Book contents

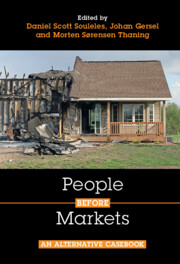

- People Before Markets

- People Before Markets

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contents by Topic

- Authors

- 1 Introduction: Why Are You Here?

- 2 Some Philosophical Help with “Neoliberalism”

- Part I Our World

- 3 Where Should Food Come From?

- 4 Where Should Water Come From?

- 5 Who Gets to Own Land?

- 6 How Should Food be Produced?

- 7 Who Decides Where They Live?

- 8 How Much Land Do We Need?

- 9 Where Should We Park?

- 10 How Should We Deal with Climate Change?

- 11 How Should We Make an Impact?

- Part II Our Lives

- Part III Our Work

- Index

- References

11 - How Should We Make an Impact?

from Part I - Our World

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2022

- People Before Markets

- People Before Markets

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contents by Topic

- Authors

- 1 Introduction: Why Are You Here?

- 2 Some Philosophical Help with “Neoliberalism”

- Part I Our World

- 3 Where Should Food Come From?

- 4 Where Should Water Come From?

- 5 Who Gets to Own Land?

- 6 How Should Food be Produced?

- 7 Who Decides Where They Live?

- 8 How Much Land Do We Need?

- 9 Where Should We Park?

- 10 How Should We Deal with Climate Change?

- 11 How Should We Make an Impact?

- Part II Our Lives

- Part III Our Work

- Index

- References

Summary

Sustainability has become the privileged way businesses, NGOs, and governments think about actions they might take to remediate environmental problems and be good actors vis-à-vis natural resources and our shared climate. In turn, the way that sustainable actions are accounted for is in the language of “impacts” in which various accounting schemes seek to tabulate and communicate the degree to which some sustainable action has an effect in the world. The purpose of generating a quantifiable, representable impact is so that consumers might decide that it makes a company or product more worthwhile and more deserving of a consumer’s money on a market. On a market, a consumer has the ability to decide that other qualities (price, brand, convenience, etc.) could potentially outweigh good environmental action. The purpose of explaining all this is to show just how limited a utilitarian approach (one in which goods are measured, weighed, and seen as interchangeable) to fixing environmental problems is. What Archer demonstrates is that by tracking environmental action in terms of comparable, fungible impacts, one allows corporate actors to count their pollution or bad action, and continue to do it anyway, both masking it behind impact measures and abdicating any final responsibility to consumers. At the close of the paper, Archer offers a different way of thinking about sustainable environmental action, one that draws on various strands of indigenous thinking to illustrate what it would look like and how much more effective things would be if we understood good environmental action in terms of nonnegotiable values (in philosophy language, a “deontological” approach).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- People before MarketsAn Alternative Casebook, pp. 204 - 220Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022