The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global Visualization

The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global Visualization Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2024

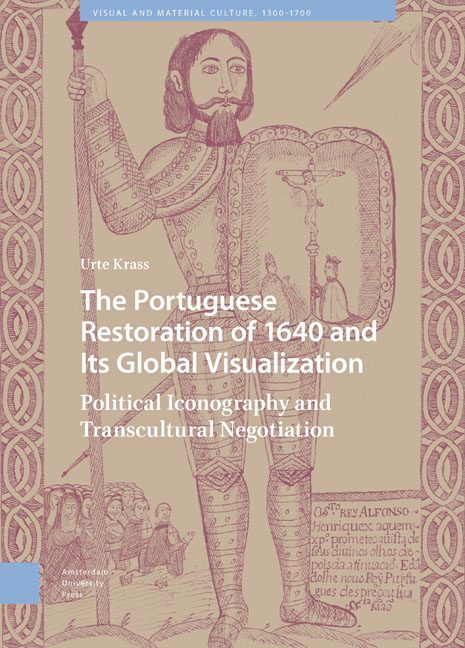

Abstract: A painting in the Lisbon monastery of Madre de Deus shows how the iconography of the good shepherd on the mountain, which had originated in Goa, had a lasting effect on other pictorial worlds: the figure of Saint Francis becomes a vehicle through which the iconography of the first Portuguese king can be combined in a novel way with the Brigantine iconography of the sleeping ruler of peace on the rock. A summary draws together the book's different threads and provides an overview of the different functions of the heterogeneous images and visualizations. The global interconnections of the images are outlined and an attempt is made to explain why the most detailed visualizations were created in the regions that were furthest from the site of the coup d’état.

Keywords: Madre de Deus convent in Lisbon, St. Francis, entanglements, distance

Today, in Lisbon's Madre de Deus church, visitors find a painting by Bento Coelho da Silveira, created in 1650. It is part of a cycle of images devoted to the lives of Saints Francis and Clara (fig. 184). The work depicts the dream of St. Francis, but not as presented in the saint's hagiography. In the vita accounts, the young Francis is still engaged in worldly things and dreams of a palace full of weapons and armor. In the midst of the vision, he hears a voice instructing him to abandon his military aspirations. In another episode in the saint's life, a crucifix summons Francis to renovate the dilapidated church.

In Coelho's painting, the dream vision of an armament-filled palace is combined with the Miracle of the Crucifix. As we have seen, this combination was widely promulgated in mid-seventeenth-century Portugal in another context: that of the Vision of Ourique, part and parcel of Portugal's founding mythology (figs. 77, 127–30). We find the discarded weapons in the left foreground, and there as well is a crucifix looking down upon the narrative's protagonist. The representation of St. Francis is thus linked interpictorially with the iconography of Portuguese political providentialism; or, in other words, the Portuguese Restoration's image worlds encroach on other pictorial themes.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure no-reply@cambridge.org is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle.

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive.