Classical normative theories of deliberative democracy assume that citizens have an undifferentiated capacity for public deliberation and treat it as a taken-for-granted capability. In academic analyses that have followed, the concept of deliberation has been largely used as a heuristic standard for characterizing the quality of discussion and decision-making among citizens on issues of public relevance and community life. This is based on the original understanding of the public sphere as an inclusive discursive sphere where citizens participate as equals with similar fluency and flare in public discussions. But, it is now recognized that the idea of the public sphere was founded on privileged participation by select groups of people and favored rational argumentation as a discursive style (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1980, Reference Mansbridge and Macedo1999; Fraser Reference Fraser1990; Benhabib Reference Benhabib1994; Elster Reference Elster1996; Mouffe Reference Mouffe1999; Young Reference Young and Benhabib (ed.)1996, Reference Young2000; Sanders Reference Sanders1997; Polletta and Lee Reference Polletta and Lee2006; He and Warren Reference He and Warren2011; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge, Heller and Rao2015). Many social groups were marginalized and many narrative forms were excluded.

Fraser, for example, has written about the historical construction of the “public sphere” in Europe and the United States as a masculinist site and has characterized the conception of deliberative democracy as bourgeois masculinist (1990, 62). Her work draws on the revisionist historiography of Landes (Reference Landes1988), Eley (Reference Eley and Calhoun1992), and Ryan (Reference Ryan1990) to highlight the irony that a discourse of publicity celebrating accessibility, rationality, and equality was used with the strategic aim of constructing class and gender distinctions in the public sphere. Mansbridge has also contributed to the feminist critique of deliberation by arguing that

a history of relative silence makes women political actors more likely to understand that when deliberation turns into theatre, it leaves out many who are not, by nature or training, actors. When deliberation turns into a demonstration of logic, it leaves out many who cannot work their emotionally felt needs into a neat equation … Many shy men are quiet, but the equivalent percentage of shy women is increased by learning silence as appropriate to their gender. (1998:152)

Taken together, these critiques acknowledge that the capacity to engage in deliberation differs among individuals and social groups. They also suggest that inequalities arising from social stratification along class, caste, and gender divides influence women’s and men’s ability to participate in deliberations of a public and political nature.

In India, gram sabhas were mandated and created with the inclusive egalitarian intention of promoting participation of all voting citizens in village development and governance. Indeed, as we have seen, in some states citizens were repeatedly exhorted to participate in larger numbers in democratic deliberation. But, at the same time, India is a country marked by extreme inequalities among social groups. A core dimension of inequality in India is literacy defined by the Indian census as the ability to read and write with understanding in any language. Literacy captures both social and economic disadvantages. The illiterate people in a village are also likely to be the poorest and to belong to socially subordinated castes and tribal groups. As a corollary, low-literacy villages are likely to have a greater percentage of socially and economically disadvantaged people. In this chapter we explore how citizens’ capabilities to engage in gram sabha deliberations may be affected by inequalities in literacy. Fortunately, our data allow us to explore in a preliminary way how gram sabha deliberations vary between villages at varying literacy levels.

Scholars of Indian politics, even those studying panchayat level politics and performance, have not given due analytical importance to how literacy matters for political participation and deliberation. An exception is Akhil Gupta (Reference Gupta2012), who in his work on bureaucracy, structural violence, and poverty in India, engages in a discussion on the role of literacy – specifically, the ability to write – for the functioning of democracy in India. He focuses on the critical role of writing in a bureaucratic system that requires written communication between the government and rural citizens and the associated bureaucratic demand on villagers to submit complaints and petitions about public services and subsidies in writing. He argues that in a society where literacy is highly stratified and highly correlated with class and gender, this requirement leads to bureaucratic domination. But the view that illiteracy leads to “bureaucratic domination” through the administration’s demand for written communication “overestimates the importance of writing and underestimates the political capacities of the poor” (p. 192). Poor citizens in Indian democracy have alternative avenues of political action.

One such alternative political avenue that does not require written communication is participating in gram sabhas. There illiterate citizens can verbally communicate with agents of the state and register complaints and petitions vocally. Gupta’s argument seems to suggest that literacy might not play a critical role in participation in governance through public deliberation. Further, Gupta draws a distinction between two types of literacy, formal and political literacy:

The Indian experience demonstrates that the procedures of democracy do not require literacy and that a vigorous democracy can flourish in the absence of formal literacy. What is far more essential is political literacy, and … political literacy does not depend on formal literacy as a precondition. (p. 220)

Bhatia (Reference Bhatia2013) has made a similar point, critiquing the biases in theories of deliberative democracy by drawing on non-Western experiences of the public sphere and political communication, and showing that literacy is not a necessity for deliberative democracy to function in semiliterate societies.

We treat these arguments as an invitation to examine empirically the role of literacy in the gram sabha. We explore whether literacy makes a difference in how rural citizens deliberate – the capacity to articulately frame demands, voice complaints and concerns, question authority figures, and hold panchayat members and public officials accountable. Through our qualitative explorations of hundreds of recordings of gram sabha meetings we hope to offer our observations on the connection between formal literacy and political literacy of the kind relevant for participating effectively in the gram sabha.

Methodology

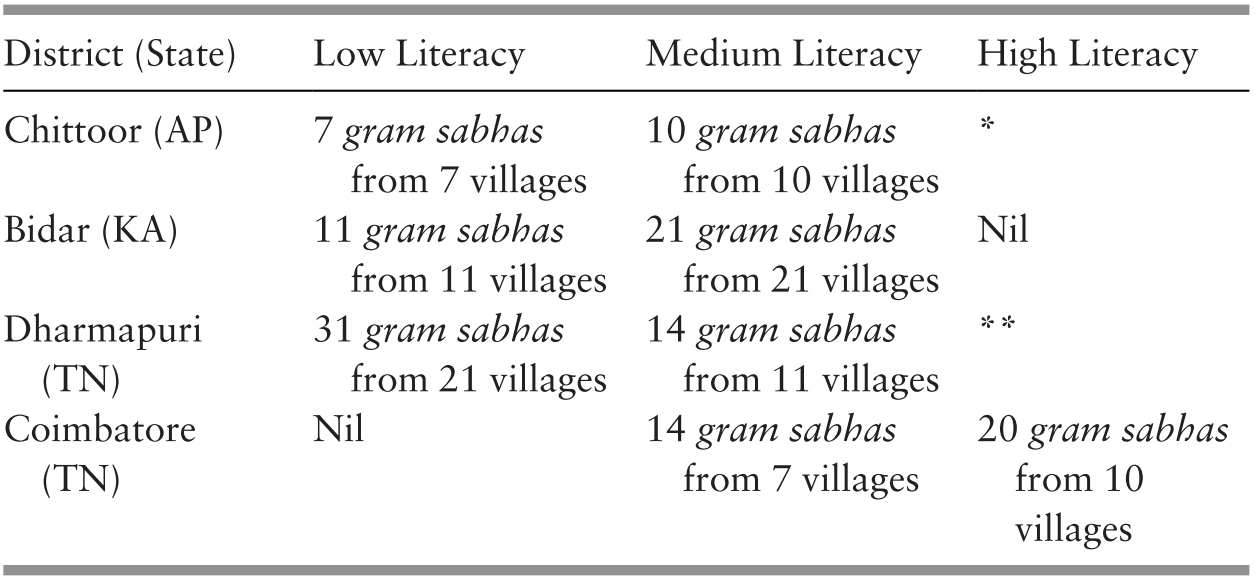

We follow the Indian census to define literacy as the ability to read and write in any language. The cutoffs we use in our study are based on the literacy data from the 2001 census. The latest 2011 census data are also included to show the magnitude of subsequent changes.

Since it is impossible to accurately know the literacy status of individual speakers at the gram sabha, our methodological strategy has been to rely on the village literacy level. This is a practical compromise that allows us to examine whether literacy affects the collective capacity for civic deliberation and if it makes a difference with regard to the nature and quality of gram sabha deliberations. We have used village-level literacy data from the 2001 national census to distinguish between low-literacy villages (less than 33 percent of the population literate), medium-literacy villages (more than 34 percent and less than 65 percent of the population literate), and high-literacy villages (at least 66 percent of the population literate). This categorization has enabled us to identify the different literacy contexts within which the sampled gram sabha deliberations occurred.

| Census 2001 | Census 2011 | |

|---|---|---|

| Rural Literacy Rate | Rural Literacy Rate | |

| Kerala | 90 | 93 |

| Tamil Nadu | 66 | 74 |

| Karnataka | 59 | 69 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 55 | 60 |

| All India | 59 | 69 |

We have restricted our analysis to within-district comparisons, comparing gram sabhas in villages in the same district but with differing literacy levels. This is intended to prevent variations between districts in other factors from influencing our identification of possible differences stemming from literacy alone. For example, by comparing gram sabhas in low-literacy villages with those in medium-literacy villages in Bidar, Karnataka, we can isolate differences in the capacity for and quality of deliberation. And by eliminating the possibility of other structural differences in gram sabhas at the district and state level, we can attribute any variations in the capacity for deliberation and its quality to differences in village-level literacy with a higher degree of certainty.

The samples from Dakshin Kanada (KA) and Kasaragod (KL) had only high-literacy villages; therefore, there is no within-district comparison for these.

| District (State) | Low Literacy | Medium Literacy | High Literacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chittoor (AP) | 7 gram sabhas from 7 villages | 10 gram sabhas from 10 villages | * |

| Bidar (KA) | 11 gram sabhas from 11 villages | 21 gram sabhas from 21 villages | Nil |

| Dharmapuri (TN) | 31 gram sabhas from 21 villages | 14 gram sabhas from 11 villages | ** |

| Coimbatore (TN) | Nil | 14 gram sabhas from 7 villages | 20 gram sabhas from 10 villages |

Notes on data excluded from the literacy-based comparisons:

* The sample had only one high-literacy village from which only one gram sabha had been sampled. This has been left out of the comparison.

** The sample had only 3 high-literacy villages from which 4 gram sabhas had been sampled. These have been left out of the comparison.

The sample from Pallakad (KL) had 18 high-literacy villages from which 30 gram sabhas had been sampled and only 2 medium-literacy villages (3 gram sabhas sampled) and 1 low-literacy village (2 gram sabhas sampled). Because the sample was overwhelmingly high literacy, it has been left out of the comparison.

Our method of comparison limited our sample to three states and only to those districts within which there was significant literacy variation. One unavoidable limitation of our data, as stated previously, is that we do not know the literacy level of the individual speakers. Another limitation is that villagers who attended but did not speak up (who were very likely to be illiterate) were not observable in the data because they were silent. Silence in deliberative forums as large as gram sabhas is hard to study, and we are limited to analyzing people’s utterances. This problem is intensified in low-literacy contexts where illiterate villagers may be silent and literate villagers may dominate the discursive space. We are restricted in our analysis therefore to understanding how the village literacy context (not individual literacy) shapes the manner and content of what people say at the gram sabha and the ways in which villagers collectively communicate with elected leaders and state officials.

Summary of Findings

Through inductive analysis of the transcripts we identified core elements of political literacy that enabled villagers to be effective participants in the gram sabha. The level of political literacy on display at gram sabhas varied by the village literacy level in the anticipated direction, with gram sabha deliberations in medium- and high-literacy villages showcasing participants’ greater political literacy than those in low-literacy villages. Political literacy with respect to the gram sabha centered on villagers’ knowledge and understanding of four key spheres of government activity pertaining to rural development and governance: public finances; public infrastructure and facilities; publicly funded household and individual benefits; and the functioning of public offices and officials.

Having command over each of these spheres required specific abilities. Having a grasp over public finances required being able to understand panchayat budgets, including the conditions and constraints on using panchayat funds and government allocations, understanding financial disbursements made to contractors for undertaking public works projects, and being able to question discrepancies. With regard to public works, villagers needed to be able to suggest and justify resource and infrastructure projects for village development and provide specifications for the suggested works (such as location and some technical details) to the extent their experience allowed. They needed to be able to hold the panchayat accountable for the proper execution and quality of public works and to understand government specified public contribution rules for certain public works projects. Regarding government subsidies and benefits, villagers needed to provide informed participation in the beneficiary selection process for BPL (below poverty line) targeted schemes, question misallocations and nepotistic practices, and ensure that benefits were given to the most deserving villagers. Finally, villagers needed to know how to bring pressure on elected leaders and bureaucratically appointed public officials and how to hold them accountable for their performance by challenging absences and corrupt practices.

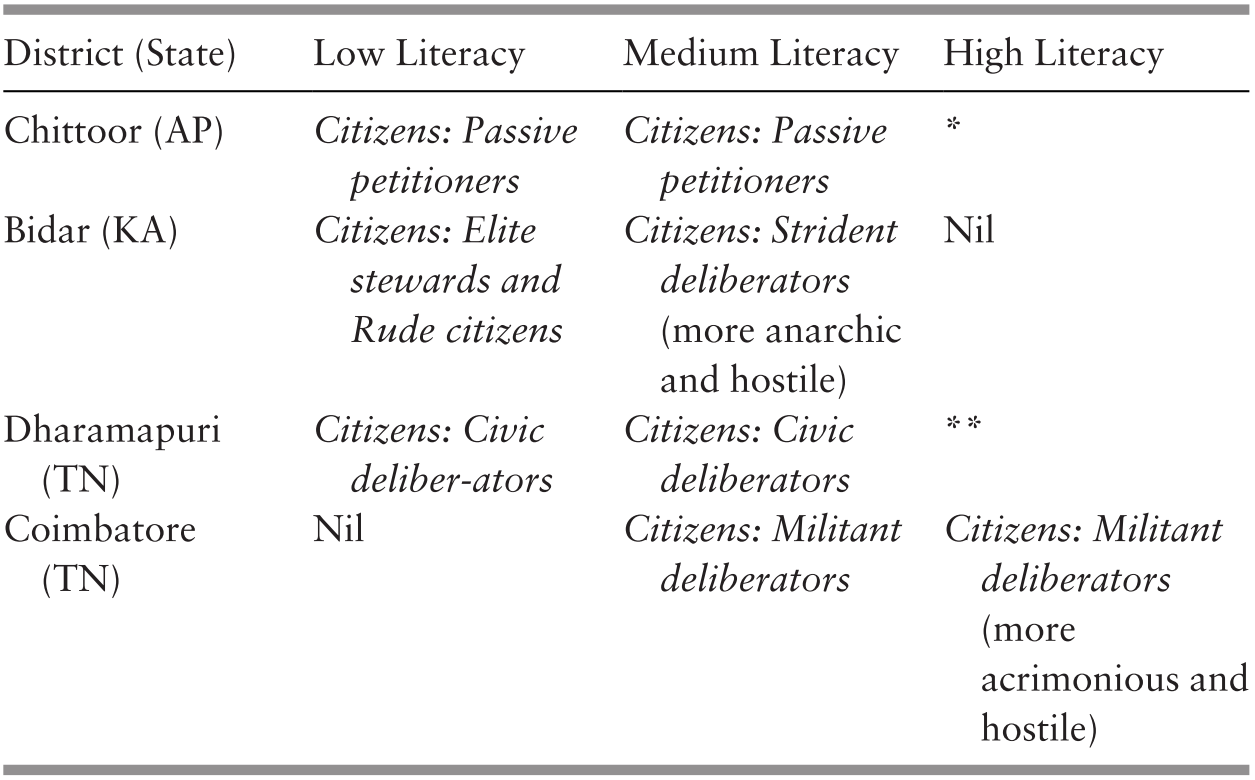

As anticipated, in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, states that had been supportive of the panchayat system since its inception, the level of political literacy on display in the gram sabha was positively associated with village literacy level. High-literacy contexts revealed greater political literacy than medium-literacy contexts, which in turn displayed greater political literacy than low-literacy contexts. However, an important caveat is that the magnitude of difference in political literacy between similarly differing literacy contexts across states could vary a great deal. In Karnataka, the gap in villagers’ political literacy and the nature of deliberation between villages differing in literacy was wider, whereas in Tamil Nadu, the gap was much narrower. This pattern is very likely tied to the state-level influence discussed in the previous chapter and possibly other intersecting influences that vary by state (such as women’s membership in self-help groups).

Gram sabhas in Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh, were an exception to this pattern. Here the village literacy level did not make any difference to the political literacy on display in the discussions or to villagers’ capacity for deliberation. Gram sabhas in both low- and medium-literacy villages were similarly lacking in deliberation, and the difference in village literacy level did not get reflected in any substantive difference in quality. This, too, was likely because of state-level factors since, in Andhra Pradesh, the panchayat system had been historically subverted in favor of alternative governance structures.

We conclude that formal literacy (determined from census data on village literacy levels) makes a positive difference by enhancing villagers’ political literacy and capacity for engaging the state through deliberation. But we also note that the extent of the difference is influenced by how the state modifies the structure and functioning of the gram sabha system. Although formal literacy does make a positive difference to gram sabha deliberations, state-level influence on the political construction of the gram sabha can override the effect of formal literacy on political literacy and the capacity to deliberate. Positive state influence can make up for the deficiency in literacy, as in the case of gram sabhas in low-literacy villages in Dharmapuri, Tamil Nadu. Contrastingly, negative state influence can suppress whatever advantages higher formal literacy might have in terms of political literacy and the capacity for deliberation, as in the case of Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh.

Our analysis yielded other interesting patterns. In gram sabhas in low-literacy villages in Bidar, Karnataka, there appeared to be a consistent recurring pattern of villagers with higher political literacy, who were also likely educated, helping other villagers to engage with the state. This pattern of discursive intervention by those having greater political literacy to facilitate villagers’ participation in deliberations was not present in gram sabhas in medium-literacy villages in Bidar. Instead, in the medium-literacy villages, it seemed that a more diverse group of villagers spoke up in the gram sabha. They were often strident when talking to panchayat and public officials. As a result, the deliberative atmosphere in gram sabhas in medium-literacy villages in Bidar was sometimes chaotic and cacophonous. In addition, in Bidar, Karnataka, and Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, gram sabha deliberations in higher-literacy villages were marked by more acrimony and hostility than those in villages with comparatively lower literacy levels. From this particular pattern we speculate that literacy may have the effect of broadening the base of vocal participants who are articulate, and this can sometimes have an unexpected effect. Rather than always making discussions more orderly, having a larger proportion of villagers who can give voice to their frustrations with perceived government negligence and inadequacies can make gram sabhas more anarchic.

The influence of village literacy on gram sabha deliberations is complex and defies easy simplification. While some of the effects are in the anticipated direction, others we found surprising and counterintuitive. We provide evidence of our findings by sharing extended excerpts from the gram sabha meetings along with our commentary.

PAIR 1. CHITTOOR, Andhra Pradesh: 7 Low-Literacy Versus 10 Medium-Literacy Gram Sabhas

We have argued that, in Chittoor, villagers had very little knowledge about the goings on of the state because there was no information dissemination on public income and expenditures or reporting on the progress of village public works and ongoing government schemes. Villagers were therefore forced into the role of passive petitioners who could only submissively complain, petition, and supplicate. Careful comparison between gram sabhas in low- versus medium-literacy villages within Chittoor revealed virtually no difference in the issues people brought up or the mode of their articulation. The bulk of the verbal interjections made by villagers were brief statements of problems and equally terse demands for responsive action by officials. The expected differences in the quality of deliberation due to low versus medium village literacy seemed to be obstructed by a state that had, for political reasons at the time, undermined the federally mandated panchayat system in favor of its own parallel governance systems.

| District (State) | Low Literacy | Medium Literacy | High Literacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chittoor (AP) | Citizens: Passive petitioners | Citizens: Passive petitioners | * |

| Bidar (KA) | Citizens: Elite stewards and Rude citizens | Citizens: Strident deliberators(more anarchic and hostile) | Nil |

| Dharamapuri (TN) | Citizens: Civic deliber-ators | Citizens: Civic deliberators | ** |

| Coimbatore (TN) | Nil | Citizens: Militant deliberators | Citizens: Militant deliberators(more acrimonious and hostile) |

Low-Literacy Gram Sabhas

Articulating Demands

The following excerpt records typical articulations of problems from gram sabhas in low-literacy villages. Villagers name problems and demand relief briefly and without describing or contextualizing their concerns and claims in any detail. The statements are devoid of financial and technical queries and considerations. No sustained discussions result from their interventions:

Villager [male, SC]: My name is Muniraju. In this village sewerage facility is absent. Drains should be repaired.

Villager [male, SC]: Village roads are in a bad condition and it will be better if cc [cement/concrete] roads are laid.

Villager [male, SC]: We can tell our problems here. We want a path to Kanikapuram village as the current path goes through the forest and it is not safe.

Villager [male, SC]: Roads are not in good condition. We need a road from Bheemunicheruvu to Kanikapuram

Villager [male, SC]: Should develop drainage lines.

Villager [male, SC]: Cement roads are absent in the village. They have to be laid.

Villagers’ minimally stated petitions and supplications here reflect the lack of the knowledge and experience necessary to frame demands and complaints effectively. They fail to demand accountability from panchayat members and public officials for the execution of public works, or properly scrutinize budgets and beneficiary selection.

Medium-Literacy Gram Sabhas

Articulating Demands

Gram sabha deliberations in medium-literacy villages were very similar to those in low literacy villages. Villagers stated their problems without outlining the context or specifying the details or tying their presentation of situations to a clear demand for redress:

Villager [male, SC]: Water pipes are damaged in Jangamali Kandrika.

Villager [male, SC]: We have no cement roads; when it rains it is problematic for us.

Villager [male, SC]: In Ramapuram our houses are in the low-lying areas and water is coming into the houses.

Villager [female, BC]: We have no drainage facility. Drain water is stagnating at different places.

Villager [male, SC]: We have no cement roads, water tank, and burial ground.

Requests and demands are articulated in nonassertive ways, as if they were merely tentative suggestions being offered to panchayat officials:

Villager [male]: Streetlights are getting burnt regularly. Water is leaking from the pipeline and this should be repaired.

Villager [male]: For the cost of laying cc roads the government is giving 70% grants, so if panchayat people give 30% it would be good.

Villager [male]: We should have metaled roads.

President: We will lay tar roads.

Villager [male]: Tar roads are to be laid.

President: I have enquired about it. Soon we are going to lay roads. We have talked about roads with some people and in the rest of the village bores were installed by us.

Villager [male, OBC]: Water bore is to be installed in our area. There is one bore nearer to ‘Tellagunta’ from which water is not flowing properly. Please check that one.

Villager [male]: There are no electricity poles in our area and at least three more poles are to be provided.

Questions from villagers on budgetary details, financial outlays, and technical aspects of project implementation were conspicuously absent during these discussions. It appears that villagers did not know how to press for information regarding budgets and implementation or how to demand accountability. From this we conclude that formal literacy is not enough to ensure robust deliberation or improved village governance. The state can stifle the role formal literacy is expected to play in improving villagers’ political literacy and enhancing their capacity to deliberate. And this may suppress the potential for participatory democracy represented by the gram sabha.

PAIR 2. BIDAR, Karnataka: 11 Low-Literacy Versus 21 Medium-Literacy Gram Sabhas

In Bidar, in low-literacy villages we found polarized participation between rude citizens and elite stewards. Rude citizens showed their inability to properly articulate demands and complaints and spoke with state agents in a discourteous manner. Elite stewards, a smaller group, made frequent instructional interventions in the public discourse, trying to coach the former group in the proper framing of demands for public resource and infrastructure. The substantive proceedings reflected the large gulf in political literacy, arguably reflective of the divide in formal literacy among the participants. In medium-literacy villages in Bidar, gram sabha deliberations were strikingly different. Villagers across varying levels of political literacy all spoke freely, often in a raucous manner. This resulted often in verbal fights and created an atmosphere that, at times, bordered on the anarchic and contentious. Villagers in these meetings acted as strident citizens who boisterously made demands, sought information, and held authorities accountable.

Low-Literacy Gram Sabhas

Articulating Demands

Gram sabha meetings in low-literacy villages in Bidar displayed a clear divide between villagers with and without political literacy who possessed widely differing capacities for deliberation. Basic understanding of the public’s critical role in deciding common infrastructure and resource demands was lacking among a section of participants. The following excerpt records a villager who thinks that a committee should decide their development needs and another villager, an elite steward, who intervenes to correct his misunderstanding. Even after repeated requests to voice their demands, villagers keep returning to the issue of turn taking among caste groups rather than specifying the public resources they need:

Nodal officer: You need to finalize which half-done pending works are to be completed and what new public works are to be taken up. You should tell us.

Villager [male]: You may have a committee for that. You can decide what are the works to be done for which areas. We are not necessary for that.

Villager [male]: Villagers need to decide in the gram sabha.

Joint engineer: We will tell what is there from our end. In this action plan, we can execute roads that are half-done.

Nodal officer: You decide and tell us your ideas.

Joint engineer: After road, if we have money left, we will do whatever you say.

Villager [male]: No, now you [villagers] tell us what you want, they (officials) will look at those things later.

Secretary: 50% general and 50% to SC-ST.

Villager [male]: How much?

Secretary: 50% to general, 50% to SC-ST.

President: We need to divide general into three and SC-ST into three.

Villager [male]: Ok. Divide like that and do one work in one place.

President: Which works are to be completed?

Villager: [male]: One time you take up a work at our end, next time you take up a work at their end.

Villager [male]: Take up one work for general [castes] and take up one work for SCs.

It was common for villagers to raise multiple demands simultaneously and fail to mention specific details, such as start and end points of the roads requested. Villagers also failed to understand the public contribution requirement for some government projects, like road construction. On the whole, villagers are able to voice needs but fall short of tailoring their participation to fit the parameters of government programs. In some meetings they also fail to agree on the resources most in need.

Villager [male]: We need to have three stages [raised platform for hosting ceremonies and events].

…

Villager [male]: We want cc road.

Secretary: We need to pay 10% from the panchayath [for financing road construction].

Joint engineer: You need to pay 5%.

Secretary: We need to collect taxes and pay for that. But in our panchayath we cannot collect any taxes.

Villager [male]: Sir, there is a budget for stage, no?

Joint engineer: That will come under Jala Nigama. Now you tell about roads and drainage.

Villager [male]: What cc road we have, it should not be through any member. We want it directly from the government.

…

Secretary: If we fulfill the amount of public contribution [for road construction], it can be done.

Villager [male]: That is why we are telling. Let them [government] do the work and let all the [panchayat] members put in the required money.

Villager [male]: We want cc road.

Secretary: Tell us from where to where. We need to put in money to cover 10% of the cost.

…

Villager [male]: Let us take up the road first.

Secretary: Tell from where to where

Villager [male]: Road and drainage.

…

Villager [male]: No work is done in our place. We want to have a stage.

…

Villager [male]: We want roads and latrine in our village.

Villager [male]: Yes, the latrine funds got diverted.

Villager [male]: We don’t want latrine.

By contrast, the following excerpt records a sophisticated framing of demands, with villagers specifying the start and end points of roads they want to be built. The framing reflects a good grasp of the kind of deliberation that is effective in obtaining government projects.

Villager [male]: What are all the things you have noted for ward 4?

Secretary: Laying of cc road from the well.

Villager [male]: Which well?

Secretary: Open well.

Villager [male]: Madharagalli, you write it. It is an open well. Vishwanata’s house, Madharagalli.

Secretary: Toilets near Kolachamma mandir. CC road between Cheare Shankar’s house up to Ramanna’s house. CC road between Naggeri’s house up to main road.

Villager [female]: Not there. Ramanna Gante’s house to Ambedkar Bhavan

Secretary: Is it cc road?

Villager [female]: CC road to be laid from Venkappa Pandaragere’s house to Sirivantha Kumbar’s house.

Nodal Officer: Is there any water problem? You are telling only about cc roads!

Villager [female]: We have bore for water, so no problem. But major problem is that of road. The water flows onto the roads and it gets filthy; we can’t even walk on it. So we have written both.

A bifurcation in villagers’ ability to grasp what is required of them in deliberative exercises and their ability to articulate their demands is prominent in the low-literacy gram sabhas in Bidar.

Seeking Accountability

Even in low-literacy settings, villagers put pressure on panchayat officials and seek accountability from them. The divide in discursive styles caused by differences in political literacy was prominent in such exchanges as well. The following excerpt records poor Lingayat villagers bringing charges of corruption against officials for their allocation of government land for building houses. Interestingly, a villager comments on participants’ discursive style, stating how becoming angry led them to fight in the gram sabha. This was a participant’s attempt to explain the frequently observed discourteous behavior of himself and others, which he claimed gave them a bad reputation:

Villager [male]: All SC people have houses in their ward. But people from our Lingayat community don’t have houses.

Villager [male]: At least will you allot sites [for building houses] here? We don’t even have sites.

Villager [male]: We have two to three children in each house. Panchayath people will give sites to [SC families with] two to three children. They will not come and see. They will take money and give it to them. They will allot side by side and eat up the money.

Joint engineer: Tell me, after my arrival to whom have we allotted sites? We have given to none.

Villager [male]: I am warning you, don’t conclude this gram sabha!

President: I am not doing so.

Villager [male]: A site [notice] got hung in Narayanappa Gundappa’s land.

Secretary: Who, I don’t know! Chairman did it, go and ask him.

Villager [male]: Why will we ask him! He personally came and measured it. You go ask him.

Officer: They should consult with Chittakotta member and then do it.

Villager [male]: That’s what, both chairman and member together did it.

Officer: We should ask member why they allotted four sites in the same place.

President: Then it will be an objection. That member is a relative of his. We should consult with three or four villagers [before allotting sites].

Villager [male]: Write that they should not allot any site to anyone without deciding in the gram sabha.

Villager [male]: How will you permit the construction of a new house?

Villager [male]: You should give it to the poor. You should not give it to others. You should allot it as per the president’s decision and by consulting three or four villagers. When we people get angry, we fight, and that leads to negative reaction. The poor [Lingayats] don’t get any site here.

President: A couple of days back I went elsewhere. [When I am absent] They will somehow adjust and make it theirs.

Elite stewards asked questions that reflected sophisticated knowledge of funding and technical details of public works. The discussion recorded as follows about a bore well and water supply reflects the main speaker’s knowledge of the depth to which a bore well had been dug and his awareness of water tests and cost estimates related to the project’s implementation:

Villager [male]: Then, in Jala Nigama, you should build a water tank and arrange for the water facility.

Villager [male]: Tell in detail about how much is there in Jala Nigama.

Secretary: …Then for that you need to reestimate. We need to request the DGM. He has sent an order, and instead of plastic pipe they have put the estimate for iron pipes. According to them an assistant engineer has made the estimate. If the committee people visit the DGM, they will give us permission to start the work. It got delayed because of the iron pipe issue only. And one more thing, the bore well was a failure there. We need to have another bore now. But when it rained in September last year, automatically there was water, so it got blocked. Same thing will happen in case of the pipeline because of the water pressure.

Villager [male]: It [water from bore well] is not good for drinking. We need to put one more [bore] where they have shown one more point.

Villager [male]: Has the test been done?

Secretary: Already done. Because there was lot of fluoride content in that water it was unfit to drink. Here [new place shown for digging bore well] it is fit.

Villager [male]: If anyone drinks it, we will get to know whether it is fit, or, if there is sweet water in the other bore that it is good for drinking.

Villager [male]: We need to send an estimate for it.

…

Secretary: … One more thing. Earlier it was plastic pipes, now iron pipes will be used. There is a difference in rate. So it is better to take permission again.

…

Villager [male]: What our people do is they will kick one god and they will bless another god! One needs to sit quietly and another person needs to get it sanctioned. Do whatever you want, but it needs to benefit us. Put whatever you want, plastic pipe or iron pipe, put another Rs. 20,000 tax and get it done in this place.

Secretary: Even you know sir, that it is a government work.

Villager [male]: Stop it I say! We know it is government work. It is teamwork. There is no water in our bore. They spent one lakh to put that, but they won’t do the necessary work. If three meters more depth was put, we might have had water. It is in front of us now. Unnecessarily they dug a hundred feet bore well. You might have put iron pipes. They will work on their own, and they won’t discuss with others!

Overall, the most notable pattern in gram sabhas in low-literacy villages was the polarized nature of discourse between elite stewards and the others. This finding is a community-level analogue to a point made by Basu and Foster (Reference Basu and Foster2001) on the positive externalities associated with literacy at the household level. They argue that individual-level illiteracy matters less than whether the individual belongs to a household with at least one literate person. This is because the illiterate person can be guided by a literate relative to achieve a higher level of capability. We find, similarly, that in low-literacy villages in higher-capacity state contexts, more literate individuals can lead discussions in the gram sabha. This can compensate for the challenges arising from low levels of average literacy.

Medium-Literacy Gram Sabhas

Gram sabhas in medium-literacy villages showed considerable variation in attendance, quality of deliberation, and number of disruptions that occurred in them. Two of the meetings were attended by so few villagers that they were reduced to being merely informational reports by current government officials. Another was extremely fractious, with the ex-president dominating the discussion, using it as an opportunity to castigate current and past panchayat regimes. A few heavily attended meetings were devoted solely to distributing ration cards for subsidized food. These meetings were invariably made acrimonious by villagers clamoring to be included on the beneficiaries list. Verbal clashes regarding the allocation of funds among caste groups occurred in several of the meetings. Other meetings were quite deliberative in spirit. There were concrete discussions concerning various facilities required by the village, public works to be completed, and criticism regarding the quality of public works projects. Overall, a substantial number of these meetings had deliberative moments even though these were often interspersed with verbal altercations that could descend into chaotic and angry disarray. The stridency of exchanges in medium-literate gram sabhas was notable and exceeded that in low-literacy gram sabhas. We ascribe this to the likely equalization of voice attributable to higher literacy.

Articulating Demands

Competition among caste groups for development funds allocated by the state is a common feature running through several of the gram sabhas in medium-literacy villages in Bidar. Villagers showed greater awareness of the principles used by the state to allocate funds and were keen to question these principles. In the following excerpt, villagers ask pointed questions about whether caste related allocations were based on population size or the caste affiliation of panchayat members. Persons from one caste group appeal for a larger share of the budgetary allocation for laying concrete roads, complaining that their village has been neglected:

Joint engineer: In that 50% is for general [castes] and 50% for SC-ST. They will give half to general and half to SC-ST. It will be different budget for different works. Nobody should raise any word against SC-ST share. It is almost one lakh. And add to that the share for STs and in that you can get any work done as you want. It is totally for SC-ST. Each member will get Rs. 8,900.

Villager [male]: Sir, how will you divide this money? And is it on the basis of the number of [ward] members or population size?

Nodal officer: We divide on the basis of population.

…

Villager [male]: First gram panchayat budget is spent. Mr. Ashoka Patil has said this in the panchayat. At that time we gave it from our heart. It was a necessity for them. Now they don’t require it, so let them give it to us.

…

Villager [male]: We had given earlier, now we are asking. If you say no, how can it be [don’t refuse our request]!

Nodal officer: Let us see.

…

Villager [male]: Take Rs. 1,00,000 and form a cc road.

Villager [male]: Rs. 1,00,000, thank you for that! After telling so much we never got any money. Since five years we haven’t received anything. Now villagers requested president to do whatever you want, but develop Kotamala as you have developed Miracal. As you have cc road in your place, provide the same for us also.

Nodal officer: Without your consent we will not do anything.

Villager [male]: We are not talking like mad; we are not crazy!

Villager [male]: Yes, Raju, sit down.

Villager [male]: No sir, it can’t be like that. We want cc road.

Officer: Tell what other works you want?

Villager [male]: Let the work up to Rs. 1,00,000 be perfect.

Villager [male]: What amount of work can be done in Rs. 1,00,000! Everything is there in the government, but it will not do anything. We want roads at any cost. What can be done out of Rs. 1,00,000!

…

Villager [male]: We will not get the total amount. There is a separate budget for STs.

Villager [male]: How much is there for SC-ST?

Joint engineer: For SC-ST it is 78,000.

Villagers have the capacity to give their development needs deep consideration and the discursive ability to present compelling rational arguments to support their proposals. In the following excerpt, the demand for a road is quickly accompanied by the demand for a drainage canal to be built flanking the road on two sides. Villagers clarify that the canals are required to prevent sewage water from flowing onto the road. This will help in maintaining the road in good condition. Villagers insist that the cost estimates be clearly presented to them by the panchayat staff:

Villager [male]: CC road is there, no. Eight meters of cc can be done.

Secretary: It is approximately five to ten thousand, more or less that much. As we are not technical people we can’t tell perfectly.

Villager [male]: We need to have a canal.

Villager [male]: It should be sloped so that the flow of water will be easier.

Villager [male]: If it is not possible just leave it.

Villager [female]: We need to have a canal.

Villager [male]: If not canal, at least, let us have cc road.

Villager [male]: If it is not possible, you should look into the panchayat! Look at what is there legally. Whether you are there or we are there. If you do things legally, there will not be any problem. You have got all the rights to ask them. Say that you have got all the documents with you. Whatever you do, it should be within the budget limits.

…

Villager [male]: If canal work is done, then no vehicle can go there.

Villager [male]: No vehicle!

Villager [male]: Then we need to have a small canal.

Villager [male]: Yes. If it is left like that …

Villager [male]: Yes. It can’t [be left without constructing canals], for that only the cc road is like that [poor condition].

Villager [male]: Where there is less space we need to have a small canal there.

…

Villager [male]: From that direction water will flow.

Villager [male]: The rainwater will flow on the road.

Villager [male]: Let the rainwater go there. No problem. I am talking about drainage [sewage] water.

Secretary: Discuss, discuss. Whatever you tell we will write down the same.

…

Villager [male]: If you can put the pipe without touching the compound wall, it is OK. Do as per the specification.

Villager [male]: On whose doorway will it pass by?

Villager [male]: How many? May be that of ten houses. That is it.

…

Secretary: Do the work within the budget. We have got no say in that.

…

Member [male]: Listen here. Canals to be put on two sides. We will do however much is possible within this budget.

Articulations of demands in medium-literacy villages included competing claims on budgetary allocations made by the various caste groups. The caste-competition for government resources reflects greater political literacy about the rules and regulations governing panchayat finance allocation. There were instances of verbal conflict among villagers, but there was not a single instance of one group complaining about the unruly behavior of another, as was the case in some low-literacy gram sabhas in Bidar. We ascribe this to the existence of discursive parity in medium-literacy villages.

Seeking Accountability

Greater political literacy enabled villagers to hold officials accountable. Detailed knowledge of public projects underway was particularly helpful for this. The following excerpt records villagers exposing panchayat officials’ responsibility for the flawed construction of the childcare center. Using an admonishing tone, villagers denounce the panchayat secretary for the faulty construction plan and for paying off the contractor without first checking on the quality of the new construction:

Secretary: See, I will put forward the expenditure and income for our panchayath as a total for the year 2004–05. Expenses toward salaries of gram panchayath workers from March 2004 to March 2005 is Rs. 36,000. Royalty to the president is Rs. 6,000. Gram panchayath building costs Rs. 22,400, and the panchayath building is still half due.

Villager [male]: Which building?

Secretary: The one in Thogalur.

Villager [male]: Have you put pillars or not?

Villager [male]: Since they have put up a screen, we cannot see it.

…

Secretary: See, we have constructed according to the government’s estimate. We have constructed the pillar and foundation.

Villager [male]: How much did it cost?

Secretary: … See, the Anganwadi building costs Rs. 93,000.

Villager [male]: Since when did you receive the funds?

Secretary: For that one we got Rs. 93,500. See, our budget has to be utilized within March. That [money] is for paying the contractor of the building.

Villager [male]: Nobody will call that building an Anganwadi! That is called a room; that is all.

Secretary: What I am telling is …

Villager [male]: We don’t want it! Look at the work done.

Secretary: Yes, you are right, but you are talking about it after everything is done.

Villager [male]: Yes, you are asking now, and we are telling you now!

Secretary: There is still some pending work to be done in the building.

Villager [male]: Pending work?

Villager [male]: You might have given it to us.

Secretary: No, no, without the work being completed we can’t give it [open it for use] like that.

Villager [male]: You should not give. If the work is perfect then only you can give. But you will tell, that has to be done, this has to be done! …

Secretary: Look.

Villager [male]: We will not look, reply to us! Since the proposal was for two [pillars], how did it become one?

Villager [male]: Then they will search for the foundation! [Sarcastically implying that there is no foundation.]

Villager [male]: There were two, yes, two. But how come now there is only one?

Secretary: There were two.

Villager [male]: [With sarcasm] In which direction did it go?

Secretary: There was provision for two pillars in the plan. We were supposed to construct two.

Villager [male]: OK, is it perfect? No. There is no foundation at all.

Villager [male]: Next time, if the work is perfect then only clear the bill [for payment to contractor] or else don’t clear it. I am saying this not for my own sake. I am saying this on behalf of all the villagers.

Villager [male]: See, now it came out [the true facts were revealed]!

Villager [male]: Yes, he is right! If something goes wrong, we will raise an objection about you.

Secretary: It will not happen next time.

Villager [male]: Next time?

Secretary: I have a request to you all. Whatever work is going on, you people should keep vigilance on that.

Villager [male]: If [good] quality work is done, it will not be a problem.

Villager [male]: Did the joint engineer say to demolish and reconstruct the building or not?

Villager [male]: He went home.

Villager [male]: We should take some money and, as he proposed, demolish and reconstruct the building. I gave him [joint engineer] a piece of my mind!

Secretary: No, no, I will not tell whether it is done or not.

Villager [male]: Do you call it as a work if there is no foundation at all! You do the work properly. Whether you take some money [bribe] for that or not, we don’t mind. But we want good work to be done.

Secretary: What is going on here? Tell me whether the work is done or not. I want to report the same.

Villager [male]: No.

Secretary: If it is not perfect, I will cancel it.

Villager [male]: Joint engineer should see it. Only he can judge both the quantity and quality of work done. That is his work. Nobody else can do it.

Secretary: For this we need to call the joint engineer.

Villager [male]: Call him, call him.

Secretary: Call him.

Villager [male]: See, nobody will work properly. Call the joint engineer. We have no objection.

Secretary: See, I am telling in this gram sabha meeting …

Villager [male]: Whatever public money is there, it has to be utilized in a proper way. That is my main concern.

Villager [male]: We are asking about the money that is being misused.

Secretary: Ok.

Villager [male]: We need to have perfect work done.

Villager [male]: Even though one work is not done fully, how come we cleared both the bills?

…

Villager [male]: This should not happen in the future.

Medium-literacy gram sabhas displayed considerably less citizen polarization than low-literacy ones. In low-literacy gram sabhas, often a large group would engage in bitter verbal fighting, creating a cacophonous backdrop against which a smaller group of elite stewards sincerely tried to deliberate. They chided and guided other villagers in framing demands and conducting themselves properly in the gram sabha. In medium-literacy gram sabhas, many contrasting voices participated and were patiently listened to. Villagers who spoke in less articulate ways were not instructed or assisted by their better-educated counterparts. In villages in which literate citizens outnumbered illiterate ones, there seemed to be fewer civic incentives for the former to guide the latter in articulating their demands and framing complaints. We speculate that, beyond an initial threshold, literacy creates an atmosphere of relative discursive equality where everyone feels free and competent to voice their claims and complaints in their own discursive style without being checked or corrected. This can lead to deliberations being disrupted by fights and villagers speaking en masse. In both medium- and low-literacy settings, villagers were able to bring pressure on panchayat members to perform their duties better. In low-literacy villages, elite stewards were able to do so effectively while in medium-literacy villages, a greater number of villagers were able to hold officials accountable.

PAIR 3. DHARMAPURI, Tamil Nadu: 31 Low-Literacy Versus 14 Medium-Literacy Gram Sabhas

Political literacy in Dharmapuri was relatively high. Even in gram sabhas in low-literacy villages, citizens showed reasonable knowledge of panchayat functioning and were familiar with the protocols of public deliberation. In medium-literacy settings, citizens showed the skilled use of fine-grained information to strengthen demands and support comments while deliberating on matters of public interest. This minor difference aside, in both low- and medium-literacy settings in Dharmapuri it can be said that citizens acted as civic deliberators. They differed very little in their levels of political literacy.

Low-Literacy Gram Sabhas

In Dharmapuri, thirty-one of the gram sabhas were in low-literacy villages. Three distinctive patterns characterized these meetings. The most remarkable aspect was active vocal participation by women. Women were often the first ones to voice their grievances and demands, and they were no less articulate and assertive than their male counterparts. In six of these meetings, female attendance far outstripped that of men. Many of these women were members of self-help groups, or SHGs. This was evident from the demands they made. Generally, women raised issues related to their SHGs (building for the group, livelihoods) and drew attention to problems in the public distribution system (ration shop malpractice) and the inconveniences faced by children (lack of day-care centers, improper school facilities, and inadequate transportation to schools).

While articulating demands, villagers consistently framed problems by mentioning the history of past actions that had been taken to register or remedy the problem. This style of articulation was different from simply voicing problems. This discursive tactic was indicative of the relatively high level of political literacy among the villagers. Both women’s active verbal participation and the shared discursive strategy of framing demands were surprising given the low level of literacy.

Villagers transitioned seamlessly between voicing demands for public goods for their village and requesting personal goods and subsidies for their families and households. Villagers spoke with a tone both of entreaty and entitlement when making personal demands. Making requests at the gram sabha for personal needs reflected the state’s long history of political patronage. The two political parties that have held power over the last few decades have a strong history of providing free goods and subsidized schemes to the rural population.

Articulating Demands

It is typical of women belonging to SHGs to speak at these meetings. They were often the first citizens to voice their concerns. The following excerpt records a woman who belongs to an SHG voicing multiple demands. The follow-up question about the time frame for fulfilling these requests reflects an acute understanding of the cyclical nature of the electoral process. People recognize that the reliability of promises made in the gram sabha is hostage to its timing.

Mrs. Amudha [villager, OBC]: I am Amudha. There is a self-help group in Kondappanayanapalli. It started long back. There are ten self-help groups in total. But even then there is no common space for those self-help groups [to meet]. We meet and work under somebody’s roof or under trees. In each gram sabha meeting we keep saying about this. But no action has been taken. Then in our villages since agriculture is shrinking, if poor ladies get any opportunity to work, we will send our children to study and maintain our families happily. Since we are unable to educate them, they are all simply sitting in the house and we are suffering a lot. So, kindly, please make some arrangements for it.

Panchayat clerk: In this village, currently we are arranging to construct a building for the self-help groups. It has already been promised in the earlier meeting.

Mrs. Amudha [villager, OBC]: Will you do in the short term or long term? Since he (panchayat president) will be in the administration for only some more days (i.e. be in power till the next election cycle), within that he must do. He has said this in many meetings. So I request them to do it in the short term.

Demands for public resources led to lengthy discussions marked by cogent practical reasoning. The following excerpt records a deliberative discussion regarding a water shortage in which women voice their complaints in an authoritative and aggressive manner. Villagers, ward members, and panchayat officials all put forward consistently argued reasons supporting their actions. They even appear to reach consensus on the remedial actions to be taken. In this excerpt a pattern often observed in gram sabhas is played out: panchayat officials and the public reach a decision through what seems on the surface to be a hostile deliberative process:

Mrs. Akila [villager, Muslim]: My name is Akila. I don’t hold any post; I am a housewife. We have given lots of petitions to the village panchayat administrative office, to the collector, etc., but for this Pattakapatti they have not done anything. Why have you not taken any action? If you don’t take action within three days we don’t know what will happen! [Possibly threatening agitation.] You tell us whether you intend to do anything or not. [Talks angrily.]

President: You have the right to ask so you can ask, but you must not talk like this, “we don’t know what will happen if we don’t get water within three days.” Government work will progress slowly only.

Mrs. Akila [villager, Muslim]: We have told the same [panchayat] head, but what did he do?

Villager [male]: In our place alone there is no work or no improvement done.

Villager [male]: We are not asking for anything except drinking water. Even if we go to different villages, they don’t give us water. Our fasting days [Ramzan/Ramadan observed by Muslims] have come; let us at least have drinking water. We are not asking for road facility, toilet facility, etc. We don’t have any other facility.

Villager [male]: For this place you have not done anything. What have you done for this place? Have you given road facility, toilet facility, etc.? Why must I talk softly? What’ve you really done for our place? [Shouting angrily]

Union councilor: In our village we have six [water] tanks. You are asking what we have done! Just because a Muslim person’s house caught on fire, we have spent Rs. 64,000 on houses. Just for a single person.

Villager [male]: Is that the only thing needed? We are asking only for water facility. In your place school is there, toilet facility is there, everything is there. But what’ve you done for our place?

Mrs. Akila [villager, Muslim]: Shall we take a jar of water from your house? [In anguish]

Union councilor: Each year they give money for one village. It cannot be given to all the villages at the same time.

Villager [male, SC]: Even while casting our votes we asked for drinking water facility. Are we asking for road, light, and other facilities!

Union councilor: We have dug two bores spending Rs. 35,000 each.

Mrs. Akila [villager, Muslim]: Where is the bore for us?

Villager [male, SC]: There is no water in the bore. If water were available in the bore, we would not need to go in search of water to other villages.

Union councilor: Entire India is suffering without water due to the failure of monsoons, so what can we do!

Ward member: We want that to be done immediately. In the first month itself the coil [of motorized water pump] was burnt, so we told our head to take action. He said we have to give petition to the collector. We ourselves gave petition to the collector. He ordered to dig 500 feet bore. On the fifth month and ninth day, on the eve of the election, our head said we can use the same motor. But since the horsepower was less, it could not suck water from even 170 feet depth well previously. The coil is under repair three to four times a year.

Union councilor: We even tried our level best by laying pipes by spending Rs. 20,000. But your ward member refused to accept that and was adamant about getting a new motor. He stopped the process of laying pipes. Your member said so. He asked us not to fix the old motor.

Villager [male]: Who said so?

Union councilor: Babu, ward member. He said we need new motor to be installed; we do not want the old motor.

…

Villager [male]: It is six months since the pipes have arrived here. [All of them shout in unison angrily.] Why must we be quiet? You listen to us!

Union councilor: Just listen to me and then talk! Only after doing the whole job like fixing up pipes and fixing the [old] motor, then run it, and finally if you still do not get water only then can you question the panchayat board. If the motor does not have the HP [horsepower] and you don’t get water, only then you can complain. You all told either you put new motor or don’t put anything at all. After laying pipes and fixing the motor, if you don’t get water you can ask me. Panchayat does not have fund for installing a new motor. But if the old motor does not work then definitely we would do the needful to get a new motor. All of you stopped the work even for laying pipes.

Villager [male]: You said men are stopping you. I’ll tell them not to stop the work.

Union councilor: What is the dispute between us? Why must we fight with you all?

…

Union councilor: As the member says, if this is fixed, all the illegal [water] connections must be cut [disconnected] in each house.

…

Union councilor: We can fix the motor within eight days. Without my permission they have drawn [household water] connections.

[All talk together …]

President: We’ll install a new motor, but all the illegal connections must be removed. Not even one connection must be there.

Union councilor: We will install ten taps at the center of the village in a row, and we will install a new motor, but not even one illegal connection must be there in the village. Everything must be cut.

Villagers in low-literacy settings used gram sabha meetings to report and attempt to remedy people’s unauthorized activities in the village. Their complaints reflected their knowledge of rules and regulations governing the use of common property, including land and trees. We take this as indicative of a relatively high level of political literacy. The following excerpt records villagers listing activities occurring in the village that infringe upon rules. Speakers request that the panchayat take action against those individuals who are abusing villagers’ rights to common use of public property:

Villager [male, SC]: I am Sathyamurthy. In our village, in school lands around thirty persons have constructed houses. That place is meant for school and panchayat. The government has to take action to remove the houses. They have to be demolished.

Villager [male]: Remove houses that are in the place of the temple.

President: We will speak regarding this to the government.

Villager [male, SC]: In my village, there are three houses on temple lands. Even after getting judgment from the court, three private people are using it as their own land and they have built house on it too. Also they have not submitted the income regarding this to the government. So what action are you are going to take regarding this? Private people are using that as their own place. We have given requisition letter to the minister and it will be certified. Councilor and other leaders have given a request letter to the concerned department but even then, till now no action has been taken. It is not been rectified yet. Then in the lake of Ellanathanoor village, since private people are doing cultivation, no one else can do farming as there is no water in the lake. Government should take action against them and get the lake areas from them and hand it over to the respective persons. This problem has been handed over to the respective minister. The lake areas have been marked separately and shown to the concerned government officer. But till now no action has been taken.

… .

Villager [male, OBC]: Private people have cut the Karuvelam trees (used for fuel wood) and used it for many purposes. This is a great loss for the government. If it’s auctioned and handed over to the government, it will be of great use for them. Lots of trees have been spoiled. All are being looted. There has been a loss of around one lakh for the government.

In the political culture of Tamil Nadu, it is common for citizens to make personal requests for welfare subsidies. Some adopt a tone of entreaty, pleading for personal relief in the face of household crises. Others employ a tone of entitlement. They command assistance and criticize the government’s failure to attend to their individual needs. The following excerpt records one instance out of a myriad of possible examples.

Villager [male]: [This man was fully intoxicated and he was being noisy.] Since the past ten years the earlier president did nothing for us. This president – I will only tell the truth – all the municipal officials and Tahsildar all know about us. I have asked for a loan, and now they are refusing. I do not have anything. The government has to help me. It should do whatever it can for me. I have a son. I work hard; I have nothing. I ask the government to help me.

Villager [female]: I am Rani from Nallampatti village. I am a laborer in the fields. I do not own any farm. I request the government to help me. My husband is no more. I have come here to request for rice under my ration card. I want to give it in writing. The roads here are not proper.

In Tamil Nadu, making personal demands of this nature (houses, loans, food staples) does not indicate a lack of political literacy. Rather, it reflects a rational response to liberal welfare state provisions adopted by the leading political parties as a populist strategy for gaining advantage in electoral competition.

Even in low-literacy villages, men and women were acutely aware of public resource and infrastructure issues and had a good sense of the gram sabha and panchayat’s scope of action. They made forceful demands on the local government and, even when their verbal expressions were hostile, the content of their communication was articulately framed and persistently delivered. Their participation in deliberations was not received as unruly or disruptive.

Seeking Accountability

Villagers use gram sabhas to expose problems with public services and hold panchayat members accountable. They speak out against inefficiencies in the free noon meal program for children and the lack of fair prices for food and public transportation. In their search for accountability, villagers often try to negotiate with panchayat officials regarding sharing responsibilities for the upkeep of certain public resources. The following excerpt captures one such discussion. It includes a wide range of topics from citizens’ obligation to pay taxes to whether responsibility for maintaining village hygiene falls within the purview of the panchayat or resides with the public at large.

Villager [male]: I am Alagesan. There is no hygiene in the village. There are lots of sewage ponds in and around the village. The reason for cholera disease spreading over here is that there is no hygiene. They built one corporation toilet, but in front of that itself there is a sewage water pond. All the sewage water accumulates there. They have to remove all these ponds; only then the hygienic conditions of the place will improve. All the drains are clogged.

Block development officer [BDO]: Who closes these drains? You have to take care of your house and your street. You are selecting the leader and you are complaining about him. The village panchayat management is like a big kingdom. You have to take care of hygiene, and you should take care of removing garbage and other wastes. You are not cooperating while constructing buildings. Whenever a building is constructed for being used as toilets, you are not using it properly. Male population like us goes to toilets or urinals wherever we like, but this is not possible for the female population. Because of that we have constructed a toilet in the corner of the village. We have installed a bore pipe [water connection] there so that they would use it. Though we are not able to construct toilets for each and every house, we have constructed one in this place so that the ladies can use this. And, in time, bathrooms will be provided for them to take baths and wash their clothes. Then automatically the hygiene condition will improve.

Villager [male]: But the responsibility is with the leaders. There is a big sewage pond with dirty water in the outskirts of the village, which cannot be cleaned by one or two persons. The leaders should allocate funds and have it cleared.

BDO: There is nothing called fund for all those things! Village panchayat cannot do everything. We are collecting taxes, but with that amount how can we spend? When we get married, we should earn money to raise our children [indicating personal responsibility]. Do you know what are the electricity charges per month? You have to take responsibility for the management of the panchayat. You people do not allow us to increase the house tax. You people do not even pay the water tax. And you are asking us to install [electricity] bulbs in the streets!…

As evident from this excerpt, villagers forcefully press on the local government for services that they perceive the government should provide. The government official, meanwhile, instead of being casually dismissive, explains through simple analogies and technical details regarding panchayat revenues, why the panchayat is unable to provide all the services needed. This exchange captures a moment of informed public negotiation regarding service provision.

Medium-Literacy Gram Sabhas

Gram sabha deliberations in medium-literacy villages were similar to those in low-literacy ones, except that in the former villagers presented information that was even more detailed with specific numerical information and more pointed reason-giving in articulating their demands and grievances. They appeared to display a heightened awareness of the detailed procedures related to beneficiary selection, bureaucratic tasks, and practical decision-making responsibilities.

Articulating Demands

The three patterns that stood out in these gram sabhas were women’s active participation in registering their concerns (often through several participants’ serial statements, all emphasizing the same problems and demands); villagers’ ability to infuse their statements with appropriate factual information and strong public reasoning; and their detailed awareness of rules and requirements regarding the acquisition and improvement of public infrastructure. The following excerpts record these aspects of medium-literacy gram sabhas.

In the first example, a small number of women make a coordinated attempt to press for various demands. A woman SHG leader starts by laying out multiple demands. Two other women follow up echoing the same needs and add specific details on how to fix the transportation problem. Finally, the SHG leader speaks again, closing her speech with a critique of the current affirmative action policy. The level of coordination reveals considerable expertise in participating in gram sabha deliberations:

Ms. Latha [leader of Parasakthi self-help group, MBC]: I am Latha. I am a member of a self-help group; my place is Kattuseemanoor. I asked for a phone [connection] for my village from the telephone office. But they said that they don’t have the name of that place [in their database], and also that only I had come and asked for the phone and nobody else had come. But I filled up everything and they asked for Rs. 10,000 as deposit. Till now we don’t know anything about that … Our village has all the facilities. But now all places don’t have water. They say we won’t get water even if we dig a bore well. Even though our village has a bore, it gets repaired often. The bore can function properly only when a place has electricity. We asked for that also, but they have not provided a connection. And we asked for ration card facility for our village people. But still they created problems saying that they can’t do it for our village. All villages have bus facility. That facility also we don’t have. I finish with that.

Ms. Rani [villager, MBC]: I am V. Rani, Kattuseemanur ladies club. We all have water problem; often the bore gets repaired. Bore pipe should be repaired. We don’t have bore pipe.

Ms. Vijaya [villager, MBC]: I am C. Vijaya, Kattuseemanoor. In our village, we struggle a lot for water. Bore gets repaired often. We don’t get even a single pot of water for drinking. There are more than a hundred houses here. No one has a phone. So we need that facility. And we walk four to five kms for bringing ration [subsidized food grains] and we need to cross the lake. It’s very problematic. So we need a ration shop here. Young people are going to work and for studies. So they need bus facility to travel. Even when buses come, they don’t stop here; they pass by our village. So they come back to the house and it is a loss for us. [Bus number] 37, B5, B8, and all go this way. So we need these buses to stop here and take us. The school here is only till the eighth standard. I request you to bring a school for us. But nobody cared until now. So these are all the main necessities for us. Nobody takes care of it, even president and vice-president don’t care about it. So you have to take care. They don’t listen to us at all. They didn’t install lights for our village and bore also is not repaired. For how long can we ask? That’s all.

…

Ms Latha: I finish this speech with thanks. Only SCs have all the facilities. But BCs [backward castes] don’t have any facilities. Even to build a bathroom they have to get permission from the sangham leader. So kindly arrange for funds for BCs also and for all the facilities too. Please get the roads repaired and also arrange to get Suzhal Nidhi [government project]. We are unable to build a sangham too.

Discussions about public goods ran longer in medium-literacy gram sabha meetings. Arguments were based on factual knowledge as well as on justice concerns. The following excerpt is taken from an extensive discussion on road conditions and water stagnation, lack of bus connectivity, and the associated problem of children not being able to get to school. The female speaker provides detailed information to bolster her case and offers compelling publicly minded reasons to support redressing the problems she identifies. Her comments reveal her knowledge of the complicated process for inviting tenders for public works projects like road construction.

Ms. Murugammal [villager, BC]: My name is Murugammal, Kattakaram panchayat, Mudalniahi self-help group. In school three children have fallen down. It is very slippery and there is a lot of mud during the rains. The stagnant water reaches up to our legs. Last time we reported about this and asked to have it cleared, but nobody took action and simply went off. Then in ten roads, many thorns are there.

Buses are not coming for the past four days. So teachers are all coming by walking from Kanakoti. They feel it is difficult and say that they won’t come. Children also cannot come. In the evenings also buses are not running properly. So we have to walk till Annanagar. Or else, if we miss that, we have to go to Anakodi. So we don’t have any facilities. You all say that you are doing, but nothing has been done. Teachers also fall in that mud. Even councilors and leaders don’t care about this and take no action. So you have to answer for this. Do you feel there shouldn’t be any school in Kattakaram? What else can we do?

They have informed that they will put new roads. But till now, the letter has not come. Since tender has not come, they are clearing those thorns for the past two days. They are working. For putting roads we must get tender. Sand should be put before the school definitely over there because buses are not coming and children also feel it is hard to come. Lessons also can’t be taught even a single day. There is no way to go and also no place to cook food [school midday meal]. You can see. Then how will the people survive?

There is no way for the water to go. Sand should be put there. You said that it will be done within days. But till now it hasn’t been done. Two months have gone by. They said tar road has been sanctioned. It’s very problematic. Buses should be able to come at least twice, in the morning while going to school and evening while getting back. If the children miss the bus, they return home since they take time to walk. So they put absent for one day in school. Again, the same problem is repeated the next day also. So for four to five days the buses have not been running properly. In case of emergencies it’s very problematic. Some have bicycles and they go by that, but most of them depend on the bus. So they can’t go to places that are further away. So we need bus facility definitely. That’s very important. We can’t expect bus anytime … Or else school will be stopped in Kattakaram … The place will not be developed in any respect. The panchayat will get a name [good reputation], so you have to take care of these. We too will cooperate for that. You itself come directly to see. In today’s position, you itself come and see it.

The relatively higher level of political literacy was evident in discussions about resources like household water connections and bore wells, where villagers showed their awareness of rules and requirements. The following excerpt records villagers strongly urging the panchayat president to take action against violators and non-payers and explaining the rationale behind the government charging villagers a deposit for bringing workers and instruments to the village for getting a bore well dug:

Villager [male, MBC]: Water is not coming at all and that is why we have removed the taps. Since you are giving water to their houses they are not bothered.

President: You only have to replace the taps that are near your house.

Villager [male, SC]: Cut the supply of water to individual houses and make them fill water from the common water tank. Why should we collect water from a tap near our house instead of coming and collecting it from the common tank? We have to convene a meeting and tell people about how to save water and use it economically. When you open the tap, immediately they put the motor to fill water in their [household] tanks. So how can we get water! If you cut water they will spend it economically.

…

Villager: They have to pay a deposit of Rs. 1000. There is a booklet for it. If they have any problems let them come and rectify it in the panchayat. They have to pay a monthly fee of Rs. 30. If they don’t pay, we have to cut their taps with EC. We can tell them and if they don’t listen, we can cut their water connection with the help of the police. Even if somebody asks for household water connection, we need not give it. Only if they pay a deposit of Rs. 1000 rupees and a monthly fee of Rs. 30 to the panchayat, acceptance must be given to them. If they don’t pay, connection must not be given to them. Even if they deposit Rs. 1000, the connection must be given in the presence of either the town panchayat head or town panchayat ward member or a person working in the town panchayat. The connection must not be taken without the knowledge of the panchayat. These things must be discussed in the meeting, and if they don’t agree to this their water connection must be cut.

President: OK we’ll do that.

Villager [male, MBC]: They collect the water by diverting it when it is coming in the main line itself and we don’t get water here. They are using it twenty-four hours. We get only what is remaining. From here it goes to Vedunelli and it is not sufficient for everybody. If it goes to Vedunelli, we don’t get water. So if we remove the tap we can get some water. Either you put a gate valve and regularize the water flow or cut the main gate valve. Or else drill a bore well and change this situation.