An Historiographical Introduction to the World of Philip IV

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 February 2024

Summary

Decline, decadence, crisis, stagnation, and adversity are terms powerfully associated with the reign of Spain's Planet King; sombre tones that contrast sharply with the glittering cultural and artistic achievements (enhanced by his patronage) that led the period to be dubbed ‘the’ Golden Age, a label consciously competing with France's later Grand Siècle. Much work still needs to be done, as Alistair Malcolm notes in the opening chapter of this volume, to bring Philip IV into focus and out from beneath the shadow of his great favourite [privado], the Count-Duke of Olivares, whose first modern biographer, Adolfo Castro used an eighteenth-century French picaresque novel, L’Histoire de Gil Blas de Santillane, as an historical source; believing that its author, Alain-René Le Sage, had plagiarised it from a manuscript by the privado's confidant, Francisco de Rioja. Picaresque overtones are also on display in the widely known popular representation of Philip IV in Imanol Uribe's 1991 satirical comedy film El Rey pasmado [The Dumbfounded King], based on Gonzalo Torrente Ballester's 1989 historical novel and winner of eight Goyas, which similarly reflects persistent ideas rooted in the Black Legend about a frivolous, lascivious monarch hemmed in by superstitious religiosity. It light-heartedly sends up the absurd, overzealous moralising of ecclesiastics, whose interference in every detail of private life includes answering the question as to whether it is licit for the king to see the queen naked, a desire stimulated by his enjoyment of a rear view of the prostitute Marfisa in a tableau, at the outset of the film, that reproduces Velázquez’s ‘Venus of the Mirror’. While a junta of theologians give serious consideration to this question, people gossip and the king contemplates paintings of naked goddesses in the royal collection, locked away in a secret apartment. The king is represented in the film as ingenuous and innocent, while the film’s critique mocks the oppressive policing of sexual desire, reflecting its moment of production more than a historical reality.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

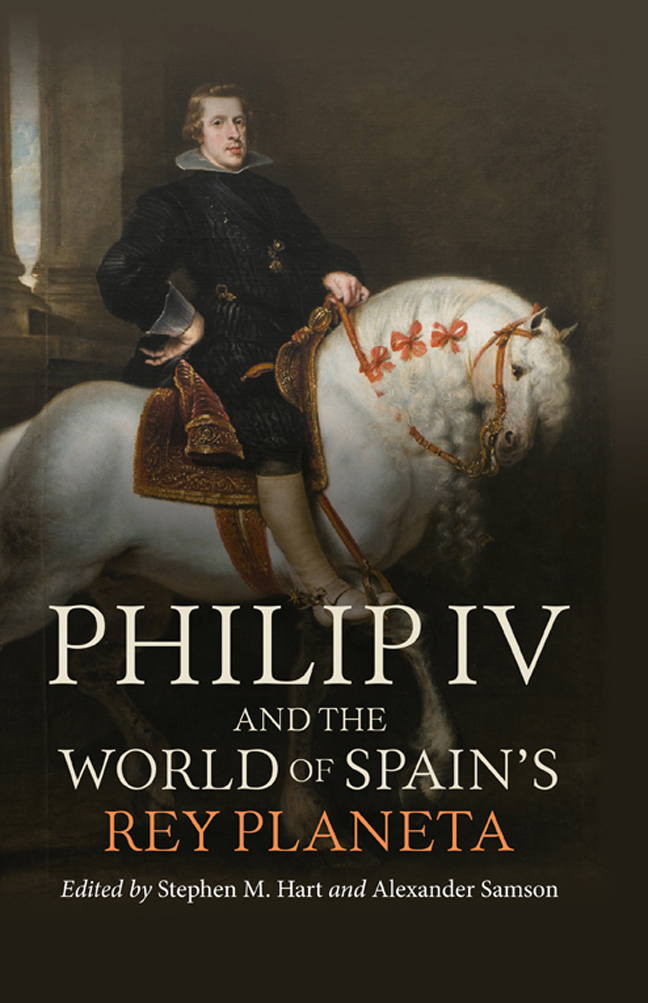

- Philip IV and the World of Spain's Rey Planeta , pp. 1 - 26Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023