. That is, the thought leaders in these cities have accumulated so much political and civic capital through their networks that they can dictate what information circulates – and how it gets circulated. In the conclusion, however, rather than advocating for radical revolution, I consider how a careful recommitment to the ideal of progressivism with digital tools like social media and an understanding of networked, mediated ecologies can build the necessary social capital to shift these problematic dynamics.

Summer 2010: Kaleem Caire works with the Urban League of Greater Madison on a proposal for an all-boys charter school run by the Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) for high school. In August, The Capital Times newspaper writes an article about the plan.

Fall 2010: Caire hosts a large kickoff planning meeting for the school, asking for input from nearly three dozen community members on the details of the proposal. Several task forces are created to work on different aspects of the proposal.

December 2010: The MMSD Board of Education (BOE) hears the initial proposal. It would be all-boys, they would wear uniforms, classes would be all day and through the summer.

January 2011: The MMSD BOE asks follow-up questions of Caire on the proposal.

February 2011: Madison Prep gets sponsorship from two BOE members, including the Black president of the board at the time, James Howard, to move Madison Prep forward into a more detailed plan. Caire begins work on a federal planning grant application. During this same time period, protests erupt at the state Capitol as hundreds of thousands of people turn out to condemn Gov. Scott Walker’s assault on public unions, including school teachers. The Madison Teachers’ Union is dealt a devastating blow as Act 10 takes away its collective bargaining power.

March 2011: The MMSD BOE voted 6 to 1 to approve that $225,000 grant application. Caire puts together a team of leaders for the school, embarking on numerous meetings to persuade key influencers in the city of Madison Prep’s merits.

Summer 2011: Caire changes his proposal multiple times in response to critique from the Madison Teachers’ Union and BOE members. For example, the school went from being all-boys to co-ed, and he relents on demanding that all teachers be nonunion (holding strong on the mandate that the school’s counselors and social workers be of color).

September 2011: Caire wins the planning grant. He closes a meeting to discuss Madison’s achievement disparities to media and receives much pushback from local progressives and journalists.

December 19, 2011: The BOE hears public input for several hours before voting no to Madison Prep, 5 to 2. A follow-up motion to extend discussion of Madison Prep gets rejected as well. Caire vows to try to open it as a private school.

March 2012: Superintendent Dan Nerad announces he will step down and leave Madison.

April 2012: Arlene Silveira, who had opposed Madison Prep, wins reelection to the BOE, but Trek Bicycle Inc. executive Mary Burke (who was going to give Madison Prep $2.5 million to offset per-pupil expenditures and make the school more palatable to the BOE) won a seat. Two years later Burke ran against Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker for governor (and lost).

June: 2012: Nerad’s $12.4 million plan to address Madison’s achievement disparities gets chopped. The BOE passes a $4.4 million in initiatives (most of which merely enhanced those already in place).

January 2013: A primary race to replace BOE member Maya Cole becomes intense as a Latina, Ananda Mirilli, challenges two long-time White progressive activists in the city – Sarah Manski (whose husband was a leader in Progressive Dane) and TJ Mertz, a blogger and education history professor (also a member of Progressive Dane).

February 2013: Manski announces the day after she won the primary, with Mertz coming in second, that she was actually moving to California. People in the city cry foul with some hinting that the announcement was purposefully delayed until after the vote as an orchestrated move to keep a person of color who supported Madison Prep off the board.

March 31, 2013: The BOE election is held with Mertz uncontested on the ballot. Despite a write-in campaign for Mirilli, Mertz wins.

Spring 2013: BOE hires Jennifer Cheatham, a new superintendent who comes from Chicago with a major initiative to resolve K–12 racial gaps.

October 2013: The Wisconsin Council on Children and Families release the “Race to Equity: A Baseline Report on the State of Racial Disparities in Dane County” that shows Madison’s county to be among the worst in the nation on many metrics, including employment, education, and criminal justice.

December 2013: The Capital Times invites African American Rev. Alexander Gee to write a front-page column about his experiences as a Black man in Madison. This column is followed by another one by African American Michael Johnson. Also, a White BOE member who had voted against Madison Prep wrote a mea culpa, describing himself as “swimming in the water of White privilege.”

February 2014: The first meeting of what would become a movement called “Justified Anger” is held with eight hundred people coming together to talk about race in Madison. The next few years followed dozens of forums, training initiatives for White people in social justice, and other initiatives in the community. The Evjue Foundation, which owns half of The Capital Times, donates Justified Anger $20,000 in May 2014. The media organization joins with Wisconsin Public Radio to hold another forum on race in Madison, moderated by award-winning journalist Keith Woods from National Public Radio.

April 2014: The Capital Times announces a dedicated website called “Together Apart” to aggregate stories about race. It includes a history of African Americans in Madison.

September 2014: Superintendent Cheatham implements a new discipline policy in the schools, replacing a zero-tolerance program that disproportionately affected students of color.

March 2015: An 18-year-old biracial man named Tony Robinson who is unarmed is killed by a White Madison cop. Protests erupt.

June 2015: The Evjue Foundation awards another $150,000 to Justified Anger.

Summer 2015: The founders of Madison 365 begin fundraising for a news site about communities of color and issues of race. A Kickstarter campaign nets $10,000 and they go online in August 2015.

Here, it may be useful to unpack the term “progressive” politics as it is employed in this book. In Wisconsin, almost 20 percent of its residents identified as “progressive,” and it still had a small organization (called Progressive Dane) that ran campaigns. The label “progressive” emerged in all of my datasets in all the other cities as well. Conceptually, progressivism stems from the early-1900s Progressive Era of American politics. The excesses of capitalism, which emphasized individual economic success, were reined in by reforms that emphasized collective democratic governance and the revitalization of middle-class workers.Footnote 6 The foundation of this concept was that “Progressives were not revolutionists, it was also an attempt to work out a strategy for orderly social change.”Footnote 7 Progressivism focuses on “improving the lives of others” and presumes that “human beings were decent by nature, but that people’s and society’s problems lay in the structure of institutions.”Footnote 8 Social stratification and inequality were not predetermined by biology, history, or some other ontological category, but were historically contingent circumstances that could be remedied by the appropriate political reforms within the existing framework of socio-political action. In the midst of these political reforms, schooling practices took center stage as the site of social, political, and economic change. To many progressive educators, traditional educational models that presumed students to be passive recipients of information were wrongheaded approaches that didn’t prepare students for successfully navigating civic life.Footnote 9 What followed was a child-centered pedagogy that emphasized equipping children with the democratic tools to become active participants in the learning process and in their communities.Footnote 10

The problem with this model has been that these child-centered pedagogical practices were carried out in the midst of deep racial segregation. Leading progressive thinkers in education at the time made little to no mention of the Black experience in America and presumed that their color-blind approaches were sufficient.Footnote 11 This emphasis on shifting away from an individual student focus to a more communitarian educational paradigm meant that predominantly White communities would focus on predominantly White problems. The works of Black scholars like Carter Woodson and W. E. B. Du Bois made such failures more salient, emphasizing the unique social location of Black children in predominantly White spaces. In this progressive model of education, Black students were being “prepared to ‘begin the life of a White man’,” yet were “completely unprepared to face the harsh realities of a segregated labor market and a society saturated with prejudice and discrimination. Black students who wanted to pursue journalism, for instance, were trained how to edit a paper like The New York Times, ‘which would scarcely hire a Negro as a janitor’.”Footnote 12 Furthermore, the colorblind approach of progressivism preaches tolerance, but largely eschews proactive forms of racial reconciliation in the development of educational policies, as scholars have seen in Houston,Footnote 13 Raleigh-Durham,Footnote 14 and New Orleans.Footnote 15 These dynamics become all too clear in the story of Caire and Madison Prep, as well as the other racially segregated, liberal hubs examined in this book. For those who practice this kind of politics, this exercise transcends votes and signs, and achieves paradigm status, a way of life, and an identity; in field theory terms, we would call this governing belief system a kind of “doxa,”Footnote 16 which I will define more comprehensively shortly. And for those who wish to challenge the status quo in these places, the question becomes what is the best way to counter all of this and strive for change? Leverage networks and various kinds of capital to work within the progressive doxa or call for a revolution? All of this is important to think about as we move through the cases and the public’s discussion of K–12 achievement disparities.

As a progressive liberal myself, I believe in funding our public schools, paying teachers more, increasing government safety nets such as welfare programs, social security, and other programs, and reforming institutions to making them more democratic with more engaged citizens. I’ve long considered myself “racially aware” and knew enough to know we were not in the “postracial” America so many championed after President Obama’s election in 2008. However, as a White person who grew up in a tiny, seacoast town in a northeastern state with very few people of color, I had had little experience talking about race until college, and I interacted with very few people whose skin looked different than mine. Until I embarked on this book, my White privilege occupied all of me with nary an awareness of its presence. This venture parallels my own racial journey, as I moved beyond the recognition of my White privilege and sank into what my racial stake means for my research. Peppered with personal memoir, the book at hand relates my uncomfortable experiences during interviews as reflective of the paths these progressive cities will have to take to better facilitate community conversations about race. From the first awkward conversations where I was called out for failing to build trust with the parents whom I wanted to participate in my focus groups, to the final interviews when my connection with informants merely highlighted how long my own journey will be, a strong reflexivity informs this work. I contended with my stubborn conceptions regarding proper engagement in an interview, for example, and the dominating role of researchers in focus groups. Even as I interviewed Caire and others about the charter school, I also felt conflicted about the idea of such a venture and was sympathetic (but not convinced) to the arguments in opposition. I struggled, in other words, with the very power dynamics and identity confliction I uncover and interrogate in these communities.

Next I am going to explain the concept of media ecology, as I am using it, and talk about how I found the framework important in the documentation of how social media was changing the manner in which information flowed. Media ecology privileges different media and their production actors as well as helps to isolate information flows – making it very useful to snapshot how digital technologies might be creating new roles and transforming mediated relationships. However, media ecologists do not seem to be in the forefront of power dynamics that dictate how and why those mediated relationships play out in the ways that they do. For this, I turned to another conceptual framework – Pierre Bourdieu’s field theory – which helps explain the particular structuring of these ecologies in these mid-sized, progressive communities. I explain the field contribution to this book after the next section on ecology.

Emergent Media Ecologies and the Networked Fields Within Them

A Media Ecology

In early 2010, Kaleem Caire was still in Washington D.C. working on President Barack Obama’s Race to the Top school reform initiative. But he and his wife Lisa Peyton Caire were contemplating a move back to the Midwest with their kids. Caire had grown up on Madison’s south side and graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2000. It was home and family beckoned. At the time, I was looking around for a new project and after spending a lot of time studying how newsrooms worked and citizens acted given digital technologies, I was keen to understand the more macro structures at work in those organizational and individual productions. I formed a research team and we started taking an accounting of all the media players in our community of Madison, Wisc., to see how it was being reconstituted by digital platforms in information exchange. I wanted to somehow show its media ecology – which I define as the constellation of news organizations, blogs, social media, and other mediated content platforms that connect us in local community. It quickly became clear that we had to focus our efforts around a particular topical area such as politics or education because so many niche-oriented websites and blogs, hashtags, and Facebook group pages had emerged. Choosing education as our niche, we finished this in early 2011 – just as protests broke out at the Capital because of Gov. Scott Walker’s assault on teacher and other public unions. By that time Caire had come back, become head of the Urban League, and introduced his proposal for the Madison Prep charter school. Though I had never researched race specifically, I knew racial achievement disparities in the K–12 schools would help us narrow in on an ecology and also reveal important moments of power differentials between those ideologically dominant and more marginalized groups of citizens. Plus the timing of K–12 racial disparities were right because Caire was just proposing Madison Prep. So my team recorded all the mainstream publications online and offline as well as the blogs, hashtags, public Facebook Group pages, and websites that produced anything at all on racial disparities, especially Madison Prep. And before we knew it, we had documented a media ecology. But what did that mean exactly?

The ecological argument builds on a biological metaphor (in terms of structure, evolution, and systems), and over nearly a century in sociology it has been applied to everything from urban settings to professions. For groundbreaking theorists such as Odum,Footnote 17 the metaphor forces an examination of the whole, especially at a time when academics were studying the phenomena piecemeal. At first, medium theorists Marshall McLuhan (of “medium is the message” fame) and, later, Neil Postman, postulated about the “study of media as environments.”Footnote 18 Postman first formallyFootnote 19 adapted the metaphor to communication systems in thinking about how language, imagery, and other material ways of relating to each other constituted its own media ecology. In this school of thought about media ecology, the theoretical focus centered on the technologies of communication – in other words, the technical constructs of information.

But I am also interested in how sociologists co-opted the metaphor to understand how people and media were interconnected, using each other to create and recreate systems and structures in ecology-like ways. James Carey emphasized the ecological linking of citizens to each other as well as to an imagined national (and, ultimately, international) community through media.Footnote 20 As in biological ecologies, new communication technologies evolved the media ecology to be more fragmented as groups became more connected to their competitors, Carey wrote: “For example, each ethnic group had to define itself which meant each had to know, understand, compete, name, and struggle against other ethnic groups inhabiting contested physical and symbolic space.”Footnote 21 In Media Ecologies, Fuller argued that media comprise the environment, but they do not make up a static scaffolding. I am using the two approaches together: not only does the interplay between media continually reshape the ecological environment (a PostmanFootnote 22 postulation) but also the interactions between media and humans have the potential to express power relationships, create patterns of inequities, and subvert.Footnote 23

For my purposes in trying to capture Madison’s media ecology, I had to remember that all ecologies, therefore, are fluid and continually in flux – growing, pulsing, contracting in places, birthing new appendages, etc. Ecologies in general, though, are more concerned with a collective “species” (such as journalists but also all the other content producers working in relationships with the information flowing) than with individuals such as a single reporter. Media ecologists examine actors in relation to one another, as well as their role in the collective. Media ecology is about one’s movement in a space as part of a complex system that entails networks of networks, linked within an amorphous system without discrete borders.Footnote 24 As open systems that depend on outside environments, ecologies evolve constantly and the actors within work together in synergetic ways but also in constant competition for resources. So looking at the information ecology we had laid out for Madison, Wisc., around education issues at a certain point in time during 2011–2012 I could see groupings of mainstream journalists, progressive bloggers, and education and other activists as regular Facebook posters. I could see from our documentation how new individual actors such as Caire, newly arrived from D.C., and others were creating new kinds of actor groups and changing the very nature of the ecology and how information was flowing through it. Even emails, memos, and other private correspondence that prior to social platforms never would have been widely distributed were now becoming of some consequence for the ecology.

But as I watched the story of Caire and Madison Prep unfold, I became intrigued at the other things that were happening. Veiled (and not-so-veiled) racism tainted, obscured, and dominated the flows of information and mediated bits of content. Internal fighting and past personal conflicts also seemed to influence postings, even news accounts. An individual’s digital savvy propelled his or her commentary to prominence in the community dialogue. But even someone who seemed to be well positioned in the ecology in terms of relationships and resources didn’t act or achieve in ways that we might expect, given that positionality. Why? The particular problem of the media ecology we had documented – that of K–12 racial achievement disparities – and my desire to also investigate these power relationships at work meant I needed a similarly robust theoretical framework to explain what was happening within the ecology. While media ecology provides a powerful metaphor for capturing information flows, it has somewhat less to say about the power dynamics that shape those flows. I landed on the conceptualization of journalism as a “field” – that is, a system made up of actors that is networked according to power relationships and social positions.

How Fields Structure Ecology

When Caire began the public discussion in Madison about the charter school for Black boys, he entered a media ecology with nesting information-exchange fields that included not only journalism but also content-producing influencers in the school system and in education in general. Two century-old media organizations, an alternative weekly, television networks, radio talk shows, ethnic news organizations, and a dozen or so blogs characterized journalism in this city. The field of education included the school-district administration and board of education, filled with progressives who were prolific as bloggers and Facebook commenters as well as adept at working large networks that encompassed social, professional, and civic spheres in the town. Spread across both of these interlocking fields were progressive politicians intent on keeping the status quo intact and activists aiming to dismantle it. Together they made up a large, complex information-exchange field that operated according to certain rules and helped maintain the status quo within a macro media ecology.

But let’s step back a minute and just wrap our heads around the idea of fields within a media ecology. Stemming originally from the physical sciences, the sociological approach to field theory arose as a way to observe and analyze how political institutions work, control their environments, effect change, deal with interlopers, and evolve in society on a large scale.Footnote 25 Although several core threads of field theory exist, this book is most concerned with the work of French sociologist and philosopher Pierre Bourdieu, who thought of the field as comprising relational actors with strategic goals competing for dominance within a hierarchal structure.Footnote 26 Using Bourdieu as one main source, Neil Fligstein and Doug McAdam defined “strategic action fields” as “mesolevel social orders as the basic structural building block of modern political/organizational life in the economy, civil society, and the state.”Footnote 27 In other words, action fields comprise the media ecology.

Fligstein and McAdam advanced Bourdieu’s work into a more comprehensive offering that incorporated how actors’ individual conceptualization of identity and construction of meaning direct their actions with a field. This idea of identity construction within a complex system of power relationships, organizational/institutional realities, and networks of producers and audiences fit with what I wanted to capture. In a significant application of field theory to immigration coverage in American and French news, Rodney Benson heralded the theory as a framework for understanding power relations in journalism.Footnote 28 He wrote that field theory

is crucially concerned with how media often serve to reinforce dominant systems of power. Yet compared to hegemony, the field framework offers the advantage of paying closer attention to distinctions in forms of power, how these may vary both within a society and cross-nationally, and how they might be mobilized for democratic purposes.Footnote 29

Key concepts of field theory – the ones I will be most engaging with in this book – are doxa, habitus, path dependency, and capital. As I mentioned above, I think of doxa as one’s paradigm from which one operates through life as a set of beliefs and “determines the stability of the objective social structures.”Footnote 30 Habitus enacts doxa; that is, that which exercises one’s way of seeing the world and enacts the relationships one has with it.Footnote 31 If doxa are the rules of the game, habitus is the practice.Footnote 32 Path dependency is essentially how what actions that were taken previously will help determine the direction of any new path. The successful utilization of these – doxa, habitus, and path dependency – can yield capital for an actor in the field. Capital can be social, political, economic, and also informational, which Bourdieu might consider “cultural” or “symbolic.” And sometimes it can be all of these things at once. It is in essence a kind of currency used in a system of exchanges between parties. Furthermore, those in positions of power tend to wield forms of capital more and better than those who are not.Footnote 33 I am looking at only the public information-exchange world here, thinking about how one can gain or lose the ability to influence people through what they say in the media, post in a blog, or write in a Facebook status update. In this book, progressive ideology structured people’s actions as actors – both those dominant and established as well as those challenging the status quo – spent and attained capital through their content production in public spaces.

For the purposes of this book, my overarching media ecology is determined by the overlapping information-exchange fields of journalism and education:

Journalism:

Bourdieu defined the field as being made up of reporters, officials, and activists (and other sources) and audience members, who act and react constantly as agents within an industry constrained by a series of organizational, institutional, political, social, and other forces. A combination of political, economic, cultural, and symbolic capital ensures a journalistic agent of its position in the field, which shifts constantly on the whims of everything from power plays to audience tastes to rising platforms to economic realities.Footnote 34 “Journalists are caught up in structural processes which exert constraints on them such that their choices are totally pre-constrained.”Footnote 35 Their actions in the field tend to be “path dependent,” which is the idea that previous actions will shape any new path. Once these paths are established, it is difficult to diverge from them, at least according to the neo-institutionalists.Footnote 36 Many press scholars have investigated the forces at work in the institution that shape reporters’ habitus. For example, we know that in power indexing of sourcing, journalists are trained to reach out to experts and officials for stories. They fail to be inclusive.Footnote 37 Journalists as agents tend to define the parameters of any social problem via the “right” sources.Footnote 38 One could conceptualize this as a path-dependent phenomenon of habitus: that is, reporters have a hard time choosing different sources because of the practices established previously, the expectations that have developed in the newsroom, and the information capital that had been gained in the past by such behavior. The more built legitimacy, authority, and social capital a source, reporter, or news organization has accumulated according to the “rules” of the field, the more influential in terms of being quoted, getting something published, and receiving attention in the overall media ecology.

Education:

Scholars have applied Bourdieu’s conceptualizations such as habitus and social capital to school systems.Footnote 39 This field includes school officials and administrators, youth-oriented nonprofits, academic education experts, teachers, students, and parents, among others. Actors within the education field use information exchange to vie for position in the field and influence education policy.Footnote 40 Performance improvement can be achieved by tapping into relationships that generate rich social capital and offer access to the resources necessary to achieve success.Footnote 41 But field position can also be a major reason for academic disparities, according to some research. For example, Bourdieu and Passeron argued that students bring disparate levels of cultural capital to school from their home, where different economic and cultural conditions prepare kids unevenly for their position in the field.

Bourdieusian fields are hierarchal at their core, meaning the actors within them occupy certain positions according to their class, race, professional title, social networks, etc., and these fields in my progressive cities reflected these traits. In my case studies, some people wielded much more influence – such as being cited by others in public content – than others in terms of the public information available about the gap, whereas others worked more behind the scenes but their names rarely appeared in print. Still others used digital technologies to connect with niche publics, not caring whether their words echoed beyond that community, while several prominent bloggers in different cities each parlayed their writings into political candidacies that ultimately won them election to the school board or city council. Each individual occupied positions in the field according to his or her social, professional, and civic networks as well as how much decision-making power he or she held in the system. And most importantly for this book, journalists performed their jobs according to long-established field norms and routines that perpetuated the White-dominated, progressive-directed status quo.

This discussion evokes the dominant themes that run throughout this book. In order to appreciate how these fields work within a media ecology in a digital age, I will examine how authority, privilege, power, and trust are being exercised and used to promote and share information. Additionally, I analyze the way these forces work to persuade, influence, and inform various acting citizens in the public. In this book, I track these specific dimensions of the field, thinking about them as conceptual agents whose presence (and absence) manipulate the information flow within the overarching ecology. While field theory doesn’t have much to say about “technologies” or information platforms per se, media ecology does. And while media ecology allows a broader capturing of who and what are determining information flows, field theory can help understand the why and how around the central power questions we have. Close scrutiny of the dynamics that shape how people communicate about issues of race in public, mediated spaces highlight how old roles of production such as journalists are adapting and how new roles such as bloggers and social-media posters are making an impact. More importantly, an understanding of these processes within these two nested frameworks can help us to overcome obstacles and employ strategies toward improving dialogue in the future.

Authority, Privilege, Power, and Trust in Local Media Ecology

Years after the Madison Prep vote, Kaleem Caire was invited to talk about leadership at a Madison downtown event sponsored by the local progressive news organization, The Capital Times. In his remarks at the public library during a chilly November night in 2016, he touched on authority, privilege, power, and trust as he reminisced about the community dialogue around the charter school. He told the story of another local community leader, a White man named Steve Goldberg (executive director of CUNA Mutual Foundation and a well-known activist in the city) who addressed the large crowd at the December 19, 2011 hearing when the school board voted on the charter school. Caire said:

I’ll never forget it. He was very brief. He told the Board of Education, he said, “you know, you guys, sometimes to gain power and to gain respect, you have to be willing to give up power and give respect.” And so I say to people who are asking how do we get more leaders of color into positions of power: “Even I. Even I have got to be willing to give up my authority so that someone else’s authority can emerge. I’ve got to be willing to give respect to other leaders so that I can also gain respect but so that that respect that that other person can share with the rest of the world can show too.”

For Caire, it is only when privilege, authority, and power are wielded in consideration of what the entire community needs that community trust can develop and thrive. Yet, authority, privilege, power, and trust manifest via doxa, social capital, and habitus; they are how an actor such as a journalist retains status in a field, moves position, and influences other actors. I could write four books each on authority, privilege, power, and trust, but that’s not my aim. Instead, I wanted to think about them in play together within the grand case study of Madison, Wisc., and a series of micro case studies in other cities – Ann Arbor, Mich., Cambridge, Mass., Chapel Hill, N.C., and Evanston, Ill. By observing the interactions of authority, privilege, power, and trust, we can begin to understand how important their presence (and absence) are for public talk as well as to highlight how digital technological agents might help diffuse power structures in this information-exchange world.

BourdieuFootnote 42 equated “authority” to symbolic capital because its possession depended on the social recognition that comes with political, economic, and other kinds of power. In press scholarship, authority is defined as “the power possessed by journalists and journalistic organizations that allow them to present their interpretations of reality as accurate, truthful, and of political importance.”Footnote 43 Like Furedi, Foucault, and others, Matthew Carlson argues authority must be thought of as a relational concept such that it must be granted and accepted. In addition, he notes that authority depends upon its exclusion of others’ articulations of knowledge.Footnote 44 He draws on Bourdieu’s understanding of fields as existing in conjunction – embedded and overlapping, but also in competition and in synergy – with other fields, and suggests authority plays a central part in how actors in those fields relate to one another. Journalistic authority, writes Carlson, is something constantly negotiated with every new project, every new interaction between media organization and sources or audiences – especially as interactivity restructures the traditional hierarchy of influence among all the players of information flow.Footnote 45

In education, authority discussions tend to revolve around the moral authority of a teacher or the authority a parent might have over her kids’ schooling.Footnote 46 But I am interested in how might education researchers conceptualize authority as it relates to the schools’ relationship with the community, particularly as it manifests in public spaces. Education has its own institutional dynamics and hierarchies that affect what gets said in the public sphere. Like journalism, education is facing its own authoritative challenges – and has since the time of philosopher and education theorist John Dewey, who wrote in 1936:

We need an authority that, unlike the older forms in which it operated, is capable of directing and utilizing change and we need a kind of individual freedom unlike that which the unrestrained economic liberty of individual has produced and justified; we need, that is, a kind of individual freedom that is general and shared and that has the backing and guidance of socially organized intelligent control.Footnote 47

This is such an appropriate statement for this work at hand, isn’t it? But the question remains: how is this “individual freedom” playing out in a local community, especially in terms of authority? This will be a major engagement throughout this work.

For Black people, authority is not as benevolent a topic as it might be for White journalists or educators, especially if we are talking about the authority that exists in institutions (like the schools and the press) that have historically marginalized them. Institutional racism abounds in both the schools and the press, which has been well documented. How would people of color, then, appreciate such authority? Many, many scholars have looked at the differences with which middle-class White people can approach an authoritative institution like the schools compared to someone whose skin is somewhat darker or whose economic class is somewhat lesser. One reason for the achievement gap might be the way in which families of different classes feel comfortable engaging with authorities. And communities of color have long been suspicious of mainstream information outlets where they rarely find positive representations of themselves. They themselves do not feel authoritative in these spaces, with these actors. Merely suggesting that people of color become active, show up in mainstream public spaces, and let their voice be heard does not account for the power dynamics at work that have created generations of intense distrust. This is in part because if authority is indeed a form of symbolic capital that derives from political or other kinds of capital, then people who do not have a ton of money, power, or influence historically in the progressive networks that govern information-exchange fields might find it elusive.

I want to spend some time talking about the role of trust in authority, privilege, and power. A complex concept, trust “is a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another.”Footnote 48 For my purposes, trust represents an essential element for the positionality of professional journalists in any local community information flow as well as an instrumental technique to attaining authority. Trust must be attained, like capital, and is something that can be gained and lost fluidly. Örnebring theorized the profession of reportage is authoritative because of its “trustworthiness,” which is in turn a result of its autonomy and independence from faction.Footnote 49 Journalists answer a higher call than an individual operating as a single actor and take part in a collective movement regarding community information, reporters from around the world told Örnebring. It is this sense of societal duty that engenders a kind of trust: “The straw-man citizen journalist is outside this collective, outside the system of shared knowledge and controls.”Footnote 50 But this is basically a kind of institutional trust.

In public forums, trust takes on an additional role, a more social role.Footnote 51 Robert Asen examined school boards in Wisconsin to understand the components of healthy deliberation as it yields good decisions in public. His major point is that trust is essential to deliberation but must be done as part of a relationship and as a form of engagement between individuals. Without interaction between two actors, trust will not emerge. He writes:

When interlocutors craft a trusting relationship, they may address district issues efficaciously in making decisions about policy that may not thrill all stakeholders but nevertheless constitute reasonable decisions that holdouts can understand. When interlocutors do not enact trusting relationships, their deliberations break down, divisions harden, and recriminations abound. In especially troubling cases, the failure to build trusting relationships threatens the very possibility of deliberation itself.Footnote 52

Asen holds a similar idea of trust as Carlson does of authority: Trust is a relational construct – something enacted through practice by individuals, something that can ebb and flow with new actors, new procedures, new relationship dynamics and over time (and I would add, dependent upon place or platform as well). Asen and other scholars have noted the following qualities as necessary in building trust for good dialogue: From Asen, flexibility, forthrightness, engagement, and heedfulness; from Byrk and Schneider, respect, competence, personal regard for others, and integrity;Footnote 53 and from Mayor, Davis and Schoorman, ability, benevolence, and integrity as well.Footnote 54 As with authority, others must perceive an individual as being trustworthy. And it develops and exists over time, offering not only a template from past interactions but also the opportunity for future relationship work. Hauser and Benoit-Barne write that trust is “a process that relies on the familiar in order to anticipate the unfamiliar.”Footnote 55 This can be problematic if the past relationship eschewed trust or operated according to a paradigm of distrust, as we will see in my cases.

It is at this point we see how trust as a relational practice is inevitably caught up in issues of power and privilege. When two people come together to discuss publicly a racially charged issue such as an achievement gap, differing positions of vulnerability can inhibit a smooth exchange of information. I saw this over and over in the examples given from our participants for this book. We would have a working Black parent articulate a personal experience, afraid to be too specific lest her complaint become public and the school retaliate against her school-aged son. She didn’t trust that the officials would allow her to be forthright without repercussions. She told of experiences in the schools or with the press where promises were made and broken. She spoke of distrust specifically and refused to speak to reporters or to attend hearings. This parent existed in the same space as one of our elected school board members with a popular blog, friends in high positions, and kids who did fine in the system – in other words, lots of political, civic, social, and symbolic capital. The school board member trusted the institution because the system had proven beneficial for him and his family. These different positions contain different levels of intimidation and risk for the actors. As Asen articulated, “explicit and implicit discursive norms may place uneven burdens on participants to justify their positions.” Patti Lenard notes that “extending trust expresses a willingness to put oneself in a position of vulnerability” but “when one comes to feel vulnerable more globally, extending trust (and thereby exacerbating one’s vulnerable condition) becomes more difficult and less likely.”Footnote 56 This vulnerability stymies reciprocity in the trusting relationship. It also forestalls the willingness of someone in a risky position (or even a perceived risky position) to participate – especially in the public realm. Asen optimistically suggested that practicing the dimensions of trust he laid out – flexibility in a stance, forthrightness in dialogue, engagement with individuals and a heeding of ideology – in context and in conjunction would surely bolster overall trust and foster good deliberation. But my data suggest that even if an individual practices these qualities of trust, if the partners at the hearing or in the commenting sections hold a perception of their own vulnerability, no engagement will happen at all. This advances Asen’s notion that trust is as much about the interaction as it is about any individual actions or perceptions.

Thus, we might hypothesize that even those marginalized must not only acknowledge their lack of trust and their feelings of vulnerability, but also attempt to overcome these feelings. Engage despite feeling vulnerable. Participate even in consideration of past injustice from the same parties. Is this a reasonable statement and expectation? In theory, perhaps, but in practice we are faced with an intractable problem – at least on the face of it. I suggest that making this statement results in what Nancy Fraser would call “status bracketing,” which means moving forward with deliberation as if all the players were of the same social class, gender, race, distinction, etc.Footnote 57 Asen, Fraser, and Young all place the burden on those in positions of power to facilitate an open space for discussion.Footnote 58 Indeed, it is one of my contentions in this book that journalists in particular are in a unique position to develop neutral places for this kind of engagement to happen. News spaces online are a place to start the trust-building process. Yet, first the immense distrust that reigns between journalists and their communities must be overcome. And this can only be done through individuals – like superintendents or reporters – and not in the name of the institution or organization they represent, necessarily. In the stories we were told for this book, individuals were trustworthy; institutions were almost always not.

During my data collection, I witnessed journalists engaged in this “status bracketing” too (that is, assuming all of their sources operate under the same mantle of communication or information privilege), which brings me to my point and a major purpose of this book: how can journalistic spaces be used to build (and restore) trusting relationships? The story of one reporter’s sourcing decisions exemplifies the problems that status bracketing can create in coverage of education issues. The news organization wrote a piece about the zero-tolerance policy of the school system for kids who make mistakes such as bringing alcohol onto school property. The reporter profiled a White middle-class honors student rather than a student of color to highlight how unreasonable the district’s discipline policy was. Many in the Madison community believed this coverage spurred action on the part of the school board to revise the discipline policy for the district. The uneven school discipline implementation had existed for some time among Black students, and many in town described the reporter’s choice of a White student to tell the story as somewhat racist: why not have done the piece using a Black student and highlighting the persistent disparities and systemic racism at work in the district’s policies?Footnote 59 The reporter wrote in a special column how she couldn’t get any students of color to go on the record but that the White student and her family offered both to be named and welcomed the coverage:

I would have happily written about either – and I’m pretty sure most reporters who know a good story would have also jumped at the chance. But you can’t write an in-depth human-interest piece on the effect of school policy on minors without the buy-in of a minor and her family. … There are lots of important stories that unfortunately get away because they need to be told from the inside out.Footnote 60

Here, framing her decision in the color-blind cloak of institutional journalistic values (such as needing named sources), the reporter absolves herself of any responsibility to create a safer space for a family that would have had much more to lose in speaking up than the family that offered to speak. Furthermore, she discounts how much easier it is for a middle-class White family accustomed to advocating for themselves to advance their cause within a system run by people who look and operate like them. Even in childhood, White, middle-class people are encouraged to speak out, and know that the public sphere belongs to them.Footnote 61 Compare this to a family who has reason to distrust an innately biased system, one that offers their son a 50-percent chance of graduating on time, one that has long discounted and disadvantaged their children. Many people – particularly those of lower economic status – feel little empowerment to question authoritative institutions like the schools or the press. Should the reporter here have dealt with these authority, privilege, power, and trust realities in some way? Offering anonymity perhaps or creating a different kind of forum for that side of the story to come out? Of course!, you might argue. The issue, however, is complicated: this is a traditional reporter who abides strictly by norms that had been set in the field long before she took up pen and paper. She is merely reinforcing her position in the field and doing what any other reporter would have done. As someone who herself spent more than a decade in newsrooms as a traditional print reporter, I can tell you how entrenched reportorial protocols are, how conceptualizations of what constitutes credibility and truth are innate to the very identity of journalists, and how one’s job security depended upon the reporter’s exercising these essentially codified routines toward building authority. To break from the institution and act as an individual would counter her instincts for job security. My goal is to document the process of local-community information exchange in the digital age. That includes detailing the ways in which power structures shape that exchange, how field challenges are poking the establishment seeking change, and the constant field-domain boundary struggles over local-community knowledge.

Documenting Fields within Ecologies

Documenting fields within a media ecology is tricky. Typical techniques by themselves would not begin to reach the three levels of analyses (micro-meso-macro) that I would need. I detail everything I did for this project in the appendix, but the gist involves a fairly new method called network ethnography, which combines quantitative network mapping with qualitative community ethnography, rich textual analysis, and in-depth interviews. “Network ethnography” is used as a way to observe a community in action by thinking about that community as a network and combining some light network analysis with qualitative techniques such as in-depth interviewing and textual analysis. Coined by Philip Howard in 2002, network ethnography offers a way to study a community that is also steeped in what Howard called “hypermedia organization” online, a way to consider in context not only what one is observing in the physical world but also what occurs virtually.Footnote 62 The method served as an effective analytic device for C. W. Anderson’s diagramming of the Philadelphia media world.Footnote 63 He employed some brief network analysis to determine who and what to study in the overarching ecology of his site – with great success. Similarly, in Madison, I was able to conduct some limited network analysis to demonstrate how the information-exchange relationships were becoming networked in the public realm. I used this information, which visually showed me the information flow (and which I will demonstrate in Chapters 2 and 3) and its major influencers, to direct me in the next phase of the study – in-depth interviews, community observation of hearings and meetings, and both content and textual analyses. In five case studies, I and various research teams conducted more than 120 interviews of major information players – journalists, bloggers, activists, and commenters – in addition to analyzing more than four thousand news articles, blog posts, Facebook updates, and their comments. I supplemented this data with three focus groups totaling 15 citizens from both Black and Brown communities to provide a unique perspective on those voices not in this public content stream as well as ten interviews with international leaders in communication about race.Footnote 64 All of the network maps depict Madison; the four other cities of Chapel Hill, Evanston, Ann Arbor, and Cambridge represent micro-case studies meant to corroborate and substantiate the Madison themes. In sum, I used network ethnography as a methodological technique to document an emergent media ecology and its information flow as well as how that ecology was structured hierarchically with action fields in a deep dive that is rarely performed in media studies.Footnote 65

This method allowed me to tell the full story of one progressive city in the Midwest struggling with talking and writing about racial disparities in public mediated spaces. I tracked how its communicative ecology evolved over a period of 4–5 years by analyzing the fields within it. It is a story of distress, no doubt, as we learn of the seemingly inevitable obstacles that line the path toward improved racial justice dialogue and note how people’s information-exchange strategies reflect domineering habits of ideology and history that make up the place’s doxa. But it is also a narrative meant to inspire as we witness the communicative changes in this city from the beginning anecdotes in 2011 to the 2015 disruptions that came with the brand new, provocative Madison365 website, significant new money from traditional institutions for a social movement, proactive hires of journalists of color, the thriving Black Lives Matter work, and other actions that in aggregate offer a much different environment for public talk and networked voices than had existed just a few years prior.

Outcomes and Opportunities Within a Media Ecology

At its core, this book is concerned with how the journalistic field and its boundaries of performance can change at a meso level by looking at micro actions on the part of individual actors in relation to internal structural developments. By 2016, the information-exchange field in Madison, Wisc., looked very different from the one Caire entered in 2011, as a result of the communicative efforts of Caire and others around this issue. The interactive capabilities of the Internet – that is, the abilities of nonprofessional journalists, activists, citizen bloggers, and others to produce content and relay evidence alongside reporters – are innately changing the dynamics of our fields. Bourdieu argued that when a new actor performs in new ways within a field (i.e., assumes a new position), the entire field shifts to accommodate the new activity. Those previously dominant may become “outmoded.”Footnote 66 He wrote: “As Einsteinian physics tells us, the more energy a body has, the more it distorts the space around it, and a very powerful agent within a field can distort the whole space, cause the whole space to be organized in relation to itself.”Footnote 67

New public spaces enabled by technologies within the overall media ecology abound – commenting spaces, forums, Facebook posts, blogs, Twitter, and other social-media platforms – and these spaces for information flow also represent opportunities for movement within these fields. Many scholars have expounded on how social-media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook are creating a networked culture in which informational authority is waning and new patterns of knowledge flow are emerging.Footnote 68 Shirky argued the “new ease of assembly” of information has meant a new “ability to share, to cooperate with one another, and to take collective action, all outside the framework of traditional institutions and organisations.”Footnote 69 This empowerment, posited Tapscott and Williams,Footnote 70 results in a more horizontal power distribution of information and could mean a mass collaboration of information production and exchange that leads to a more fruitful, efficient, and knowledgeable democratic society. People of color in particular have taken to digital outlets for expression, dialogue, the creation of counterpublics, and other connections, networking, and sharing. In her book characterizing the relationship between Black people and the media, Squires wrote:

The research and observations collected here suggest that people of African descent have launched internet initiatives in great numbers, and, perhaps, may be on the verge of having more control as individuals and as groups over this medium than any other since the use of paper and ink dominated mass public communications.Footnote 71

Ideally, social-media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter could be used to change the power dynamics in any field, particularly for the field positions of marginalized groups. As Heinrich stated: “This is a sphere where hierarchies – at least in theory – do not exist.”Footnote 72 It’s not a giant leap to consider the minorities’ growing use of social-media platforms might offer an opportunity for change. I am arguing that these new places of public commentary alongside journalism – sometimes disguised as journalism – offer opportunities for bridging communities, social action, and field change.

Of course, there are several problems with this assumption, not least of which is the digital divide that continues to plague cities such as those in our sample. Only half the Black and Brown parents in the Madison Metropolitan School District in my Wisconsin case study give the school an email that they check regularly. Some research has suggested subordinated cultures give up (or adapt) and rebuild their own field on the edges, away from the mainstream.Footnote 73 Another reality is the ways in which these communities’ relate to technologies according to their position in their field, level of social and cultural capital, and “habitus.” These factors limit the benefits of technology. For example, one study reinforced Bourdieu’s contention that one’s poor economic circumstances, inability to increase social and cultural capitals, and demoralizing habitus stymie a person’s movement within the field.Footnote 74 Furthermore, these fields – journalism and education – operate according to a White majority paradigm whose systemic policies and insular professional and social networks tend to benefit majorities and reinforce marginalization.Footnote 75 In general, some scholars have offered a cautionary note to all the idealized rhetoric about the utopian world digital technologies may bring. For example, Beckett and Mansell point out that even with new spaces of flows engendering the possibility for egalitarian deliberation, the opportunities for rife misunderstanding also exist. “The new forms of journalism that are emerging today will not achieve their potential for enhancing a public service environment if the new opportunities are treated simply as a way to securing ‘free’ content to compensate for cutbacks.” They recommend scholars critically approach research questions and sites of inquiry like the one I have here in Madison and to be particularly concerned with “power, its redistribution, and its consequences for those engaged in the production and consumption of news.”Footnote 76

In examining the effectiveness of communicative patterns in discussions about the achievement gap, this book offers insight into the mechanics of public information exchange at the community level in the digital age. It looks at the quality of the discourse and the barriers to good public talk, but also questions how the promises of digital communication are challenged when contentious issues arise. This book is divided into two parts. Part I provides the theoretical framework for the data in the aim of advancing the scholarly conversation around media ecology, field theory, and journalism. In the first chapter, I lay out how I want to document an emergent media ecology, explaining its structure using field theory, and delving deep into the major themes of information authority, privilege, trust, and power in mediated racial discourse within progressive places. I explain why marginalized voices have difficulty being heard and how those facilitating public discourse on race issues reify existing exclusive structures. In the end, who succeeds in getting their voice heard and their content seen depends upon how much symbolic information capital they have attained, their position in the field, and their choice of a posting platform. Often, the more visible their writing, the more influence they have. But this effect is mitigated by the actor’s position in the field as well, and his or her practice of the progressive doxa in these case-study cities. Chapter 2 describes the emerging communicative ecology in Madison, Wisc. specifically. It explains how social media is reconstituting the ecology, who remains marginalized, and how communities and media are networked. It provides network maps of who is producing content in which channels. I argue that new roles are emerging in the reconstituted media ecology, and that each of these roles occupies networked positions of potential power in the fields that make up that ecology. This typology represents the early work we did on documenting the ecology. Also in Chapter 2 I frame out the notion of boundary work, and demonstrate how it throws up obstacles to successful public talk in journalism and other journalistic spaces. Boundary work offers a way to talk about how our community actors are working the public information-exchange field to be heard – or why they may try to become visible but have no luck. Chapter 3 shows how these roles play out in the information flow of Madison during my study period given social media and other kinds of digital production. I found, for example, how prolific blogging and posting for some in these cities built sufficient symbolic capital to lead to election to public office – political power. This chapter argues that how one can achieve information authority expands within these emergent ecologies. These three chapters demonstrate the process of local–community information exchange in the digital age, the ways in which power structures shape that exchange, how field challengers are poking the establishment seeking change, and the constant field-domain boundary struggles over local–community knowledge within a macro-mediated ecology.

For those readers less interested in the esoteric academic speak of ecologies and fields, skip ahead to Part II. These chapters apply my typology to these locales and shows how information moves within and between the journalism and education fields to constitute an overall media ecology. Chapter 4 reveals the boundary struggles of this landscape, both in the public content and in the interviews with the most prolific content-producing actors, including journalists, bloggers, and activists. I look at what inhibited good public discussion in Madison and in the four other liberal cities, specifically the role of White reporters and their institutional practices. For example, objectivity and other boundary struggles are both perceived and explicit obstacles inhibiting not only information exchange itself, but also the influence any information might have. Chapter 5 analyzes the strategies being employed to overcome these hindrances of information exchange and offers insight into what strategies appear to be successful and what makes others fail. I consider how people attempt to build information capital in this conversation. Those challenging dominant discourses call on alternative legitimation techniques such as experiential storytelling but lack the networks for effective amplification. I find three techniques of strategy prevail: repetition across and within platforms, the making of dynamic dialogues, and the taking advantage of the fluidity of public and private networks, particularly in the sense of border crossing. Finally, Chapter 6 explores the ways in which evolving networks of information exchange can substantially alter the way a field is working, and thus reconstitute the umbrella media ecology. It characterizes successful discourse and explores whether social media can alleviate problematic exchange. How might digital technologies be employed in the building of symbolic capital for individuals? While Chapter 6 is the most optimistic in the book, I also confront the themes of information authority, privilege, power, and trust as they change with new and old agents acting with digital technologies. I argue for a recommitment to progressive ideals as well as foundational tenets of journalism and suggest that reporters, bloggers, activists, and others who want to improve community dialogues tap into digital networks by way of offline connections to create the trusting, heeding kind of spaces necessary for deliberative exchange. This concluding chapter includes a series of recommendations for how those interested in producing content for public information exchange in such cities might approach that dialogue.

Conclusion

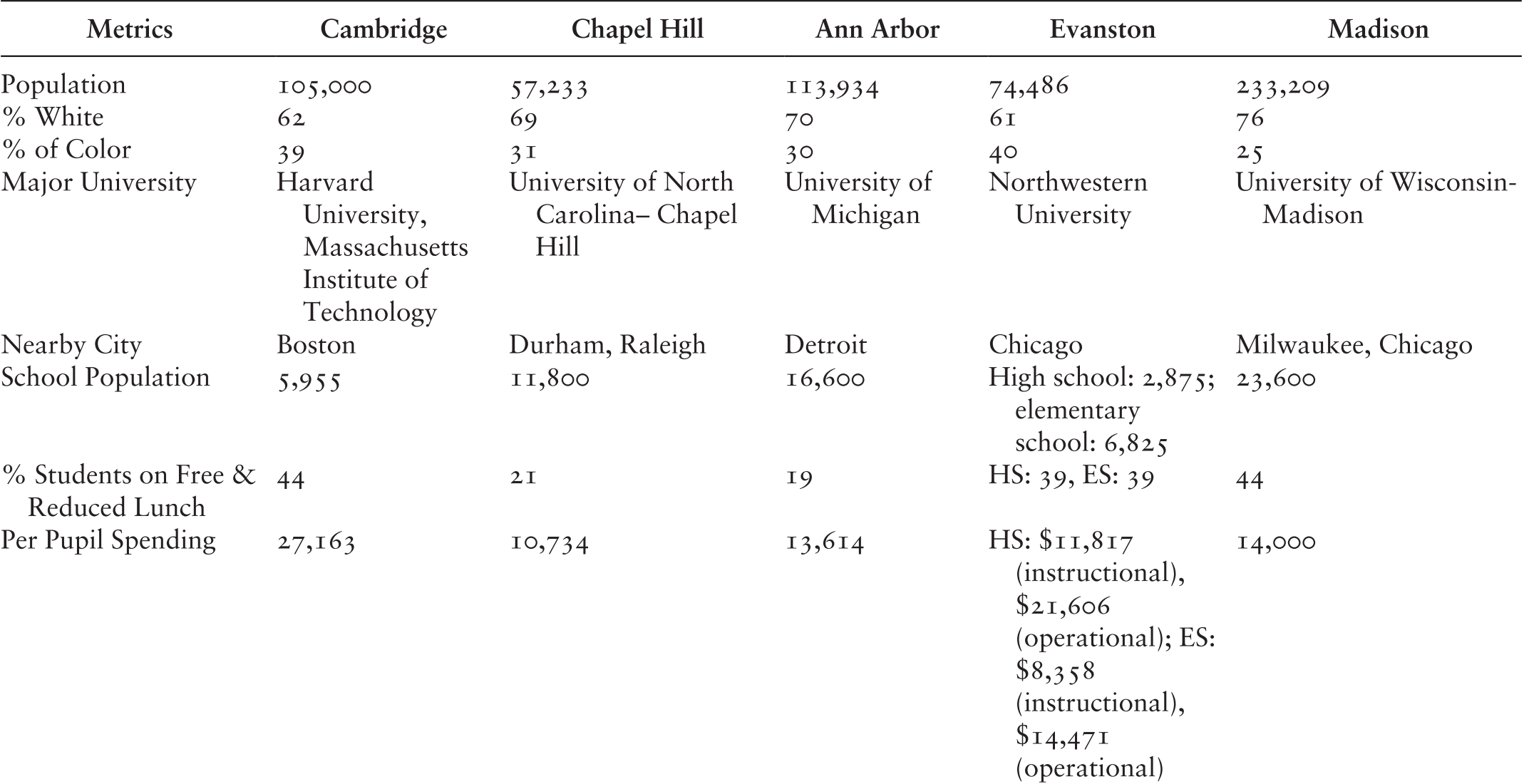

This book aims to tell a story of one community as it grapples with a constantly changing media environment, constrained by legacy organizations and their active boundary work, and reflective of the uncertain world of social media and blogs pushing new (and also redundant) interactive content. Four other cities serve to corroborate the themes the macro case study revealed: all of the cities are highly educated but with a growing population of children in poverty, all have a majority White population but have schools made up of increasing diversity, and all have a keen commitment to progressive values such as good public schools. See Table 1.1 for a breakdown of these communities’ demographics.

Table 1.1 Case study demographics (2010–2013)

| Metrics | Cambridge | Chapel Hill | Ann Arbor | Evanston | Madison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 105,000 | 57,233 | 113,934 | 74,486 | 233,209 |

| % White | 62 | 69 | 70 | 61 | 76 |

| % of Color | 39 | 31 | 30 | 40 | 25 |

| Major University | Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology | University of North Carolina– Chapel Hill | University of Michigan | Northwestern University | University of Wisconsin-Madison |

| Nearby City | Boston | Durham, Raleigh | Detroit | Chicago | Milwaukee, Chicago |

| School Population | 5,955 | 11,800 | 16,600 | High school: 2,875; elementary school: 6,825 | 23,600 |

| % Students on Free & Reduced Lunch | 44 | 21 | 19 | HS: 39, ES: 39 | 44 |

| Per Pupil Spending | 27,163 | 10,734 | 13,614 | HS: $11,817 (instructional), $21,606 (operational); ES: $8,358 (instructional), $14,471 (operational) | 14,000 |

| % White Students | 36 | 58 | 57 | HS: 48, ES: 44 | 51 |

| % Students of Color | 59 | 42 | 34 | HS: 52, ES: 56 | 49 |

| Metrics | Cambridge | Chapel Hill | Ann Arbor | Evanston | Madison |

| Population | 105,000 | 65,700 | 117,770 | 75,658 | 243,000 |

| % White | 66 | 73 | 73 | 66 | 80 |

| % of Color | 34 | 27 | 27 | 34 | 20 |

| University | Harvard, MIT | University of Chapel Hill | University of Michigan | Northwestern | University of Wisconsin-Madison |

| Nearby City | Boston | Durham | Detroit | Chicago | Milwaukee, Chicago |

| School Population | 6,019 | 12107 | 17,104 | 3500 (high school), 5975 | 27,000 |

| % Students on Free & Reduced Lunch | 44 | 27 | 22 | 28 | 48 |

| Per Pupil Spending | 27,163 | 10,872 | 11,645 | 22,100 | 14,000 |

| % White Students | 39 | 52 | 55 | 44 | 44 |

| % Students of Color | 61 | 48 | 45 | 56 | 56 |

And yet all also report deep rifts around the issue of race, using words like “distrust” and “blind spots” and “defensiveness” to describe the communal racial climate. In Chapel Hill, one White politician in town said: