Durban’s ‘traditional’ schools – or, as some called them, ‘larney’ (fancy) schools – are situated on the Berea ridge, a residential area rising 500 feet from the city centre, with commanding views of the Indian Ocean, harbour, and the Bluff headland.1 In 1958, despite the ascent of Afrikaner nationalists into political power, it was still said of Durban High School, the city’s oldest school, that one would find its English-speaking old boys ‘entrenched everywhere that counts – in politics, industry, banking, the arts, diplomacy, the learned professions’.2 As in other colonial settings, South Africa’s top schools looked up to British private schools, from which many of their first teachers had been recruited.

In addition to Berea schools, this chapter foregrounds a new breed of working-class English- and Afrikaans-medium schools as well as their south Durban suburbs. Rob Donkin, in his autobiography A Bluff Scruff Miracle, describes the pride Bluff residents feel for their white working-class suburb: ‘One needed to earn the right to be known as “rough and tough Bluff scruff”,’ he says. ‘It was a title to be proud of and was a sought-after and feared reputation, especially by the “town clowns”.’3

While the origin of the idiom ‘rough and tough and from the Bluff’ is difficult to determine, some people link it to the hierarchical organisation of schools in the city. A former school principal, Mr Smit, who grew up on the Bluff in the 1950s referred to the building of three new high schools on the Bluff when explaining the phrase. Reflecting a view I heard from others of his generation, he said, ‘You had these elites and, ja, they looked down on the people of the Bluff … The old traditional schools, I think they will look down, you know, on the others.’ The dividing of suburbs by class created a strong sense of local community, and marriage between Afrikaans and English speakers in working-class areas such as the Bluff became relatively common.

Little has been written about hierarchies among white schools and white suburbs, a major theme in this chapter. However, these were central to the period of racial modernism instigated by the election of the apartheid government, which this chapter also introduces. The rapid expansion of white education in class-defined suburbs in the 1950s and 1960s necessitated an end to the intermingling of poorer whites and black people in cities. Segregated schooling worked to normalise the assigning of a ‘race’ to every South African and thus hardened borders between groups who came to be called ‘white’, ‘African’, ‘Indian’, and ‘Coloured’.

These differences in whiteness, and among white people, were also formative of the reform period from the 1970s, as we shall see later in this book. Moreover, the trajectory of public schooling desegregation from the 1990s rested on two key aspects of racial modernism: the spatiality of schooling hierarchies and the gendered cultural signifiers of class, including sports. By the 2000s, some schools were throwing thousands of rand at rugby scholarships to promote their whiteness, and soccer lost its appeal. Eventually, many white Bluffites ‘up-classed’ by sending their children to Berea’s schools – ones that historically had shunned learners from working-class areas.

This chapter begins by showing how the 1950 Group Areas Act removed black residents from ‘white’ areas and redrew the city’s schooling geography. To highlight the significant differences among white areas it focuses on the Berea and the more working-class Bluff areas. The next section outlines the work and training advantages provided to white people, including Afrikaans speakers, and the ‘insider and outsider’ status of Indian workers. Finally, we look briefly at differences between boys’ and girls’ schools. Table 2.1 summarises the schooling and spatial hierarchies discussed in this chapter.

| Dominant schooling type | Subordinate schooling type | How hierarchy was instituted |

|---|---|---|

| Berea’s traditional schools | Schools in working-class/lower-middle-class south Durban | The former followed an academic curriculum and showcased the national sport of rugby; the latter’s curriculum stressed practical skills, and students often preferred soccer to rugby. |

| English schools | Afrikaans schools | Highly contested under apartheid, but English was more dominant (especially in Natal) in business and professional jobs. |

| Boys’ schools | Girls’ schools | The former benefited from the power of old boys’ networks, and masculinities that position men as leaders in society. |

| White schools | Black schools | The former benefited from massive funding advantages. Schooling for black Africans expanded at the primary-school level, and for Indians at all levels. |

Schooling and the making of the apartheid city

The global rise of publicly funded schools is entwined with the establishment of nation states both in the West and in its colonies. The particular influence of English-language education is rooted in the British Empire’s control over nearly one-quarter of the world’s population in the early twentieth century.

On the southern tip of Africa – a continent imperialist Cecil John Rhodes famously wanted to connect from ‘Cape to Cairo’ – Britain granted dominion status to South Africa in 1910. This followed Britain’s military defeat of Afrikaners/Boers, a group predominantly of Dutch descent, in the 1899–1902 Anglo-Boer War. The formation of the Union of South Africa necessitated the amalgamation of the British colonies of Natal and the Cape and two former Boer republics.

A single public education system was vital to bringing together English- and Dutch/Afrikaans-speaking whites in the new nation; public expenditure on schools increased fivefold in the country’s first 20 years.4 The top schools fashioned an Anglophone elite, but education also aimed to uplift a group of ‘poor whites’, mostly Afrikaans speakers, whose existence was ‘anomalous and unacceptable’ to white society.5

After 1948, the apartheid government continued its support for white schooling but positioned race at the centre of a more ambitious plan for social order. Following its surprise election victory, the National Party, led by D. F. Malan, passed a slew of new legislation. The 1950 Population Registration Act created a register of every South African’s ‘race’; the 1949 Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act and 1950 Immorality Amendment Act outlawed sexual intimacy and marriages between white people and people of other races; the 1952 Black (Natives) Laws Amendment Act extended urban influx (pass law) controls to African women; and, as we will see in Chapter 3, the 1953 Bantu Education Act instituted an inferior public education system for African people.

It was the 1950 Group Areas Act, however, that transformed the racial cartography of South African cities. Urbanisation up to this point was often unplanned, as signified by the growth of racially mixed areas. In Durban, the Act resulted in the removal of an estimated 75,000 Indians and 81,000 Africans; this was more than 50 per cent of the city’s total number of Indians and 60 per cent of Africans.6 New black townships such as Umlazi were built on the edges of all cities. Whites, who made up 19 per cent of the country’s population in 1960, remained largely unaffected by removals, or became beneficiaries of cheaper land.7

Intensified racial segregation had another profound legacy: it helped make apartheid’s four racial categories ordinary and lived – in intimate interactions, identities, acts of oppression, and forms of resistance. The houses and schools built for ‘whites’, ‘Indians’, ‘Coloureds’, and ‘Africans’ gave these categories a solidity that persists to this day.

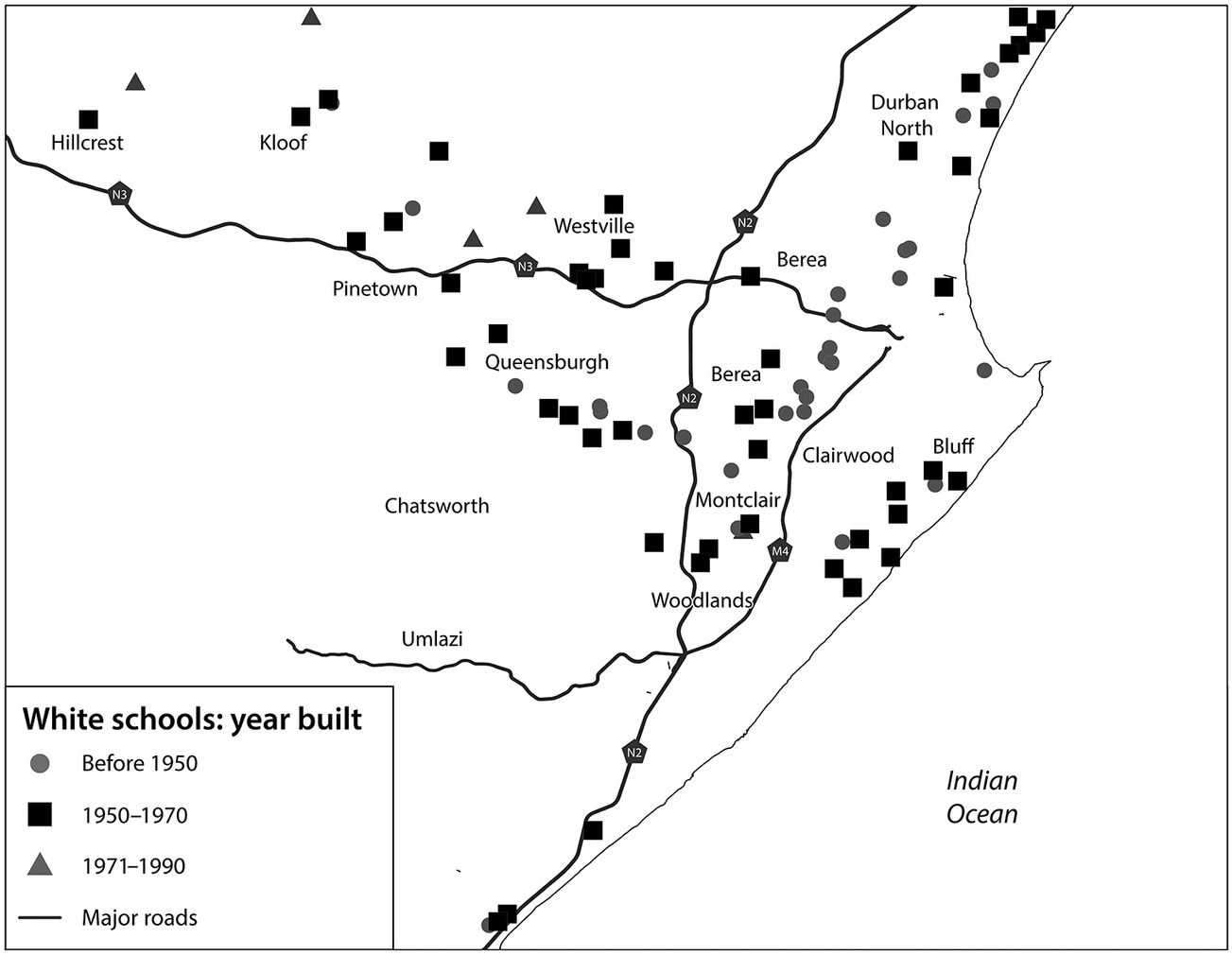

As such, urban schooling was not just cast in the mould of apartheid but formative of apartheid. For those classified as white, the removal of black residents – together with suburbanisation and the expansion of secondary education – stretched the schooling system outwards spatially. Finances came pouring in to the white education system: from 1950 to 1970, funding per white student increased by a factor of two and a half on the back of an economy that ‘never had it so good’.8 During this time, 50 new primary and secondary schools were built in new or growing white suburbs, including on the Bluff, Woodlands, and Montclair (to the south of the central business district (CBD)); Westville and Kloof (to the west); and Durban North (to the north). Indeed, by dating the establishment of white schools, we can track the growth of Durban’s familiar inverted T shape serviced by the N3 (east–west) and M4 and N2 (north–south) highways (see Map 2.1).

Map 2.1 Durban’s white schools by the year that they were built.

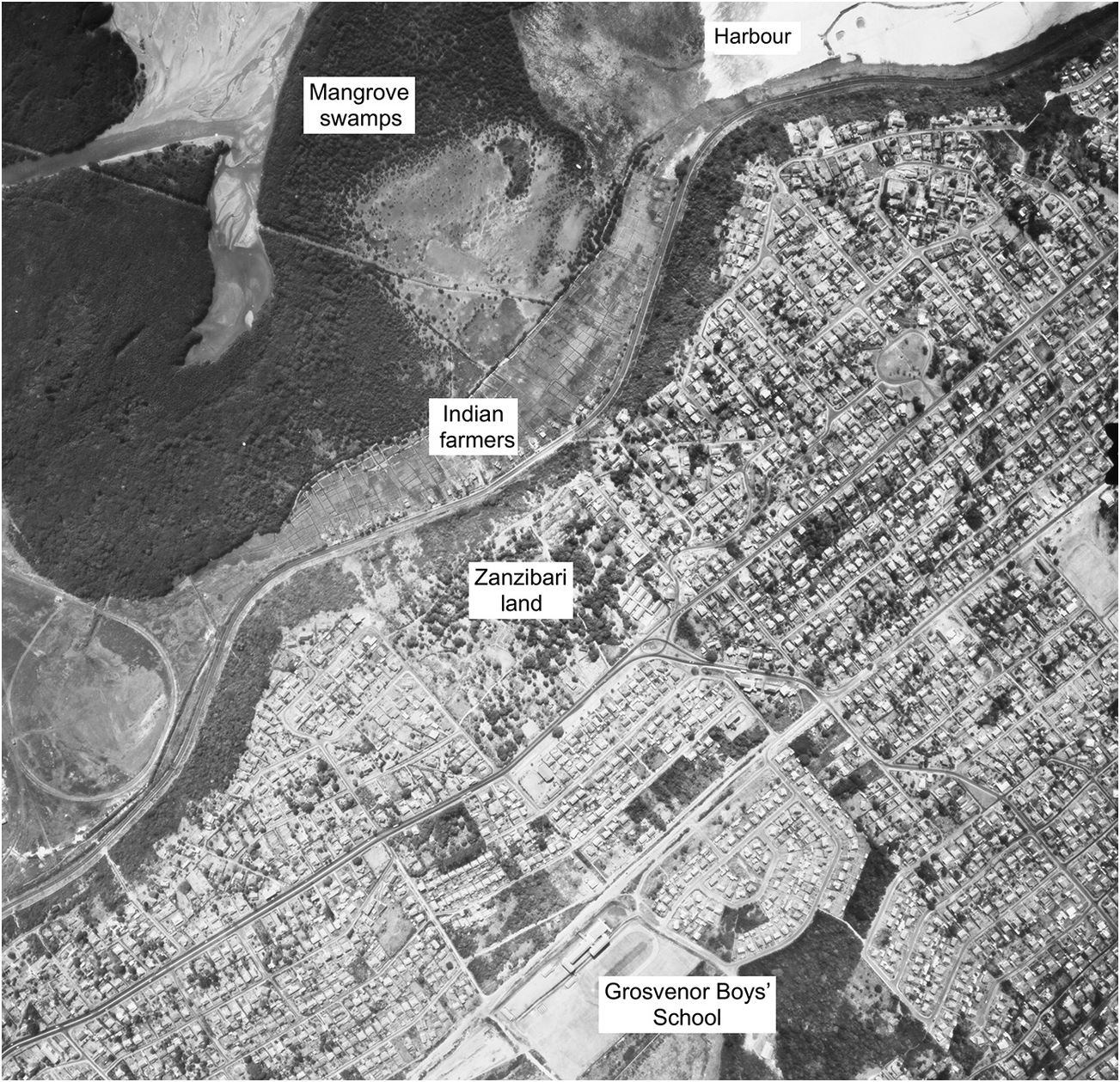

Durban’s southern suburbs, a major area of white schooling expansion, saw substantial Group Areas Act removals, second in the city only to Cato Manor/Umkhumbane located west of Berea. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, thousands of ‘Indian’ market farmers, most of them descendants of indentured sugar-cane labourers, had rented or bought land in south Durban. Many lived in wood and iron structures and grew fruits and vegetables for the city. Around 400 Indian people lived in a 90-year-old fishing village at the Fynnlands part of the Bluff, and a ‘Zanzibari’ community, discussed below, lived off Bluff Road.9 Significant clusters of ‘African’ shack dwellers resided in Bayhead near the port and Happy Valley to the south.10

Yet mixed-race spaces were anathema to the Group Areas Act – live-in servants notwithstanding. The northern part of the Bluff was zoned as white, Merebank and Chatsworth townships were built for Indians, and Wentworth township was built for Coloureds. The biggest area to resist removals in south Durban was the predominantly Indian business area of Clairwood, inland from the Bluff’s western ridge (see Figure 2.1).11

Figure 2.1 The Bluff’s racially mixed northern inner ridge in 1963. This photograph was taken at the time of Group Areas Act removals. A strip of Indian houses can be seen on farmland to the north of the railway track. The recently removed Zanzibari community lived just east of the railway tracks. At the bottom centre of the picture is the new Grosvenor Park Boys’ School built for whites.

The Bluff’s coming of age as a white suburb was therefore grounded in twin forces of destruction and construction: the removal of black residents and the building of new institutions for whites, including schools. In 1965, the Bluff Ratepayer commented after the opening of two English secondary schools and a co-educational Afrikaans high school: ‘[O]ne of the very few ways in which the Bluff holds its own, or is even in advance of other areas, is in the wealth of educational facilities which we possess.’12 Secondary schooling was relatively new for working-class whites and helped cement whiteness’s association with civilisation and intelligence.

Moreover, when you needed a ‘race’ to attend a school, what could be more innocent than identifying along racial lines? At Epsom, a school in the lower Berea with a reputation for admitting children who were considered on the borderline between being white and Coloured, backlogs in classification in the early 1960s led to the ‘tragedy’ of some children having ‘no race’ and thus no clear path through schooling.13 Yet, as this example suggests, urban apartheid did not fall into place easily, and I further illuminate this point through two examples: the difference between the upper and lower parts of Berea, and the centrality of class to racial classification.

The Group Area Act’s spatial limitations: the upper and lower Berea

For Durbanites, the Berea ridge evokes an image of cool sea breezes and large family houses (Figure 2.2). However, the lower areas of the ridge, stretching from the Greyville racecourse to Umbilo’s factories, long housed poorer white as well as Indian, Coloured, and African residents.14 Some Indians, who outnumbered whites in the city, had the means to buy property on the Berea. While opposition among whites to this Indian ‘penetration’ had a long history, the 1950 Group Areas Act mandated the removal of all Indian renters and property owners in areas such as Berea.15 Also facing removals were black Africans living in municipal hostels and family accommodation close to the central business district.

Yet, in the lower Berea and CBD, a significant number of Indian businesses and residences did manage to survive apartheid removals. Over 1,300 Indian businesses, owned primarily by Muslim traders, many with ancestors from Gujarat, were located in or near Grey Street, just inland from the ‘white’ CBD.16 While this Indian business district, and the surrounding residential areas, faced constant restrictions and threats of removal, residents protested determinedly. State entities were also hesitant to raze institutions that might promote ethnic and racial identities. At nearby Greyville, a cluster of 13 black education institutions remained standing, including Orient Islamic School, Sastri College, and M. L. Sultan Technical College.17 The state’s inability to sever connections between race, class, and place had important consequences, as we shall see.

Race, class, and classification

The notion of ‘race’ that justifies so much violence in the world is, in historical terms, a mutable one: at various times it has been used to refer to root, pedigree, culture, ethnicity, nation, and phenotypic differences.18 Thus, convinced of their own superiority, nineteenth-century English speakers could deride the backwardness of the Boer/Afrikaner ‘race’.19

In the apartheid period, however, race became the basis of a massive system of classification and segregation. What were some of the principles by which ‘race’ attained authority so soon after the horrors of Nazi eugenics? To recognise a person as white, Natal’s educational ordinance had historically used descent as a criterion (i.e. purity of blood for three generations).20 In contrast, the 1950 Population Registration Act called on a person’s ‘habits, education and speech and deportment and demeanour’.21 This ‘common-sense’ definition sped up the classification process and allayed fears among white families that they might have black ancestors.22

In practice, classifiers combined phenotypic traits such as skin colour, facial features, and hair texture with cultural codings of race. Social class became especially important in determining boundaries between whites and Coloureds, and between Africans and Coloureds: groups who were not always definitively categorised through visual markers. Class could be indicated by a person’s place of residence, dress, accent, and even sports played. Deborah Posel documents how one race classification board in Johannesburg noted that ‘a soccer player is native [the precursor of “African”], a rugby player is a Coloured’.23

Connecting race to culture gave racial classification a fuzziness, a lack of precision, that continued throughout apartheid and beyond, as we shall see. It made whiteness never fixed but always shot through with class in particular, and it made schools important nodes in the regulation of race. As Posel shows, white schooling communities could exclude children who looked or acted ‘Coloured’ (i.e. broadly mixed race) even if their parents were classified as ‘white’.24

At the same time, the fuzziness of race meant that a child’s schooling could be used as evidence that they should be reclassified ‘up’ the racial hierarchy. The ‘Zanzibaris’ were a group descended from freed slaves who settled on Bluff land purchased by the Grey Street Mosque Trust. When this Muslim community faced removal in the early 1960s, the Native Affairs Department first classified its members as ‘natives’. However, representatives from the Grey Street Mosque and the city’s Native Administration Department argued that the community’s children attended Indian schools, were Muslim, and should therefore live in an Indian area.25 The Zanzibaris were eventually classified as ‘Other Asiatics’ and moved to the Bayview section of the new ‘Indian’ township of Chatsworth. The Zanzibari land came to house a residence for elderly white people called ‘Peacehaven’.

White schools’ extensive powers over admissions, and therefore the racial ordering of society, need to be flagged at this point. Whereas the Pretoria government took control over African, Coloured, and Indian schooling, it left the administration of white schools to the four provinces. Natal Province oversaw 360 white schools but its jurisdiction stretched more than 500 kilometres, making it obligatory that certain powers be devolved to individual schools.26 Thus, South Africa never developed city-based local education authorities that administered admissions like those formed in Britain.

With power over who they admitted, schools were in a position to make life-changing judgements about an applicant’s race and class. Because upper-class schools were generally located some distance from black and working-class white residents, one easy way for schools to exclude questionable applicants was to insist that they attend their own local schools. A former teacher from a top Berea boys’ school described an informal system of zoning whereby the school used Mansfield, a working-class white school located down the Berea ridge close to the black education complex, as a buffer to keep out undesirable students who did not live close to the elite school. ‘Every day we used to thank the Lord for Mansfield,’ he told me.

This former teacher, now in his seventies, also suggested that admissions processes could utilise pseudoscientific measures of race, such as the infamous ‘pencil test’ that assessed a person’s race from their hair texture:

You see, Mansfield, in the days of apartheid or what have you, a lot of the kids that went there were Coloured. They wouldn’t have them here [the prestigious Berea school]. I mean one of the tests they did – I mean it was bloody Germany all over again. The kid would apply here and the Head would say, yes OK, and then he wasn’t sure if he might be Coloured or something. Because if he was Coloured, well, he could have slightly frizzy hair, although if he had more predominantly the white genes then he probably had smooth hair. But one of the tricks is they … put a pencil in the guy’s hair – and if it doesn’t fall out then you don’t accept him. I mean really, you know. And, of course, the Coloureds, a lot of them did go into Mansfield or what have you.

As a white-classified school, it seems very unlikely that Mansfield believed it was admitting ‘a lot of’ Coloureds. One former Mansfield student whom I asked about this comment said that perhaps the former teacher meant Portuguese students. While the extent that the pencil test was used in white schools is hard to determine, the practice follows logically from the fact that white schools administered admissions and excluded children who were not thought to be white.

What is clear is that Mansfield’s reputation for admitting working-class whites and perhaps even Coloureds evoked ideas that ‘poor whites’ existed ‘on the borders of respectability, of colour, of whiteness’.27 One University of Natal report written in the 1970s also described Mansfield School (along with Greyville racecourse and the Botanic Gardens) as a ‘buffer’ that divided white residential areas from the predominantly Indian educational complex.28 Moreover, the sentiment that working-class whites needed racial upliftment is evidenced in a newspaper article that celebrated the ‘missionary work’ of teachers leaving Durban High School to head lesser-status white schools.29 Missionaries were, of course, the quintessential bringers of civilisation to black society.

If a person’s social class affected their racial classification in the early apartheid period, by the late 1960s this was changing. A major success of the apartheid state was its institutionalisation of race in identity cards and segregated ‘group areas’. Children mostly attended their local school in racially zoned suburbs and racial classification itself shifted to being a ‘purely administrative and bureaucratic matter’ when children’s race followed that of their parents.30 As Keith Breckenridge writes, this system of racial descent was ‘invented’ in that it rested on the arbitrary foundations of mass classification in the 1950s and 1960s (i.e. through ‘common-sense’ definitions).31

A second factor stabilising racial identities was rising white living standards. In the 1960s, the wage differential between skilled (white) and unskilled (black) work was four to six times what it was in Europe and the United States.32 If even working-class children attended affluent white schools and had their clothes washed by a black maid, how could they be seen as somehow black? Indeed, as race separation intensified, it is noticeable that derogatory terms directed towards working-class whites such as ‘Scumbilo’ (addressed to those from the working-class Umbilo area) and the ‘rough and tough Bluff’ did not explicitly evoke race. At the same time, residues of past meanings lingered. One white Durbanite told me that poor whites could continue to be referred to as ‘white Kaffirs’ (Kaffir is a highly derogatory racist term used for black Africans).33

Below, I continue to highlight differences in whiteness and among white-classified people by contrasting elite ‘traditional’ schools located on the Berea with more working-class schools located in south Durban, specifically the Bluff.

Berea elites and traditional schools

After the British proclaimed Natal a colony in 1843, the Berea ridge became a favoured place for settlement (Figure 2.3). When British writer Anthony Trollope visited Durban in 1877, a city then of around 4,000, he noted that the views from the Berea ridge ‘would be very precious to many an opulent suburb in England’.34 As a settler community whose ideas of whiteness were always in the process of being made, great attention was placed on decorum; as Trollope notes, ‘a colonial town is ashamed of itself if it has not its garden, its hospital, its public library, and its two or three churches, even in its early days’.35

Durban’s population swelled in the twentieth century, and a house’s height on the Berea slopes became a good predictor of its price.36 Anthropologist Eleanor Preston-Whyte described the upper parts of Berea’s Morningside area in the early 1960s as ‘remarkably homogenous’: overwhelmingly white and English speaking, with men working as professionals and in businesses – and their wives occupying their time with ‘[b]ridge, sport and charity work’.37 The term ‘Berea style’ is testimony to how Berea became synonymous with cultural prestige. The style signalled elegance and class, such as its Edwardian white iron balconies that afforded residents a cool sea breeze to offset the humid subtropical climate.

All of Durban’s early prestigious schools were located on the Berea ridge. Durban High School, which opened in the city centre in 1866, relocated to the Musgrave suburb in 1895. Durban Girls’ High School opened in 1882, Durban Preparatory High School was set up in 1910 to channel students into Durban High School, Glenwood High School moved to Berea in 1934, and the private Durban Girls’ College opened in 1877. These establishments had close ties to Natal’s earliest schools built in the colonial capital of Pietermaritzburg and its nearby Midlands region.

Further afield, in the older Cape colony, elite English schools were built from the 1840s. In Johannesburg, a city developed only after the discovery of gold in 1886, imperial leader Lord Milner established so-called ‘Milner schools’ to anglicise this Afrikaner heartland.

So influential were South Africa’s top schools, including those on the Berea, that it was said in 1993 that only 23 ‘historic’ white schools – overwhelmingly English-medium – produced ‘the lion’s share of our political and social leadership’.38 In turn, South Africa’s prestigious schools formed part of a network of elite Anglophile institutions that dotted British colonies from the Caribbean to India.

Peter Randall shows how South Africa’s elite schools modelled themselves on English private schools, with their ‘boarding, house system, prefect system, “school spirit” and compulsory games’.39 ‘Along with the model,’ writes Randall, went ‘a vision of Englishness compounded of playing the game, midnight feasts in the dormitories … and the sporting life of the English landed gentry’.40 In this hierarchical school system, prefects enjoyed considerable powers, and the practice of ‘fagging’ ensured that younger students undertook tasks for their seniors. Single-sex institutions reflected and perpetuated the view that upper-class men should be educated to lead, and women schooled to become respectable wives.

In Britain, the gulf between government and private (ironically called public) schools continues to this day. But in South Africa private and top-tier government schools shared many features. One 1974 study of ‘white South African elites’ found that seven of the country’s top 12 schools were in fact government schools, with Durban High School producing the most influential leaders in the country.41 By promoting discipline and leadership skills, including through ‘cadet’ military training, which included using live ammunition, government schools sought to produce brave gentlemen acting in the service of the British Empire.42 British troops defeated the Zulu Kingdom after a series of bloody battles in 1879 but the threat of African society continued to loom large.

Again with a legacy that continues to this day, school sports had a central place within the British private school model. Rugby, with its scrums, tackles, and teamwork, anchored a heteronormative masculinity within schools that valued discipline and physical prowess. Robert Morrell’s study of settler masculinity in colonial Natal shows that, for the Natal gentry, ‘soccer became emblematic of threatening, socially integrative forces within society. As it [the Natal gentry] forged its class identity so it took to itself the rugby code as an additional, racially exclusive, identifying feature.’43 Cricket, another British sport played in elite schools, made gentlemen – but rugby made soldiers.

Certain English schools were therefore labelled ‘traditional’ not just because they were old. They played sports together and showed fidelity to the English private school model, and their powerful old boys (and to a lesser extent old girls) became interlocked in networks of power – albeit increasingly overlapping with the growing Afrikaner business and political establishment. ‘Traditional’ or ‘great’ were not terms ever associated with schools built for children destined for the lower ranks of farming, the trades, commerce, or industry, however old the schools might have been. These included, in the lower Berea area, Clarence Primary School and Mansfield Primary School, which were opened in 1905 and 1911 respectively. South of the Berea area, Hillary Primary (built in 1889) and Seaview Primary (opened in 1904) were located near the Old Main Line, which from the late nineteenth century had connected Durban to the capital Pietermaritzburg by rail.

For a final window onto ‘traditional’ schools’ sense of superiority let us return to the 1960s and the issue of ‘zoning’: that is, admitting learners who lived locally. In the booming post-war period, admissions were largely uncontentious because children attended their local school: this was the rationale behind the expansion of schools shown in Map 2.1. In the early 1960s, however, Natal Education Department (NED) made a controversial attempt to enforce zoning in central parts of the city. A 1966 survey of central Durban’s schools found that considerable money was wasted subsidising school transport because one out of every four children travelled further than they would if they attended their nearest school.44 In the face of this challenge to their autonomy, old boys from Durban High and Glenwood High defended the schools’ favouring of the children of old boys.45 Their attitude reflected English society’s siege-like mentality when Afrikaans speakers (‘the Nats’) ascended to positions of power after the National Party’s election victory and threatened the (implicitly neutral) English school tradition.46

Eventually, the NED and Berea schools reached a compromise: a zoning system that allocated points based on children’s place of residence and on whether they had ties to the school through either their siblings’ or father’s schooling. The NED labelled zoning as ‘preferential admissions’ or ‘restrictive admissions’ and allowed schools the freedom to take out-of-area students when they were not full. As we shall see later, similar compromises over zoning – this time between the white and black middle class – were reached in the post-apartheid period.

To summarise, if a little crudely, the configuration of practices associated with whiteness became embroiled with the bricks and mortar of elite schools, with the upper-middle-class suburbs in which they were located, with the sports they played, and with the links between them and Britain. As we shall see below, the NED believed that new working-class schools should aspire to this cultural world, even if they channelled lower-class whites into industrial and trade work.

The rough and tough Bluff suburb

At the turn of the century, ‘to live on Durban’s Bluff was to be a pioneer of hardy stock. There were no amenities, no roads’.47 White residents lived on farms, in residential houses on the inner of two ridges stretching south to north from Wentworth to Fynnlands station, or at the Catholic mission. Only in 1932 did Durban city incorporate the area now called south Durban in order to facilitate the expansion of industry and white housing.

The Bluff’s first schools were primary schools, namely Van Riebeeck Park (1920) and Fynnlands (1936). While local governments supported white housing from the 1920s, it was in the post-war period that south Durban’s suburbs mushroomed, including the Bluff, Woodlands, Montclair, and Yellowwood Park (next to and a step up from Woodlands and Montclair).48 Many of south Durban’s white residents, including a large number of European immigrants, worked at local factories in Jacobs, Mobeni, and Prospecton; at one of two local oil refineries; at the airport; and at the port – the country’s busiest by far.49

However, no employer promoted the white working class more than the state-owned South African Railways and Harbours Administration. Van Tonder’s semi-autobiographical book Roepman (‘call man’) describes the modest conditions of Afrikaans speakers in the Bluff’s ‘railway camps’ linked to the port. He remembers shunters, drivers, and ticket examiners living in cramped conditions, with sometimes ‘ten people … in a three-bedroomed house’.50

At the same time, the Bluff and other parts of south Durban gained reputations not just as working-class areas but also as ‘open suburbs of Durban for young families with growing children’.51 Upper-middle-class suburbs such as Westville and Durban North grew rapidly and their excellent schools in particular decentred Berea’s image as the heartland of upper-crust society. On the Bluff, privately owned accommodation constituted a bedrock of middle-class houses that raised the area’s reputation (later, rental railway houses were themselves sold off) (Figure 2.4). A smaller number of affluent families lived on Marine Drive in houses that overlooked the Indian Ocean and shelved steeply down to the beaches. This blurring of class distinctions is why I talk of the area at times as a working-class/lower-middle-class suburb.

Schooling culture on the Bluff and in south Durban

Schools everywhere in the world are complex and varied institutions where young people’s sexual, political, and gendered identities are constantly in flux. The 1966 Grosvenor Boys’ magazine is 28 pages long and has sections dedicated to poetry, a young Christian association, science club, a speech and drama festival, and debating, as well as numerous pages devoted to sports. It reported that the library had 3,700 books; that the gardens were beautiful; and that students won awards for science projects.52

However, for the purposes of this book’s themes, let us return to the Bluff’s position in the country’s schooling hierarchy. New secondary schools built for working-class white children conferred qualifications (in Weber’s words, ‘educational patents’) that justified whites’ appointment into positions above black South Africans. The curriculum provided a view of white society as superior. ‘Cadet’ training, which increasingly fell under the auspices of the South African Defence Force, prepared young men for compulsory military service.53

Within the logic of white schooling hierarchies, the Bluff’s English schools were presented as requiring academic and, even more importantly, cultural upliftment. Grosvenor Boys’ High’s first principal, who had taught at Berea’s Durban High School and played rugby for Natal, was seen as ‘the right man to set Grosvenor Boys’ High on its feet, especially on the rugby field’.54 As the president of the Surf Lifesaving Association of South Africa said in an address to the Bluff’s Grosvenor Boys’ School: ‘[The] “moral” training and “development of character” cannot be fully achieved without participation in sports.’55

While the city’s top schools channelled graduates into high-status work, the expectation in the 1960s was that most male Bluffites would find skilled working-class or junior professional jobs. Natal’s Director of Education chose New Forest School in Woodlands, south Durban, to discuss new practical options in the curriculum. At the end of standard 6 (grade 8), he said, all pupils would take science, practical maths, and social studies, with boys channelled into handicrafts and geometrical drawing and girls ushered into home crafts, health education, office routines, and typing.56 Philip Roberts studied at New Forest in the late 1960s and told me: ‘I would say more than half left in standard 8 those days to do a trade.’ Some established their own small plumbing, building, or other businesses.

The sense of social distance between working-class Bluffites and ‘larney’ people can been seen in the account of one resident who attended an Afrikaans school on the Bluff and recalled looking for professional work in Berea in the 1970s:

Mr Louw: When I went for my first interview, there was a kid … and he actually wore a school tie to the interview. And he said to me, ‘Where did you go to school?’ And I said, ‘Dirkie Uys,’ and he said, ‘Where is that?’

Author: Which interview was that?

Mr Louw: I wanted to sign up for articles at an auditing firm and the guy sat next to me and he said, ‘It’s an old school tie type of job.’

However, as Mr Louw’s attendance at this interview suggests, bright learners at working-class schools were not completely shut off from professional jobs. Of the 1965 matriculants at the Bluff’s Grosvenor High, 11 planned to attend university out of a starting cohort of around 150.57 Within the walls of white schools, differentiation took place by means of separate streams or tracks, sometimes organised using IQ tests. The introduction in the 1960s of ordinary-level exams (separated from advanced-level) was a deliberate strategy to give less academic students a way to stay longer at school (after 1973 these became standard and higher grades).58

Philip Roberts, the former Woodlands schoolboy quoted above, was in the school’s top stream. After he passed his matriculation exam, he found a job as a cashier in a bank and then worked his way up to become a bank manager. The white schooling system also allowed the top-tracked students to transfer into more prestigious schools with stronger academic reputations. One former student of south Durban’s New Forest School noted that some of the top students of the 8A class would transfer to Berea’s Durban High School and Glenwood, where they would study standards 9 and 10 (grades 11 and 12). The movement of a pupil did not seem to be seen, as it later would, as poaching, but rather as a sort of endorsement of the quality of the lesser-ranked school.

Working-class sports

If rugby was thought to have unmatched potential to uplift white boys, working-class communities carved out a distinct sporting counterculture. The Natal Education Department discouraged soccer in white schools especially in the 1950s and 1960s, when many schools were ‘finding their feet’; indeed, a soccer association for high schools was only established in 1986.59 However, learners at working-class schools often preferred soccer to rugby, playing the former after school and at weekends. Mr Morris, a former professional soccer player who studied at an English-medium south Durban school, told me: ‘Rugby was very dominant in our schools in those days and the principals used to in fact try to shun us away from soccer, so much so that if you were caught trying to go to soccer when you should have been playing school rugby, you would get into trouble. I mean serious trouble.’

Another male former south Durban student, who wore a Liverpool FC shirt when we met, explained how soccer was promoted at local club level, rather than under the disapproving authority of schools. This soccer culture, and its sense of being a counterculture – including through racially mixed soccer teams – is the subject of the film Soccer: south of the Umbilo (2010), written and directed by John Barker, the son of former national soccer team coach Clive Barker (the Umbilo River marks the beginning of south Durban).60 The film shows how the south Durban region produced both Barker and Gordon Igesund (national team coach from 1994 to 1997 and 2012 to 2014 respectively).

I gained further insights one day when I was invited by an organiser to a reunion at a sports club in Montclair, just inland from the Bluff. Around a hundred men, most of whom had known one another since the 1960s, stood chatting with beers in hand. A few wives sat unobtrusively at one side of the hall. The men I chatted with recalled their pride in the working-class culture of this area, some contrasting it to the ‘larney’ central parts of town. One man in his sixties told me: ‘We didn’t talk about university in our house … it was “Go and earn a wage, son.”’

After a lot of beer had been consumed, the evening climaxed with a boisterous quiz about old soccer moments in south Durban – passionate descriptions of famous players, tackles, and goals scored and saved – followed by the old soccer team posing for a group photograph. I left the reception with my own Polaroid photograph, given to me on the insistence of a man with whom I had talked and who posed next to me for the picture. We chatted in part about similarities between South Africa and the UK; I had played club soccer (football, as we called it) while attending school in England in the 1970s and 1980s, whereas rugby union was mainly played at private schools. At the gathering, I didn’t see any black former soccer players in attendance, nor Afrikaans speakers – the latter, as we shall see below, advanced largely by circumventing rather than challenging the power of English speakers.

The advancement of Afrikaans speakers

In Durban in the 1950s, only 15 per cent of whites were Afrikaans speakers. Nationally, in contrast, 58 per cent of whites spoke Afrikaans as a home language, many concentrated in the Orange Free State and Transvaal provinces, and the western parts of the Cape.61 The particular dependence of Durban’s Afrikaans speakers on railway work meant that they tended to be concentrated geographically near railway infrastructure, namely in the Bluff, Seaview, Hilary, Bellair, and Queensburgh.

The upward mobility of Afrikaans speakers in South Africa is a remarkable story of ethno-national advancement. The 1910 Union of South Africa established English and Dutch as the two official languages (Afrikaans substituting for Dutch in 1914), but English remained dominant in spheres of power.62 Although some Dutch/Afrikaans speakers were affluent farmers and professionals, thousands of ‘poor whites’ moved from rural areas to cities ill equipped with skills or capital. In 1918, a group of intellectuals founded the Broederbond, a secret cultural organisation that came to play a central role in Afrikaner nationalism and eventually in implementing apartheid.63 Afrikaner nationalists evoked past injustices, notably the British concentration camps in the Anglo-Boer War, and erased awkward truths to strengthen their unity. These included Afrikaans’ roots as a creolised version of Dutch, first written in Arabic and spoken by slaves and other immigrants (many Muslim) and indigenous persons including Khoikhoi in the Cape (Afrikaans remains spoken more by black than by white families, including ‘Coloureds’ in the Cape).64

Afrikaans-speaking children had historically been accommodated in parallel-medium schools where English-speaking culture prevailed (parallel medium meant separate Afrikaans- and English-medium classes in the same school). One former employee described the Anglophile Natal Education Department as following a ‘deliberate policy of cultural imperialism’.65 Gathering steam from the 1930s, Afrikaner nationalists demanded separate schools, and they had their first victory in Durban when Port Natal School was opened in 1941 in south Berea. Following the National Party’s triumph in the 1948 election, this move accelerated: two Afrikaans primary schools and one secondary school were opened on the Bluff, and additional co-educational Afrikaans schools were opened in Queensburgh, Durban North, Amanzimtoti, and Pinetown.

When I visited the Bluff’s Afrikaans secondary school, built in 1961, the principal walked me down a corridor and pointed to pictures of past principals adorning the walls. He told me that all but one head had left for promotion in the education bureaucracy. A prominent picture was of the founding headmaster, Philip Nel, who was placed in charge of Indian education in 1964 and then served as the director of the white NED from 1967 to 1977.

As indicated by the zoning controversy, however, Afrikaans-speaking administrators preferred compromise to conflict in dealing with English schools that, after all, were responsible for most of the province’s educational accolades. Indeed, separate schools – along with the raising of Afrikaans’ status nationally – were successful in propelling Afrikaans speakers from blue- to white-collar and government jobs such as teaching, the police force, and the army (a Special Forces training unit occupied the northern tip of the Bluff). Around 70 per cent of high-school teachers in the 1970s graduated from Afrikaans-medium schools.66 Moreover, Mr Van Rooyen, a former teacher who matriculated from Port Natal School in 1958, described the effects of state-backed volkskapitalisme (‘people’s capitalism’), which aimed to create an Afrikaner capitalist class, as follows:67

[When I was young] there were only two [children of] professional people in the school. There was … the manager of the bank they called Volkskas and the chap in charge of the insurance company, Sanlam. Only two. The rest were working on the railways, or in the army … And eventually more and more [parents] became business people.

Although in Afrikaner folklore the English were imperialists, Grundlingh documents the Afrikaans speakers’ quick embrace of Western consumer items, including cars, in the booming 1960s.68

The rising confidence of Afrikaans speakers played out elsewhere in the cultural realm, including on rugby pitches around the country. From the early twentieth century, Afrikaans speakers came to venerate rugby for its ‘ruggedness, endurance, forcefulness and determination’.69 With the backing of both English and Afrikaans speakers, rugby became a symbol of the strength of the white settler nation and its attachment to – but also its independence from – the colonial power of Britain. Rugby prowess won respect for Afrikaans schools when some were skilled enough to play prestigious English schools, such as those in Berea, that controlled what amounted to the A league (south Durban English schools typically played in a lower-status group of schools). One teacher at Port Natal School, the first Afrikaans school in Durban, described to me the time when his school beat Durban High School, as ‘one of the highlights of my career’. On the Bluff, the much-anticipated rugby match between the local Afrikaans and English boys’ schools, dubbed the ‘Boer War’ in reference to the 1899–1902 war, represented a moment of competition as well as a shared passion. It symbolised bloody past conflicts, but also that social mobility anchored in schooling could smooth over differences among whites.

Nationally, white South Africans had every reason to unite. After police gunned down 60 people in Sharpeville in 1960, an uncertain political climate ensued. The country, a republic after 1961, became increasingly ostracised from the international community. These political tensions, along with labour shortages, did not halt the state’s implementation of the Bantu Education Act. But they did encourage state officials to see Indian and Coloured workers as providing a buffer between white and African society, and this had important educational implications, which I review briefly below.

Indian workers and schooling

Bantu Education’s core belief, considered in more detail later, is captured in the much-quoted statement by then Minister Hendrik Verwoerd (president from 1958 to 1966): ‘There is no place for him [Africans] in the European community above the level of certain forms of labour.’70 Indeed, until the 1970s, almost all schools built for black Africans were primary schools. While Africans were thought of as suited for ‘routine repetitive work’, Durban’s large Indian population were thought to be capable of filling jobs requiring ‘initiative and quick thinking’.71 Anti-Indian sentiment was particularly strong in Durban, but in a structural sense Indian workers were both ‘insiders and outsiders’ under apartheid, in Bill Freund’s words.72

After the Second World War, industry had transformed from ‘small-scale craft workshops to large-scale factory production’.73 A more stratified division of labour created a demand for semi-skilled machine operators, technicians, and supervisors. The shortage of white labour, only partly mitigated by immigration, put constant pressure on the system of racial job reservations.

This tension played out in the state’s approach to Indian schooling. In 1969, Philip Nel, a key official in Indian and white schooling, as noted above, visited an Indian school on Natal’s south coast. One student, Vishnu Padayachee, who went on to become a distinguished professor of development economics at the University of Witwatersrand, remembers Nel lambasting his teacher for spending too much time teaching science to students who wouldn’t need those skills.74 As a former principal of the Bluff’s working-class Dirkie Uys Afrikaans High School, Nel must have sensed the difficulties of maintaining race-based job reservations when academic subjects were open to non-whites.

Yet Indian communities and industrialists put great pressure on the state to invest in Indian secondary schools.75 Until the 1950s, Indian educational institutions had depended heavily on the support of local businesses, communities, and religious organisations as well as transoceanic links to India itself. Few learners progressed past primary school. However, between 1955 and 1965, the number of Indian high-school pupils, many pushed into new townships, increased from 3,024 to 13,000.76 A small university for Indians was established on Salisbury Island off the Bluff in 1961 and enrolments swelled after it moved to Westville in 1971. By this period, Indians were overwhelmingly home-language English speakers, or, as sociolinguists say, ‘Indian South African English’ speakers.77

Whereas administering the ‘Bantu’ required the expertise of anthropologists, somewhat similar educational frameworks were applied to Indian and white learners. ‘Differentiated’ secondary education, explored through visits to Europe, became a key focus of Philip Nel’s tenure in charge of both Indian and white education.78 Clairwood School for Indians was opened in 1956 and combined academic subjects with workshops for motor mechanics, woodwork, fitting and turning, plumbing, welding, panel beating, and spray painting.79 Speaking at Clairwood as the head of Indian education in 1964, Mr Nel said:

During the past two decades there has been a phenomenal expansion in secondary education in various parts of the world … pupils entering secondary schools differ in age, aptitude, ability, and physical stamina … The ideal secondary school should obviously offer a wide range of differentiated courses.80

In the workplace, however, Indian workers faced constant discrimination. Mr Reddy grew up in Cato Manor and remembers his family being removed to the new Indian township of Merebank. His father worked in a shoe factory, a common job for Indian men at this time. In his interview, he recalled the painful bias that directly affected his work path:

I worked for C. G. Smith [a chemicals company] and they had white guys coming in straight out of school and being sponsored to go to university or Technikon, etc. And I approached management to say that I would also like that benefit … I said, ‘But those guys are new and I have been here five years. They just walk in and you are able to send them, so why can’t you do that for me?’ And I was told in no uncertain terms that if I bring something up again like that I will lose my job. No. It was very blatant and they were not ashamed to say you are different … I mean I worked for nearly 37, 38 years and for all that time I have always had a white person coming in, you have been told teach him the job, and a month or so after he is in the job an announcement is made that he is my boss. It happened often and I think it’s one of the most frustrating things that I have had to deal with in my working life. And you know his shortfalls and you know his weaknesses. Yet he is your boss.

Gender, white families, and schooling

A final form of educational differentiation occurred along gender lines. Robert Morrell’s study of colonial Natal brings to life the world of old Natal families and old Durban families (who came to be known as ONFs and ODFs). He described middle-class women as having a strong sense of independence, even in the nineteenth century.81 By the mid-twentieth century, headmistress Dorothy D. E. Langley (daughter of former Durban High School principal Aubrey Langley, famed for bringing rugby to the school), told the Johannesburg High School Old Girls’ Club in 1954 that: ‘Women surely appreciate the knowledge that they can be economically secure … Without being feminists, we watch and appraise the work of women in welfare, municipal and political arenas.’82

Jobs reserved for whites created a demand for educated white women, and the number of white female matriculants tripled from 1960 to 1990.83 One government official urged students at Durban Girls’ High School to meet the shortage of white (male) labour while counselling them to not neglect their roles as mothers and wives.84 However, it remained the case even in the mid-1980s that only a small proportion of white women who passed the school leaving examination enrolled in tertiary education courses.85 Overwhelmingly, men took up elite professional, political, and business positions in South African society.86

As in the case of boys’ schools, the location (and thus status) of a girls’ school affected not only the amount of polish it gave girls as potential wives but also the type of employment into which it channelled them. Berea’s popular Durban Girls’ High School celebrated old girls moving into jobs that included commerce, teaching, and nursing, with some top students entering university.87 In contrast, at Grosvenor Girls’ School on the Bluff, girls were schooled in shorthand and typing, with many leaving school for work at age 16.88 Girls’ schools shared with boys’ schools an attention to neat school uniforms and hair, but they placed much less emphasis on the sports they played such as hockey and swimming.

In the home, black female domestic workers increasingly replaced black male workers in the post-war period.89 When servants relieved much of the drudgery of housework and childcare, white women had more time for paid work and children’s schooling. Mothers wrote most of the letters to the Natal Education Department in the 1960s requesting places for their children in boarding establishments attached to some of the best schools. Complaints about men’s indifference to their children were common in correspondence. Mrs Fuller, a mother of two living on Wentworth Road near the Wentworth railway depot on the Bluff, wrote to the department in 1963 about her concerns. Her eldest child had found work in the railways, but her youngest child, aged 15, was still at school. Her husband was pressuring the youngest to find work on the railways and leave school too, but the mother wanted help in continuing the child’s education through a hostel or boarding school:90

[M]y problem though is this. My ex-husband is giving me no support whatsoever towards the boys and has failed to do so for several years. My present husband has taken a real stepfather’s attitude towards these: he makes no secret of his actual hate for them, consequently the home is a desperately unhappy place for them.

Men, in the few instances when they did write to the Department of Education, had a firmer and more demanding tone. Mr Riddle wanted to admit his son to a prestigious Berea boys’ school and gave the following reasons: ‘I would very much like him to enter a school where besides passing the usual exams they will also make a gentleman out of him.’91

However, to say that schooling was largely a female domain is not to say that men did not have close relations with their children; it is just that earning the household salary was seen as the man’s most important role. Von Tonder’s account portrays his Bluff father as a distant disciplinarian who worked long hours, with his mother being responsible for the daily care of the children.

A relevant question, itself inherently gendered, is whether young people tended to choose marriage partners on the basis of home language (English or Afrikaans) or their shared work and residential location. This is difficult to quantify, but there are many mixed Afrikaans–English couples on the Bluff. It appears to have been much more likely that a working-class English speaker would marry a working-class Afrikaans speaker (who spoke English as a second language) than someone from an upper-class Berea family. In almost all the cases I have encountered, children of mixed-language couples studied at English-medium schools.

Indeed, throughout the apartheid era and beyond, white Bluffites celebrated the suburb’s sense of community. Implicit in their identification as ‘ratepayers’ was residents’ resentment at the city’s superior treatment of more ‘larney’ areas. When a Bluff councillor advocated for his constituents, a fellow councillor asked sarcastically: ‘And where is the Bluff?’92 Environmental pollution provided another area of cooperation, Stephen Sparks showing how a white ‘civic culture’ developed to reduce pollution from South Africa’s first oil refinery, built in Wentworth in the 1950s.93

Moreover, in everyday life, leisure and shopping spaces played an important part in bringing residents together. In 1962, for instance, residents could visit the Bluff drive-in cinema to see The Gene Krupa Story about the legendary US jazz drummer.94 One resident remembered:

You had things like movies happening and local discos … Friday nights were movies in the hall … And the drive-in was the other place we used to meet. If we didn’t go to the Bluff drive-in, we went to Umbilo or Durban drive-in.

As well as soccer and rugby, the Bluff’s proximity to the beach gave it an appeal not enjoyed by other working-class suburbs. And the large winter swells that directly hit the shores gave surfers a way to distinguish themselves from the ‘town clowns’ enjoying the city’s more protected beaches.

Conclusions

The unprecedented prosperity of white South Africans in the 1960s was underpinned by a large expansion of schooling, especially at the secondary-school level. Race had fuzzy boundaries in the early apartheid period, being especially related to social class. However, segregated schooling became a key means through which ‘[t]he racial becomes the spatial. The social construction of race becomes one with the physical occupation of space. The racialized becomes the segregated, and racial meanings become inscribed upon space.’95

The privileged position of white schools should not, however, occlude differences among them. The National Party’s efforts to improve the status of Afrikaans in comparison to English stole the headlines. But elite English-speaking schools, centred on the Berea ridge, remained at the top of the schooling hierarchy in Durban – as similar schools did across South Africa, and, indeed, across the British Empire. A particular configuration of whiteness was tied to the upper Berea’s lifestyle: old boys’ networks, rugby, cricket, and businesses and professional work. Berea’s suburbs, including Musgrave, Morningside, and Essenwood, looked down literally and metaphorically on the rest of the city.

Over the harbour on the ‘rough and tough’ Bluff, differences existed among Afrikaans and English speakers but a strong sense of local white community developed. Typical work taken by Bluff school leavers was in the trades or in lower-middle-class professions. Among the English in particular, soccer was widely played after school and at the weekends.

Thus, education did not simply unfold in pre-existing racially imprinted areas; it helped to make a raced and classed city. Whiteness – or white tone – was not neatly legislated but made in mundane acts including those shaped by schooling. We will see how this planned schooling system became more marketised in the 1970s and 1980s and how working-class jobs no longer automatically guaranteed middle-class lifestyles. Ultimately, this led to quite different schooling trajectories among young white people. Before considering this, we need to explore the making of Durban’s largest township, Umlazi.